Markets are focused on the European growth model, which is suffering after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The damage caused by the loss of access to cheap Russian energy is material, but there is a deeper, structural reason why Europe lags the U.S. in the post-COVID recovery. Lack of fiscal union and debt overhangs mean countercyclical stimulus is insufficient after every adverse shock, which is why Europe also lagged the U.S. recovery after the global financial crisis. Fiscal union will require hard compromises on debt and transfers, without which the risk is high that the eurozone heads for Japanification, where high debt is sustainable—amid low growth—only due to central bank yield caps.

Structural drivers of European weakness

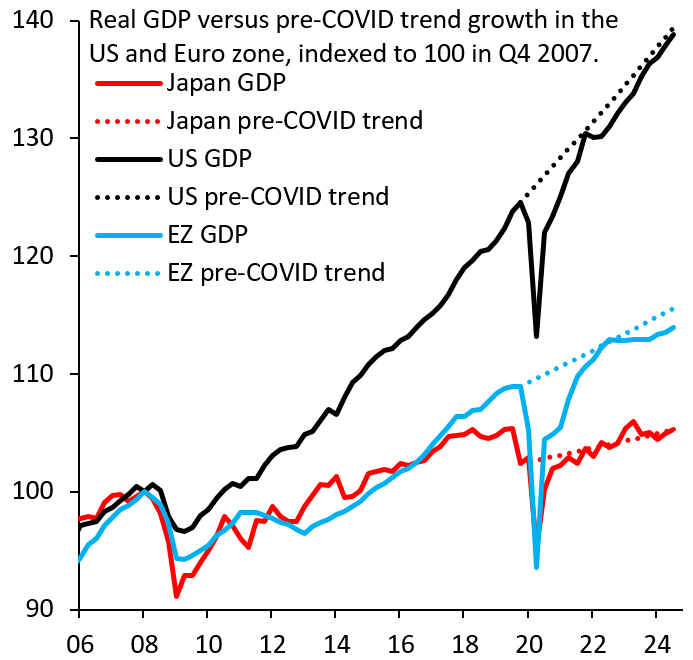

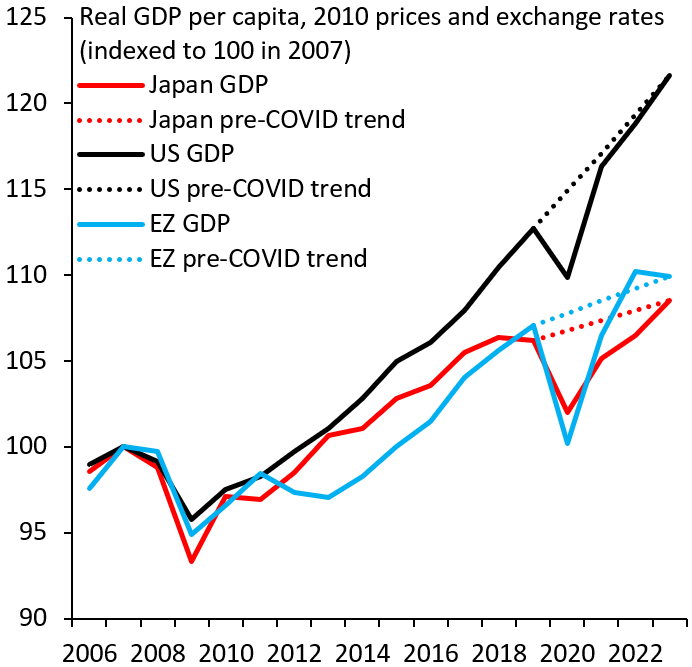

Eurozone underperformance vis-à-vis the U.S. is nothing new. The global financial crisis in 2008 set the stage for a decade of underperformance, with GDP in absolute (Figure 1) and per capita terms (Figure 2) falling increasingly behind the U.S. The distinction between headline and per capita growth is important, because U.S. outperformance often gets linked to faster immigration. That is clearly not the principal driver, as U.S. outperformance remains substantial even in per capita terms.

