The rise of fragile families—families that begin when a child is born outside of marriage—is one of the nation’s most vexing social problems. In the first place, these families suffer high poverty rates and poor child outcomes. Even more problematic, the very groups of Americans who traditionally experience poverty, impaired child development, and poor school achievement have the highest rates of nonmarital parenthood—thus intensifying the disadvantages faced by these families and extending them into the next generation.

Nonmarital births have increased precipitously in the past forty years, especially among minorities and the poor, the groups of greatest concern. Today more than 70 percent of black children, 50 percent of Hispanic children, nearly 30 percent of white children, and 40 percent of all children are born outside marriage, assuring the persistence of poverty, wasting human potential, and raising government spending. Reducing nonmarital births and mitigating their consequences should be a top priority of the nation’s social policy.

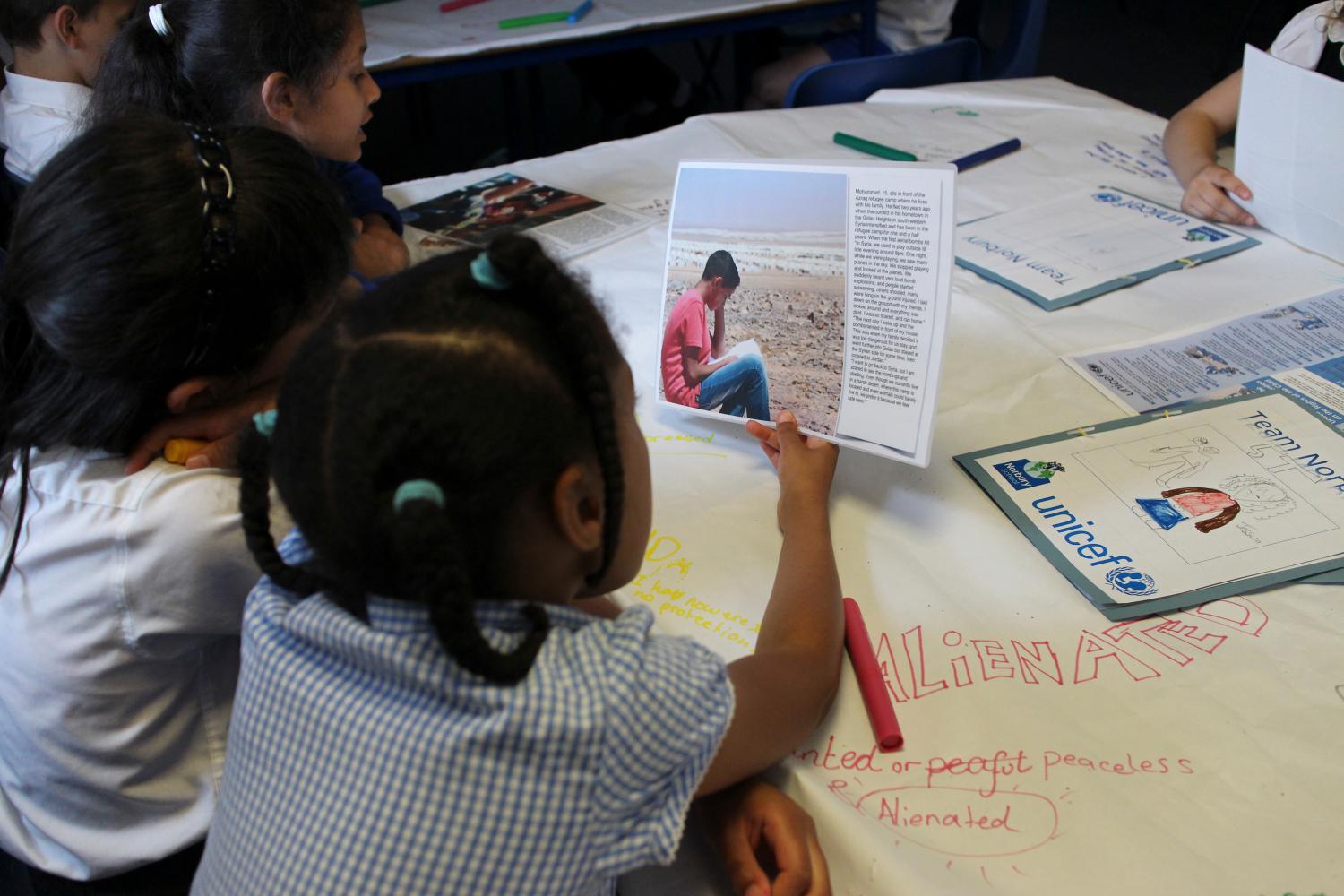

Social science aims to illuminate the choices available to policy makers both by promoting better understanding of social problems and by providing reliable information about the effects of potential solutions. And yet, until a decade ago, social scientists had accumulated little data about nonmarital childbearing and its consequences for parents, children, and communities. Recognizing the need for such data, in the late 1990s researchers at Princeton and Columbia universities organized the first large-scale study of nonmarital childbearing and its consequences. The researchers randomly sampled parents of approximately 5,000 newborns (including 3,600 nonmarital births) in twenty of the nation’s largest cities. For the past decade, the research team has been following the parents and children to learn more about their capabilities and experiences. The findings of this research, known as the Fragile Families Study, have been reported in numerous academic articles, newsletters, and books. Now the most important findings have been pulled together in the new volume of the journal The Future of Children. Here we provide a brief overview of those findings and draw from them what we believe to be the most important policy recommendations.

