Below is Chapter 3 of the 2026 Foresight Africa report, which brings together leading scholars and practitioners to illuminate how Africa can navigate the challenges of 2026 and chart a path toward inclusive, resilient, and self-determined growth.

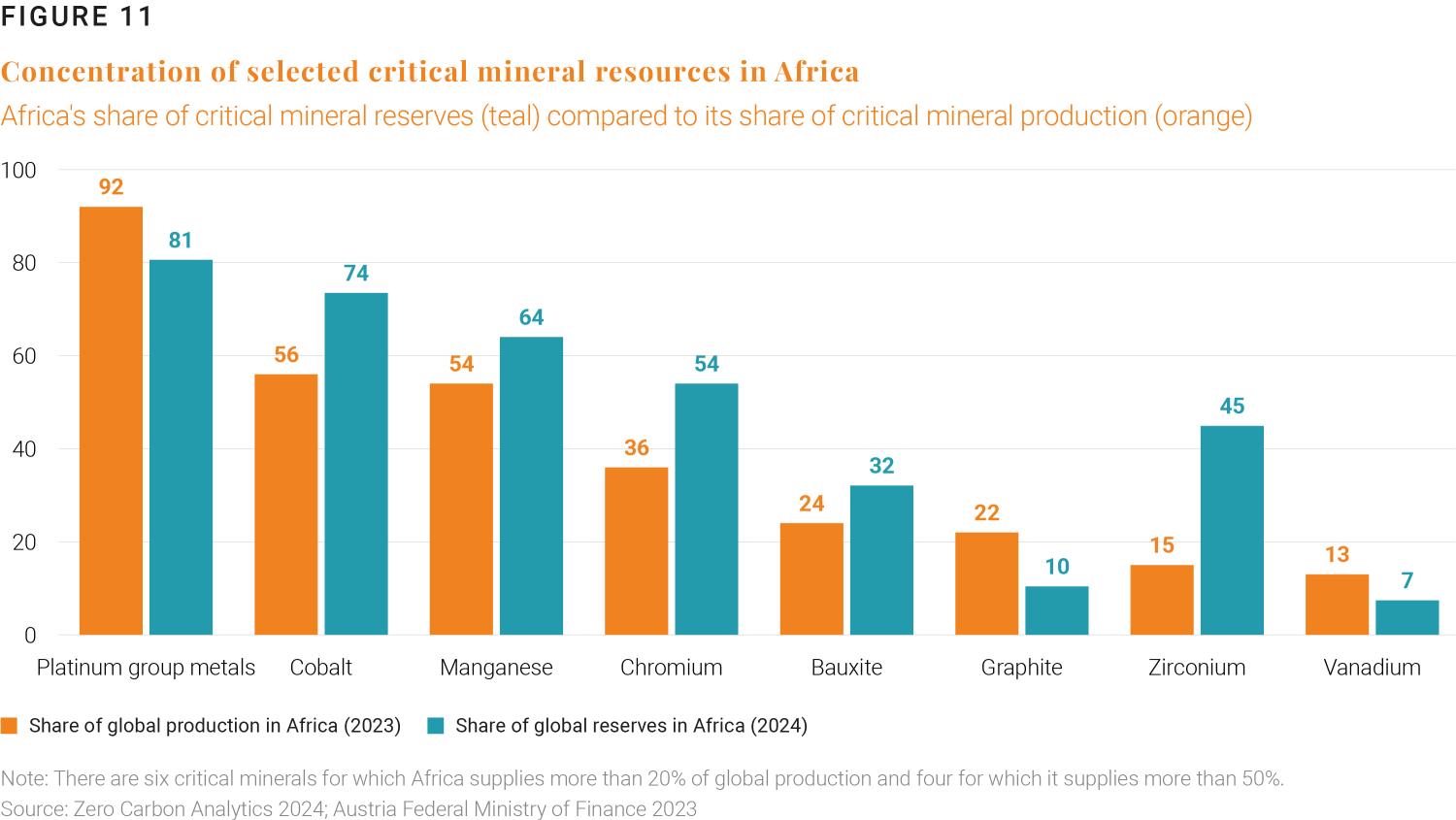

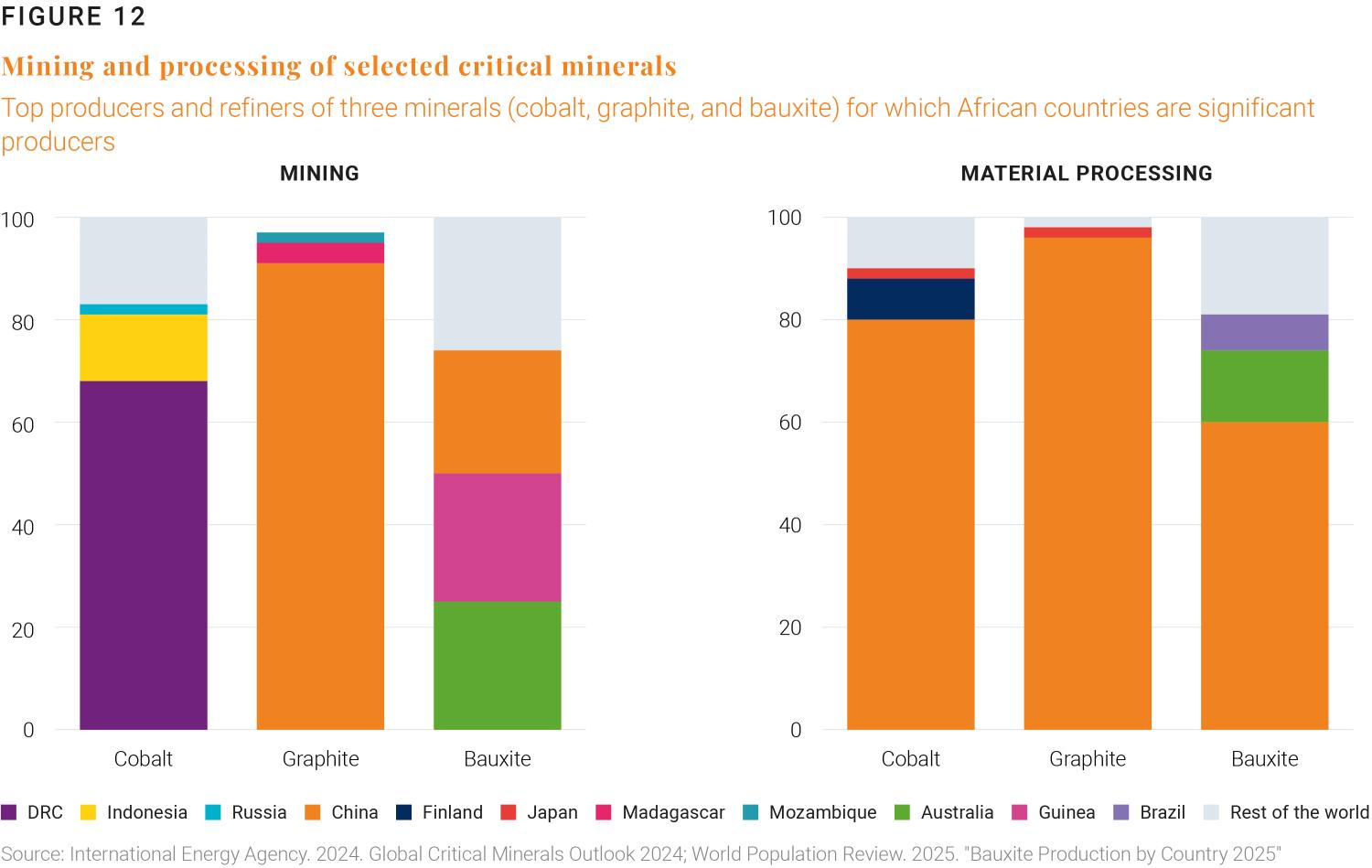

The race for critical minerals is on.1 The demand is high and growing: By 2040, 4.5 times as much lithium and 2.3 times as much graphite will be needed.2 But mining and processing are highly concentrated: For most critical minerals, the top three global producers account for more than 50% of output.3 Of these top producers, China is responsible for 60% of global mining output and 91% of global production such as separation and refining.4 The world depends on China’s processed minerals for a wide range of industries at the core of the global economy and technology, such as magnets used in cars, data centers, defense technologies, industrial motors, and other applications in energy and AI.5 However, the lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic and the changing geopolitical winds call for greater supply chain resilience and a more diverse set of trusted suppliers.

In Africa, extraction plays a large role (accounting for 76% of global manganese and 69% of cobalt) but refining is much more limited (9% for copper, <5% for other key minerals).6 Despite accounting for less than 1% of the global value from clean energy technologies and components manufacturing,7 Africa is well-positioned to become one of these trusted partners to the world—but the continent needs to jump on the opportunity quickly.

However, Africa should not rush blindly into the critical minerals race. The continent can draw on its many lessons and experiences to make this opportunity work for its citizens, the environment, and future generations. For this essay, rather than focus on the actions needed to make the mining of critical minerals a success (these are covered in detail in our recent paper “Leveraging US-Africa critical mineral opportunities”)8, we instead focus on the opportunities the region has to leverage this juncture to create more high-quality jobs, develop a vibrant ecosystem of businesses in the mining value chain, and close the infrastructure gap to serve the mining sector and beyond.

