This essay was originally published on MasterCard Center for Inclusive Growth.

There is much soul-searching on both sides of the Atlantic about the voter discontent that led to Britain’s coming exit from the European Union. One facet of that frustration—that global integration isn’t working for everyone—is indeed playing out in the United States. Today, many Americans are not benefiting from economic gains.

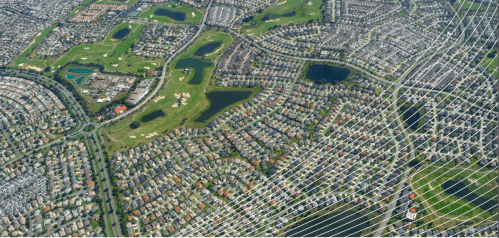

Our program at Brookings examines how economic growth and opportunity play out in cities. Not only are cities and their broader metropolitan areas the centers of innovation and trade, but they are also places where most people go to seek jobs and opportunity. While cities vary greatly in their economic prospects, one common pattern is clear from our recent analysis, at least in the United States: economic growth is not translating to economic inclusion. Here are three key findings from our research:

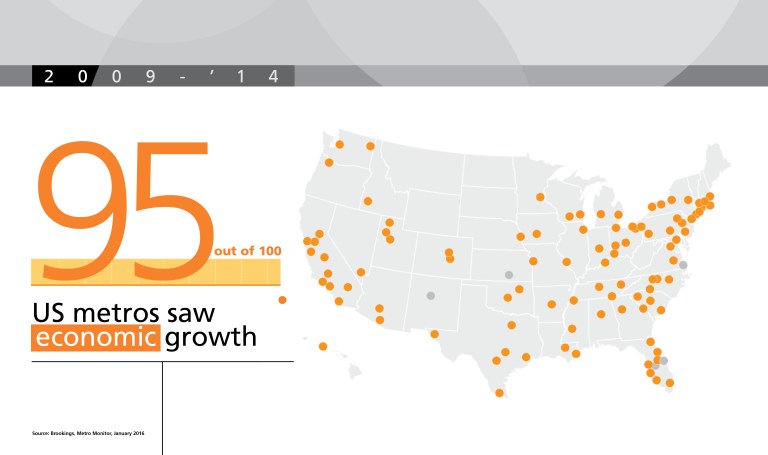

Nearly all—95—of the 100 largest U.S. metropolitan areas experienced economic growth in recent years. Economic growth is essential to expanding opportunity. More jobs and tighter labor markets help boost wages. Nearly all the nation’s largest metro areas added jobs, aggregate wages, and total output since 2009, reflecting the broader expansion of the U.S. economy. But degrees of growth varied across the nation. Some metros grew rapidly, fueled by technology and energy booms: Houston’s number of jobs increased by 14 percent in five years, while San Jose’s output increased by 29 percent over the same timeframe; other metros, particularly in the Sun Belt and Northeast, grew at a much slower pace.

Nearly all—95—of the 100 largest U.S. metropolitan areas experienced economic growth in recent years. Economic growth is essential to expanding opportunity. More jobs and tighter labor markets help boost wages. Nearly all the nation’s largest metro areas added jobs, aggregate wages, and total output since 2009, reflecting the broader expansion of the U.S. economy. But degrees of growth varied across the nation. Some metros grew rapidly, fueled by technology and energy booms: Houston’s number of jobs increased by 14 percent in five years, while San Jose’s output increased by 29 percent over the same timeframe; other metros, particularly in the Sun Belt and Northeast, grew at a much slower pace.

