The Trump administration has radically reshaped U.S. trade policy with extremely high tariff rates. A variety of objectives have been used to justify these tariffs, including reducing trade deficits, retaliation against other countries, national security, and bringing production back to the United States. Unlike these frequently-debated objectives, raising revenue has long been considered an irrelevant factor in modern trade policy—but the Trump tariffs are bringing it back to the forefront.

More than a century ago, tariffs were an important source of U.S. government revenue. Taxing goods at the border, or putting excise taxes on specific goods produced in specific places, is the easiest way to raise funds. Today, it is only younger, less-developed nations who rely on tariff revenue (or sometimes its inverse, export taxes) as a way to fund the government.1 Developed nations use taxes that take serious administrative capacity, like personal and corporate income taxes, sales taxes, value-added taxes, and payroll deductions.

There is a reason that the United States and all other rich nations have moved away from a funding their governments with tariffs: Tariffs are a damaging and inefficient way to raise funds. In short, tariffs are either distortionary taxes that will lead to lower growth (and this will eat into the revenue), or they are distortionary in ways that will allow the circumvention of the tariffs and therefore not raise much revenue (or some combination of both).

In this explainer, I show why tariffs are a particularly bad way to raise funds for the U.S. government.2 The United States raised roughly $30 billion in tariff revenue in August. Trying to make this a permanent revenue stream will be costly. It will hurt consumers. It will hurt the U.S.’ most productive firms. It will reduce economic growth. And, it will undermine U.S. relationships around the world.

Trends in tariff revenue

U.S. tariff increases starting in 2018 moved the U.S. above the OECD average for tariff revenue as a share of GDP. More recent increases are dramatically larger. Based on August 2025 tariff revenue estimates, the U.S. is raising more than 1 percent of GDP in tariff revenue, which is over five times higher than a decade ago and nearly five times the OECD average (figure 1).

