On June 4, the Center on the United States and Europe hosted the 20th annual Raymond Aron Lecture featuring keynote remarks from Camille Grand, distinguished policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. This is discussant Peter Rough’s response to Grand’s delivered remarks. An additional response from discussant Mara Karlin is also available.

Camille Grand’s thought-provoking Raymond Aron Lecture sketches scenarios for the transatlantic relationship for the years ahead. Those scenarios are extrapolated, in part, from the European Council on Foreign Relations’ well-known tripartite framework for understanding the dominant strains of Republican party foreign policy: restrainers, prioritizers, and primacists.

This organizational structure provides a useful mental map for interpreting the foreign policy debates playing out within the contemporary GOP. Yet because real-world governance often synthesizes or blurs the lines between these three groupings, they are often inadequate guideposts for what is playing out in today’s politics. Moreover, the categories themselves deserve some revision.

First, the primacists: the very classification seems like something Hubert Védrine, the former French foreign minister remembered for describing the United States as a “hyperpower,” would have formulated. But to the extent one indulges in the over-the-top, chest-thumping American stereotype that the term implies, the so-called primacists on the American right are in a different constellation than they were 20 or 25 years ago.

This is due, predominantly, to the departure of the neoconservatives from the Republican Party. Most neocons have either gone over to the Democrats altogether or are largely apolitical actors, occasionally throwing a political punch or jab, but largely confining themselves to technocratic prescriptions for the world as they see it. The halcyon days of George W. Bush’s second inaugural—with its emphasis on the advance of freedom around the world—are over. Today, most so-called “primacists” toiling away in the boiler rooms of the GOP would describe themselves simply as realists dedicated to maintaining a pro-American balance of power on both ends of the Eurasian landmass.

Second, the political foundations of the prioritizers in today’s United States are likely weaker than they appear. The arguments they have deployed in service of their position have enabled forces of restraint that will be very difficult to contain in the case of a Taiwan contingency. It would take herculean efforts to convince Americans opposed to providing security assistance to Ukraine that it is worthwhile deploying U.S. forces into a war for the survival of Taiwan. While prioritizers would perhaps join the so-called “primacists” in arguing for U.S. intervention under such a scenario, many of the supporters they have cultivated would inevitably join the restrainer school of thought.

Much like the global order, therefore, the American foreign policy community is probably best described as operating under conditions of bipolarity: realists, cast as primacists, on one side pitted against restrainers described as isolationists on the other.

Third, while restrainers have won some notable battles in the early days of the Trump administration, it would be a mistake to typecast the president himself. At heart, President Donald Trump is a populist, which, by definition, means that he is not an ideologue.

This is not to say that Trump lacks clear views. His foreign policy begins with border control, for example, where he has staked a clear stand. But Trump, if given the chance, would likely describe himself as set apart from the American foreign-policy tradition and occupying a category all his own: that of the businessman-peacemaker.

Trump sees the world through the paradigm of finance and economics. In an act of mirror-imaging, for example, Trump has built the Russians a “golden bridge” to a better economic future, as one advisor described it, if only Moscow is prepared to shut down the war in Ukraine amicably.

As an organizing worldview, this paradigm certainly has its strengths. Yet Trump might do well to heed three friendly observations on its limitations.

First, there is a greater shadow of the future in foreign affairs than there is in business. When a deal is struck in commercial real estate, the deal stands, and it’s done. By contrast, the security dilemma at the heart of international relations endures. In foreign policy, the path nations chart toward an understanding greatly affects allied and enemy behavior. This makes it acutely important to appreciate how an initiative on the global stage might shape the calculations of other nations.

Second, Trump, despite his innate toughness, may prove less inclined to draw stark red lines than some might think. In the service of delivering peace, the president is inclined to entertain compromises that would prove problematic. This posture led Trump to strike a ceasefire with the Iranian-backed Houthis that covered American vessels transiting the Red Sea without addressing the Houthis attacks on Israel, for example. It also led to rumblings before the collapse of peace talks between Russia and Ukraine that the White House would offer not only de facto, but de jure, recognition of Russia’s control over Crimea.

A third friendly observation is that because the president is so driven by commercial diplomacy, he may have less appreciation for other factors that shape the decisionmaking of adversaries like Vladimir Putin and Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. When Trump looks out at the world, the metrics that matter are trade deficits and surpluses. But America’s adversaries do not necessarily see the world in the same way and often focus more on factors like history and ideology.

To date, Trump has had notable successes where it matters most: defense spending. He has exposed America’s friends and allies in Europe to just enough hostile power to engender increased burden-sharing without going so far as to risk a security crisis on the continent. Now is the time to convert that anxiety into concrete wins.

One European ally in particular can help him do just that: the Federal Republic of Germany. Trump’s second term and German Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s coalition government will overlap almost exactly over the next four years. Both men are at the helm of new governments that are a whir of activity. Merz paid a big political price for exempting defense from the German constitutional debt brake, with up to 1 trillion euros in new infrastructure and defense spending under consideration in Berlin.

By offering consistent leadership, the Trump administration can ensure that the early momentum in defense spending, including in Germany, leads to European burden-sharing within NATO, rather than hedging behavior away from the United States.

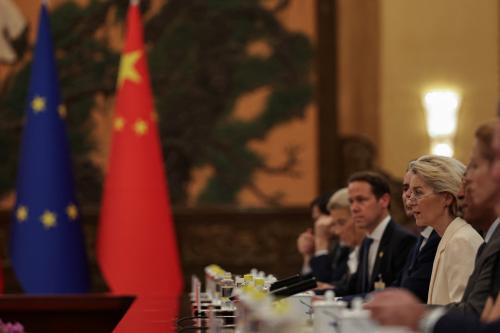

The latter would involve many fewer contracts for American defense firms, less deference to American diplomatic initiatives, and a soft European neutrality toward Sino-American competition. This would weaken Europe—but also the United States.

Of course, the United States can still rely to a certain extent on the revisionism of our opponents to help pull us together across the Atlantic. On matters of national defense, Russia (and, to a certain extent, China) will force Europe to accelerate its rearmament and buy American.

Notably, crucial capabilities that the United States currently provides cannot be duplicated in Europe quickly enough. Take air interceptors, for one: it takes far longer to produce one Aster interceptor for the SAMP/T than it does to manufacture the Patriot equivalent. Another area is software, where U.S. firms often have no European competitor. Moreover, how would Europe organize its defenses if it did go its own way? Who would command those forces, and would other countries willingly defer to a non-American commander? What happens when a cacophony of voices from smaller nations expresses different views than the larger powers do? How big should Europe be? Turkey might have the most capable military in Europe, but it’s not a member of the European Union (EU). Norway has perhaps the most fiscal space on the continent given its gas holdings. The United Kingdom, also not a member of the EU, is one of Europe’s two nuclear powers.

These are major structural issues that have not been adequately debated. The lack of resolution surrounding these topics points to the reality that Europe, for all its integrative structures, is still much more a mosaic than a unified whole.

Trump, to his credit, has catalyzed discussions and has created potentially productive anxiety. Europe is neither ready nor wanting to go its own way. But now is the time to turn anxiety into capabilities lest we run the risk of a foolish sprint to European strategic autonomy. It’s up to the United States and our allies to ensure that the scenario that prevails over the next several decades is one of transatlantic alliance.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Republican foreign policy debate, President Trump, and the transatlantic alliance

June 23, 2025