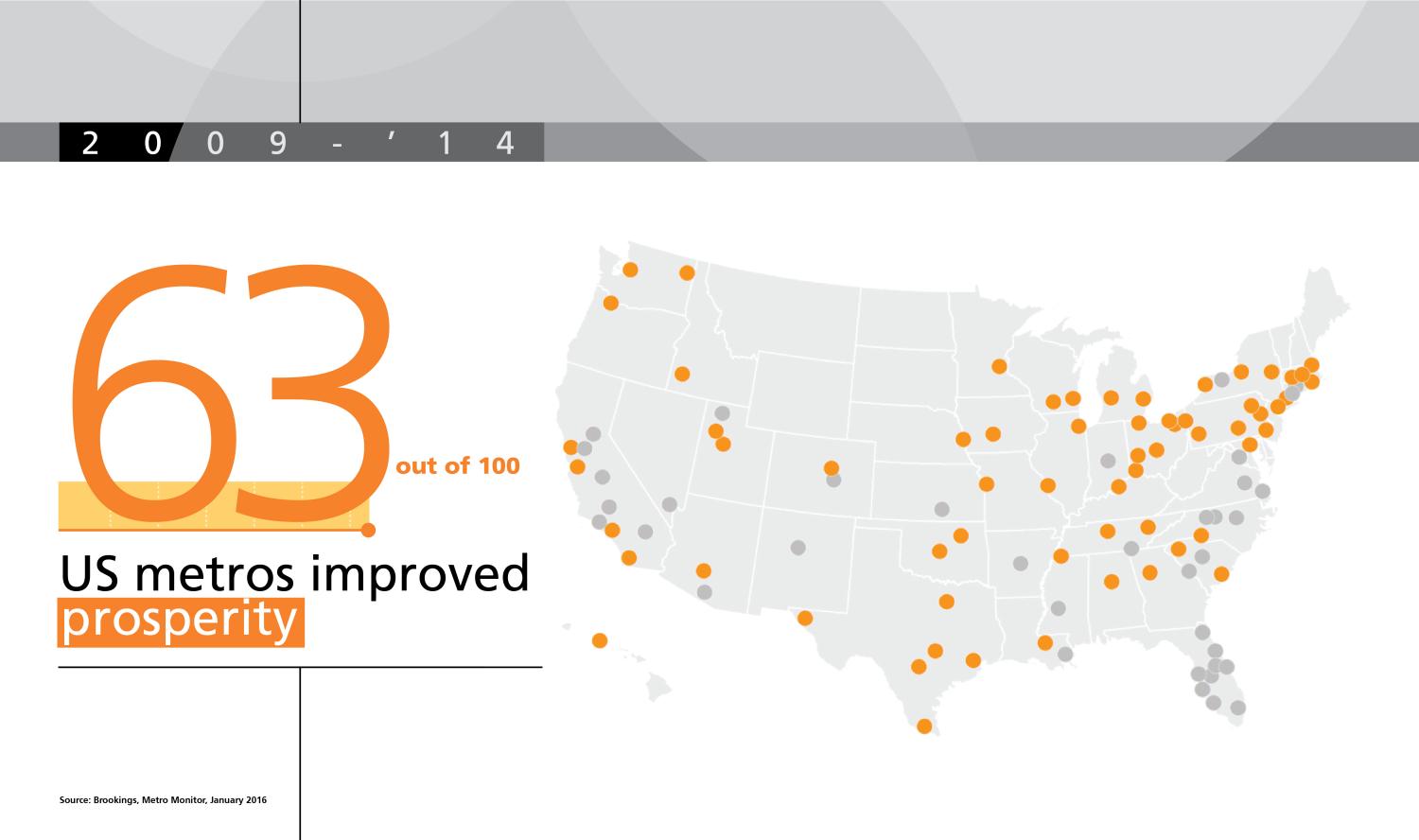

A smaller proportion of metropolitan areas—63 percent—experienced improvements in prosperity. While growth matters, how a region grows matters more. A new manufacturing facility and a big-box retail store may create the same number of jobs, but the first business typically adds much more value to the region than the second. Over the past five years, the economies of just 63 metro areas grew thanks to the improved productivity of firms and higher average standards of living for workers and families. At the same time, one-third of metropolitan areas – including many in North Carolina, Florida, and California’s Central Valley – did not see economic growth translate to greater prosperity for residents.

