The official federal budget outlook has deteriorated dramatically since early 2001, due to last year’s tax cut, the economic slowdown, and the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. The official projections, however, are overly optimistic. In addition to the pressures from the long-anticipated increase in entitlement spending as the nation ages, the government now also faces growing spending needs for defense and homeland security. These trends imply that future taxes must rise, future spending outside of defense and the elderly must decline, or obligations to the elderly and to defense be reduced.

Faced with these constraints, the Bush administration proposes reduced spending for low-income households and substantial increases in federal borrowing. But rather than propose higher taxes or even reconsider some of the cuts passed last year, the administration advocates substantial new tax cuts, including making the 2001 tax cut permanent. The proposed tax cuts disproportionately benefit high-income households and would significantly worsen the budget outlook. A more responsible fiscal policy would freeze the tax cut at its current level, which would save enough revenue, relative to a permanent extension, to keep Social Security solvent through 2075. Strictly following the letter of the law and allowing the cuts to expire as scheduled in 2010 would save twice as much revenue over the same period.

POLICY BRIEF #100

The Ten-Year Budget Outlook

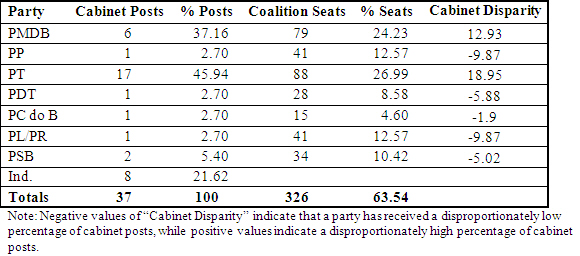

Between January 2001 and January 2002, the ten-year unified surplus projected by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) fell from $5.6 trillion to $1.6 trillion (see table 1) for the 2002-2011 period. The decline is concentrated almost completely in the non-Social Security part of the budget, which fell from a projected surplus of $3.1 trillion in January 2001 to a projected deficit of $0.7 trillion by January 2002. About 40 percent of the shift is due to last year’s tax cut (the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001, or EGTRRA), another 40 percent arises from economic and technical changes in the forecast, and the remaining 20 percent is attributable to increased spending, primarily defense and homeland security outlays in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks.

These official forecasts are constructed according to a variety of statutes that are intended to provide a neutral benchmark against which proposed legislation can be measured. But the rules employed may not be the most useful or appropriate way to gauge the government’s fiscal condition—or to estimate the funds available to finance tax cuts or new spending. As we discuss later, these forecasts contain considerable uncertainty. A second problem arises from the treatment of retirement programs. The baseline counts current contributions, but not future liabilities, of the Social Security and Medicare programs. These programs will run substantial cash flow surpluses over the next decade—but substantial deficits over longer horizons. Likewise, trust funds holding pension reserves for federal military and civilian employees are projected to run significant cash-flow surpluses over the next ten years, but their long-term liabilities are not included in the budget.

Accounting for the overall status of such programs within the conventional ten-year budget framework is difficult. But within that ten-year window, it is less misleading to exclude the retirement programs altogether than to include only the contributions. We make such an adjustment in our calculations.

The third problem with the baseline involves CBO projections of discretionary spending. CBO assumes real discretionary spending authority will remain constant over the budget period at the level prevailing at the beginning of the period. Such an assumption implies that real outlays will fall by about 9 percent relative to the population, and by about 20 percent relative to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), over the next decade. Historical experience suggests such changes are unlikely to occur. It would be more reasonable to assume that real discretionary spending will grow with the population, to maintain current services on a per-person basis, or with GDP.

Another set of problems involves the revenue projections. At least three issues arise here. First, several temporary tax provisions are scheduled to expire over the next decade. In the past, however, these “temporary” provisions have typically been extended each time the expiration dates approached, and CBO refers to their prospective extension as “a matter of course.” In light of this practice, current policy is more aptly viewed as including the continuance of these so-called “extenders.” To be clear, we are not arguing that extending the provisions is desirable, just that it is a realistic statement of the current policy trajectory.

