In the 20 years following the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, successive American presidents have embraced the use of armed Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV), or drones, to carry out strikes against terrorists with little public scrutiny. George W. Bush pioneered their use. Barack Obama institutionalized and normalized the weapon, while Donald Trump continued to rely on it. And with the withdrawal from Afghanistan, Joe Biden is all but certain to maintain the status quo and continue the use of drones to meet his commitment to prevent terrorist attacks against the United States. The most visible signal that Biden will continue to rely on drones relates to a tragic error. On Aug. 29, the Biden administration authorized a drone strike in response to an attack in Afghanistan by the Islamic State’s regional affiliate that killed 13 U.S. military personnel. Instead of killing the suspected attackers, the strike killed ten civilians, including several children.

This tragedy has renewed the debate on drone warfare, but also illustrates the unique challenges facing the Biden administration in its continued reliance on drones, even after the U.S. withdrawal. While the strike raised a familiar set of moral, ethical, and legal questions associated with American drone warfare, it also reflects a new set of challenges in what has been dubbed an “over-the-horizon” strategy. This relies on what one analyst describes as “cooperation with local partners and selective interventions of air power, U.S. special operations forces, and intelligence, economic, and political support from regional bases outside of Afghanistan for the narrow purpose of counterterrorism.” This strategy assumes, however, that the U.S. has the requisite technical infrastructure and intelligence sharing agreements in place to enable the targeting of high-value terrorists in Afghanistan.

Fighting over-the-horizon

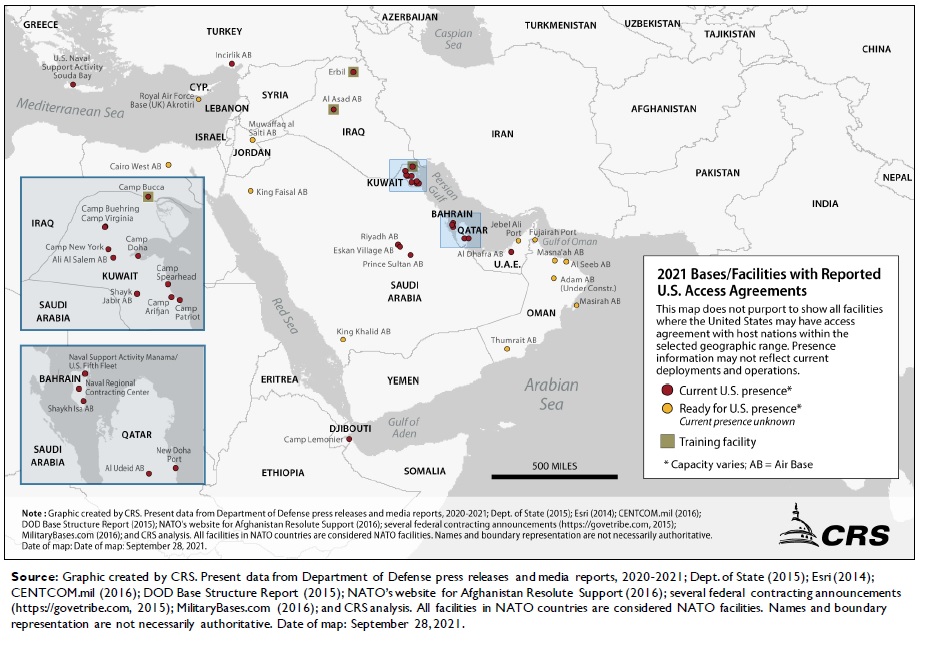

The OTH strategy has intuitive appeal. It allows the United States to conserve resources while deputizing others to do most of the dirty work involved with hunting terrorists. The recent drone strike in Afghanistan, however, reveals the false promise of OTH operations as neither an effective nor easy tool of warfare. Over-the-horizon implies something relational, namely that the United States still needs bases somewhere. These seemingly easy drone strikes require an elaborate array of bases from which to launch, recover, refit, and extend the loitering potential of armed drones; synchronize intelligence to identify targets; and manage cooperation with allies and partners, especially to corroborate intelligence, which is decisive in targeting high-value terrorists.

