On June 4, the Center on the United States and Europe hosted the 20th annual Raymond Aron Lecture featuring keynote remarks from Camille Grand, distinguished policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. This is a lightly edited version of Grand’s delivered remarks. Additional responses from discussants Mara Karlin and Peter Rough are also available.

In the preface to the U.S. edition of his 1973 “contemporary history” essay, “The Imperial Republic: The United States and the World 1945-1973,” the French philosopher and foreign policy commentator Raymond Aron suggested that U.S. foreign policy might be entering a different era under President Richard M. Nixon. He noted:

“The United States’ rapprochement with its enemies (the Soviet Union and Communist China), trade and monetary disputes with its European and Japanese allies, the narrowing of the gap between the wealth of the United States and that of its partner-rivals, the revolt of the Senate against the President’s omnipotence, the massing of public opinion against the imperial burden, and the arraignment of those who had been responsible for the war in Vietnam.”

Any resemblance with current events (with the possible exception of the Senate revolt) is no doubt entirely fortuitous. More seriously, this description of the post-Vietnam moment in U.S. policy offers an interesting echo to the current foreign and security policy debate.

The modern relevance of “The Imperial Republic”

Aron’s conceptual argument in this essay is that U.S. foreign policy as it emerged after World War II, defined as the “imperial republic,” is unique and distinct from traditional forms of empires and imperialism, but also that it could be a parenthesis in U.S. foreign policy.

As noted by Irving Horowitz in the introduction to the latest republication of Aron’s essay, “the present-day linkage of the two words: ‘imperial’ and ‘republic’, while quite clever, tends toward ambiguity.” It is therefore important to unpack Aron’s reasoning behind these terms. Refusing to adopt the popular concept of an “American empire,” Aron above all distinguishes the American “imperial republic” from more traditional forms of imperialism (including colonialism), suggesting a more benevolent form of imperium.

Aron opens his essay by noting that, in the late 1940s, “commentators were noting that for the first time in history a republic had risen to the first rank without ever aspiring to the glory of dominion. As the price of its victory, it had to take half the world in charge, guarantee the security of Europeans too weakened to defend themselves unaided, and concern itself with whole areas of the globe that were on the point of lapsing into chaos.” He further divides “the diplomatic history of the United States into three main periods: the first dating from 1783 to 1898, from the Treaty of Paris to the war with Spain; the second from 1899 to 1941 (or 1947); and the third, which begins with Pearl Harbor or the Truman Doctrine (March 1947),” and stresses the key elements of the first two periods:

“Taken as a whole, each of them contrasts with the other in essentials. Whereas the movement of ideas and events from the end of the eighteenth century to the end of the nineteenth leads to a system devised and purposed by the Founding Fathers, a sovereign republic covering the greater part of North America, hence geopolitically insular—from the end of the nineteenth century onward the observer can discern neither the logic of the plot nor the aims of the actors. By the end of the last century the national purpose of the founders of the American republic had been achieved. Throughout the ensuing half-century, the republic searched anew for a purpose and swung from one line of conduct to the other as whim dictated.”

Aron captures well the essence of pre-1941 U.S. foreign policy as seen by Europeans when he further notes that:

“The insular power whose territory was sheltered from attack and which sent expeditionary forces to distant lands preserved—until 1945—the strange privilege of profiting politically from its errors. By its abstention, by spreading the illusion that it would continue to remain aloof from hostilities in Europe, by its inability to choose between compromise with Japan and a determination of which massive rearmament alone would have given convincing proof, the United States historically bears some of the responsibility for the outbreak of the twofold war in the Atlantic and the Pacific.”

From his perspective, “the quarter-century of preeminence was the sanction—whether reward or punishment—of what everyone today calls an aberration in that a great power upset the system quite as much by its refusal to assume its due rank as by pride of primacy.”

Today as in 1973, quoting Aron’s essay again, “Europeans are once more beginning to fear this refusal after denouncing that pride.”