A second, and similar, problem with the revenue projections arises because the 2001 tax cut officially sunsets at the end of 2010, meaning the tax code will revert to what it would have been had EGTRRA never existed. Virtually no one believes the tax provisions will actually sunset completely. But exactly which parts of the bill Congress will extend, or when, is unclear. For purposes of constructing a current policy baseline, we assume that current policy toward the sunset provisions is the same as current policy toward the temporary provisions noted above. Thus, we assume that all of the sunset provisions will be removed and the tax cut will be made permanent. As with the temporary provisions, this assumption reflects a best guess about the current policy trajectory, not our view of optimal policy.

Third, the alternative minimum tax (AMT) is a complex levy that is intended to prevent aggressive tax sheltering but instead mainly affects households who have large families or who live in states with high income taxes. Enacted in the late 1960s and strengthened in 1986, the AMT affected about 2 million taxpayers in 2001—or about 2 percent of those with positive tax liability. Because the AMT is not indexed for inflation, the number of AMT taxpayers was projected to rise to 18 million by 2010 under pre-EGTRRA law, and is now projected to rise to 35.5 million by 2010, or about one-third of all taxpayers. No one seriously expects current law to prevail. We define “current policy” towards the AMT as holding constant at 2 percent the share of taxpayers facing the AMT.

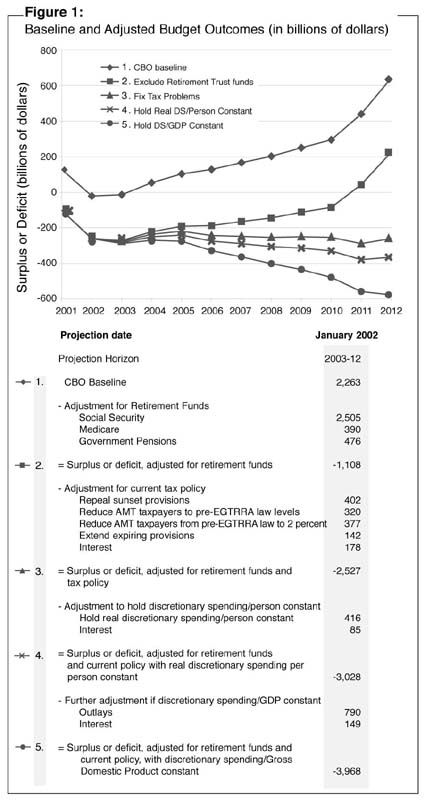

Figure 1 shows the sizable effects of adjusting the surplus for retirement trust funds and current policy assumptions. Removing the accumulations in retirement trust funds changes the January 2002 projection for the budget balance between 2003 and 2012 from a surplus of $2.3 trillion to a deficit of $1.1 trillion. Adjusting the revenue baseline to make EGTRRA permanent, holding the number of AMT taxpayers at 2 percent, and extending the other expiring tax provisions increases the deficit to $3.0 trillion if discretionary spending is held constant on a per-person basis, and to $4.0 trillion if discretionary spending is a constant share of GDP.

Figure 1 also shows the contrast between official and adjusted budget figures on an annual basis. In 2012 alone, the difference is about $1 trillion (if real per-capita discretionary spending is constant) or more (if spending grows with GDP). Perhaps more importantly, the trends are quite different: the CBO baseline suggests that the underlying fiscal status of the government will temporarily improve over the coming decade before deteriorating again as the baby boomers retire, whereas the adjusted baseline suggests no such temporary improvement.

The Long-Term Fiscal Gap

The adjusted budget measures provide a more accurate picture of the government’s underlying financial status than the official figures, but they do not fully reflect the long-term implications of current fiscal choices. To take these factors into account, we estimate the long-term fiscal gap under different policies. The fiscal gap is the size of the permanent increase in taxes or reductions in non-interest expenditures (as a constant share of GDP) that would be required now to keep the long-term ratio of government debt to GDP at its current level at the end of the forecast period. The fiscal gap measures the current budgetary status of the government, taking into account long-term influences.

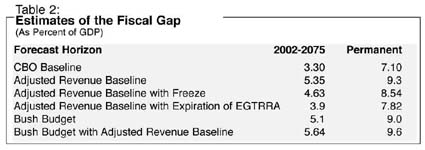

For example, using the CBO baseline noted above, the fiscal gap through 2075 is now 3.3 percent of GDP (table 2). This implies that an immediate increase in taxes or cut in spending of 3.3 percent of GDP—or over $300 billion per year in current terms—would be needed to maintain fiscal balance through 2075. These figures assume that the 2001 tax cut expires in 2010. Using the adjusted revenue baseline, which does not make that assumption, the fiscal gap through 2075 amounts to 5.3 percent of GDP.

