Nigeria’s recent announcement confirming that it is closing its borders to prevent movement of all goods has been met with harsh criticism from neighbors and regional integration advocates. The Buhari administration has justified the decision as a tactic to curb smuggling of goods of which the country wants to internally increase production, such as rice.

The border closures will have particularly negative consequences for traders, especially informal ones, along the Benin-Nigeria border, as the two economies are closely intertwined.[1] Indeed, this informal trade generates substantial income and employment in Benin, and Benin’s government collects substantial revenues on entrepôt trade—goods imported legally and either legally re-exported to Nigeria, or illegally diverted into Nigeria through smuggling.

The informal sector throughout West Africa, and particularly in Benin, represents approximately 50 percent of GDP (70 percent in Benin, in fact) and 90 percent of employment. Unsurprisingly, informal cross-border trade (ICBT) is pervasive and has a long history given the region’s artificial and often porous borders, a long history of regional trade, weak border enforcement, corruption, and, perhaps most importantly, lack of coordination of economic policies among neighboring countries. Notably, ICBT takes several forms, not all of which are illegal: For example, trade in traditional agricultural products and livestock in bordering countries may involve little or no intent to deceive the authorities, as peasants and herders ignore artificial and un-policed borders.

The economic relationship between the two countries, both members of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), is already asymmetric, with Nigeria exerting much more influence on Benin than vice versa. Given Nigeria’s larger population, economy, and natural resource wealth, Benin has adopted a strategy centered on being “entrepôt state,” i.e., serving as a trading hub, importing goods and re-exporting them legally but most often illegally to Nigeria, thus profiting from distortions in Nigeria’s economy. Benin’s dependence on Nigeria is not apparent from official trade statistics, as Benin’s reported trade with Nigeria accounted for only about 6 percent of Benin’s exports and 2 percent of Benin’s imports in 2015-17.[2] These official statistics are very misleading, however, as they do not reflect the vast informal trade along the border.

Nigeria’s trade policies create distortions that incentivize smuggling

Nigeria’s heavy dependence on oil and many dysfunctional economic policies have created an environment for ICBT between it and its neighbors, mainly Benin and Togo, to flourish. The wide gap between the official and black-market rates of the naira; Nigeria’s subsidized fuel prices; import barriers (Table 1); poor trade facilitation (Table 2); and Benin’s poor business climate have incentivized local traders to turn to the informal cross-border trade.

Table 1: Nigeria’s import barriers on selected products, import tax rates (%), and import bans, 1995-2018

| 1995 | 2001 | 2007 | 2013 | 2018 | |

| Beer | Banned | 100 | Banned | Banned | Banned |

| Cloth and apparel | Banned | 55 | Banned | Banned | 45/ Forex ban** |

| Poultry meat | Banned | 75 | Banned | Banned | Banned |

| Rice | 100 | 75 | 50 | 100 | 70*** |

| Sugar | 10 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 |

| Cigarettes | 90 | 80 | 50 | 50 | 95 |

| Used cars* | Banned | Banned | Banned | Banned | Banned / 70 |

| Vegetable oil | Banned | 40 | Banned | Banned | Banned |

*The maximum age of cars banned from import has varied over time as more 8 years old in 1995, and 5 years in 2001, back to 8 years in 2007, and 15 years in 2018. In addition, imports are banned via land borders since 2016.**Banned from using the official foreign exchange market. ***Rice imports banned through land borders since 2013.

Sources: Soulé (2004), Nigerian customs data provided by the World Bank, Nigerian import prohibition list https://www.customs.gov.ng/ProhibitionList/import.php, online reports, World Trade Organization Nigeria Trade Policy Review 2017.

Table 2: Indicators of trade facilitation, Benin and Nigeria, 2018

| Trading across borders: overall rank (190 countries) | Time to import: border compliance (hours) | Time to import: documentary compliance (hours) | |

| Benin | 107 | 82 | 59 |

| Nigeria | 182 | 264 | 144 |

Source: World Bank Doing Business Indicators 2018.

