Note: This post originally appeared in a December 5, 2014

Health Affairs Blog and corresponds with the Engelberg Center’s event, MEDTalk: Transforming Rural Health through Telehealth and Education.

Health care for patients in rural communities across the United States remains a unique challenge. Despite many programs aimed at improving access to physicians and hospitals, access to health care providers remains limited. While 19.3 percent of Americans live in a rural area, only about 10 percent of physicians practice in rural areas. Similarly, 65 percent of all Health Professional Shortage Areas are in rural areas. Rural residents often face long travel distances to see a specialist after what can be months waiting for an appointment.

Even in areas where rural primary care providers (PCPs) remain committed and engaged in the community, often having been raised and educated there, these providers often lack close connections to specialists who tend to be based in larger, urban academic medical centers (AMC). The result is a worsening gap in specialty care access, in turn leading to a deteriorative effect on rural provider morale and retention.

Most of the efforts to improve rural care date have focused on enhancing the patchwork of federally regulated safety net programs, with thegoal of increasing quality of care by increasing access to primary, routine and emergency care. However, innovative communications technologies, decision support tools, and initiatives to enhance “broadband” access in rural areas are enabling frontline rural health care professionals, and even patients and family members themselves, to implement new approaches to delivering high-quality care even with limited availability of physicians, and particularly expert physicians. In this post, we review some of the promising new approaches to delivering high-quality care in rural areas, and consider new payment reforms that could provide better support for these approaches.

Transforming Rural Specialty Care

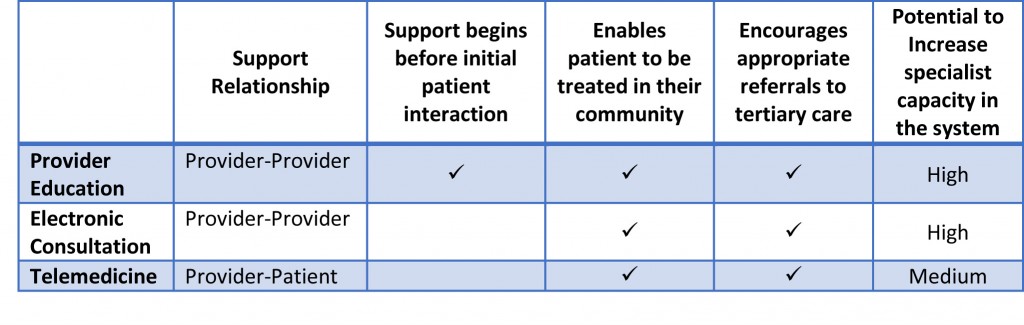

New technologies that support communications between PCPs and specialists can overcome some of the traditional problems of patients’ access to up-to-date specialist care while still enabling patients to be treated in their communities. Three main approaches to using technology are virtual learning, electronic consultation, and telemedicine. Virtual learning supports rural providers to increase their knowledge of specialty-specific clinical medicine in order to provide greater care for their patients with certain conditions. An electronic consultation can take many different forms, but is usually a virtual exchange initiated by a primary care provider in order to seek guidance from a specialist outside of a face-to-face visit. Telemedicine is defined as a, “two-way, real time interactive communication between the patient, and the physician or practitioner at the distant site” which sometimes takes the form of a patient arriving at a local clinic to meet with a specialist remotely via interactive video teleconferencing.

In addition to enabling more patients to receive quality care within their communities, these approaches can also support PCPs to make more appropriate referrals, ensuring that only those most in need of treatment at a tertiary center are referred.

Figure 1: Comparison of technological solutions to support PCP/specialist communication

It is important to distinguish the appropriate context for each of these different approaches to increasing access to specialty care in rural communities. Low intensity conditions with a reasonably high prevalence may benefit most from electronic consultation and provider education programs. An example of a successful implementation of these approaches is the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes program (Project ECHO), which hosts virtual case-based learning conferences and grand rounds. Originally established as a project at the University of New Mexico for treatment of Hepatitis C, it has since expanded to include additional medical conditions such as HIV, chronic pain, diabetes, and behavioral health, and has been replicated nationally.

