The slow-motion crisis between Iran and the United States picked up tempo this week with Tehran’s announcement that it will soon defy restrictions set by the 2015 nuclear deal on its stockpile of low-enriched uranium. Tehran’s first major step away from the nuclear accord since the United States exited the deal in 2018 comes in the wake of a series of attacks on tankers in the Persian Gulf, as well as missile and drone strikes directed at Saudi and Emirati infrastructure and American presence in Iraq. The latest spasm of violence played out even as the Japanese prime minister left Tehran empty-handed after a mediation effort apparently encouraged by President Trump.

Iran’s impending breach of the nuclear deal (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA) and the attacks in the Gulf reflect the increasing desperation of Iranian leaders as the stranglehold of sanctions reimposed by Trump intensifies. This is not simply knee-jerk Iranian counterpunching; rather, the rising tensions are an acknowledgement that Iran cannot afford a protracted impasse, with uncertain hopes of economic relief from some future U.S. administration. Facing an economic abyss and anticipating consequent domestic political fallout, Tehran has recently begun to cast aside its self-imposed restraint and test the world’s response to calibrated reprisals. The only surprise is that Iran’s vengeance has taken so long and—until this month—amounted to so little.

Iran is now injecting a sense of urgency within the international community around devising a pathway out of its simmering standoff with Washington. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader, recently explained that negotiating from a position of weakness is a trap, and the only recourse for a country under U.S. pressure is to utilize its own “pressure tools” to induce Washington to alter its approach. Escalation is a dangerous way to accrue leverage, but Tehran is well versed in using provocation to gain advantage.

The images of burning tankers in the world’s most important energy corridor has stoked fears that the United States and Iran are on a collision course. There is legitimate cause to worry that neither side has the skill—or the will—to avert a conflict. The stakes are high, but it’s not too late to forestall yet another catastrophic American military intervention in the Middle East. The latest skirmishing underscores the risks of what has become a strategic impasse between Washington and Tehran, one that will end in disaster for both sides if they continue along their current strategies. And for all the rhetorical fulminations and engrained animosity, influential constituencies on both sides would prefer to avoid a confrontation. The challenge now is to temper nerves and begin to develop a realistic framework for diplomacy.

A predictable tit-for-tat

The latest incidents mark a dangerous new escalation in the simmering standoff between the United States and Iran, puncturing a full year of relative calm that prevailed around Iran even as Washington upended the nuclear pact in 2018 and launched a full-frontal assault on Iran’s economy. The U.S. campaign has intensified significantly since early May, as the White House abruptly ratcheted up efforts to halt Iranian oil exports, designated its elite military force as a foreign terrorist organization, unveiled new sanctions targeting Iran’s steel and petrochemical industries, revoked some permissions necessary for Iran to continue complying with the nuclear deal, and pointedly bolstered U.S. military posture in the Gulf.

In the wake of those moves, tensions mounted quickly with a series of incidents that included attacks on oil vessels and pipeline infrastructure in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, the emergency departure of some U.S. diplomats from Iraq, reports that the White House was reviewing military options for Iran, a rocket attack on the “green zone” near the U.S. embassy in Baghdad, and a missile strike on a Saudi airport by Iranian-backed Houthi rebels that wounded 26 civilians. This week, several sites in Iraq that house American and Iraqi personnel have been struck by rockets or mortars, including several military bases and a U.S. oil company facility. Trump has used his itchy Twitter fingers to respond, warning in mid-May that any conflict would mean “the official end of Iran,” and the administration has incrementally expanded U.S. deployments to the region in response to the series of attacks.

If Iran wants to fight, that will be the official end of Iran. Never threaten the United States again!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 19, 2019

None of this should come as a surprise. In fact, backlash by Tehran is the predictable and widely anticipated consequence of Washington’s “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran. Counterattack is central to Iran’s deterrent strategy; for a leadership whose worldview was forged by Saddam Hussein’s 1980 invasion and the brutal eight-year war that followed, the conviction that yielding to pressure only invites its intensification is deeply engrained. Tehran’s aversion to submission is well understood in Washington, and for many on the right, it drives the calculation that the application of overwhelming force offers the only way to dissuade Iran from destabilizing policies.

The Trump administration has approached Iran from that mindset, launching a premediated, gratuitous effort to try to push Tehran to the brink of economic collapse. This is in fact the centerpiece of Trump’s Middle East strategy. And yet, the White House appears to have failed to devise a game plan for managing the consequence of a foreseeable flare-up of tensions—or equally importantly, for achieving its vague but ambitious objective “for Iran to behave like a normal nation,” reiterated recently by Brian Hook, the U.S. special envoy on Iran.

