A year ago, we wrote a series of blog posts about the COVID-19 inflation shock, which showed that the pandemic together with big fiscal stimulus in many places combined to create a truly global inflation shock, forcing central banks around the world to sharply tighten monetary policy. U.S. tariffs are similar and different. For the United States—a big net importer of goods—tariffs are without doubt an inflationary impulse, but for China and the eurozone—big net exporters to the U.S.—things look quite different. Goods that prior to recent tariffs would have gone to the U.S. are now stuck in China and the eurozone, where downward pressure on prices is likely to emerge. This blog reports on preliminary survey data, which suggest that this divergence in global inflation may be starting to play out.

Diverging global inflation due to US tariffs

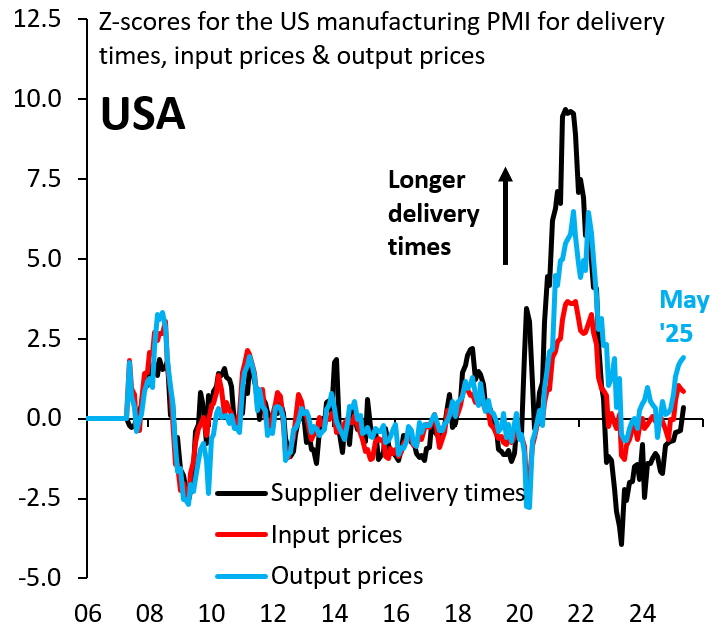

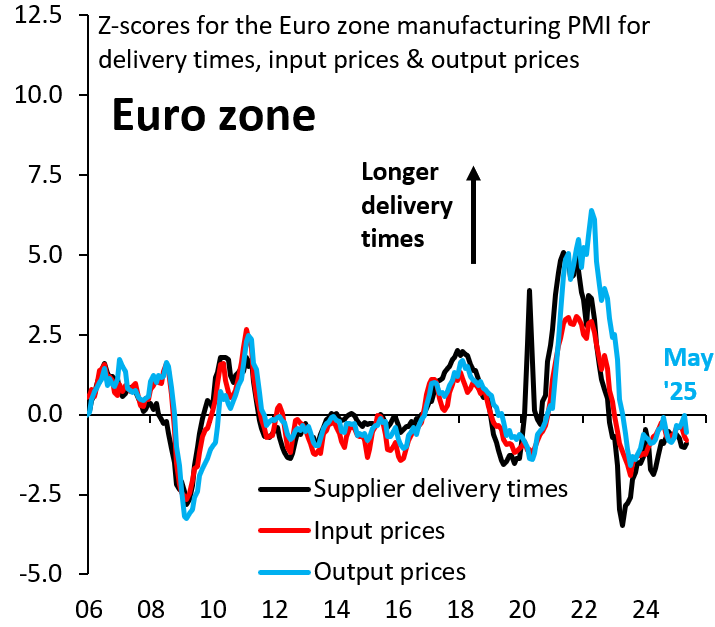

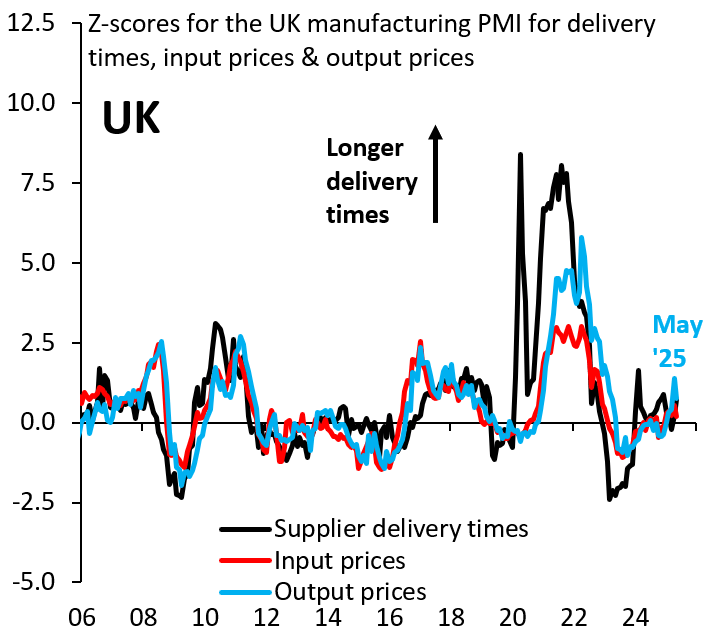

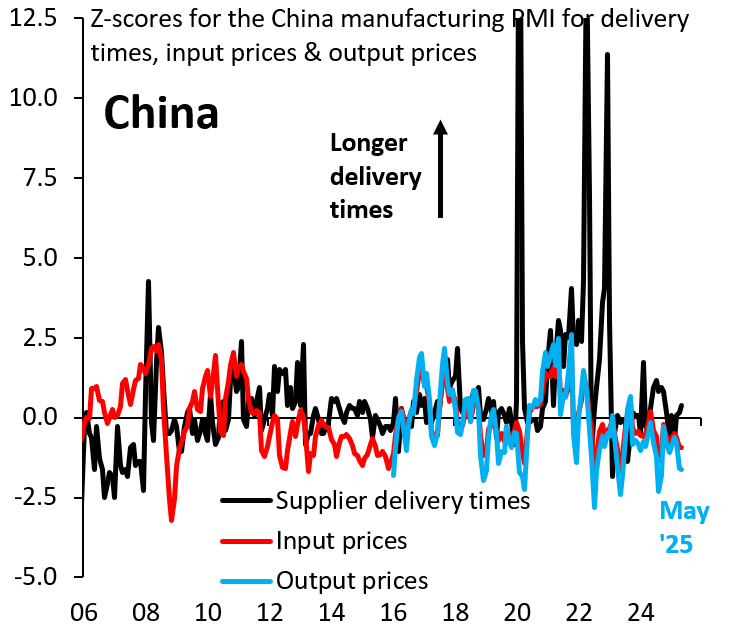

Our work on inflation a year ago relied heavily on the S&P Global purchasing manager indices (PMIs), which are monthly balance-of-opinion surveys that include data on delivery delays due to supply chain disruptions, in addition to prices companies pay to suppliers and charge customers. These data come with all the caveats of survey data, most notably that they tend to “overreact” because—in the end—they capture sentiment and not hard data. However, it’s also true that these data proved themselves during the pandemic, providing an early snapshot of the severity of COVID-era inflation.

Source: Haver Analytics

Source: Haver Analytics