Yet this extensive infrastructure is out of sight and often out of mind. There is a tendency to define drone warfare in terms of the platform rather than the systems required to carry out drones strikes. It is tempting, for example, to focus entirely on the MQ-9 Reaper, which is the world’s most advanced armed drone and is used prolifically by the United States, rather than the pilots, bases, and logistics and maintenance personnel that make their use possible. Such “drone essentialism” promotes what the scholar Hugh Gusterson calls a narrow focus on “the agentic capacity of drones” and comes with a key tradeoff. It encourages people to focus more on what armed drones do, namely the targeted killing of terrorists, as opposed to how they do it. Mapping the requirements of drone warfare suggests that the use of strikes for an OTH strategy in Afghanistan is more complicated than most observers realize.

The limits of OTH drone strikes in Afghanistan

Though U.S. forces have withdrawn from Afghanistan, there is good reason to believe the United States will continue military operations there. Contrary to Biden’s assertion that al-Qaida is “gone” from Afghanistan, General Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, recently argued that there “is a real possibility” that both al-Qaida and the Islamic State may reconstitute in Afghanistan by the spring of 2022. Spokesmen from al-Qaida said their group’s war against the United States continues until “they are expelled from the rest of the Islamic world,” and an Islamic State spokesman in Afghanistan said that “the soldiers of the caliphate will continue to fight them until God decrees a matter that has been done.” Without a base in Afghanistan or military installations in Central and South Asia, the U.S. will likely have little choice but to conduct OTH operations against terrorists in Afghanistan.

Armed drones are the tip of the iceberg in terms of the broader technological and analytical infrastructure on which they rely. This infrastructure consists of a globe-spanning intelligence collection and analysis architecture that one U.S. Air Force expert refers to as a “system of systems.” It takes more than 200 personnel to operate an armed drone for a 24-hour period, and approximately 60 of these individuals are deployed within a theater of operations or to bases within close proximity to a conflict.

Some personnel launch and recover drones, especially the MQ-9 Reaper, through a sophisticated software that now increasingly enables automatic takeoff and landing. Known as the “Automatic Takeoff and Landing Capability,” this technology allows even non-qualified launch and recovery pilots to deploy and redeploy drones on unimproved airfields with the aid of satellite control. Pilots use satellite imagery to generate reference points for the automated landing procedure. Other personnel maintain and rearm drones. Still other personnel provide intelligence to pilots enabling situational awareness of the enemy situation given shifts in a clandestine network’s composition, disposition, and intent. Intelligence is fed into a Multi-Spectral Targeting System. This is a powerful graphic user interface for the MQ-9 Reaper that consists of multiple visual sensors that also allows pilots to fix targets through a laser designation application that guides a Hellfire missile onto a target. These functions are the “human element” of drone warfare, which can take a psychological toll on the whole community that supports strikes, both because of what military personnel experience as well as the “round-the-clock” schedules they keep.

Beyond the hidden human toll, the OTH strategy assumes that without regional bases across Central and South Asia, the United States will still be able to conduct drone strikes against terrorists in Afghanistan. Any such strikes would be launched from armed drones staged at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar. By launching from Qatar, U.S. armed drones will consume large amounts of their fuel getting to Afghanistan, and such high fuel consumption may require armed drones to be recovered in places closer to Afghanistan. Without a base in Afghanistan or anywhere in the region to recover drones short on fuel, it is unclear how the United States can execute OTH strikes. One of the main advantages of armed drones is that they have “long legs” and can loiter over targets for long periods of time. As transit times increase, however, U.S. drones will have less time to collect intelligence, which increases the likelihood of errant strikes. Indeed, in reflecting on the strike in late Aug., General Kenneth McKenzie, commander of U.S. Central Command, acknowledged that “[w]e did not have the luxury to develop pattern of life.”

The withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan will also mean more limited human intelligence, which provides perhaps the most important leads on the whereabouts of senior terrorist officials. The U.S. military’s initial assessment of the botched strike in late Aug. in Kabul shows just how much intelligence is required to enable drone warfare, suggesting greater challenges for OTH operations with little to no intelligence collection capabilities on the ground. Prior to the strike, U.S. intelligence analysts spent 36-hours synthesizing 60 different reports implying an imminent attack by the Islamic State against U.S. forces. According to the military, sensitive reporting, possibly signals intelligence, provided the initial narrative about the intentions and whereabouts of the suspected attack facilitator at a compound in Kabul. Using drones to observe that person of interest’s behavior over an eight-hour period appeared to confirm the initial hunches. The observation of a white Toyota Corolla at the compound proved a key piece of information, as multiple reports suggested that the facilitator would use this type of vehicle to enable the attack. Although this is a popular car in Afghanistan, the vehicle’s presence at the compound seemed to confirm the veracity of sensitive reporting leading to the tragic strike.