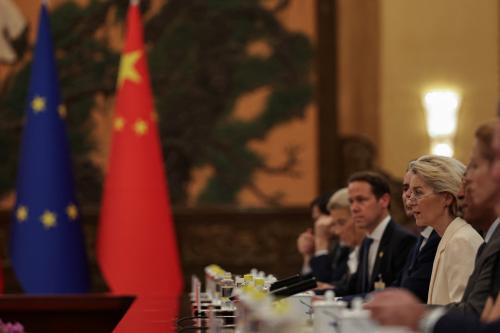

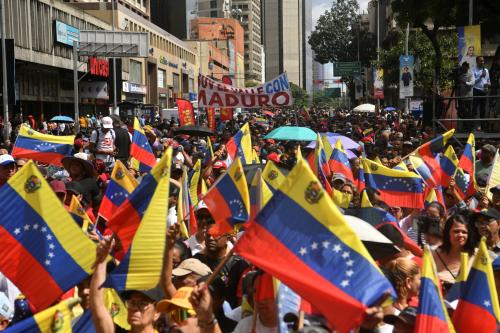

President Donald Trump’s foreign policy, too, seems to oscillate between the three Republican tribes described by my European Council on Foreign Relations colleagues Majda Ruge and Jeremy Shapiro: “restrainers,” “prioritizers,” and “primacists.” The rather traditional isolationism endorsed by the “restrainers” aims at limiting U.S. engagements and presence abroad through burden sharing/shifting and a strong reluctance to take part in new conflicts after decades of costly wars overseas and entangling alliances in Europe and Asia. A consistent variant of this trend is the new (but very 1898) “hemispheric imperialism,” with its emphasis on the need to control or acquire territory in the Western Hemisphere, like Greenland, Canada, and Panama. The “prioritizers” focus on the Indo-Pacific and view China as the critical challenge, whereas traditional “primacists” argue for continued U.S. global leadership. It is clear that the president’s instincts, as well as the views of many senior figures in the cabinet and senior national security leadership, are moving away from this third view (even if Trump is not consistently aligned with one tribe). This suggests that the Europeans are right to express concern at a profound shift in U.S. foreign and security policy closing a long chapter opened in 1941, as already foreseen by Aron in 1973.

It is also probably fair to note that, notwithstanding the policy and rhetoric of Trump and his administration, these trends affecting European security are older and their roots go much deeper and broader. The United States faces many challenges, the burden-sharing debate is almost as old as NATO, the pivot to Asia has been on the table at least since the Obama administration, and the public fatigue with “forever wars” goes well beyond the MAGA base.

In this context and to refrain from lecturing further on U.S. foreign policy in Washington, it seems appropriate to break down scenarios for the future of transatlantic relations and the associated challenges for the Europeans in this emerging new era.

Four scenarios for the future of transatlantic relations and NATO

As the debate crystallizes on the eve of the Hague NATO summit, four hypotheses are taking shape, all of which point to a NATO 3.0 that bears little resemblance to the NATO 1.0 of the Cold War or the NATO 2.0 of the post-Cold War era: a NATO that is less American, fundamentally moving away from some of the core elements of the “imperial republic” as defined by Aron.

The first scenario is an organized transition to a more European alliance. In this scenario, the Europeans continue to increase their defense spending and work closely with the United States to build an alliance that is less dependent on American conventional resources, but without calling into question American commitment and especially the extended American nuclear deterrent. At the end of a coordinated evolution, probably spreading over a decade, NATO has become more European with a strong European pillar, and a significant portion of the burden has been transferred. The European Union (EU) plays a more important role even if the United States remains committed to European security and the U.S. military presence in Europe endures.

In the second scenario, this transition occurs in a chaotic way, through a succession of crises and brutal unilateral decisions. The United States decides to withdraw troops and resources without serious consultation and further signals a reduction in its interest in the Euro-Atlantic theater, undermining European security and, no doubt, forcing the Europeans to move forward at breakneck speed. Such an evolution could be imposed by a major crisis in Asia or unfavorable American trade-offs between various theaters (Indo-Pacific, Middle East, and the Americas) at the expense of Europe. Even if the outcome is more or less comparable to the previous case, this chaotic scenario is not without risk for the alliance. In addition to inevitable internal political tensions, this scenario generates moments of strategic vulnerability during the transition phase. Indeed, it becomes tempting for NATO’s adversaries, led by Russia, to test the solidity of the alliance and the robustness of Article 5 in such a scenario, for example by multiplying hybrid attacks or conducting a limited operation against a Baltic state.

In the third, more radical scenario, an American administration, maybe frustrated by the lack of European progress—whatever the reality of that progress—and determined to reduce American commitments, pushes a withdrawal from European affairs (with or without priority given to Asia) to its logical conclusion. The logic is one of radically reducing American participation in NATO and presence in Europe, even without effectively withdrawing from the Washington Treaty. In practice, and within the space of a few months or years, the United States would multiply the signals of disengagement: abandonment of Ukraine; rapid, massive, and uncoordinated troop withdrawals; closure of American bases in Europe; disinterest in NATO’s command functions; and a possibly irreversible weakening of the American guarantee in the eyes of allies and foes. In this scenario, Europe would be entering territory uncharted since 1949: having to organize the defense of Europe without the United States, with painful choices to be made about the scale of the military effort and priorities, the need to urgently fill capability gaps, and the terms of a collective defense not based on an American guarantee that had become uncertain at best. At the same time, some allies will be tempted to seek alternative security guarantees, be they bilateral or minilateral arrangements, or even compromises with Moscow. Given the Russian perception of NATO as an essentially American-led alliance, the risk of a test of European solidarity and NATO’s ability to react without American resources would be high. This scenario is the one Aron was concerned about when he feared a return to pre-1941 isolationism. From a European perspective, it would put an end to a cycle opened in the late 1940s that French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman described on the eve of the signature of the Washington Treaty: “We obtain what we had hoped for in vain between the wars: that the United States recognizes that there is neither peace nor security for America if Europe is in danger.”1

