China is widely portrayed as the superior force in the ongoing trade dispute with the U. S. As someone who has worked on Russia sanctions extensively, this parallels a lot of commentary in the immediate wake of the Ukraine invasion, when “Fortress Russia” was a frequently used phrase and Putin was often portrayed as a mastermind. The reality—both for Russia and China—is quite different. As we’ve documented in a series of posts and a recent paper, Russia is uniquely vulnerable to the recent wave of sanctions on the shadow fleet. China’s export-dependent growth model is similarly vulnerable to tariffs. This post documents key aspects of China’s exports after the imposition of U.S. tariffs. Overall exports are stable, even though those to the U.S. have fallen sharply. That could reflect transshipments or it could be due to China genuinely exporting to new markets. As this post argues, either possibility amounts to a deflationary shock for China, where CPI (consumer price index) inflation is already zero.

China’s transshipment of goods around US tariffs

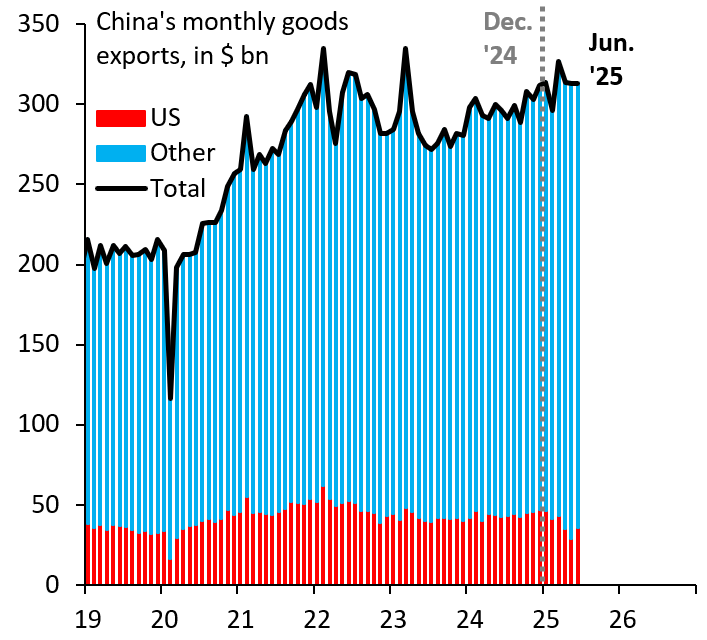

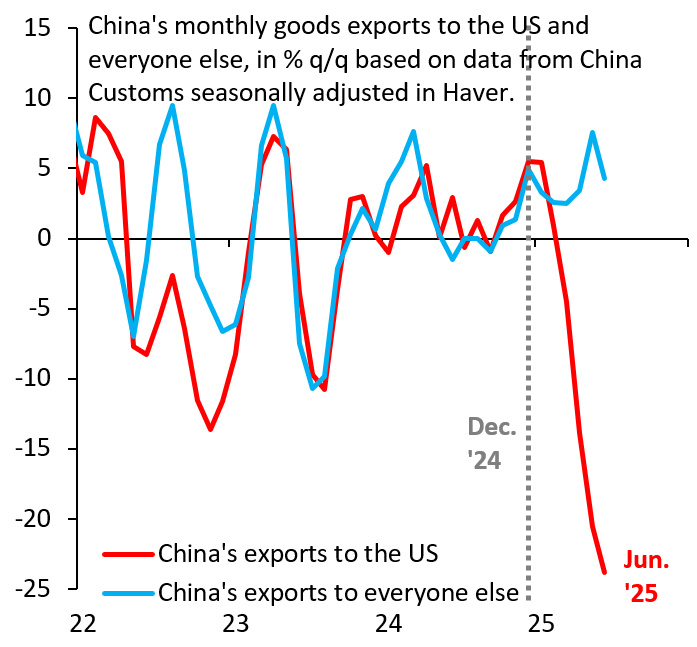

The remarkable thing about China’s overall exports is that they are up slightly so far in 2025 (Figure 1), even though direct exports to the U.S. have fallen sharply (Figure 2). The fall in direct exports to the U.S. is easy to understand. There is growing evidence that tariffs are pushing up prices for goods likely to be imported from China. Those price increases reduce demand for Chinese imports. It’s less clear why China’s exports to other countries have risen so much, essentially providing a full offset.