Critical minerals as a catalyst for prosperity

Infrastructure services can be designed for and beyond the mine simultaneously. Mining requires lots of energy and well-functioning connectivity infrastructure from mines to ports. For example, the rail and port financing needs for the Simandou mine in Guinea are estimated to be at least $6 billion,9 while the Lobito corridor for exporting minerals from the DRC may require up to $2.4 billion for completion.10 The Program for Infrastructure Development in Africa’s (PIDA’s) regional infrastructure projects (many of which are related to exports of minerals) are estimated to cost $360 billion by 2040.11 While the need is great, these types of investment are extremely attractive to the private sector and can be transformational for the countries they inhabit.

However, a narrow view of these infrastructure projects, designed solely for mining products, is expensive, unambitious, inefficient, and can undermine opportunities for economic development. Countries along the mining corridors can invest in complementary infrastructure (secondary roads, special economic and industrial zones, and urban infrastructure for cities along the corridor). These additional, complementary investments are the key to unleashing economic development along the transportation and energy corridor, unlocking new business opportunities, and creating high-quality jobs. For example, the development of the Tanger Med port in Morocco was accompanied by a supportive program to develop industrial zones which are now home to 1,200 companies, 110,00 jobs, and exports of $15 billion a year.12 The success of the port was not due only to its own development, but also to the complementary infrastructure and the enabling environment for business creation and growth.

Most jobs are outside the mine. Based on our calculations, the projected number of additional formal jobs in copper, cobalt, nickel, and lithium mines may be around 286,000 by 2040.13 Boston Consulting Group estimates the broader impacts, finding that a $1 billion investment in mining and processing can create 3,000-6,000 direct jobs, contribute $210-$280 million to GDP in steady state, increase annual incremental government revenue by $70-$100 million in steady state, and lead to $100 million spent on regional infrastructure.14 Policymakers should therefore be thinking of how to support and maximize these secondary impacts.

The way forward

African countries can leverage the expansion of critical minerals in five manifold ways.

First, local mining suppliers can be, with adequate support, an important source of employment. While many countries have local content regulations, they have not yielded the intended results due to insufficient monitoring and the insufficient ability of local suppliers to meet the specific requirements of international mining companies. Examples include Ghana, where local procurement of goods and services by mines reached $2.67 billion (a little over half of mining revenues) in 2020.15 Local suppliers face significant challenges, such as: (i) capital constraints (that can be resolved with supplier development funds like the Zimele enterprise development program in South Africa16), (ii) insufficient know-how (a barrier that can be gradually resolved through joint ventures with international suppliers, with examples in Burkina Faso17 or Tanzania18), or (iii) scale (which can be addressed by leveraging the African Continental Free Trade Agreement19).

Despite accounting for less than 1% of the global value from clean energy technologies and components manufacturing, Africa is well-positioned to become one of these trusted partners to the world—but the continent needs to jump on the opportunity quickly.

Second, African countries can gradually move up the value chain of processed metals and precursors. The African Development Bank, in its analysis of potential value chains in Africa, indicates that local investors can begin to engage in the processing of rare earth elements into concentrates and gradually move up to more complex processing steps like smelting, processing, and refining.20 If African countries could successfully do so, the IEA estimates that by 2040, the market value for minerals on the continent would increase by almost three-quarters compared to today’s $120 billion.21 To get there, commitment to upskilling workers, improving transport infrastructure, and managing political and currency risk will be critical.22 Some examples demonstrating these commitments include a plant about to enter into operation for the processing of lithium sulfate in Zimbabwe23 and the production of nickel-manganese-cobalt precursor cathode active materials in Morocco.24

Third, supporting the development of industries in special economic zones (SEZs) and cities along transportation and energy corridors serving the mines can leverage the infrastructure investments required for the export of mining products. For example, the Kigali Special Economic Zone (KSEZ) currently hosts 243 firms across several sectors and has generated over 16,000 jobs.25 The success factors of KSEZ, such as a strong institutional framework and incentives, an export orientation, reliable infrastructure services, and stable governance, should be at the core of SEZs along development corridors linked to mines.

Fourth, upgraded infrastructure must address issues of food resilience and food security. Almost 40% of all locally produced agricultural commodities in Africa are lost in transportation.26 The same transportation infrastructure that supports mining—ports, roads and railways—can also serve to reduce lead times, costs, and uncertainty in the transport of food across the continent. Considering that half the labor force in the average African country is employed in agriculture, investments in these areas also have tremendous potential for job creation.27 At the same time, opportunities for structural transformation in the export and processing of critical minerals can blunt the impact of adverse shocks in agriculture, as happened in the case of Zambia.28

Fifth, without strong coordination across government agencies, the full potential of mining cannot be achieved. In our paper, we recommend that African countries consider a single, high-level national coordinator, or “czar,” to implement “a whole-of-government approach for the critical minerals, infrastructure, energy, and value chain sectors.”29 A strong position in the global competitive landscape for critical minerals requires strong coordination across ministries and agencies (within and beyond the mining sector). A platform that seamlessly integrates project negotiations, permitting, land acquisition, and approval processes will make African nations more attractive. This czar should have the authority to engage with other countries on regional infrastructure projects and to leverage AfCFTA’s potential. The high-level national coordinator can be most effective leading an inter-ministerial commission with a clear mandate and ability to mobilize resources.

The critical minerals race is a unique opportunity to promote Africa as a reliable partner to countries that need these resources. The past mistakes of resource extraction without sustainable development, untransparent arrangements, and missed opportunities must not be repeated. The region’s political commitment, as reflected in the Africa Union’s Green Mineral Strategy,30 offers a platform for transformation. Africa must now work together to move toward implementation to reap the benefits of this unprecedented opportunity for growth and prosperity.

Related viewpoints

-

Footnotes

- This essay builds from a publication co-authored by Ede Ijjasz-Vasquez, Landry Signé, and Vera Songwe, “Leveraging US-Africa Critical Mineral Opportunities: Strategies for Success,” Brookings Institution, September 29, 2025.

- IEA, “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025,” IEA, May 21, 2025.

- IEA, “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025”

- Tae-Yoon Kim et al., “With New Export Controls on Critical Minerals, Supply Concentration Risks Become Reality – Analysis,” IEA, October 23, 2025.

- Tae-Yoon Kim et al., “With New Export Controls on Critical Minerals, Supply Concentration Risks Become Reality”

- Stepping Up the Value Chain in Africa (IEA, 2025).

- Stepping Up the Value Chain in Africa (IEA, 2025).

- Ede Ijjasz-Vasquez et al., “Leveraging US-Africa Critical Mineral Opportunities: Strategies for Success,” Brookings Institution, September 29, 2025.

- “Simandou Iron Ore Project Update,” RioTinto, December 6, 2023.

- Isabelle King, “Refining the Lobito Corridor: The Future of Cobalt in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Harvard International Review, August 22, 2024.

- Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA): First 10-Year Implementation Report, “Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA): First 10-Year Implementation Report,” 2023.

- Ahmed Eljechtimi, “Morocco’s Tanger Med Port Expects to Exceed Nominal Container Capacity,” Reuters, June 10, 2024.

- Ede Ijjasz-Vasquez et al., “Leveraging US-Africa Critical Mineral Opportunities: Strategies for Success,” Brookings Institution, September 29, 2025.

- Peter Clearkin et al., Africa Unleashed: Harnessing Africa’s Critical Mineral Opportunity (Boston Consulting Group, 2025).

- A. Atta-Quayson, “Local Procurement in the Mining Sector: Is Ghana Swimming with the Tide?,” Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy 122, no. 2 (2022): 1–13.

- “Zimele – Anglo American South Africa,” AngloAmerican, accessed November 20, 2025.

- “Perenti Awarded A$1.1bn Contract at Endeavour’s Mana Mine,” Miner Weekly, June 2, 2025.

- Daniel Brightmore, “AngloGold Ashanti Establishes BG Umoja JV in Tanzania,” Mining Digital, April 19, 2021.

- Papa Daouda Diene et al., “Triple Win: How Mining Can Benefit Africa’s Citizens, Their Environment and the Energy Transition,” Natural Resource Governance Institute, November 2, 2025.

- African Natural Resources Centre (ANRC)., Rare Earth Elements (REE) – Value Chain Analysis for Mineral Based Industrialization in Africa (African Development Bank, 2021).

- Stepping Up the Value Chain in Africa (IEA, 2025).

- Stepping Up the Value Chain in Africa (IEA, 2025).

- Obert Bore, “China Tests Zimbabwe’s Lithium Ambitions With $400 Million Huayou Cobalt Plant,” The China-Global South Project, September 25, 2025.

- Ahmed Eljechtimi, “Sino-Moroccan COBCO Begins Producing EV Battery Materials,” Africa, Reuters, June 25, 2025.

- Rwanda Development Board, Annual Report 2023: Building Resilience for Sustained Economic Growth (2023).

- Charles Kunaka et al. Transport Connectivity for Food Security in Africa: Strengthening Supply Chains. World Bank, 2025.

- Olivier Monnier. “Getting to the Root of Africa’s Food Challenges.” International Finance Corporation, December 8, 2020.

- World Bank. Zambia Economic Update: Leveraging Energy Transition Minerals for Economic Transformation (World Bank, 2025).

- Ede Ijjasz-Vasquez et al., “Leveraging US-Africa Critical Mineral Opportunities: Strategies for Success,” Brookings Institution, September 29, 2025.

- Africa’s Green Minerals Strategy (African Minerals Development Centre, 2024).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).