Fourth and the most extreme scenario: a hostile United States. In this scenario, still unlikely, transatlantic conflicts over trade, technology, or democratic values, and a form of quid pro quo with Moscow over critical issues such as Ukraine, sanctions, or disarmament, lead to a historic break-up of the Western family that goes far beyond the traditional burden-sharing debate. In an extreme variant, American ambitions in Greenland take the form of military pressure, generating an unprecedented crisis in the alliance.

At this stage, it should be noted that the Trump administration’s formal declarations seem to rule out scenarios three and four. But the first scenario of an orderly transition seems neither guaranteed nor automatic, even though the NATO secretary general and many allied leaders are trying to build a shared and convincing narrative combining a case for a renewed transatlantic bargain and new ambitious defense spending targets. The key anticipated Hague summit deliverable is a commitment for allies to spend 5% of their GDP on defense (consisting of 3.5% on core defense spending and 1.5% on broader security-related investments). It is also clear that the U.S. permanent representative to NATO, Ambassador Matthew Whitaker, has already publicly announced a debate on the reduction of the U.S. military footprint after the NATO summit as part of the broader revision of the U.S. force posture, confirming in unequivocal terms previous statements by U.S. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth. As Hegseth told the Ukraine Defense Contact Group in February 2025, “The United States will no longer tolerate an imbalanced relationship which encourages dependency. Rather, our relationship will prioritize empowering Europe to own responsibility for its own security.”

It seems certain at any rate that the status quo—a sort of business-as-usual “scenario zero”—will not be acceptable to the United States, and that Europe must prepare to defend itself with less America, or even without America as a first responder, notwithstanding the fact that some European allies still fear a “self-fulfilling prophecy” and that they will not be in a position to cope with the strategic consequences of a radically new situation. In short, Europe still hopes to preserve the first scenario, while the Trump administration seems to be wavering between pressuring the Europeans to make a fundamental adjustment (scenario two) and a more radical move (scenario three).

Four challenges for Europe

In this context, Europe must now address several security challenges. The good news is that the blueprint is largely the same whatever the scenario and that there is a path to defending Europe with less America. It is demanding and somewhat costly but can be achieved within a decade or less if four challenges are properly tackled.

- Building a European ability to defend Europe with less (or no) America: “A Plea for Decadent Europe” (to quote another Aron book).

The blueprint is pretty well identified. My July 2024 paper for the European Council on Foreign Relations “Defending Europe with less America” offers a to-do list for remedying shortfalls. A recent paper for the International Institute of Strategic Studies, “Defending Europe without the United States,” estimates that $1 trillion in European military investment will be needed to address the gaps associated with the objective stated by Hegseth that European allies should take primary responsibility for defense of the continent—or in other words, that conventional defense of Europe would be the responsibility of the Europeans. This requires rebuilding mass and readiness to enable the Europeans to provide the “cavalry” in the event of a crisis or conflict and, at a minimum, to be the first respondent with some robust capabilities. It also requires addressing specific capability gaps, with a focus on critical enablers and high-end strategic capabilities (intelligence, space, and reconnaissance assets, including long-range unmanned aerial vehicles, space capabilities, airborne surveillance, strategic airlift and air-to-air refueling, and more broadly military mobility enablers, electronic warfare, air and missile defense, as well as conventional deep precision strike capabilities). The EU can help to move this agenda forward faster and contribute to funding the effort. This agenda is extremely demanding but, with proper funding over a decade, it is not out of reach:- NATO Europe and Canada spent $250 billion per year on defense more than a decade ago and now spend $430 billion per year; if indeed, defense spending continues to grow from a 2.1% median to 3.5% of GDP, it will generate much more than an additional trillion total over the next decade.

- The European defense industry has been gradually moving into war mode and is capable of delivering most of the capabilities needed; it benefits from a new focus and support from the EU and its member states. The European civilian defense and aerospace industry is already very competitive, so there is no reason whatsoever that Europe could not deliver a large portion of the needed capabilities, when U.S. industrial capacity is also overstretched.