Whether the failure to plan for obvious contingencies signals an intentional recklessness by the White House or is simply a byproduct of this administration’s dysfunctional policy process—or some combination of both—it has brought us to the current saber-rattling, which has spooked oil markets and elevated Iran near the top of an already crowded array of urgent challenges for Washington.

Sanctions success

In terms of sheer impact, Trump’s policy on Iran has outperformed the expectations of its critics in Iran and in the West. Over the course of the past year, any hope that Europe could even partially counterbalance the re-imposition of U.S. sanctions was quickly disabused, as firms and financial institutions beat a hasty path to extricate themselves from their post-JCPOA forays back into the Iranian market. Since November, when U.S. measures targeting oil exports went back into effect, Tehran has struggled to maintain production—which has now fallen to five-year lows—and early signs suggest that broad compliance with even tougher restrictions imposed in May might drive exports down by another 500,000 barrels per day or more.

All this has had a devastating effect on Iran and Iranians. Tehran has hard-earned expertise in the art of circumventing sanctions and insulating the country against their blowback. However, the combination of Washington’s uncompromising implementation and the atrophy of Iran’s resilience as a result of long-term mismanagement, corruption, and sanctions has blunted Tehran’s capacity to deflect the latest blows. Over the past year, the value of the Iranian currency has sunk by two-thirds, inflation is approaching 40%, and per the IMF, the economy is expected to shrink by 6% this year.

And even though agricultural products and medical goods are exempted from all U.S. sanctions, prices for basic goods, including many foodstuffs, have doubled or tripled, and many medicines are in short supply. Iranians wait for hours in snaking queues for subsidized meat supplies and the government is considering reinstating the ration system that sustained the country through its ruinous war with Iraq. The possibilities that briefly seemed within reach during the halcyon afterglow of the nuclear negotiations have been supplanted by a grim, jittery state of siege.

The possibilities that briefly seemed within reach during the halcyon afterglow of the nuclear negotiations have been supplanted by a grim, jittery state of siege.

Among the other parties to the nuclear deal—Britain, France, Germany, Russia, and China—there is genuine sympathy with Iranians’ plight and some real bitterness over the Trump administration’s noxious unilateralism. But they have few realistic mechanisms for mitigating the fallout. None of these capitals can compel banks and companies to do business with Iran, and even if they could, they have no interest in placing their own economies and industries in the cross-hairs of the U.S. Treasury Department. And based on broader shared interests and the presumption of some eventual return to multilateral cooperation on Iran, the Europeans in particular have sought to avoid a full-fledged breach with Washington on Iran policy. As a result, the wide condemnations of Trump’s exit from the nuclear deal have produced little in the way of tangible compensation or assistance to Iran.

Cautious provocation?

Tehran has few good options for changing those calculations to its advantage, which explains why its response to Trump’s “maximum pressure” policy has been far more measured than most of the apocalyptic predictions of observers and advocates a year ago. None of the policy responses available to the government—such as defying the nuclear deal in its entirety or lashing out openly at U.S. interests or assets—offer a viable pathway to extricating Iran from the American vise grip or ameliorating the potentially existential threat to the Islamic Republic posed by perpetual and far-reaching U.S. sanctions. Even for measures that offer a modicum of plausible deniability, such as cyberattacks, Tehran’s retaliatory repertoire might only exacerbate its current predicament.

As a result, Iranian leaders have absorbed the wallop of “maximum pressure” sanctions with uncharacteristic prudence, particularly since Trump’s exit from the JCPOA. Even after 12 months of full-frontal assault on the nuclear deal by the Trump administration, the agreement remained still firmly entrenched, even as the standoff between Washington and Tehran has escalated. Only in the past few weeks has a relatively measured Iranian pushback begun to manifest—long after it had been established that the international community would take no heroic measures to extricate Iran from the punishing blows of American sanctions and only after Washington sought to further intensify the blockade by denying waivers for continuing Iranian oil exports.

On the nuclear deal, Iranian leaders waited a full year after the U.S. withdrawal from the deal to initiate a series of modest, calculated escalations of their own, ending their adherence to several JCPOA commitments. This was meant to deliver on the warning that they have sought to convey since Trump began to take aim at the deal—namely, that reciprocity is essential to the survival of the agreement and its restrictions on Iran’s nuclear activities. In the immediate aftermath of the U.S. withdrawal, Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei declared that “the Iranian nation and its government will not tolerate to be both subject to sanctions and have its nuclear programme restricted and imprisoned.”

