Reforming immigration may be at the top of the news, but as it dominates the headlines our existing system continues apace.

To wit: Today marks the first day U.S. employers can submit H-1B visa applications to the federal government for fiscal year 2014 (for visas beginning on October 1, 2013 through September 30, 2014). Every year at the beginning of April, employers race for a limited number of H-1B visas available—currently set at 85,000, including 20,000 that are set aside for foreign graduates with advanced degrees from American universities. These visas are given on a first-come, first-served basis, resulting in this frenzy.

Last year the race for H-1B visas ended in 10 weeks, whereas the year before, amid a more sluggish economy, it took three times longer. As our report, “The Search for Skills,” highlighted, the demand for H-1B visas over the past decade fluctuated in response to both economic and political conditions. The trend has been one of growth, with the exception of significant declines in demand after the collapse of the dot-com bubble in 2001, September 11, 2011, and the Great Recession that started in 2007.

Since the cap was reached last year on June 11, many of those employers denied an H-1B visa have waited 294 days to file a new application. This long wait period, coupled with better economic conditions, may prompt a quicker end to the race this year. Some predict that the H-1B cap might be reached within five days . But the uncertainty of both the application period and the chance of success make it difficult for employers to predict whether a visa will be available to hire foreign candidates. This makes human resource planning tricky, to say the least.

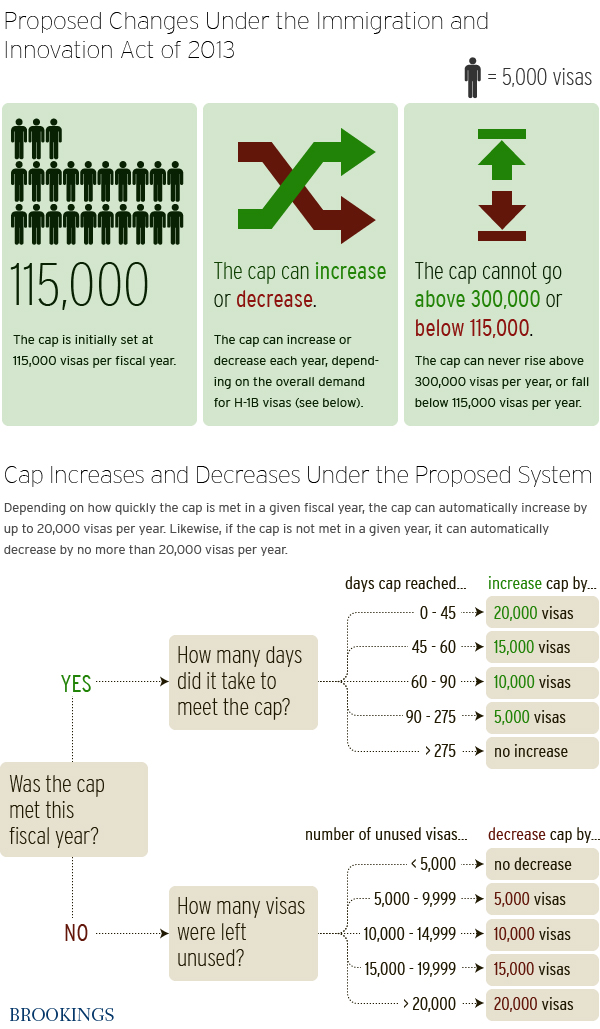

The comprehensive immigration reform debate kicked off with a Senate bill called the Immigration and Innovation Act of 2013 (I-Squared Act). Under this proposal, instead of a static cap, there would be an “H-1B escalator” that automatically adjusts the cap depending on demand. The proposal raises the initial H-1B cap to 115,000 and, depending on how quickly the cap is met in a given year, it would increase incrementally, by up to 20,000 visas the following year. Likewise, if the cap is not met in a given year, it would decrease by no more than 20,000 visas the following year. The I-Squared Act proposes that the cap be no fewer than 115,000 and no greater than 300,000. At the very least, it would take 10 consecutive years of reaching the cap within 45 days to hit the upper limit of 300,000 visas.

The I-Squared Act also proposes to allow foreign students to apply for a permanent green card, to provide unlimited H-1B visas for foreigners with U.S. advanced degrees, to “staple” permanent green cards to graduate degrees in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) earned by foreigners at U.S. universities, and to increase visa fees that would be invested in educating the American workforce in STEM. Some or all of these proposals might be included in the much-anticipated comprehensive immigration reform bill that the Senate “Gang of Eight” is scheduled to introduce sometime this month. A group of House members have also been hammering out a plan that they may make public soon.

The current immigration reform debate is a great opportunity to overhaul the system and move away from an arbitrary race against time for H-1B visas. A new method that structures America’s future immigration system to better meet the demand for high-skilled workers—through less-arbitrary H-1B visa caps, new visa classes, and better-targeted workforce training—will be welcomed by employers and workers alike.

If the H-1B visa system is revamped, this may be the last time we see the race to the H-1B visa cap.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The 2014 H-1B Visa Race Begins Today

April 1, 2013