Nationally, we are in a moment of heightened political polarization around policies promoting equity and inclusion. But at the regional level, the idea that racially inclusive growth is essential to sustained prosperity is not controversial—it has become conventional wisdom among civic and business leaders. Meanwhile, spurred to action by federal economic policies, these same leaders increasingly recognize that key strategic sectors—from clean-tech to semiconductors to biotechnology—are especially critical to their region’s prosperity.

Background: Inclusive growth is now a mainstream priority in regions

These parallel movements need to be linked. Inclusive growth occurs when people of all backgrounds are not only benefiting from economic growth, but actively shaping it as owners, executives, innovators, and workers in the future industries that determine a region’s economic prospects. Yet the links between growth efforts and inclusion efforts remain weak in most regions. Locally, inclusion efforts are often disconnected from the globally competitive industries that determine a region’s economic future and provide the best jobs and wealth creation opportunities.

Inclusive growth demands business leadership and a different type of intermediary

This report focuses on the business leadership organizations—such as chambers of commerce and regional economic partnerships—that can, and must, create this linkage. These organizations are essential because inclusive growth depends on businesses in key industries being organized to send clear signals about their demand for skills and inputs so the public and civic sector can confidently invest in preparing people for those opportunities. And business leaders need to be organized so they can receive signals from the surrounding communities that shape their own competitiveness, and adapt their firms’ practices to better draw on overlooked workers and small business owners in their home regions.

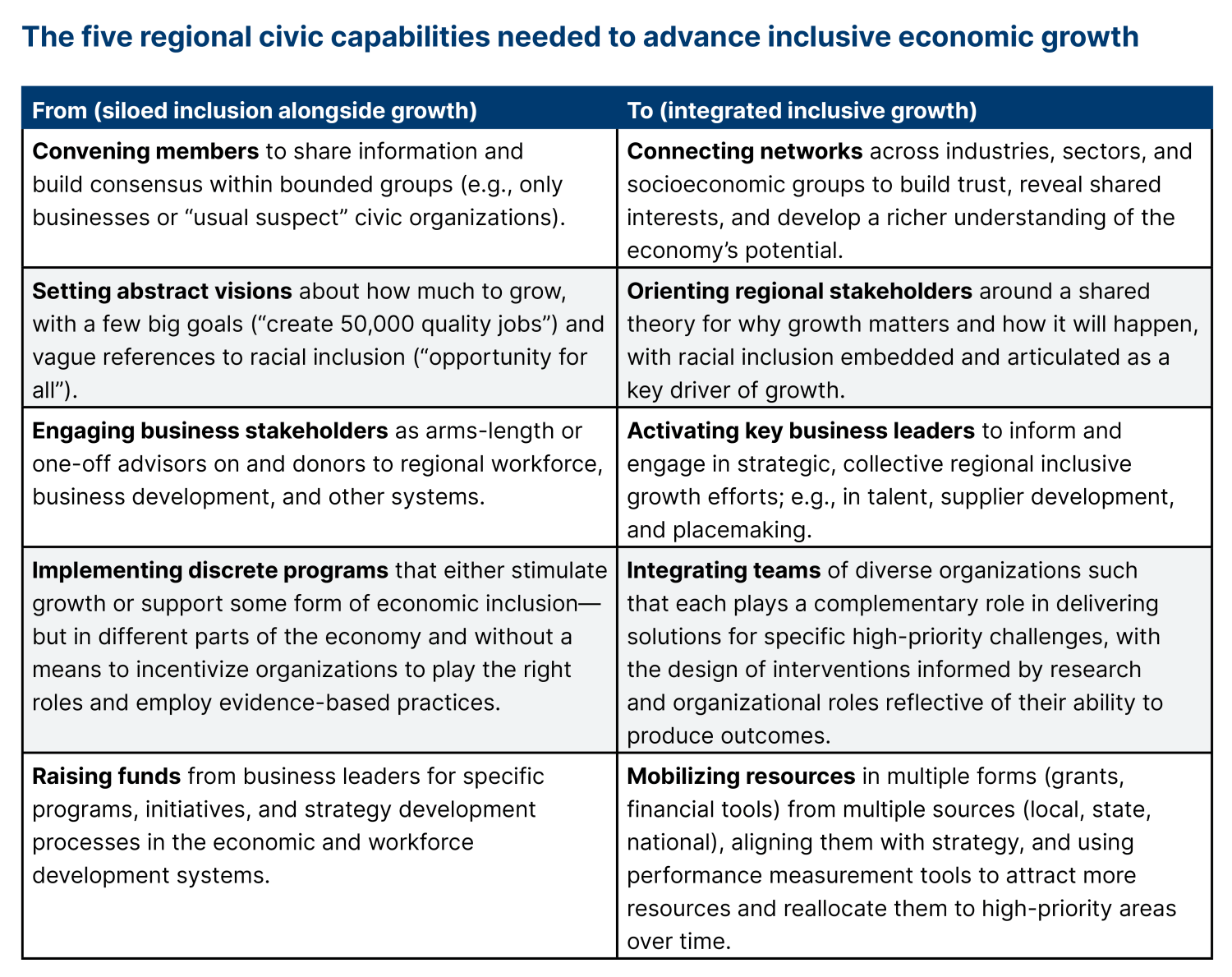

Orchestrating this type of cross-sector interaction is more important and more difficult than is generally understood. The work is often referred to as “convening,” and these organizations are called “intermediaries.” These terms suggest that what’s needed is neutral dot-connecting, when in fact what’s needed is purposeful creation and management of civic networks in service of a shared economic strategy. Without a clear definition of what this work involves and why it matters, the field will continue to underinvest in the foundations of inclusive growth in favor of narrow programmatic efforts in which businesses rarely engage fully as informants and investors.

To address this gap, this report defines five regional capabilities that comprise the “invisible civic infrastructure” that enables racially inclusive economic growth. Drawing on insights and case studies from eight diverse business leadership organizations that formed Brookings Metro’s Regional Inclusive Growth Network, the report articulates why these organizations need to invest in these capabilities and why it is hard to do so. In summary, the report provides a practical framework for shifting from a siloed approach to an integrated one for inclusive growth.

Corporate, government, civic, and philanthropic leaders can use this framework to assess and strengthen the capabilities of business leadership organizations in their regions. Our hope is that this report allows organizations building the necessary capabilities to be recognized and supported for doing so, creating pressure for others to raise to the bar too, and ultimately enabling more regions to achieve truly inclusive economic growth.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) made this project possible, and we are particularly grateful to James Hardy and Chloé Nuñez at RWJF for their ongoing support and guidance. We are indebted to Francie Genz and Amy Liu, whose work informed this report, and whose thoughtful review of earlier drafts substantially refined our writing. In addition, we’d like to thank the following individuals for helpful feedback on earlier drafts: Brian Anderson, J.W. Carpenter, Megan Crook, Brendon Cull, Curtis Hollis, Christina Mastroianni, Lakesha Mathis, Lia McIntosh, Pete Metz, Steve Millard, Judy Reese Morse, Charles Phipps, Stacey Robles, Consuelo Ross, Brandon Rudd, Jenae Sikkink, Tiffany Tauscheck, Audrey Treasure, Jennifer Wakefield, and Tyronne Walker. We’re grateful to participants in the Regional Inclusive Growth Network, who helped inspire and sharpen this report. All remaining errors and omissions are the sole responsibility of the authors.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).