Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

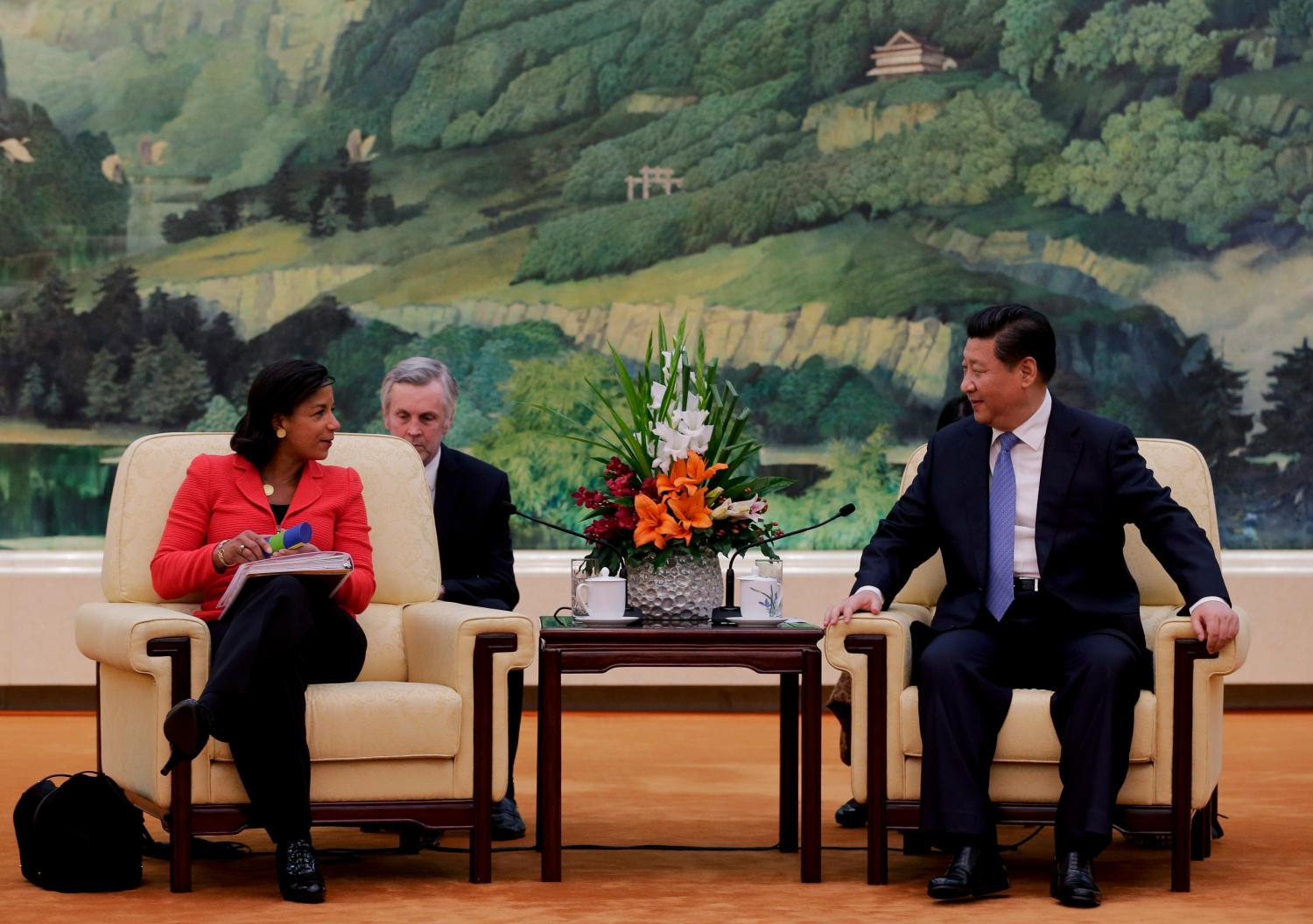

In this India-U.S. Policy Memo, Jeffrey Bader lays out the fundamental elements of the Obama administration’s “rebalancing” policy in the Asia-Pacific region, highlighting the frictions among its goals. He also considers the U.S. relationship with China, as well as the developments in the Asia-Pacific region that preoccupy American policymakers.

The Obama administration has characterized its policy toward the Asia-Pacific region as one of “rebalancing,” by which it means assigning higher priority and political, economic, and security resources to the region because of its dynamism and opportunities for the U.S. The fundamental elements of the rebalancing have included:

• Strengthening of relationships with allies and partners, including emerging powers such as India and Indonesia;

• Embedding the U.S. in the emerging political, security, and economic architecture, including the East Asia Summit, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and a more extensive and structured relationship with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN); and

• Maintaining a positive and stable relationship with China, in which cooperation on global issues develops and competition on security and economic issues is contained and managed.

There are frictions among these objectives, notably the challenges posed by the rise of China. Those challenges have been most manifest in the maritime and territorial disputes in the East China Sea between China and Japan, and in the South China Sea among the six claimants (China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Philippines, and Brunei).

Impelled primarily by these maritime disputes and actions taken by various parties, China’s relations with a number of its neighbors have become more problematic, as each sees a rising China as likely to seek to impose its will on territorial issues and as prepared to use its growing economic leverage to diminish their options. These countries, in turn, have sought American assistance and support for their claims and actions, which, in turn, has persuaded Beijing that the U.S. is orchestrating opposition to its territorial claims in order to isolate and contain China. The result has been a cycle that has damaged relations between the U.S. and China as the U.S. has sought to prevent coercion in the South and East China Seas. At the same time, many of China’s neighbors have sought to strengthen security ties with the U.S. and with each other even as they have expanded their trade and investment ties with China, already their number one economic partner.

This is not the whole story in U.S. relations with China. There are frictions, to be sure, but nothing like the tensions that marked the U.S.-China relationship during the Taiwan Strait crisis of 1996, or in the wake of the accidental U.S. bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade in 1999, or the EP-3 surveillance aircraft accident in 2001. The U.S. and China continue to expand trade and investment ties dramatically; to develop rudimentary military-to-military relations; to consult and cooperate to varying degrees on global issues such as the Iranian and North Korean nuclear programs, anti-piracy, and climate change; and to develop people-to-people, scientific, professional, and scholarly exchanges to the degree that there is substantial interdependence between the two countries.

Other developments in the region that preoccupy U.S. policymakers include:

• North Korea’s nuclear program and the erratic and unpredictable behavior of its new leader, Kim Jong-un. These have led the U.S. to strengthen U.S.-South Korea alliance capabilities, and also interestingly to improved ties between Seoul and Beijing, which is increasingly distrustful of Pyongyang’s leadership and intentions.

• The future of reform in Myanmar, and particularly the 2015 elections, which either will give a boost to reform or set it back depending on the electoral rules.

• The coup d’etat in Thailand and the prospects for return to democratic civilian rule in that deeply divided society.

• The opportunities and challenges posed by a reinvigorated Japan under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. The U.S. has welcomed Abe’s stimulation of Japan’s economy, its reformulation of its security policies including affirming the right of “collective security” with its American ally, and its regional diplomacy with India and other major partners. It has been uneasy over the deterioration of Japan’s relationships with China and South Korea, in part stimulated by maladroit handling of so-called “historical” issues relating to World War II. While the Obama administration has strongly affirmed the alliance with Japan and U.S. commitments, it does not wish to see tensions between Tokyo and Beijing and hopes the two sides at a minimum will take confidence-building measures to reduce the risk of accidental clashes around the disputed East China Sea islands (Senkakus, or Diaoyus).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).