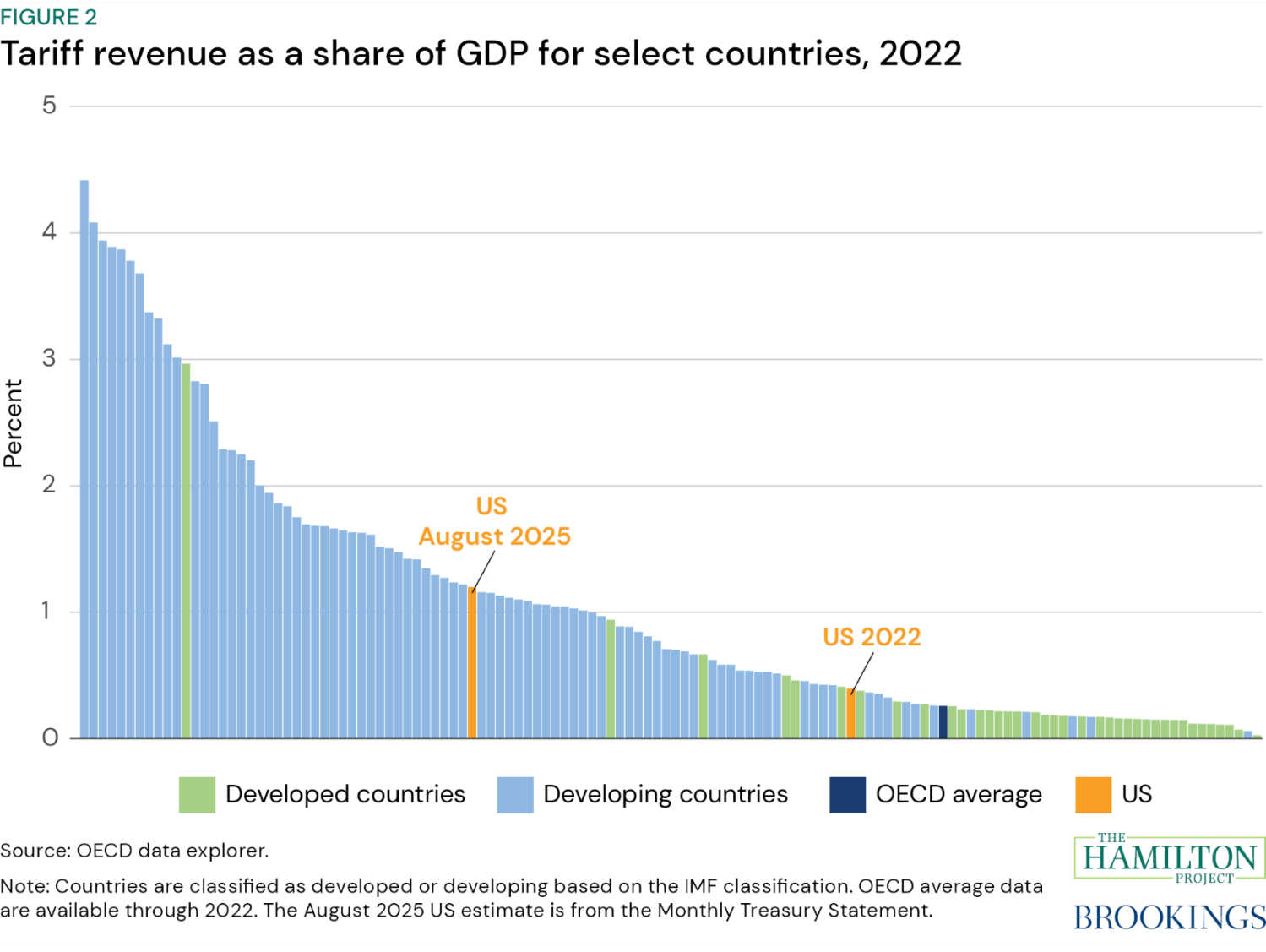

There are countries that raise more than 1 percent of GDP in tariffs, but it is generally small island states or very poor countries that do so. Figure 2 shows tariff revenue as a share of GDP for select countries in 2022 (the most recent data for a wide range of countries) as well as the most recent month of revenue for the United States; appendix figure 1, at the bottom of this analysis, provides additional details. At 1.2 percent of GDP, the U.S. would be joining countries like Zambia and Tunisia, and closing in on Sierra Leonne (though well below the small island states like Vanuata). For a very small country, trade is a much larger share of GDP, hence these countries can raise substantial revenue as a share of GDP from tariffs without prohibitively high tariff rates. For the U.S. to raise revenue on this scale requires very high economically distortive tariffs. The OECD average is around 0.26 percent, and the average of the G7 other than the United States is 0.18 percent.3

Recently, a number of excellent analyses from Yale Budget Lab, McKibbon (2025), and Penn Wharton Budget Model have tried to estimate exactly how much revenue could plausibly be raised. The emphasis of this explainer is not how much can be raised, but why raising sizable revenue through tariffs has large economic costs.

Why do nations trade?

Remembering why nations trade with each other helps to explain why raising revenue via tariffs is so costly. Nations trade because countries are better off specializing in what they are comparatively good at and selling that to other countries while buying from other countries what they specialize in. Think of your family as a country who trades: Few of us still try to build our own houses, grow our own food, act as our own medical professionals, and generate our own heat and energy. We’ve learned we are better off specializing and trading with one another. The same is true of countries.

Countries may specialize in part due to differences in their technology or stock of resources—some countries import oil because they simply do not have any, others export goods that take a great deal of capital to make because they have relatively more capital. Not only do countries specialize, firms do as well. Firms make somewhat differentiated products all over the world. Different medical devices may come from Germany or Iceland, different types of foods from Italy or Morocco, different electronics from Japan or Korea. The gains from trade are not just about efficiency, but consumer choice. Sometimes, American consumers or firms prefer different products or inputs made in different places.

Cutting the United States off from trade with other nations, including doing so to a degree by taxing imports, is inefficient and costly to American well-being. Perhaps more importantly, though, is the damage done to productivity in the economy.

It tends to be the most efficient firms that export. And, it tends to be the most efficient firms that import components into their production process.4 Hence, when trade expands, the more efficient firms grow as they can reach more customers in more markets, and they become a larger share of the economy (and often the most inefficient firms go out of business). These firms also tend to pay higher wages because their workers are more productive. So, as these firms grow, the economy becomes more productive, and this provides an added boost to living standards beyond the standard ideas of gains from trade due to specialization.5

Why is raising revenue via tariffs bad for the US economy?

How does raising revenue via tariffs affect all this? A tariff is a tax; by definition, a tariff is the tax paid by an importer for the right to import a product. When you tax something, you get less of it: This is why nearly all forms of taxation produce some distortion or cause some inefficiency in the economy. An exception is taxing things that the government wants to reduce. Taxes on cigarettes, for example, are intended to reduce smoking by making smoking more costly. In this case, the reduction in economic activity caused by the tax produces the intended benefit through its distortion to the cost of cigarettes.

These cases aside, the goal is generally to raise revenue without causing massive shifts in the economy: The least inefficient tax is one that produces the least amount of distortion. Why do the Trump administration tariffs fail this test?

First, tariffs reduce imports—again, a taxed activity dwindles over time. The U.S. will lose the gains from trade. Consumers will now have to pay extra to access to preferred goods; for example, tariffs hurt U.S. consumers who might prefer Brazilian coffee but see the 50 percent tax on it as too high a cost to pay. Firms will have to pay extra for their preferred sources for inputs and will be unable to continue making or selling goods that they have built businesses around if they suddenly have to pay tariffs. If the tariffs are so onerous that they stop trade altogether, America will have to go back to making some goods it has not made for decades. Doing so would be costly—the fact that they are produced more inexpensively abroad is why Americans import them. It does not make sense to build greenhouses to grow peppers in the winter when you can import them from Chile (who has summer during the U.S. winter).

