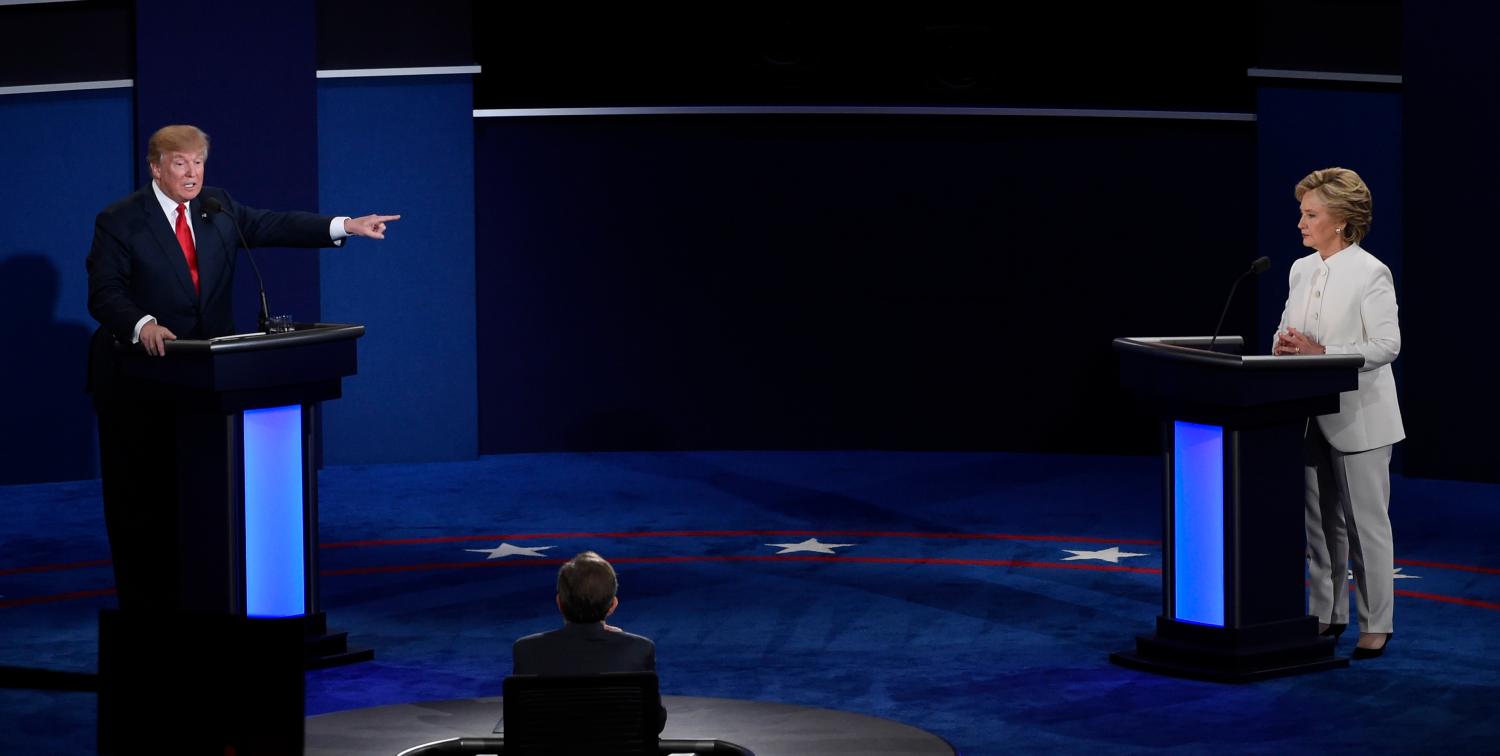

In advance of the Oct. 19 presidential debate at UNLV, The Sunday and the Brookings Institution in partnership with UNLV and Brookings Mountain West are presenting a series of guest columns on state and national election issues. The columns will appear weekly. This column originally appeared in the Las Vegas Sun.

The specter of economic anxiety has loomed large throughout this election cycle. It has been a touchstone for pundits and pollsters when explaining the diehard loyalty of Bernie-or-Bust Sanders supporters or Donald Trump’s path to the nomination, and for the candidates themselves as they make their case to voters that they are the better choice to steer the nation through today’s uncertain economic waters.

A number of indicators — like 75 consecutive months of job growth and a national unemployment rate under 5 percent — tell a brighter story about where the American economy is seven years after the end of the Great Recession. So why the anxiety? It may spring at least in part from other indicators that point to an economic expansion that has left many behind.