Nonetheless, thus far Tehran has deliberately avoided steps that would fatally compromise the agreement. If the intent were to jettison the JCPOA permanently, Iranian leaders could undertake far more drastic steps, such as abandoning its implementation of the Additional Protocol to the Non-Proliferation Treaty or introducing advanced centrifuges into the Fordow underground enrichment facility. These (and other) possibilities have been dangled as possibilities by Iranian officials, but to date Tehran’s steps away from the deal are more restrained and reversible. In fact, Tehran’s decision to forgo JCPOA limits on enriched uranium and heavy water stockpiles was essentially preordained by the recent U.S. re-imposition of restrictions on exporting Iran’s nuclear production, although Tehran has sped up the timeline for the breach.

The signals sent by the incidents in the Persian Gulf are even more pointed. Iranian involvement is not yet independently confirmed, but there is credible and growing evidence to support suspicions that Tehran had a hand, via its clientelistic relationship with Houthi militias in Yemen, in last month’s sabotage of oil tankers docked at Fujairah in the United Arab Emirates and the drone attacks on two pumping stations along the East-West pipeline that crisscrosses Saudi Arabia. Notably, both attacks targeted infrastructure specifically designed to bypass the Strait of Hormuz, elements of the contingency planning put in place over decades by the Gulf states to mitigate their vulnerability to Tehran. And in both cases, the damage was relatively minimal, reducing the likelihood of collateral damage and/or an escalatory American response.

In last week’s attacks on tankers in the Gulf of Oman, Iran appears to have ratcheted up the risk factor, but only incrementally. Damaging vessels at sea, rather than in port, in a busy shipping channel heightened the possibility of exposure or civilian casualties. Still, by targeting smaller ships that were not carrying crude oil, and undertaking attacks that appear designed to damage rather than sink the ships, the latest attacks seemed designed to preclude a real game-changer in terms of security or environmental fallout.

Through its calculated reprisals, Tehran underscores its comparative advantages of proxy militias and unconventional warfare and its ability to push back against U.S. pressure in ways that minimize the risks of a direct confrontation. This enables Iranian leaders to make good on their longstanding doctrine that links the security of its energy exports to that of its neighbors. As a member of the Iranian parliament warned in 2012, echoing countless Iranian security officials both before and since: “If the world wants to make the region insecure, we will make the world insecure.” Jeopardizing its neighbors’ energy exports offer more than simply the satisfaction of revenge; the mere threat to disrupt supply can produce price spikes, improving Tehran’s beleaguered bottom line for whatever exports it manages to preserve. Equally importantly, higher oil prices could complicate Trump’s reelection prospects, which rest heavily on the administration’s claims of economic improvements.

Keep calm

The Trump administration may be tempted to up the ante in response to these latest provocations by Iran. That would be a mistake. The administration’s bellicose, go-for-broke tactics for dealing with Iran are fundamentally at odds with Trump’s determination, repeatedly and firmly expressed, to extricate the United States from costly and protracted military conflicts in the Middle East. Despite persistent trepidations that Trump’s advisors are bent on provoking a conflict Tehran, the president himself has privately dismissed military escalation and publicly downplayed the significance of the latest skirmishing. However, the contradictions within current American approach have produced a strategic quagmire. “Maximum pressure” has proven insufficient to produce Iranian collapse or capitulation, and Tehran’s ability to scrape by under duress has not mitigated the existential challenge facing its leaders or dissuaded Washington’s strong-arm tactics. Neither Washington nor Tehran can prevail unilaterally or unequivocally, and each side’s strategy poses deeply problematic risks for its adversary.

The United States clearly has the upper hand: Trump’s maximum pressure can drive Iran’s economy toward the brink of collapse, constraining its capacity to fund its proxies and regional military adventures and intensifying dissatisfaction with and among its ruling elites. Unfortunately, however, U.S. policies alone cannot achieve the administration’s stated objective, Iran’s transformation into “a normal nation”; that’s ultimately in the hands of Iranians and their leadership. It is certainly possible that crushing economic pressure may expedite Iranians’ long, hard path to more responsible governance, but it’s at least equally possible that deprivation at the hands of an external threat will empower an even more dangerous clique of Iranian demagogues.