Second, the current tariffs are inconsistently applied in ways that lead to more inefficiency. The Trump tariffs are set at different levels across both goods and countries. The tariffs include scores of exemptions for particular goods and firms. This could cause the U.S. to import less from higher-taxed sources and more from lower-taxed sources, even if the lower-taxed sources are more costly and less efficient. Even if it costs Korea 20 percent more to make a good than India, if importing from India costs a U.S. firm a 50 percent tariff and importing from Korea a 20 percent tariff, the U.S. firm will switch sources to Korea. In this scenario, the government won’t actually get the 50 percent revenue from imports from India because firms will switch to the lowest tariff option. And U.S. consumers or businesses will have to pay for the more-expensive Korean good. Tariffs generate increasingly less revenue over time as firms and consumers find ways to avoid the tax, not by illegal transshipping, but by changing their supply chains.6

How do tariffs reduce economic growth?

Industries become more productive when they are opened to trade; so, tariffs reduce productivity.7

The economics literature is filled with estimates of what happens when trade opens, as trade policy around the world for the last few decades has tended to open up markets. For example, the International Trade Commission has produced estimates for how a broad shift to opening with many countries would affect that U.S. economy. They found that joining the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) would increase trade by roughly 1 percent, and increase GDP by 0.15–0.2 percentage points. This growth stemmed from relatively small decreases in tariffs, given that the U.S. already had very low tariffs as did many of its trading partners involved in TPP.

What about shutting off trade? An increase in tariffs that stretches across a wide range of sectors is less common. In fact, we have learned about the costs to shutting off trade when it has happened inadvertently. One example (based on the research of James Feyrer) is how some countries saw a sharp drop in trade due to the closing of the Suez Canal between 1967 and 1975. Feyrer demonstrates how closing the canal raised trade costs differently for different countries depending on their location, and this reduced trade. He estimates that a 1 percent change in trade had a 0.25 percent impact on GDP.8

Furceri et al. (2020) look directly at tariffs and their relationship to GDP. They find a 3.6 percentage point increase in tariffs lowers output by 0.4 percentage points. Thus, a 10 percent tariff would generate roughly 1.1 percentage point loss in GDP over time. Furceri et al. also suggest the impact of raising tariff rates may be larger at higher levels of tariffs. How this compares to the estimates from the Suez Canal work depends on how much one assumes tariffs lower trade. Some papers looking at aggregate tariffs find lower numbers (Boer and Rieth [2024] estimate tariffs impact on trade of -0.8), other studies looking at the product level or even country level find much larger impacts on trade.9

Taking a relatively conservative estimate of a one to one reduction in trade, a variety of models have suggested a broad 20 percent tariff could cut trade by nearly 20 percent if other countries retaliated and there were limited exemptions. For the U.S. as of October 30, the official average weighted tariff is roughly that high. But, as of August, the number of exemptions and the fact that some trade (such as U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement compliant trade) has zero tariffs has meant the effective tariff is closer to 10.5 percent. Even at this rate, cutting off 10 percent of trade would suggest an economy 1.5 to 2.5 percent smaller over time, or growth roughly 0.2 percentage points lower every year.

This substantial decrease in economic activity does not just matter for the size of the U.S. economy, it calls into question how much revenue will be raised from tariffs. The White House’s Office of Management and Budget has estimated that 1 percentage point lower growth over 10 years would cost the government roughly $4 trillion. The growth impacts from the current level of tariffs, if they reduced trade by 10 percent, could cost roughly $800 billion.

It is possible trade will not decline at that rate, in particular if there are exemptions and if firms find ways to source from lower tariff destinations. Nevertheless, this scenario would also produce lower tariff revenue (firms are finding ways around the tariffs) and higher distortions (firms are forced to change their behavior to avoid the tariffs), even if the exact rate is somewhat different.

How do tariff supporters argue against these downsides?

The Trump administration has argued that other countries will pay the tariffs. This is incorrect, as it is importing firms or customers who directly pay the tariff. More generously, the argument may be that tariffs will cause foreign firms to cut their prices to avoid losing U.S. customers. This theory does not suggest the foreign firms would offset all the tariffs, and it assumes that the U.S. would gain in some ways while losing from the inefficiency of reducing trade. The problem with applying this theory to the present situation is that there has not been good evidence of foreign firms lowering prices, yet. U.S. import prices have not been falling, and detailed evidence on the trade war in the first Trump term shows exporting firms did not cut their price.