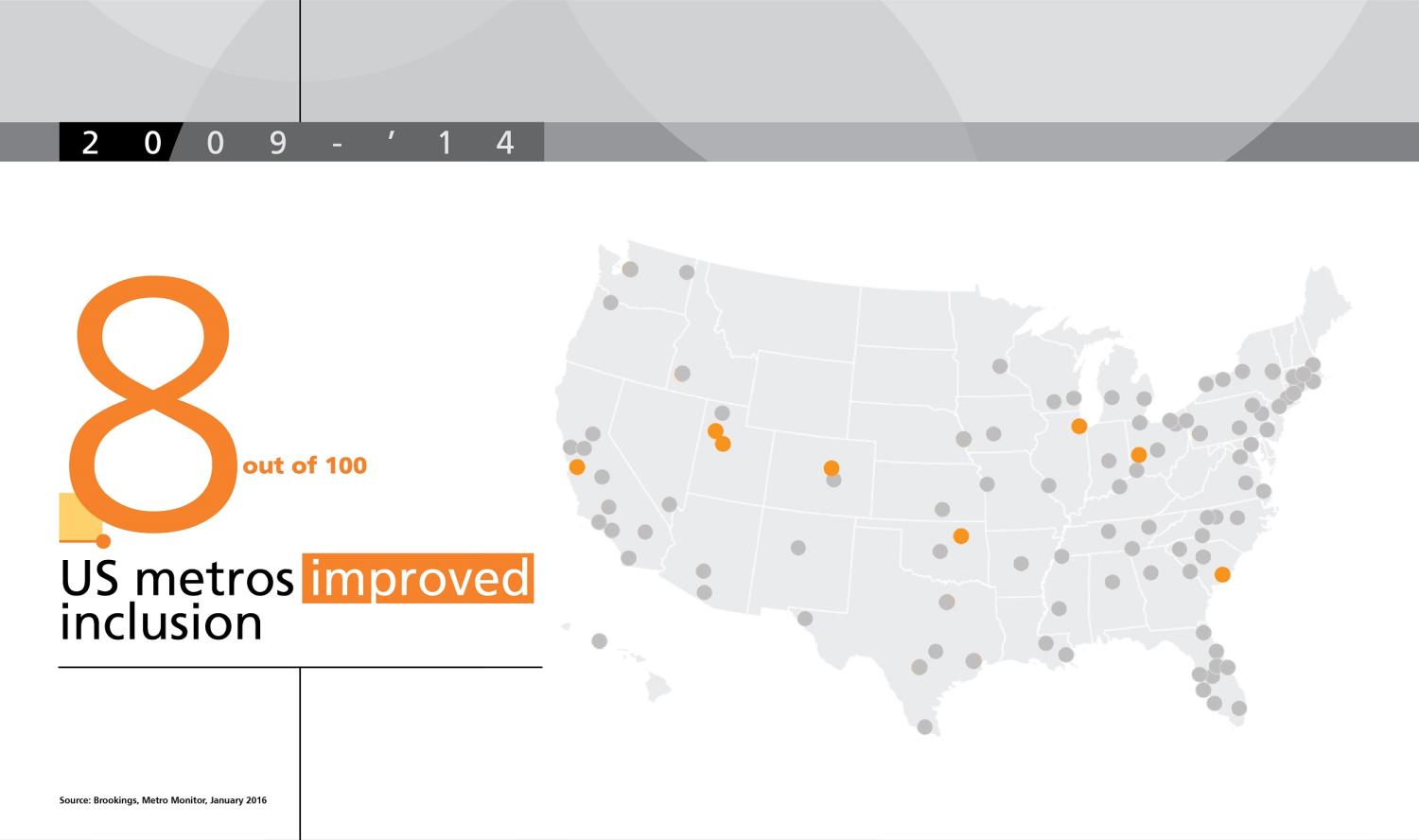

Only a handful of metropolitan areas improved on economic inclusion. Only eight of the 100 largest metros saw growth and prosperity produce gains for workers through rising employment, higher median wages and a reduction in the share of workers earning extremely low wages. Instead, the median wage fell in 80 metros, and the share of extremely low-income workers increased in 53. For nearly all metros, growth and productivity gains simply aren’t leading to benefits across most income levels.