Source: Haver Analytics

Source: Haver Analytics

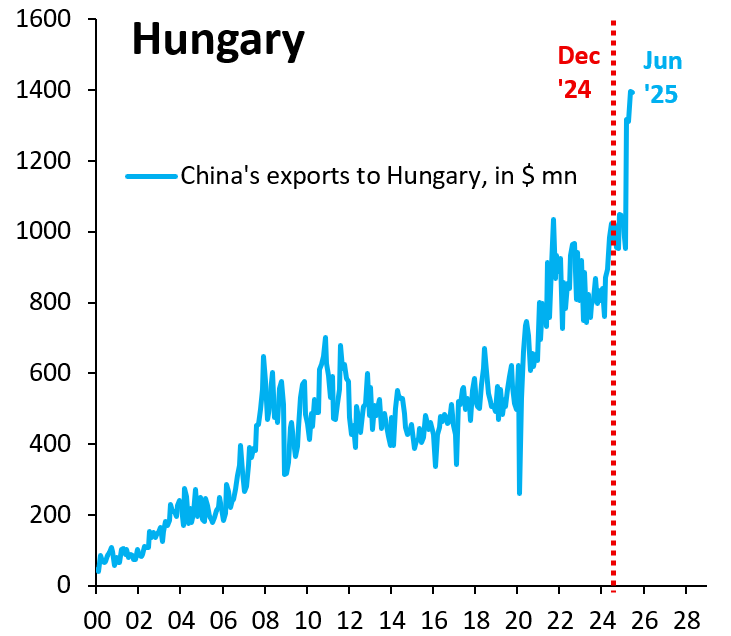

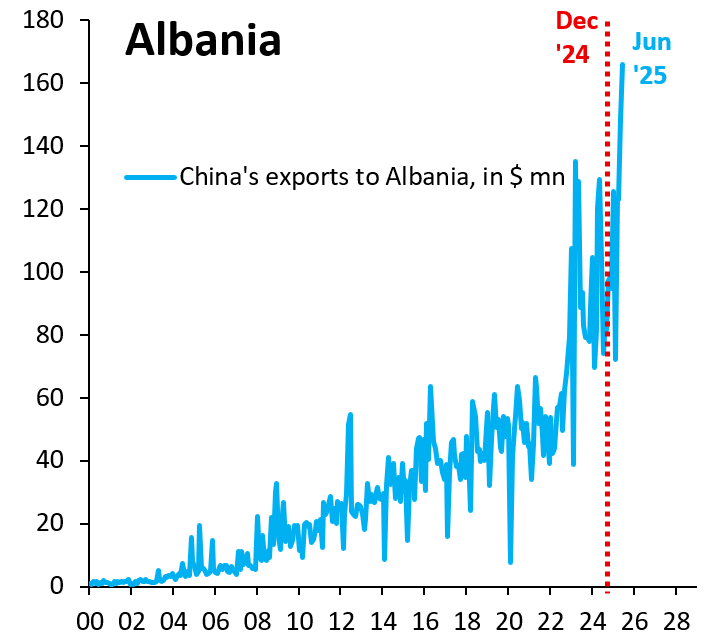

There are two explanations for why China’s exports to countries other than the U.S. have risen. The first is that China is using countries like Thailand and Vietnam (among many) to transship goods to the U.S. I documented evidence to this effect in a recent post. The second is that China is genuinely exporting to new markets. Today’s just-in-time delivery chains are extremely lean, meaning that there is relatively little warehousing capacity. As a result, it would stand to reason that China may be selling goods that otherwise would have gone to the U.S. in new markets. There is plenty of evidence in this regard. Chinese exports to a wide array of countries have risen sharply, a rise that’s coincided with the imposition of U.S. tariffs. Figure 3 shows the example of Hungary and Figure 4 shows Albania, just two of many countries where this is happening. It is impossible to tell if these are transshipments or genuine exports to these countries, but—as far as the inflationary impulse to China’s exporters—that distinction does not matter.