It is possible that some of the terms of trade effect will happen. Typically, the way this occurs is that the tariff-imposing country’s (the U.S.’) exchange rate appreciates, making imports cheaper and partially offsetting the tariff, but at the same time, making exports more expensive and reducing exports. Again, such a process has its costs, as exporters are generally the more productive firms. However, this theory assumes that countries export finished products. When the imported goods are inputs into further production, even if the foreign exporter lowers the price some, the cost of inputs rises and this hurts downstream producers. Ford recently commented it would be doing less investment in the United States due to rising input costs from tariffs.

What are other problems with tariffs?

Raising revenue through tariffs is concerning for additional reasons beyond inefficiency and inefficacy.

Tariffs are a regressive way to raise revenue. If low-income households consume more of their income and spend more on goods (affected by tariffs) than services (less so), tariffs are regressive because they force those with lower incomes to pay out a higher share of their income than higher-income households. While evidence varies as to the exact extent of regressivity, most studies agree that tariffs in the United States weigh more heavily on those with low incomes.10

When tariffs are broadly and haphazardly applied, they lose their strategic value. There may be times when a country needs to use tariffs in a targeted manner to protect a strategic industry or combat unfair trade practices. This application is quite different from broad-based tariffs aimed at raising substantial revenue over time.

Uncertainty around tariff rates and to what countries and what goods they apply makes it harder for firms to plan and invest. Should a firm expand in the United States? Or, will tariffs make it expensive to source key inputs? Given uncertainty, the most conservative position for a firm to take is to hold back on investment while they wait for greater clarity and stability.

The international trade landscape is radically different from what it was over a century ago, when the U.S. last used tariffs to fund the government at scale. Firms use complex supply chains that stretch across borders. Imposing broad-based tariffs will make production in the U.S. more expensive as firms will have to pay tariffs on inputs; taxes on inputs are particularly distortive.

Finally, the fact that these sudden, large, and at times capricious increases in tariffs both breach U.S. international agreements and hit friends and rivals alike has been a serious blow to U.S. diplomatic relations.

I offer two caveats. First, none of this is to suggest that low-tariff or free trade does not have downsides. Rapid increases in trade flows can cause domestic disruptions and winners and losers; in the past, the United States has typically failed to adequately buffer communities and workers hurt by rapid increases in trade flows. But, rapid reductions in trade flows—especially in a world of complicated supply chains—can cause domestic firms to go out of business or cease production. Second, tariffs’ impact on economic growth will appear over a long time horizon, and because the economy is large and complex with many forces operating on it, they may be hard to see, especially if obscured by other large-scale changes like investments in artificial intelligence. But, even if hard to see in near-term data, damage is being done.

Appendix

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The author thanks Aviva Aron-Dine, Lauren Bauer, Chad Bown, and Maury Obstfeld for their feedback. Asha Patt provided excellent research assistance.

-

Footnotes

- See Cage and Gadenne (2018) for a discussion of the use of tariffs as revenue sources across countries over time.

- Clausing and Obstfeld (2025) present a detailed exposition of the economics of the fiscal impacts of tariffs as well as summarize revenue estimates and calculate the revenue maximizing level of tariffs. See also Trade Talks episode 86 for a conversation on the drawbacks of tariffs as a revenue source.

- Data from OECD Revenue Statistics, customs revenue as a share of GDP.

- See Bernard et al (2007) for a summary of the empirical literature.

- Beyond the impacts of trade expanding better firms, there is a literature on how it directly affects innovation. Coelli et al (2022) find a substantial positive impact of trade liberalization on innovation. Bloom et al (2016) show a nontrivial amount of EU innovation from 1996-2007 came as firms innovated in response to Chinese competition. Alternatively, Autor et al (2020) find that firms exposed to large scale import competition may see declining revenues and reduce their R&D expenditures. On net, though, the literature overwhelmingly finds the net effect of trade on innovation is positive.

- The other concern with different rates and exemptions is it encourages firms to spend extensive lobby efforts to get exemptions from tariffs, a costly and wasteful activity.

- See for example Pavcnik (2002) on the impact of liberalization on Chilean firms and Trefler (2004) on the impact of liberalization on Canadian firms.

- It is worth noting that the impact of trade on GDP in Feyrer (2021) is notably lower than other macro estimates like Feyrer (2019) or Frankel and Romer (1999). Feyrer suggests this narrow identification just based on the cost of shipping goods is likely smaller than ones where broader benefits of being connected to other countries may spill into the estimates.

- Estimates of the elasticity of trade to tariffs at the product level are typically notably higher (see Fontagne, Guimbard, and Orefice, 2022). This makes sense given that if just one product from one country is tariffed, it is easy to switch away from that product, shifting trade substantially.

- See Clausing and Obstfeld (2025) or Meng, Russ, and Sing (2023) for a discussion of the literature.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Tariffs are a particularly bad way to raise revenue

November 4, 2025

Key takeaways: