Last week, we covered what’s brought us to the current budget quagmire between Congress and the president. How might they get out of it? Here’s an overview of one route to a grand bargain:

First, a temporary package.

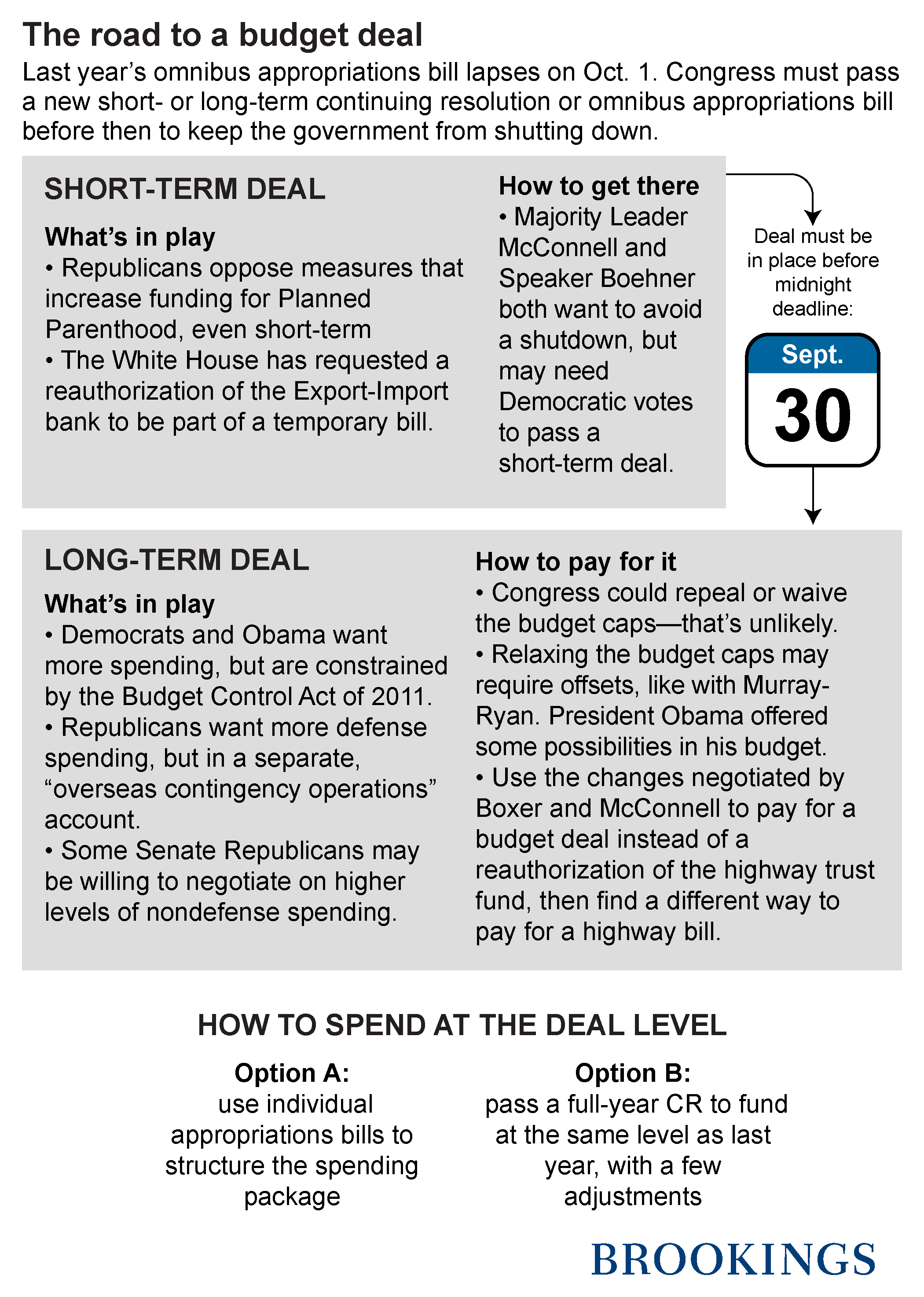

The 2016 fiscal year begins on October 1. A short-term deal between Congress and the president is necessary to keep funds flowing many federal programs, including defense, education, housing, foreign aid, and scientific research.

What’s in play?

Republicans in both the House and Senate have threatened to hold up a temporary funding resolution over Planned Parenthood. An effort to this in the Senate in August failed, but at least 31 House Republicans have promised to oppose any appropriations measures, even short-term ones, that include funds for the organization. The White House, for its part, has requested that a temporary bill include a reauthorization of the Export-Import Bank, which has been a flashpoint within the Republican Party of late.

What’s the way out?

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell is on record saying he has no interest in a shutdown, having learned from 2013’s experience. One key difference: his caucus now includes four senators running for president, all of whom have displayed a taste for procedural warfare to achieve political goals. So far, McConnell’s counter-maneuvers have prevented these efforts from becoming anything more than temporary headaches, but they could return during debate over a short-term measure.

House Speaker Boehner also wants to avoid a shutdown, which may require him to break the so-called “Hastert Rule.” As my colleague Sarah Binder has written about here, here, here, and here, the Speaker has a history of approving must-pass bills with a coalition that combines a minority of his own caucus with Democrats, including on the deal to reopen the government after 2013’s shutdown. Passing a short-term funding bill may require a similar effort.