Telemedicine may be more appropriate for high intensity conditions because the skills required for clinical management may not be appropriate for primary care providers. While this approach does not actively increase capacity in the system, it can be used in collaboration with educational approaches. An example of this approach is the Antenatal and Neonatal Guidelines, Education, and Learning System (ANGELS) based out of the University of Arkansas Medical School. This program applied telemedicine and provider education to treating high-risk pregnancies throughout the state and has since expanded into other high intensity areas such as perinatal bereavement, stroke and spinal cord injuries.

In addition to improving quality and capacity of care within rural communities, these approaches also have the potential to generate cost savings. Receiving more specialized treatment from a PCP may reduce complications and emergency department visits as well as the volume of costly and unnecessary referrals to tertiary centers. Provider education and electronic consultation approaches may also provide cheaper ‘junior’ specialty care as this dissemination of knowledge enables PCPs to provide more care themselves.

Payment Reforms to Sustain and Enhance Rural Specialty Care

Despite this potential for improved care and cost savings, the United States health care system is not set up to recognize and reward these approaches. Because they represent a transformation of traditional health care facilities and in-person consultations and services, they are often not supported under traditional fee-for-service (FFS) payment systems like Medicare. As a result, many health care organizations implementing these innovations are funded through grants.

This reliance on grant funding leaves programs without a sustainable funding model because the renewal of grants is uncertain. It also leaves gaps of accountability among the providers involved in care, as these grants do not currently financially support the PCPs for their time. Some programs have begun to receive financial support for these services in new reimbursement models, including person-level, per member-per month (PMPM) payments.

While it may be tempting to incorporate a PMPM or an increase in the number of services reimbursed under FFS to support these approaches, these changes may leave payers worried that they may not see an increase in quality that is proportional to increased costs. In order to improve quality and control costs, reforms in care will need to be well-coordinated with existing care systems.

More evidence and experience is needed to find the best ways to support high-quality, affordable specialty care in rural communities. For example, Project ECHO in New Mexico receives a PMPM to the AMC for the time their specialists spend in the program, but the PCPs do not receive any funding. In the case of ANGELS, specialists receive the same FFS payment they would receive for seeing a patient face-to-face, while local providers only receive a nominal location fee.

Further payment reforms might involve a better-coordinated mixture of FFS and PMPM payments to provide more resources to these innovative approaches to care. For example, a model that combines payments (and shares savings) across specialty providers and PCPs would encourage the communication and stronger professional networks. When considering the appropriate model it will, therefore, be important to compare options not only by how the payments are structured for individual providers, but also their level of aggregation across the different providers involved.

Further steps in rural payment reform will likely benefit from better performance measures to assure that the new payment methods are achieving their intended goals, aligning the new payments with delivery transformations that work. Appropriate measures might assess improved patient- and population-level outcomes and experience with care. These might include measures related to utilization for a population of rural patients, such as hospital readmission rates. However, outcome measures can be particularly unreliable or difficult to collect for small and heterogeneous populations like those in many rural communities.

Alternatively, measures might relate to the use of evidence-based processes of care, such as dissemination of specialist information among providers, use of specified protocols and provider knowledge, and use of appropriate settings of care. For example, ANGELS measures the percentage of very-low-birth-weight deliveries that occur in the AMC. These measures could assess impact on reducing barriers to specialty care (for example, percentage of treatment in community, time to treatment, average distance, and time travelled for treatment).

As additional innovative models of rural specialty care are implemented, and as experience accumulates with effective ways to improve specialist access and decision-support for PCPs, the future for quality of care in rural areas may be bright. But to sustain and accelerate effective reforms in care delivery, new payment approaches will likely be needed. In conjunction with efforts to expand access to care in the Affordable Care Act, Medicare reforms, and other programs, these rural payment and health care delivery reforms can play a critical role in improving care while containing cost.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edTransforming Rural Health Care: High-Quality, Sustainable Access to Specialty Care

December 5, 2014