Source: Haver Analytics

Source: Haver Analytics

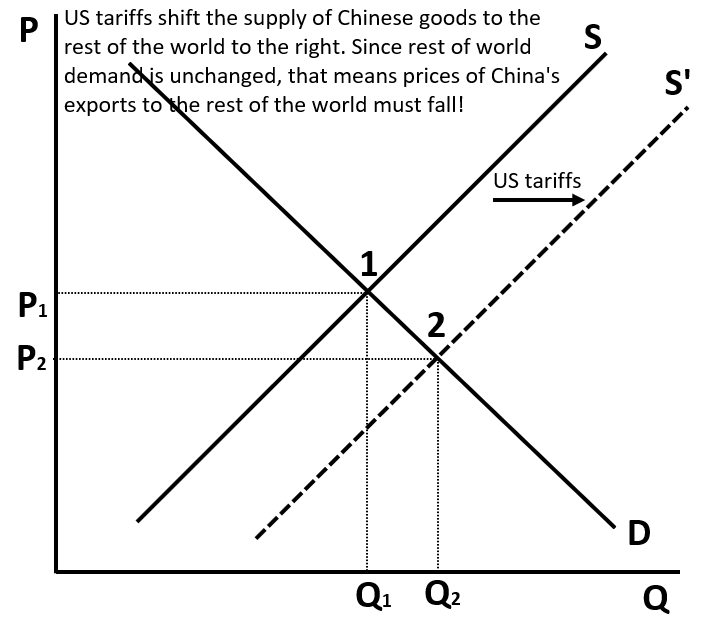

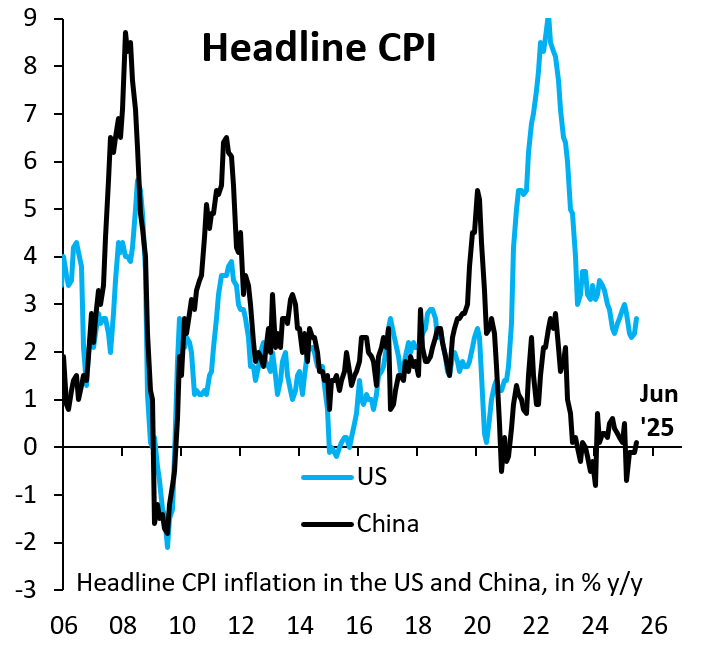

It should be obvious why transshipments are a deflationary impulse. Routing goods to the U.S. via third countries is more costly than shipping them directly. This depresses margins and profitability, which is deflationary for China. Exports to new markets are similarly deflationary. A rise in exports due to U.S. tariffs amounts to a shift down and to the right of China’s supply curve of goods to the rest of the world (Figure 5). Since the rest of the world did not ask for this influx of goods, this amounts to a move down the demand curve (there is no shift up and to the right of the demand curve like there would be in the event of fiscal stimulus). China has to lower prices to generate demand for its goods. In either case, there is a deflationary impulse to its economy. This is significant because headline inflation is already zero (Figure 6). It will take very little to push China into outright deflation.

Source: Author’s calculations

Source: Haver Analytics

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

US tariffs and deflation in China

July 24, 2025