This phenomenon, which is referred to as “confirmation bias,” is often the result of an over-reliance on one source of intelligence at the expense of integrating multiple channels of information. The most effective drone strikes—those that kill the target while minimizing collateral damage—generally combine human and signals intelligence. The OTH strategy will likely force a greater reliance on signals intelligence given the lack of human intelligence, which risks unintended consequences. Most of the United States’ human intelligence collection capabilities left the country. So have those of its allies, which is another important source of intelligence for drones strikes. In 2017, for instance, the U.S. military coordinated with the French military to enable operations against French and Algerian foreign fighters who travelled from Syria to join the Islamic State in Afghanistan. The U.S. no longer has such partner capacity in the region for anything similar in Afghanistan in the future.

The future of OTH drone strikes

Since the botched strike in Afghanistan, the Biden administration has already carried out another, far less fraught drone strike, targeting a senior al-Qaida official in Syria. The close succession of strikes, one in Afghanistan and the other in the Middle East, is suggestive. It implies that the Biden administration may privilege armed drones as a “weapon of choice” for U.S. counterterrorism efforts around the globe. But before quickly embracing an OTH strategy, the United States should consider at least two policy options to mitigate the strategy’s inherent but often less visible risks.

If the United States is going to pursue these OTH counterterrorism strikes in Afghanistan, it must secure more proximate bases. Presently, logistics is the Achilles’ heel for OTH operations. Negotiating basing rights would enable the United States to generate the intelligence required to maintain a higher “near certainty” standard of no civilian casualties prior to conducting drone strikes. McKenzie recently said that U.S. strikes will in the future be carried out “under a higher standard” and described that shift as “a policy matter, not a purely military matter.” But it is difficult to see how such strikes could be carried out under a higher standard of certainty without regional bases that afford greater intelligence collection opportunities and responsiveness.

To overcome the logistical limitations imposed by flying drones to Afghanistan from Qatar, the United States has taken the unusual step of approaching Russia to discuss use of their bases in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. This approach, of course, is not without challenges. The U.S. Congress recently passed a law that prohibits bilateral military cooperation with Russian forces unless Russia redeploys troops from Ukraine. At the same time, Russia is reportedly adamantly opposed to a U.S. military presence in Central Asia, which it has historically considered its sphere of influence. Given Russia’s public opposition, the United States will need to work directly with Central Asian Leaders on a number of fronts. The U.S. can seek bilateral arrangements, for instance, that would secure access to bases from which to launch drones into Afghanistan and recover them after strikes.

Additionally, the United States should lead a regionally coordinated counterterrorism strategy to encourage its allies and partners to assume more costs for security within Afghanistan. Both France and India, for example, have a vested interest in securing Afghanistan based on the threat posed by especially the Islamic State’s regional redoubt to their citizens. France has purchased numerous MQ-9 Reapers from the U.S. and also benefited from transactional intelligence sharing with America to eliminate terrorists affiliated with al-Qaida and the Islamic State in Mali. While India has already leased two MQ-9B SeaGuardian drones from the U.S. to enhance its maritime surveillance in the India Ocean, it is finalizing a $3 billion purchase for 30 more MQ-9B systems that could conduct air strikes. If completed, the purchase would represent the first time a country outside of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization has received armed drones from the U.S. These initiatives set the conditions for more equitable cooperation in managing terrorists in Afghanistan, which are now actively consolidating and reorganizing to attack America’s interests in the region if not at home.

Without taking these measures, the U.S. embrace of an OTH strategy—no matter how advanced the technology is—will almost inevitably incur civilian casualties like those resulting from the ill-fated strike in Kabul.

Sarah Kreps is the John L. Wetherill Professor of Government at Cornell University and the director of the Cornell Tech Policy Lab.

Paul Lushenko is a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army, a doctoral student at Cornell University, and co-editor of the forthcoming volume, Drones and Global Order: Implications of Remote Warfare for International Society.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or Government.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

US faces immense obstacles to continued drone war in Afghanistan

October 19, 2021