Magnitude of entrepôt trade between Benin and Nigeria

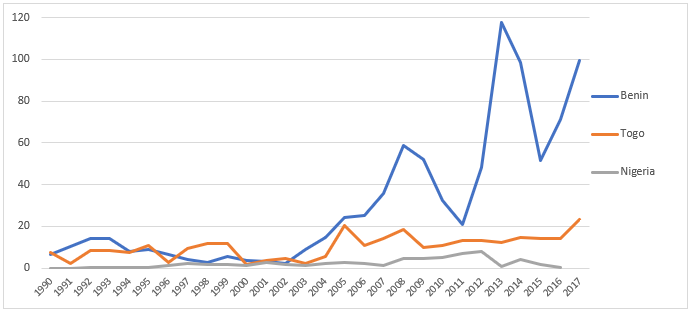

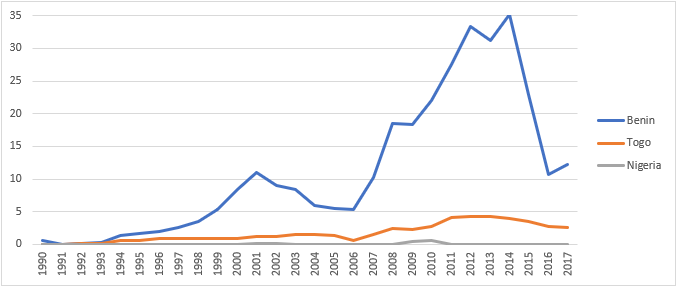

Smuggling is, of course, difficult to measure but can be estimated indirectly through the magnitude of official imports per capita into Benin compared to Nigeria and other countries. Imports per capita into Benin of certain products—such as cars, cloth, rice, and poultry, all heavily protected in Nigeria—are far too large to be explained by Benin’s domestic consumption (Figure 1 a-b).

Figure 1. Imports per capita for Benin and Nigeria, USD

A. Rice

B. Poultry

Effects on national income, employment, and tax revenues

Like in other countries, the effects of ICBT for Benin are mixed. For example, ICBT generates about 20 percent of Benin’s GDP. Moreover, gasoline smuggling employs around 40,000 people, about as much as the size of the public sector in Benin, while direct and indirect jobs from used car smuggling are estimated at around 15,000 and 100,000 people, respectively. On the other hand, the longer-term effects on economic growth and diversification can be negative: ICBT attracts entrepreneurial talent into illegal or semi-legal informal activities instead of potentially more productive sectors. Furthermore, the implication of government officials at all levels of informal activity makes reform much more difficult.

Benin’s system of import taxation has revolved around maximizing the income from entrepôt trade, by taxing goods when they enter Benin at a rate well below that in Nigeria or taking advantage of Nigeria’s import prohibitions. The country’s revenues are hit hard when there are border closures or there is a recession in Nigeria due to lower demand for products being traded there.

Policy recommendations

Given the sheer number of people engaged in cross-border trade and deriving their livelihoods from it on both sides of the border as well as the ineffective policing of that trade, the success of its closure is up for debate. On the other hand, the importance of powerful interest groups controlling this very lucrative business on both sides of the border, especially in Nigeria, is likely to make this policy even less effective, as past failures of these closures widely illustrate. In addition, closing borders with a neighboring country sharing a common external tariff and a soon-to-be implemented common currency might not be the right signal to send about the seriousness of the West African integration agenda of which Nigeria has become a prominent advocate. It is clearly not in Nigeria’s interest to pursue policies of relying on import protection to boost inefficient domestic industries and subsidizing gasoline use. Instead, the solution to the overarching enigma of its weak industrial and agricultural bases might be in the predominance of the oil sector over the rest of the economy (oil makes up 90 percent of its exports), as well as counter productive economic policies and rampant corruption and favoritism. Making bold steps towards diversifying the economy away from natural resources and agriculture, by implementing more market-friendly measures, and relying less on discretionary ones such as border closures, might be the right move to make.

At the same time, while Benin’s combination of formal and informal institutions supporting entrepôt trade are quite sophisticated and effective in their objective of promoting Benin as an informal trade hub, its development policy oriented towards informality and smuggling is unsustainable. Benin should take measures to improve the business environment for legal businesses. At present, Benin’s trade facilitation institutions and business climate are sufficiently superior to Nigeria’s to circumvent Nigeria’s trade barriers, but inadequate for serving as a regional service center for legal trade and facilitating foreign and domestic investment. Recommended policies include: modernization of customs, using more information technology and formal management procedures that improve accountability and transparency; improved port logistics; and linked rail and road infrastructure investments. More broadly, Benin needs to upgrade its institutions to boost investment in productive activities.

For more on the complex issues surrounding informal cross-border trade between Nigeria and its neighbors, see Stephen S. Golub and Ahmadou Aly Mbaye’s paper, Benin – The economic relationship with Nigeria.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The effects of Nigeria’s closed borders on informal trade with Benin

October 29, 2019