The Fragile Families Study Findings

Four findings in particular stand out. The first, a big surprise when it was first published, is that a large majority of unwed parents have close and loving relationships at the time of their child’s birth. A little more than half the unmarried couples were living together when their child was born, and an additional 32 percent were in dating relationships. One-night stands these were not. The couples talked readily about marriage, with 87 percent of the fathers and 72 percent of the mothers giving their relationship at least a 50/50 chance of leading to marriage.

The second, more sobering, finding is that unwed parents have a host of demographic and human capital characteristics that complicate getting good jobs, forming stable families, and performing successfully as parents. Unwed parents in the sample were much younger than the married parents—the mothers almost six years younger, and the fathers, four. Only about 4 percent of the married mothers, but 26 percent of the unwed mothers, were teenagers. And even though the unwed parents were younger than their married counterparts, about three times as many had a previous birth with another partner, leaving many of the children in these households to deal with a parent figure (the mother’s new boyfriend or husband) inside their home and a biological parent outside the home, an arrangement that can be stressful for all involved.

The human capital and health differences between the two groups are equally striking. Unwed mothers were more than twice as likely to lack even a high school degree, while married mothers were nearly fifteen times more likely to have graduated from college. In part as a result of their educational advantages, married mothers on average earned more than twice as much as unwed mothers, about $25,600 compared with $11,100. The lower earnings of unwed mothers contributed to a poverty rate that was more than three times as high (43 percent) as that of married mothers (14 percent). The differences between unwed and married fathers were similar. Unwed parents also differed in health status and behaviors detrimental to health. They were more likely to report being in poor or fair health, more likely to have a health-related limitation, and much more likely to use illegal drugs. Nearly 8 percent of unwed mothers reported heavy drinking, about four times the rate among married mothers.

A final difference in human capital between the two groups is of special concern. More than 36 percent of the unmarried fathers had a prison record, five times the share of married fathers who ever spent time in prison. Research shows that incarceration disrupts fathers’ relationships with their families, requires a difficult (and thus often unsuccessful) transition back to life in the community, and greatly reduces the chance of finding employment. Even when these fathers do find employment, they work less and have lower wages. As if these disadvantages were not enough, research consistently shows that recidivism rates are high, deepening even further the disadvantages associated with having spent time in prison.

The third set of findings is equally sobering. Relatively few of the unwed couples were able to form stable relationships. At five years after the birth of their child, only about 35 percent were still together. Breakups were less likely among couples in which fathers had higher earnings, mothers had more education, attitudes about marriage were positive, and relationship quality was good.

Relationship dissolution is only the first step toward household instability. Once the couple splits, both of the unwed parents usually go on to form new relationships and often to have additional children by other partners. Over the five years of the study, over a quarter of unwed mothers lived with a new partner, and a fifth had a child with a new partner. Changes in dating partnerships were even more common. Nearly 60 percent of mothers who were single at birth experienced three or more relationship transitions over the five years.

The parental split reduces substantially the contact between the children and their fathers. By year five, only 51 percent of the fathers involved in splits saw their child even once a month. In effect, when couples break up, within five years half the children are destined to have little contact with their father. It would seem very difficult for a father who sees his child once a month or less to provide effective parenting.

Finally, and most important, these differences in demography, human capital, health, and household stability are associated with negative developmental outcomes for children born to unwed parents. Relationship instability in particular is linked with both poor test performance and behavioral problems in children, especially boys. With unstable and increasingly complex home environments, and with children’s development already moving off track by age five, it is difficult to be optimistic that most of the children of unwed parents will grow into flourishing adults.

Policies to Address the Fragile Families Findings

The Fragile Families Study has clearly fulfilled its goal of providing abundant information about couples whose children are born outside marriage and about those children. With 40 percent of the nation’s children—including a disproportionate number of poor and minority youngsters—now being born to unwed parents, the Fragile Families Study should raise grave concerns among policy makers about the problems faced by these families and their children. Although the Fragile Families Study was not designed to test the effectiveness of programs to help these families, we think, based on the Fragile Families Study and other studies, that four policy initiatives are justified.