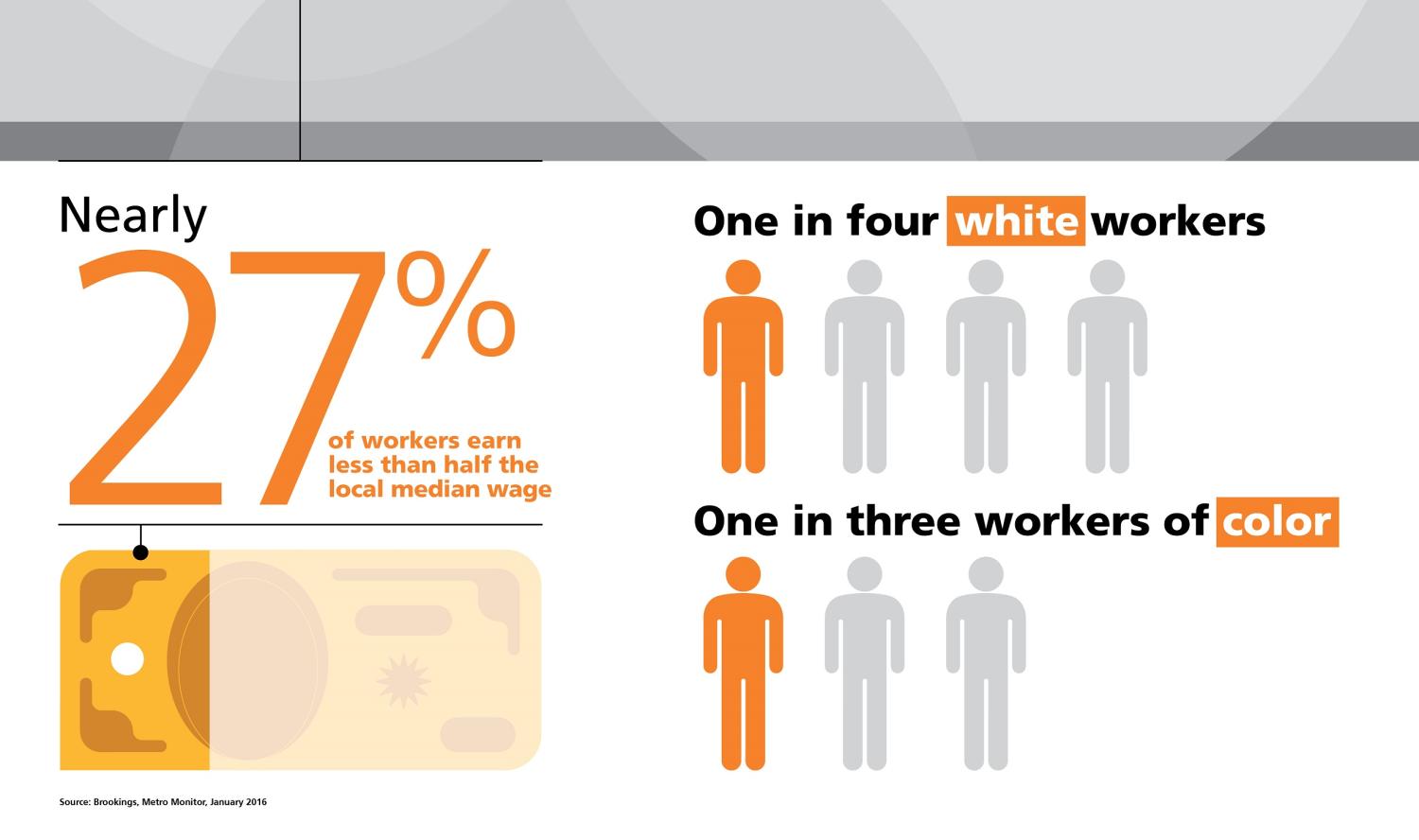

These findings reflect two structural trends: the changing demographics of the American workforce and the increasing polarization between low- and high-paying jobs. Older, whiter generations, including Baby Boomers, are beginning to retire while younger, more diverse generations are joining the labor force. Yet black and Hispanic workers tend to earn lower wages than their white counterparts, bringing the overall median wage down as workers of color become a larger share of the workforce. At the same time, many of the private-sector jobs that have been added since the Great Recession are either in high-paying professional service sectors or in lower-paying industries such as retail, with few well-paying jobs available for workers without advanced degrees.

The polarization of jobs in the US has led to an uptick in the share of workers who earn low wages in these metros, from 25.5% in 2009 earning less than half of the local median wage to 26.7% to 2014.

The eight metropolitan areas that saw across-the-board gains on inclusion – Charleston, Chicago, Dayton, Denver, Provo, Salt Lake City, San Jose, and Tulsa – do not share a common economic story.

Some, like San Jose and Denver, have experienced rapid growth fueled by the success of local high-paying industries, such as energy and tech. Others, like Salt Lake City and Provo, are less diverse and haven’t experienced as many of the disruptive effects of generational demographic change. Still others, like Dayton and Chicago, were hit particularly hard by the recession; their improvements on inclusion appear to be largely a rebound from difficult times.

One takeaway from our research is that strategies to create economic growth are necessary but insufficient, while those to improve prosperity and inclusion require greater attention and intention. In the depths of the recession, many city leaders prioritized job creation, and justifiably so: with metropolitan economies in a tailspin and unemployment rising sharply, getting people back to work was essential. But our research is a stark reminder that growth alone does not deliver rising productivity or living standards for all. As I describe in a recent report, metropolitan areas are pioneering new strategies to create the conditions for continuous growth, prosperity, and inclusion. They are setting new metrics for success beyond GDP growth including measurements of job quality, high school graduation rates by race, and share of jobs accessible by public transportation. Their strategies are focused on boosting income and productivity through trade, innovation, and investments in skills training for workers. City leaders are mindful that regional cluster strategies must work alongside efforts to rebuild the central city or connect distressed neighborhoods to regional opportunities. These strategies are built for the long run, less easily measured than simple “jobs created” statistics, but are critical to improving the prospects of people and communities in metropolitan areas.

In both the United Kingdom and the United States, voter frustration stemming from a lack of inclusive economic growth is fueling appetites for drastic change. In the United States, such frustration is likely to become most acute in the nation’s largest metropolitan areas, where more than two-thirds of Americans live and work. It’s time for city and metropolitan leaders to respond with innovative, targeted solutions that will create an advanced economy that can work for all.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Tracking economic growth, prosperity and inclusion in US metros

August 2, 2016