Although Tehran effectively cannot insulate its economy against U.S. sanctions, the country is hardly defenseless. As the world has witnessed over the past six weeks, its leaders can strike back in ways that hit the Trump administration where it hurts—in the economy, via moves that disrupt supply or merely create uncertainty to spike oil prices just enough to further slow growth in the global economy and disenchant Trump’s voter base at home. Iranian-backed militias can raise the temperature for U.S. partners in Iraq and Afghanistan, and for the U.S. troops still positioned there. The blowback from any direct escalation between U.S. and Iranian forces would not remain limited to Iran; it would ignite the region and incur human, financial, and electoral costs that no one in the United States is prepared to pay without a real imperative, especially in an election year.

Until recently, Iran has displayed restraint in responding to the challenges its leadership is facing.

Until recently, Iran has displayed restraint in responding to the challenges its leadership is facing. But as these latest events demonstrate, Iranian restraint is not a reliable mechanism for averting a conflict. And the long-term application of pressure without diplomacy, as some within the Trump administration may prefer, will leave Washington in a dangerously weak position to deal with the threats just beyond the horizon today. Should the Islamic Republic somehow manage to muddle through, the end of the constraints on its nuclear program will be within sight by the next U.S. president’s inauguration. Without some successor or replacement for the JCPOA, Iran will be only a few years away from an internationally-legitimized nuclear program with few meaningful obstacles to weapons capability.

