This post is part of series by Brookings experts on Trump in 2018.

Congress is on its annual holiday break, but when legislators return to Washington in January, plenty of work and unanswered questions await them. Here are four items to pay particular attention to in 2018:

1. How long does it take Congress to clean up from 2017?

After Republicans’ intense push to meet an ambitious Christmas deadline on their tax legislation, Congress left for the holidays with a significant amount of its 2017 work undone or, at best, in a holding pattern. The latest temporary measure funding the federal government will run out on January 19. Before that deadline, Republicans and Democrats must reach an agreement on the overall size of the federal pie (that is, overall spending levels) before they can decide how exactly to divide that pie up among various federal programs.

Also left by the wayside in 2017 were various other legislative items that members of Congress hoped to attached to must pass spending bills, including long-term reauthorizations of the Children’s Health Insurance Program, a veterans’ health care program, and certain government surveillance authorities. Missed deadlines, unfinished business, and a calendar-driven legislative process are nothing new. But this year, congressional Republicans chose to meet a political target of their own creation on the tax bill, rather than deadlines for which inaction has real consequences.

2. What does an even smaller Senate majority mean for Republicans?

In early January, Senator-elect Doug Jones (D-Ala.) will be sworn in, shrinking Republicans’ already slim Senate majority one seat further, to 51. Given that most legislating in the Senate requires overcoming the threat of a filibuster, work on regular agenda items, like spending bills, won’t be substantially affected by a new Democratic senator. On those issues, the primary negotiating dynamic will remain the same: anything that can get at least nine Democratic votes in the Senate will likely anger some bloc of conservatives in the House.

Two areas, however, where the GOP’s diminished Senate majority may matter are on nominations and budgetary bills. Ending debate on nominees to executive branch positions and the federal judiciary only requires a simple majority of senators, but with only 51 seats, Republicans can lose just one of their members (and would need Vice President Pence to break a tie). The same is true for the annual budget resolution and budget reconciliation bills. Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.) has identified welfare and entitlement reform as top priorities for 2018, and while reconciliation would be an option in those policy areas, a smaller majority makes the path forward on those issues more challenging.

3. What—if anything—can Congress get done in 2018?

Beyond the 2017 leftovers discussed in #1, Congress has plenty of other items it could try to work on in 2018—but which ones will it choose? President Trump has repeatedly promised that an infrastructure proposal is weeks away, but it remains unclear when the White House will issue a formal plan and what, if anything, Congress will do with it. Many provisions in the current farm bill expire at the end of September 2018, making it a likely area of focus for the year. At present, Republicans have scheduled more time for members in Washington than in 2017, which suggests that leaders at least intend to take on an agenda in 2018. We’ll see if they stick to that schedule—especially in what will shape up to be a contentious election year.

4. What will the 2018 midterms bring?

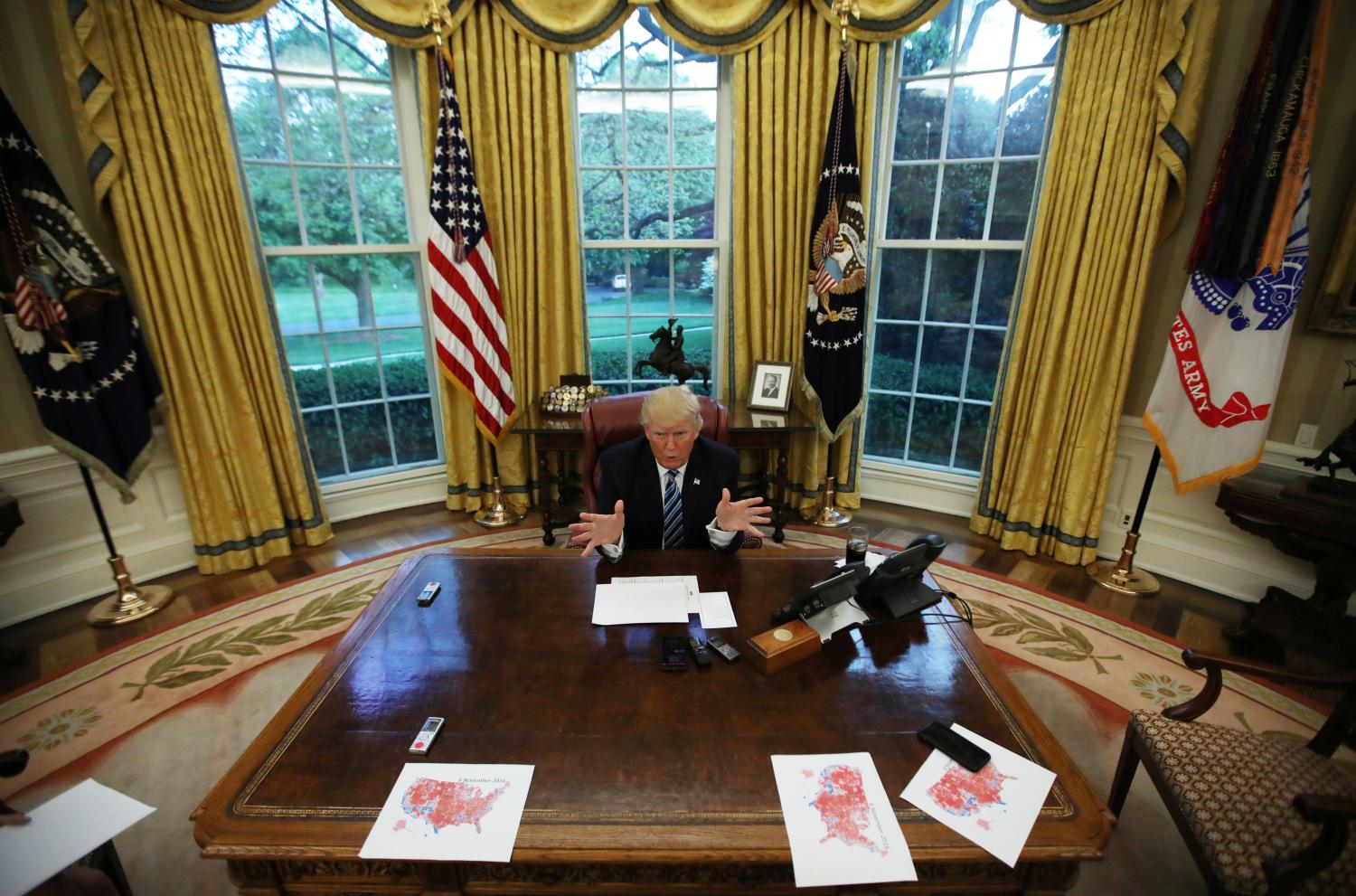

Democrats hold a substantial lead in the so-called “generic ballot,” the standard polling questions that ask respondents which party they would vote for, or would prefer, to control Congress. As Michael Malbin explained in October, Democrats have been quite successful at recruiting challengers to run against Republican incumbents and that those candidates have been doing well at raising money. Democrats, he argues, “are poised to take advantage of a wave if one develops.” My colleague, John Hudak, wrote this week, “No party likes to be in incumbent protection mode, but eleven months from the midterms, Republicans face real challenges while Democrats transfer resistance into mobilization.” Given the increasing nationalization of congressional elections, whether such a wave develops will be largely the result of national political forces, including President Trump’s popularity.

Between the failed health care bill, successful tax legislation, unexpected resignations and election results, 2017 has been a year to watch in Congress; 2018 is likely to provide more of the same.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Trump in 2018: Four things to watch in Congress in 2018

December 29, 2017