Next, the framework for a longer-term deal.

What do both sides want?

Obama and congressional Democrats want to spend more on both defense and non-defense discretionary spending, but they are constrained by the caps enacted under the 2011 Budget Control Act. The president’s budget proposed $38 billion more in defense, and $37 billion more in non-defense, than would be allowed under the BCA caps. The budget blueprint authored by congressional Republicans and passed in May also requests more for defense, but accomplishes that by stashing the amount over the limits in a special account for “overseas contingency operations” that doesn’t count against the caps.

Is there room for compromise?

Several Republicans in the Senate—including McConnell—have indicated a willingness to negotiate over higher levels of non-defense spending, as reflected in the inclusion of a Senate “deficit neutral reserve fund” targeted at cap relief in this year’s budget resolution. Reserve funds, an increasingly common feature of the budget, have a narrow technical purpose but serve as important signals about the sense of the Senate—in this case, that a deal on both kinds of spending might be possible. This stands in contrast to the House, where the cap relief reserve fund covers only defense spending and requires that any increases in the defense limits must be paid for in separate legislation, making it more difficult to logroll the measures together.

How to pay for it?

At its heart, the question of “paying for” any changes to the BCA’s caps is a political one. Congress could pass, and the president could sign, legislation that repeals the caps altogether. The procedures that are in place—and there are many—to enforce other budget rules can be waived. In the House, this is usually done through the special rule governing debate on the underlying bill, passage of which requires a simple majority. In the Senate, waiving the rules generally requires 60 votes—but so will any legislation of as much consequence as a budget deal. Put differently, if 218 House members and 60 senators want to change the BCA’s spending limits, other existing budget rules won’t necessarily stand in their way. (See, for example, the Senate’s willingness to waive a point of order against increasing the long term deficit in this spring’s ‘doc fix’ bill.)

That said, if the 2013 Murray-Ryan deal is any indication, relaxing the BCA’s caps, even temporarily, will require offsets. From where might these come? Some possibilities come from the president’s budget submission, including $48 billion from reducing premiums for crop insurance, increases in TSA passenger fees, allowing the FCC to implement new fees, and limiting the amount individuals can put in tax-protected retirement accounts. An extension of Medicare changes—such as increasing premiums for high-income beneficiaries—that were partially implemented as part of the ‘doc fix’ bill could generate another $96 billion.

Another option involves turning to roughly $40 billion in changes that were negotiated by McConnell and Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-CA) to partially pay for the Senate-passed reauthorization of the Highway Trust Fund. These include stepping up IRS enforcement using private collections agencies, indexing customs user fees to inflation, selling oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, increasing mortgage guarantee fees, and reducing the dividend rate paid by the Fed to large member banks on their paid-in capital.

If the highway offsets are on the table for a budget deal, though, Congress will need a different set of changes to accommodate a permanent highway measure, which is estimated to cost $45 billion for a three-year bill or $90 billion for a six-year version. How to do that? Enter tax reform. Key House members, including Ways and Means chairman Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI), have indicated an interest in a six-year highway bill that’s paid for with changes to the U.S.’s international taxation system. Ryan’s approach has several other key proponents, including Senators Rob Portman (R-OH) and Chuck Schumer (D-NY), but McConnell remains unenthusiastic.

Using a tax bill to offset highway funding could be further complicated by the so-called ‘tax extenders’—provisions benefitting individuals and businesses that are only enacted for a year or two at a time. Some, including Senate Republican Conference chairman John Thune (R-SD), have suggested tackling the extenders in conjunction with the highway bill. This would likely make the bill more palatable to members of the GOP, but would also reduce the amount of savings in the overall tax package.

Finally, how to actually spend at the agreed-upon levels.

If Congress and the president agree on the framework for a deal, they still have to decide on how much to spend on various government programs for the next fiscal year—and, importantly, how to structure that package.

There are two basic approaches to a massive, late-in-the-year funding measure—with room to split the difference between them. One is to use the individual appropriations bills developed by the House and Senate appropriations committees as the basis for an ‘omnibus’ or ‘consolidated’ appropriations package. Last year’s “Cromnibus” generally embodied this approach, building on 11 of the 12 standalone bills worked on during the year.

The second approach is to pass a full-year ‘continuing resolution,’ or CR. A CR generally continues funding at the same level as the previous year, with adjustments by a flat-percentage formula or individualized exceptions (called ‘anomalies’). Congress took something more akin to this approach in 2011, when only the Department of Defense was funded through a regular measure.

Reports suggest a full-year CR is a distinct possibility for 2016—much to the chagrin of agencies across the federal government. From a management perspective, CRs make it more difficult to hire new staff since “new activities” are usually prohibited, delay procurement and training, and leave everyone with less time to spend the funds eventually allocated. Moreover, research by Dan Carpenter shows that shifts in budgets are powerful signal by which Congress and the president transmit information to agencies—information that can get lost with long-term CRs.

Given the number of moving parts in play here, it’s clear that the process to a grand bargain is a tricky one. Both sides have options, but it remains an open question whether they’ll use them—and whether they will do so before mid-November or early December the debt ceiling enters the equation once again.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The budget showdown: How do we get there from here?

September 21, 2015