Figure 1. Real GDP vs. pre-COVID trend growth in the US and eurozone, indexed to 100 in A4 2007

Figure 2. Real GDP per capita, 2010 prices and exchange rates, indexed to 100 in 2007

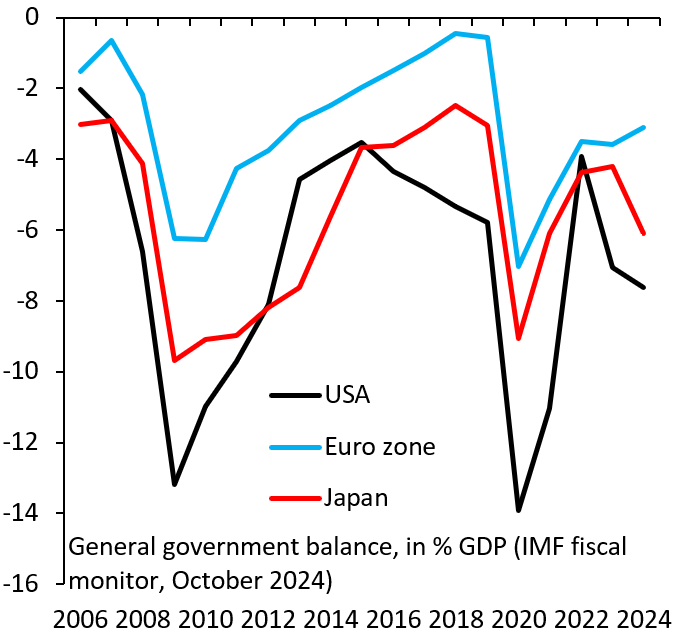

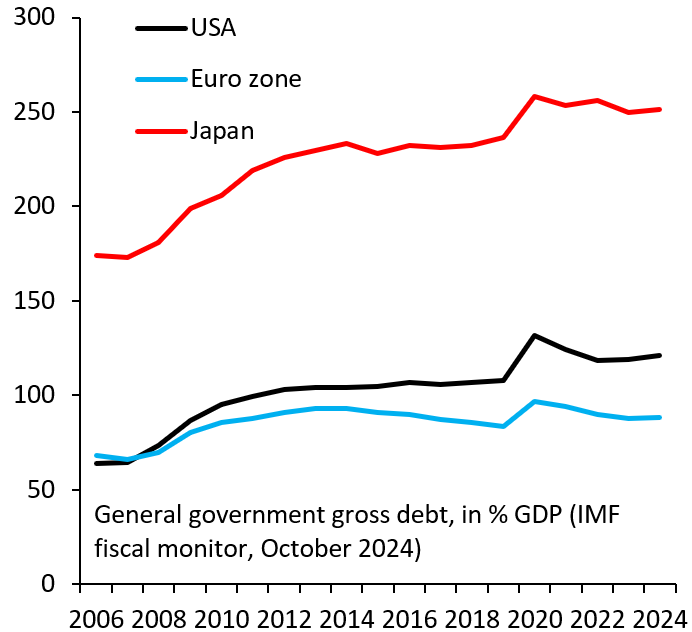

Instead, the lack of fiscal union is the true—and structural—reason for eurozone underperformance. Together with debt overhangs in Italy, Spain, and increasingly France, this means there is insufficient stimulus after every shock because the currency union descends into wrangling over how to pay for stimulus when bad shocks hit. Figure 3 shows how this played out during the 2008 crisis and the COVID-19 shock. In both cases, the eurozone general government deficit widens less than elsewhere (Figure 3), while indebtedness also rises by less (Figure 4). Of course, joint EU debt issuance during the COVID-19 pandemic marks a big step forward, but that joint issuance was a one-off and is highly contentious. As a result, because countercyclical stimulus will remain too small, permanent scarring and hysteresis will keep arising from what should be cyclical disruptions.

Figure 3. General government balance, in % GDP

Figure 4. General government gross debt, in % GDP

Hard compromises are needed in the eurozone North and South to make fiscal union happen. An equitable fiscal union means countries should enter with similar levels of government debt. That condition is clearly not met in the eurozone, where debt stands at 40% and 60%, respectively, in the Netherlands and Germany, while it lies at 110%, 140%, and 100% in France, Italy, and Spain, respectively. As our most recent blog post noted, there is ample private wealth in high-debt countries that could be taxed to reduce public debt levels. Such a tax could be made progressive, i.e., could be linked to household incomes, and would signal to financial markets that debt reduction is now a policy priority, which in and of itself would help preserve market access in bad shocks without having to rely on emergency bond purchases by the European Central Bank (ECB).