Because few social interventions produce major or immediate improvements in the problems they address, there can be little doubt that nonmarital births and their attendant problems will still be with us for several generations. Thus the nation needs to maintain and even strengthen its safety net for single parents. We doubt that the safety net will ever provide these parents and children with enough cash and in-kind benefits to maintain a decent lifestyle, so the nation should, for both custodial and noncustodial single parents, strengthen its welfare policy emphasis on work and public work supports such as cash earnings supplements and child care. The federal government and the states should also work with noncustodial parents to create child support payment levels that they could be reasonably expected to meet. We are especially concerned about the weakness in the cash benefits part of the safety net revealed by the current recession. States must find ways to balance strong work and child support requirements with cash benefits and adjustments in child support for those who cannot find work.

The second policy initiative is preventing nonmarital pregnancies. Policy simulations in the new Future of Children volume show that mass media campaigns that encourage men to use condoms, teen pregnancy prevention programs that discourage sexual activity and educate teens about contraception use, and Medicaid programs that subsidize contraception all reduce pregnancy rates among unmarried couples—in the process saving more than enough public dollars to cover their costs. Happily, the federal government is now at various stages of implementing policies that are responsive to two of the three findings from the policy simulations. The Obama administration’s plan to expand teen pregnancy programs, now funded by Congress and being aggressively implemented, holds great promise for further reductions in teen pregnancy rates. In addition, a provision in the new health care legislation gives states the option to cover additional women with family planning services without the need for a waiver as required under current law. This reform is consistent with the simulation’s finding that additional Medicaid family planning coverage for women would be cost beneficial. With two of the three reforms recommended by the simulations already being implemented, only the third recommendation—media campaigns encouraging men to use condoms—has not already been addressed by policy makers. Given the evidence from the simulation of this policy, we think spending about $100 million a year on a social marketing campaign would be good policy and would pay for itself.

A third area needing policy reform is the U.S. prison system. The Fragile Families Study found that unwed fathers are more than five times as likely to serve prison sentences as married fathers are, with profoundly negative effects on their life after prison. So serious are the consequences for employment, integration into community life, and subsequent imprisonment that a prison sentence has come to be the modern equivalent of the scarlet “A.” And yet good studies find that many long prison sentences in the United States—which has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world—are the result of victimless drug crimes and recommitment for minor parole offenses.

Rethinking sentencing policy is especially urgent because research shows how difficult it is to rehabilitate men once they have served prison terms. A key goal should be to revise mandatory sentencing laws in accord with the recommendations of the United States Sentencing Commission—in this case, to shorten the sentences of nonviolent minor drug dealers, or even to address their offenses outside of prison. The fall 2008 issue of The Future of Children, edited by Lawrence Steinberg, reviewed impressive evidence that community programs that worked with adolescents and their parents were not only more effective than imprisonment in preventing subsequent crimes, but also were more cost-effective. Policy makers should make every effort to modify federal and state mandatory sentencing laws to keep young offenders out of prison.

Regardless of the timing, the Obama administration has joined the issue on what is arguably the most important provision in federal law on marriage and fatherhood. The marriage grant program provides an average of $610,000 for five years to 125 community-based marriage projects. Grantees include churches, postsecondary schools, county and state governments, nonprofit and for-profit entities, and faith-based organizations. Most of the programs provide marriage education for low-income couples, but some conduct marriage education for high school students, others provide divorce reduction programs, and still others combine educational activities with public advertising campaigns on the value of healthy marriage and the availability of services. Similarly, the fatherhood grant program funds 100 projects that promote responsible fatherhood by helping community-based organizations and others run programs that provide healthy marriage, responsible parenting, and economic stability services, including employment or skills training assistance, as well as encouraging fathers to make their child support payments.

The Obama administration would replace these networks of marriage and fatherhood programs with a “Fatherhood, Marriage, and Families Innovation Fund.” Rather than making grants to community-based organizations, the federal government would allocate funds to states or coalitions of states for two types of programs: “comprehensive responsible fatherhood initiatives” and “comprehensive family self-sufficiency demonstrations [that] address the employment and self-sufficiency needs of parents.” The Obama proposal would end funding for the current marriage and fatherhood programs and set in motion the new state-run programs. Thus, it appears that the emphasis on couple relationships and marriage in the Bush programs would give way to an emphasis on fatherhood and self-sufficiency, although marriage programs would be allowed. The Obama initiative also would focus much more on assessing program effectiveness than the Bush marriage and fatherhood grants, which have received virtually no evaluation.