Figure 1 shows supplier delivery times (black), input prices (red), and output prices (blue) from the PMI surveys for the U.S., where each of these series has been transformed into a Z-score. This means transforming the series by subtracting its historical mean and dividing the demeaned series by its historical standard deviation. As the Z-score grows, it signals increasing outlier status of data, which is certainly what happened during the pandemic. Output prices now have a Z-score of 1.9, which—while it’s nowhere near COVID-19 levels—is approaching statistical significance. Input prices are also seeing upward price pressure, but—at 0.9 standard deviations—this is still muted. Unlike during COVID-19, delivery delays are a nonissue, despite the wave of tariffs in recent months (potentially due to front-running of tariffs). Figure 2 is the same thing for the eurozone, while Figures 3 and 4 are, respectively, the same perspective for the U.K. and China. Data for the eurozone and the U.K. are inconclusive, with little sign of inflationary or deflationary pressure, not to mention delivery delays. But China’s output price Z-score is -1.6, which is approaching statistical significance. China has emerged as the main target for U.S. tariffs, so the fact that deflationary pressure looks most acute makes intuitive sense.

Source: Haver Analytics

Source: Haver Analytics

Unlike COVID-19, the U.S. tariff shock is causing inflation dynamics around the world to diverge. Tariffs are a positive inflation impulse for the U.S., but elsewhere—especially for China—this is a deflationary shock. Evidence in this direction is starting to mount in PMI survey data.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

US tariffs and global inflation

June 5, 2025