On a permanent basis, the fiscal gap is substantially higher—7.1 percent of GDP under the CBO assumptions and 9.3 percent under our adjusted revenue baseline. The permanent effects are much larger because the budget is expected to be running substantial deficits in the years approaching and after 2075. To be sure, no one expects Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, the programs primarily responsible for the fiscal gap, to remain in their current forms over the next seven decades. But the projections indicate what will happen if action is not taken, and the estimates serve as indicators of the changes in spending and revenues that are needed now. Although not shown in the table, the longer such changes are delayed, the more extensive the changes will have to be.

These results, of course, are subject to considerable uncertainty, but the uncertainty does not mean that these projections should be ignored. The serious consequences of a relatively bad long-term outcome should spur a precautionary response from policymakers now. In addition, the longer-term budget problems are driven by demographic pressures that seem relatively likely to occur.

Fiscal Policy Options: The Administration’s Proposals and Alternatives

The Bush administration’s budget for fiscal year 2003 exacerbates an already difficult budget situation. Relative to CBO’s baseline, the administration’s proposals would reduce the unified budget surplus by $1.7 trillion and leave a surplus of about $700 billion from 2003 to 2012 (table 1). The budget would increase the long-term fiscal gap by about 1.8 percent of GDP relative to the CBO baseline, to 5.1 percent of GDP through 2075 and 9 percent on a permanent basis (table 2). If the administration’s budget is adjusted so that the AMT problem is fixed and the expiring tax provisions are extended, the fiscal gap then rises to 5.6 percent of GDP through 2075 and 9.6 percent of GDP on a permanent basis. These figures imply massive fiscal adjustments in the future.

Under the administration’s proposed budget, defense and homeland security spending would rise by about $518 billion over the next ten years. Although the size and composition of the specific defense proposals has raised some questions, higher security spending in general is widely supported in response to the September 11 attacks.

The real question is how such spending will be financed. As a matter of arithmetic, there are only three ways to pay for higher defense spending: reductions in other federal spending, increases in taxes, or increases in borrowing—and borrowing just defers (but does not lessen) the ultimate need to cut other spending or raise taxes. The administration has chosen the first and third methods and raised overall financing needs by proposing tax cuts rather than tax increases.

The administration’s budget proposes significant cuts in discretionary spending outside of defense and homeland security. The proposed cuts for 2003 target community and regional development, low-income energy assistance, environmental protection, job training, and other initiatives, many of which primarily benefit low- and middle-income families.

The administration, furthermore, would increase net borrowing (reduce the surplus or raise the deficit) by $1.7 trillion over the next ten years. Despite the proposed spending cuts, the increase in borrowing exceeds the increases for defense by more than $1 trillion. The main reason why is that the administration actually adds to the financing problem by proposing new tax cuts, including making permanent the components of EGTRRA that are scheduled to expire in 2010. Including the effects of extending EGTRRA, the administration would cut taxes by $746 billion between 2002 and 2012, making the tax cuts themselves larger than the spending increases for defense and homeland security. With the added interest payments due to higher federal debt, the total budgetary costs of the tax cuts would be $932 billion. And, just as the spending cuts appear to hurt low-income households, the proposed tax cuts would predominantly benefit high-income households. The top 1 percent of the income distribution, for example, would receive roughly 36 percent of the benefits from making EGTRRA permanent, but pays only about 26 percent of all federal taxes.

It is worth contemplating the overall message of the combined spending and tax proposals. In the aftermath of last year’s tax cut and the massive deterioration of the government’s financial status, the administration is proposing to finance a war on terrorism by cutting social programs and raising borrowing from young and future generations that are already saddled with substantial fiscal burdens. And the program cuts and borrowing are significantly greater than they would otherwise have to be because of the tax cuts that are also included in the budget.