As of 2014, 46.7 million people in the United States lived below the federal poverty line (then $24,230 for a family of four) — a number essentially unchanged from poverty’s recession-era peak. Poverty is affecting millions more people — 9 million more than before the recession began and 15 million more compared with 2000 — and its reach has spread rapidly beyond its historic urban and rural homes. The poor population in America’s suburbs climbed by 65 percent between 2000 and 2014, more than twice the pace of growth in core cities. Amid that rapid increase, suburbs became home to the nation’s largest poor population for the first time, outstripping the urban poor population by more than 3 million.

Those numbers upset a long-held narrative about the locus of American prosperity. Contrary to “Leave It to Beaver” stereotypes, it turns out suburbia isn’t immune to poverty (nor was it ever). That might be one reason why a recent Marketplace-Edison Research poll found suburban respondents reporting higher levels of economic anxiety or insecurity than their urban counterparts.

But while economic anxiety writ large may be on the radar this election season, the new geography of poverty is not. Nevadans should care about that oversight because the state has been on the front lines of this historic shift. Between 2000 and 2014, the poor population in the suburbs around Las Vegas and Henderson grew 123 percent — almost double the national increase and the eighth-largest uptick among the nation’s major metro areas.

Fallout from the Great Recession fueled a large portion of that increase, but the rise of suburban poverty is not just a temporary artifact of the downturn. Suburban poverty was on the rise in the Las Vegas region, and across the nation, well before the collapse of the housing market. It has grown amid shifting patterns in immigration and the location of affordable housing, the growing prevalence of low-wage jobs, and the continued suburbanization of population and employment (the population grew by 68 percent in Las Vegas’ suburbs in that 14-year period). And though both people and jobs shifted toward the suburbs in the 2000s, in the process they grew farther apart. The typical resident of suburban Las Vegas saw the number of jobs within commuting distance drop by 10 percent between 2000 and 2012.

The mismatch between where jobs are growing and where low-income workers can afford to live is just one reason being poor in the suburbs poses particular challenges. Many suburbs lack the infrastructure — such as public transit — to connect poor residents to regional economic opportunities. They also tend to have a much patchier safety net, fewer resources and less capacity when it comes to offering the types of work supports and wraparound services that can help poor families find and keep stable employment. Exacerbating these challenges, many existing federal place-based anti-poverty programs — often designed to serve distressed inner-city neighborhoods or struggling rural communities — do not easily map onto the suburban landscape, making it harder for suburbs to overcome deficits in the face of growing need.

That brings us back to the election, and why it matters that this campaign season has failed to acknowledge the new geography of poverty. Delivering on the big-picture economic promises each candidate is making, in a way that stems growing inequality and assuages economic anxiety, will require federal policies that reflect an understanding of the ways in which places and communities shape access to economic opportunity and help determine economic outcomes. There is still time to ask for more specifics on how (or whether) each candidate’s policy agenda is or isn’t taking these issues into account.

For Trump, that will mean bringing his broad-brush economic vision into sharper focus. Trump’s policy platform doesn’t indicate how he would approach poverty alleviation, so the debates offer an important venue for pushing him to engage the issue. And if his push to grow jobs is his anti-poverty plan, he should articulate for voters how his agenda would address the barriers — like lack of affordable housing near job centers or limited transportation options — that can stand in the way of low-income families reaching and maintaining economic stability.

Hillary Clinton has set out a much more detailed agenda around creating “an economy that works for all.” While these issues may not be in the headlines, a voter digging into Clinton’s policy proposals can find a list of actions her administration would take toward “revitalizing the economy of communities that have been left out and left behind.” The language she uses and her proposals, such as creating job opportunities for youth in hard-hit communities and addressing blight in distressed neighborhoods, articulate the importance of place in delivering economic opportunity.

But the only mention of the suburbs to be found in that agenda is in the pitch that these policies are needed, at least in part, because “our cities should do as well as our suburbs.” For Nevada, where 42 percent of the state’s poor population lives in the suburbs of Las Vegas, and where more than half of the suburban poor population lives in high-poverty neighborhoods (on par with urban poor in the region), voters should be looking for Clinton to clarify that her policy playbook will be more responsive to the shifting geography of poverty than this rhetorical shorthand suggests.

The Census Bureau will release new poverty numbers this week, and even if the news is better than it has been in the past seven years, there remains a great deal of ground to make up and a new landscape in which to do it. In the home stretch of this election season, there’s still time to make poverty and its new geography an explicit part of the conversation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Suburban poverty is missing from the conversation about America’s future

September 15, 2016