Political resistance to wealth taxes is high, of course. This resistance reflects popular perception that the probability of crisis is low, which is true as long as the ECB stands ready to cap yields whenever bad shocks hit. The ECB acted this way mid-2022, when rising inflation drove global yields up, and has since introduced its new transmission protection instrument (TPI). The TPI allows the ECB to cap yields with no ex post conditionality, unlike Draghi-era outright monetary transactions (OMT) with IMF-style conditionality, which TPI has de facto replaced. Prospects for fiscal union are therefore—unfortunately—inversely linked to the role the ECB plays in sovereign debt markets: The ECB keeps debt crises at bay, at the cost of making needed reforms less likely.

Heading for Japanification

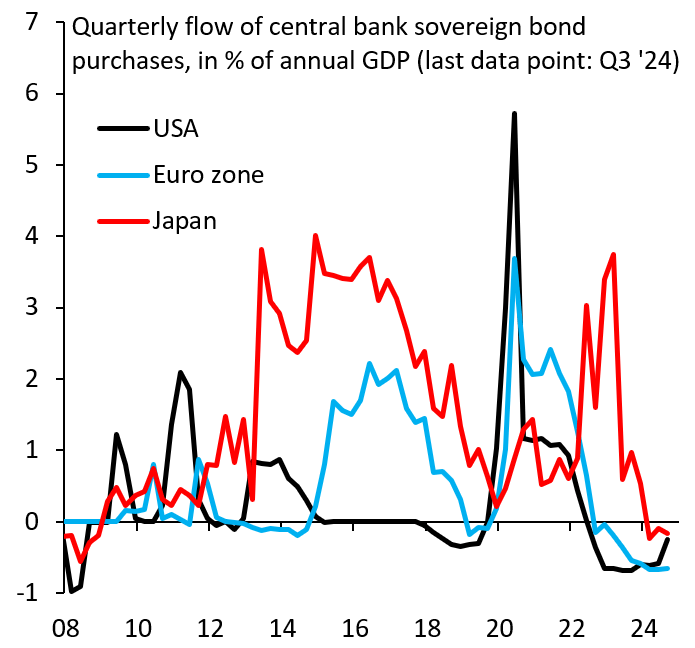

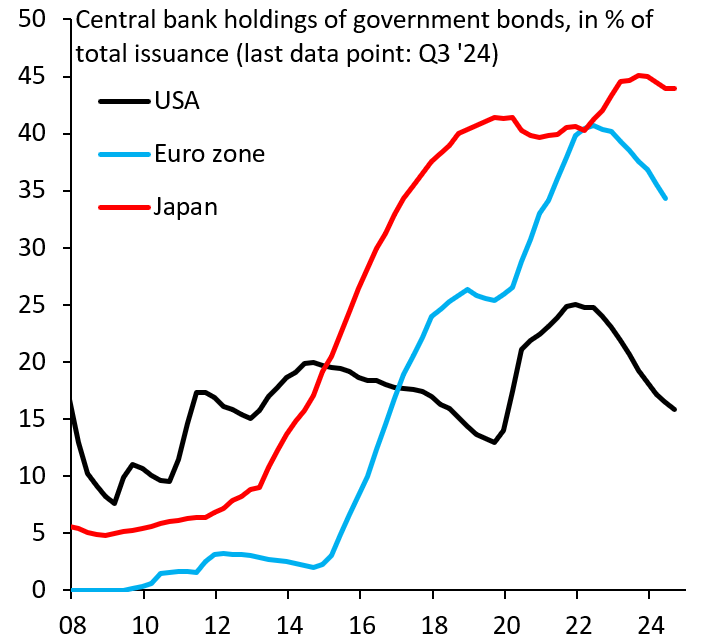

Without a grand bargain on debt and fiscal union, the eurozone is at serious risk of Japanification. This is an equilibrium of low growth and high debt, where only central bank yield caps ensure debt is sustainable. Already, the profile of ECB sovereign bond buying resembles that of the Bank of Japan much more than that of the Fed (Figure 5), with cumulative purchases—measured as the share of outstanding government debt—exhibiting the same upward step function as in Japan (Figure 6), in contrast to the Fed, where sovereign bond holdings have a more cyclical and stable pattern. The growing role of the ECB in debt markets risks locking the eurozone into the low-growth equilibrium that has prevailed in Japan for a long time.

Figure 5. Quarterly flow of central bank sovereign bond purchases, in % of annual GDP

Figure 6. Central bank holdings of government bonds, in % of total issuance

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Structural drivers of eurozone underperformance

December 20, 2024