Seeking another path

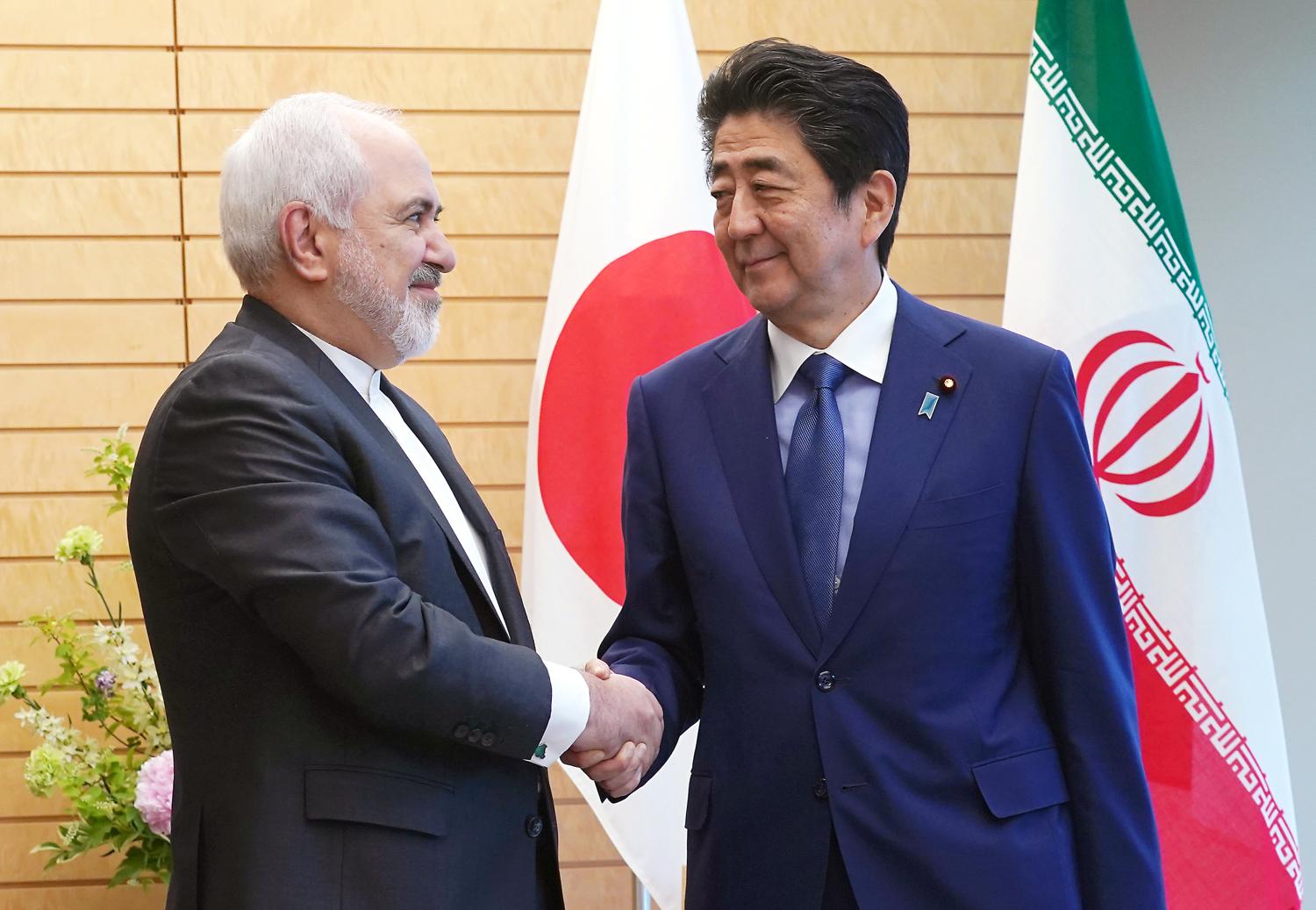

What is needed now more than ever is a serious diplomatic initiative to begin devising some framework for managing the profound challenges that Iran poses to regional and international security. Trump has publicly appealed for direct dialogue with Iranian leaders on a number of occasions; he apparently asked Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to undertake a mediation effort and even reportedly went far as to have the telephone number for the White House relayed to Tehran via official diplomatic channels. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo emphasized earlier this month that the administration has no preconditions for talks with Iran and is ready to engage directly with Tehran.

Iran’s senior leadership is far less accommodating, insisting that they will not negotiate with a knife to their throats and categorically rejecting the idea of bargaining over what they describe as the country’s essential defensive capabilities, such as missiles. Beneath the surface, however, Iran’s political establishment has quietly speculated for months about the possibilities for devising a diplomatic pathway out of the country’s current predicament, and there has been a flurry of Iranian engagement with would-be intermediaries. Well-known dissidents and moderate politicians recently released an open letter calling for unconditional talks, while reformist politician Mostafa Tajzadeh pointedly noted that negotiations with Washington can take place before a military conflict or afterward.

The latest New York visit by Iran’s foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, signaled that Tehran is prepared to test the waters, if only narrowly through discussions around prisoner swaps. Two months ago, Zarif delivered a virtuoso performance on Fox News, aimed at an audience of one in the White House, playing to Trump’s narcissism and his mistrust of his hawkish advisors. Last week, Tehran went even further, with the release of Nizar Zakka, a Lebanese man with permanent resident status in the United States, after more than three years’ detention on bogus espionage charges.

Now is the time to move beyond signaling and accumulating leverage at such high cost. The Trump administration should seek to develop a serious diplomatic process with direct bilateral engagement with Tehran. Expectations for this diplomacy should be clear-eyed and limited; there is no realistic prospect of achieving a comprehensive agreement that addresses the ambitious scope of concerns outlined by Pompeo last year. But the experience of the Bush and the Obama administrations demonstrates that direct dialogue can provide modest openings to resolve concrete issues, such as Iran’s unjust detention of Americans, as well as opportunities for mutual de-confliction and confidence-building around the regional conflicts where both militaries are engaged. With time, a reliable channel between Washington and Tehran can provide the foundation for more serious negotiations around some future extension of the JCPOA’s limitations on Iran’s nuclear program as well as the other issues of concern.

And balancing U.S. pressure with diplomacy would have broader benefits for the Trump administration. The reflexive public skepticism that greeted the administration’s assertion of Iran’s role in the latest attacks is evidence of a deeply problematic erosion of Washington’s credibility. A serious bid at diplomatic engagement with Tehran, particularly in concert with allies, would begin the long process of restoring confidence in American intelligence assessments and strengthening U.S. deterrent capabilities.

From hypotheticals to action

Trump’s Iran policy appears to be trying to bridge the core premises of two contending visions of U.S. foreign policy, one grounded in the muscular reassertion of American preeminence and the other bounded by a sense of restraint and pragmatism borne of the two ruinous and as-yet unfinished wars. Critics of the Iran nuclear agreement fulminated that the administration and its European, Russian, and Chinese partners in the negotiations settled too cheaply. As Senator Tom Cotton reflected in 2017: “These were the toughest sanctions Iran had ever faced, and they helped to drive the regime to its knees. One thing I learned in the Army is that when your opponent is on his knees, you drive him to the ground and choke him out. But President Obama extended a hand and helped the ayatollahs up.”

Cotton and other opponents of the nuclear deal insisted that with sufficient time and stringent enforcement, the crippling sanctions then in place could have elicited much more strenuous restrictions on Iran’s nuclear capabilities as well as far-reaching concessions around its regional posture. This tempting hypothetical has become an article of faith for many, including the Republican establishment and leaders from Israel, Saudi Arabia, and other Gulf states. Now is the perfect time for advocates of more ambitious diplomacy with Tehran to put their money where their mouth is.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edThere is an off-ramp in the U.S.-Iran crisis

How not to miss it

June 19, 2019