Alternatives approaches are both available and attractive. One way to improve fiscal balance is to rethink the 2001 tax cut legislation. Allowing the tax cut to expire as scheduled in 2010 would reduce the fiscal gap by about 1.4 percent of GDP through 2075 relative to making the tax cut permanent (table 2). A second option would “freeze” the cut. A freeze would allow the cuts that have already taken effect to remain in place and indeed to become permanent, but would repeal the cuts scheduled to take place in the future. Relative to a permanent extension of EGTRRA, a freeze would reduce the fiscal gap by 0.7 percent of GDP (table 2). These results show that a sizable fiscal gap existed before the tax cut was implemented, that EGTRRA substantially exacerbated the problem, and that freezing the tax cut or letting it expire would be a clear step toward restoring fiscal responsibility.

Interestingly, the estimated shortfall in the Social Security trust fund is 0.7 percent of GDP over the next seventy-five years. Freezing the tax cut, therefore, would save sufficient funds (relative to making it permanent) to eliminate the actuarial imbalance in Social Security through 2075. Allowing the tax cut to expire in 2010 would save twice as much revenue over the same period.

The magnitude of the savings available from curtailing the tax cut relative to the Social Security shortfall may seem surprising. But that is because tax cut figures are often presented over ten years, while the trust fund imbalances are reported over seventy-five years, and because the administration has often argued that the tax cut is moderate while the Social Security shortfall is huge. The truth is that the tax cut has substantial long-term fiscal implications, and is significantly larger than the size of the seventy-five-year Social Security shortfall.

It is also worth noting that an expiration or freeze would impose the costs of the government’s fiscal imbalance on those who are most able to afford it—high-income households. The tax cut in general, and the tax cuts that are scheduled to take place between 2003 and 2010 in particular, are disproportionately weighted toward higher-income households.

The Budget Horizon

Several of the rules governing the current budget process expire this fall, and the administration’s budget puts forward a variety of ideas regarding budget rules and process. Most prominently, the administration’s budget emphasizes a five-year horizon, rather than the now-standard ten-year focus, claiming that 2001 showed ten-year estimates to be too uncertain to be used.

Although ten-year budget forecasts are indeed uncertain, the administration’s shift to five-year figures is problematic for several reasons. First, last year, the administration used the ten-year budget forecast to argue that its tax cut was affordable. Now, by arguing that the ten-year horizon is too uncertain to be useful, the administration undercuts its own arguments for the tax cut. Second, the administration proposes important new provisions that take place beyond the five-year horizon—highlighted by the proposal to eliminate the 2010 EGTRRA sunset—which would be omitted entirely in a five-year budget. Third, it is disingenuous to argue that the decline in the ten-year surplus highlights the inherent uncertainty in medium-term projections when much of the shift reflects the effects of EGTRRA, the administration’s own policy. Finally, the one- and five-year budget surpluses showed larger percentage changes in the past year than the ten-year surplus did, so it is unclear why volatility is a reason to move to shorter budget horizons.

Given all of these reasons, plus politicians who consistently propose tax cuts that do not take place until well into the future, and a long-term budget gap that reveals itself fully only over an extended period of time, it is hard to imagine a more inappropriate budget “reform” than shortening the budget’s time horizon.

Conclusion

The sizable fiscal shortfalls estimated above imply that tax cuts are not simply a matter of returning unneeded or unused funds to taxpayers, but rather a choice to require other, future taxpayers to cover a substantial long-term deficit that last year’s tax cut significantly exacerbated. Likewise, the notion that the surplus is “the taxpayers’ money” and should be returned to them ignores the observation that the fiscal gap is “the taxpayers’ debt” and must be paid by them. Thus, the issue is not whether taxpayers should have their tax payments returned, but rather which taxpayers—current or future—will be required to pay for the liabilities and spending obligations incurred by current and past taxpayers.

Faced with the massive deterioration in the fiscal situation and the need to defend the country after the terrorist attacks, the administration has understandably raised current spending on homeland security and defense. But the administration offers no realistic program for financing this spending increase, and actually worsens the problem through further proposed tax cuts. Freezing the 2001 tax cut at its current levels would be a major step toward fiscal responsibility.

In addition to addressing the fiscal imbalance, Congress and the Bush administration will need to revisit the budget process and rules in the near future. Although the current budget rules have many evident defects, they likely contributed to fiscal discipline during the 1990s. Abandoning them without an adequate replacement would be a mistake, as would reducing the budget horizon to five years.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).