Since the Obama administration announced its innovation fund proposal last winter, a program designed by the Bush administration as part of its marriage initiative has begun publishing results that bear directly on marriage and fatherhood programs. A random-assignment evaluation of Bush’s Building Strong Families (BSF) demonstrations in eight sites was mounted to test the effects of marriage education and services on young unwed parents. More than 5,000 couples participated either in a control group that received no services or in a treatment group that received three types of services: marriage education group sessions; support from a family coordinator who encouraged participation in the group sessions and provided ongoing emotional support to the couples; and referral for services such as job search, mental health, and child care. The marriage education sessions were guided by curriculums designed specifically for low-income couples to teach skills including effective communication, showing affection, managing conflict, co-parenting, and family finances. The curriculums offered between thirty and forty-two hours of group sessions.

Interim results fifteen months after couples had applied for the program can be summarized in four points. First, averaged across all eight sites, there were no differences between control and program couples on any of the major outcomes. Second, the programs nonetheless had positive effects on black couples, who improved their ability to manage conflicts and avoid destructive behaviors, reduced infidelity and family violence, and increased effective co-parenting. Third, the Oklahoma City site produced a host of positive impacts, including keeping couples together, increasing their happiness, and helping them express support and affection and use constructive rather than destructive behaviors during conflict, among others. The positive results for black couples appear to be driven primarily by the Oklahoma program. Fourth, couples in the Baltimore program experienced some negative impacts, including fewer couples maintaining their romantic involvement, lower expression of support and affection, more severe violence against women, lower quality of co-parenting, and less father involvement.

It is disappointing that the BSF program had no effects overall, and the Baltimore results are disturbing. We urge further study of the Baltimore site, but note that the couples there were the most disadvantaged of all participants, and their relationships were more tenuous, which suggests that there could be thresholds below which participation in marriage education programs is not advisable. But despite these disappointments, the finding of benefits for black couples and the positive effects found in Oklahoma imply that a program serving black couples—who have the highest rates of unwed parenting—built on the Oklahoma model could produce similar positive effects. Moreover, initial evaluations of many social programs produce findings not unlike those reported in the BSF evaluation; indeed, findings are often even more discouraging. From this perspective, the early findings showing a range of benefits for the biggest subgroup (blacks) and for the biggest individual program (Oklahoma) seem relatively encouraging. It would be premature to use the BSF results to conclude that marriage education programs for unwed couples don’t work, or to abandon research and demonstration programs that attempt to promote healthy relationships between couples in fragile families.

A compromise along these lines with the Obama proposal lies readily at hand. The criticism that the Bush network of 125 marriage projects has provided virtually no evaluation evidence is entirely correct. As a result, no one has any idea whether these programs are working. We recommend that the Obama administration open a new round of marriage-promotion grants, allowing the 125 existing programs to apply if they so choose, but basing decisions about funding in the new round on the quality of the new proposals and on the reliability of the evaluation plan that would be required for every proposal. Projects should also be required to report a standard set of results that include the types of measures reported in the BSF evaluation.

The administration is proposing to spend $500 million over three years on its initiative. We would recommend spending about $50 million of the $500 million specifically on marriage education projects that attempt to replicate and expand the approach taken in the Oklahoma program. This would leave $450 million of the $500 million for the fatherhood and self-sufficiency programs favored by the administration. Projects that bring fatherhood programs and marriage programs into a close working relationship to promote child well-being would be especially welcome. The key point is to follow up on what has been learned from the BSF evaluation and evaluations of fatherhood programs in recent years.

Although the administration should consult widely to learn more about the program characteristics that may have played a role in producing the negative impacts in Baltimore and the positive impacts in Oklahoma and among black couples, we think two unique characteristics of the Oklahoma program are especially important. The two characteristics are involving married couples as well as fragile families in the marriage education groups and focusing strongly on attendance. Average attendance in the Oklahoma program was far superior to that in the other programs. About 55 percent of participants in Oklahoma received at least 60 percent of the marriage curriculum. In Indiana, where attendance was next best, 33 percent of participants reached that rather low bar. In the remaining six programs, an abysmal average of 14 percent did so. Half the participants in four of the eight programs failed to attend even a single session. A fair test of the marriage curricula requires that ways be found to boost attendance—as was in fact achieved by the Oklahoma program.

The most important conclusion from the Fragile Families Study is that these families play a central role in boosting the nation’s poverty rate and that they and their children contribute disproportionately to many other serious social problems. Our policy recommendations would in all likelihood have only modest effects on poverty and other social problems, but until more disadvantaged children live in stable households with both of their biological parents sharing healthy relationships, the negative effects of unwed births will continue to trouble the nation. Meanwhile, policy makers should strengthen the safety net that provides cash and in-kind support to custodial and noncustodial parents and helps them find work; continue to aggressively implement and even expand the prevention policies that have been shown to reduce nonmarital births and save money; revise criminal sentencing laws and experiment with policies designed to help men avoid prison and integrate back into their communities when prison cannot be avoided; and refuse to give up on healthy marriage programs that have shown at least some promise in achieving the stability and positive parent relationships that could prove helpful for these couples, their children, and the nation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).