- European civilian and military leaders have now—finally!—understood that waiting for the United States to go back to its previous posture was not a plan and have given up the poor policy of entertaining severe dependencies to keep the United States on board. They now seem ready to move at pace, even if there are massive differences in the European landscape between those already there in terms of level of fiscal effort (Poland and the Baltic states), those getting there fast (Nordics, Germany, the Netherlands), those convinced but struggling with fiscal constraints (France, the United Kingdom, Greece) and those who were still hoping to dodge having to make an effort significantly above 2% soon (Spain, Italy, Belgium). Days before the summit, there are very few holdouts declining to subscribe to the new 5% pledge, combining 3.5% on core defense spending and 1.5% on related security investment.

- Preparing and deterring extreme scenarios for European security: time for another “great debate” (to quote Aron’s 1963 book on nuclear strategy)

The major difference between defending Europe with less America or without America is the need to address the most complex gaps: extended nuclear deterrence and access to exquisite U.S. intelligence. The current open questions regarding the scope and robustness of the U.S. security commitment to Europe make it imperative to address these issues and to develop mitigation strategies:- A new once-in-a-generation European “great debate” is emerging on the nuclear front—as it did before in the late 1940s to establish the principles of nuclear deterrence, in the early 1960s to take into account the new U.S. vulnerability to Soviet intercontinental ballistic missiles and establish the NATO nuclear sharing arrangements, and in the late 2000s to review the role of nuclear weapons between calls for abolition and renewed proliferation. President Emmanuel Macron’s repeated statements since 2020 on the “European dimension” of France’s vital interests, the K.’s looking into rebuilding an air component to its own deterrent, the German chancellor calling for a European conversation, Poland openly discussing a national nuclear option: all these show that the debate is no longer confined to experts’ circles. The terms of the challenge are known. But the debate needs to take place in an orderly fashion: with the United States making clear the robustness and level of its nuclear commitment in a new environment; with France and the U.K. reviewing their roles, positioning, and capabilities to contribute more; and with the non-nuclear allies exploring how they can contribute more via nuclear (dual-capable aircraft) and non-nuclear (conventional deep strike, missile defense) means. The changes ahead might be limited or more fundamental, but they need to happen.

- The intelligence-sharing conversation is in some ways even more complex given the various existing formats (bilateral, Five Eyes, NATO) and certainly more discreet. But it is equally important for Europe to reduce its dependency in this field and for both sides of the Atlantic to understand how intelligence sharing will continue or not, including in the context of Ukraine. This requires Europe, among other things, to develop more space-based and cyber capabilities.

- Securing the future of Ukraine and thus of Europe with less (or no) America to avoid another century of “total war.”

There is a strong feeling in Europe that war is back. For many Europeans, Ukraine is not another regional conflict to be stopped or not. As Europe wants to avoid what Aron called “Les guerres en chaîne” (the French title to his 1948 book, titled “Total War” in English, which described the chain of global conflicts in the first half of the 20th century), it needs to develop its own strategy to secure the future of Ukraine and thus the future of European security (combining continued assistance, inclusion in European security institutions, and a post-ceasefire European reassurance force).

- Reinventing post-“imperial republic” alliances and institutions.

NATO 3.0 is likely to be very different from Cold War NATO 1.0 or post-Cold War NATO 2.0. Hopefully, it will still be a solid transatlantic alliance, but it will also have a much stronger European pillar, making it more balanced and less American. This requires not only the Europeans to spend more but also the United States to accept “letting go” in a new transatlantic bargain, as we argued in a recent report on the future of the transatlantic alliance from a Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs task force which I co-chaired. But this ideally requires a structured and honest conversation to develop a shared vision and plan to build a new transatlantic alliance. The Hague NATO summit and its aftermath will prove whether such a conversation is possible and if both sides of the Atlantic can engage in good faith to define jointly the terms of such a bargain.

Conclusion

Europeans probably need to assume that the end of the “imperial republic” is happening. It might be a lasting development, fundamentally transforming European security and transatlantic relations; it could also be a moment in a cycle. After all, the “imperial republic” survived for 50 more years after Aron’s 1973 book questioning its ability to endure. There is nevertheless no doubt that the current foreign and security policy moment goes beyond the current administration’s state of mind and that today’s trends are likely to last.

We can hope that there is a path to a renewed, more balanced transatlantic alliance, a NATO 3.0 in which the United States would remain engaged and value its allies. Europeans must also prepare for more complex scenarios—for which Aron’s work offers an extraordinary toolkit. His writing, including “The Imperial Republic,” exemplifies the type of rigorous analysis that can help us think through these challenging times.

-

Footnotes

- Quoted in Alfred Grosser, Affaires étrangères. La politique de la France, 1944-1984 (Paris: Flammarion, 1984), 75-76.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The end of the “imperial republic” and the future of the transatlantic alliance

June 23, 2025