I. Introduction

Ukraine faces escalating pressure from the United States to make peace with the Russian Federation. Ongoing peace negotiations would require Ukraine to make many painful concessions, including ceding some of its territory and agreeing not to join NATO. Following talks between U.S. and Ukrainian leaders, Ukraine has looked to Europe for support and security guarantees. Even as diplomatic efforts are ongoing, the war continues, with Russian drone strikes regularly pummeling Ukrainian population centers.

Tipping the balance requires heightened pressure on the Russian economy and its sources of tax revenues. Carefully coordinated, specifically targeted, and legally unassailable sanctions from the United Kingdom and Europe would give Ukraine greater leverage at the negotiating table, increasing the chances of a just and lasting peace. European policymakers who want to help Ukraine and protect their own nations must act decisively to enforce such sanctions against Russia’s “shadow fleet” of oil tankers. As we argue below, this can most efficiently be accomplished by encouraging flagging states to require adequate insurance for vessels that fly their flags.

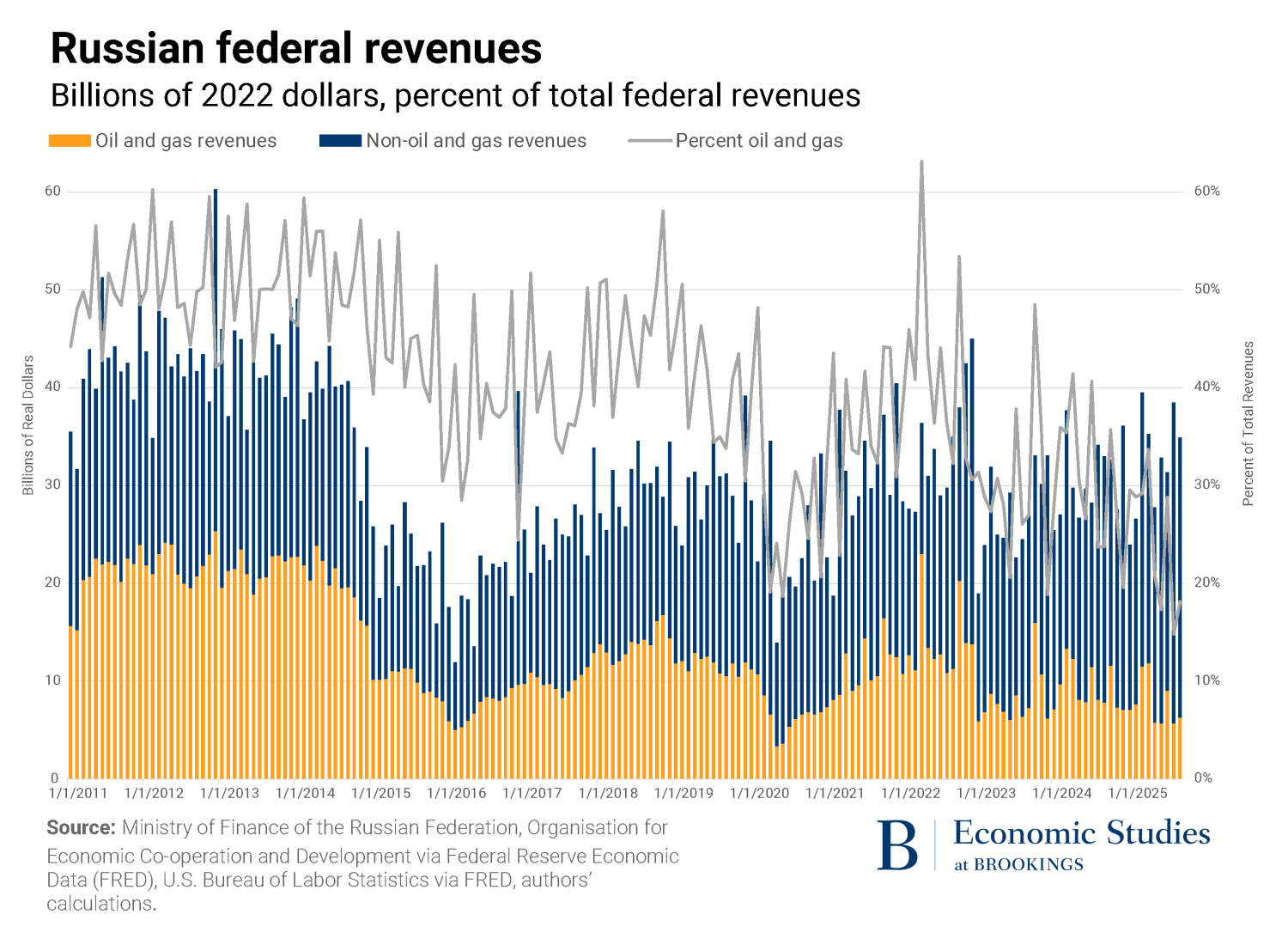

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the United States, United Kingdom, European Union, and their allies levied a barrage of sanctions on the Russian Federation. Russia’s energy industry has been the main target of these sanctions, and for good reason. Exports of fossil fuels, particularly crude oil, drive Russia’s economy. In 2021, crude oil exports accounted for 6% of Russian GDP, while total fossil fuel exports comprised 14% of GDP.1 Fossil fuel exports are also an important source of government funding for Russia. In the decade before the invasion of Ukraine, taxation of the oil and gas sector made up 44% of federal budget revenues. Although Russia’s economy has diversified away from oil and gas somewhat since the invasion of Ukraine (due to sanctions as well as increased military spending), fossil fuel taxes still accounted for around 24.5% of budget revenues over the first three quarters of 2025.

Before the invasion of Ukraine, around 40% of the gas and over one-quarter of the oil imported to the EU came from Russia. This trade accounted for more than half of Russian fossil fuel export revenues in January 2022. The EU has since taken steps to break this dependence; its fifth sanctions package banned the import of coal and other solid fuels from Russia, and the sixth package banned seaborne crude oil and refined petroleum products. As a result of these efforts, EU imports of Russian fossil fuels fell by nearly 90% between 2021 and 2024.2 For their part, the U.K. and U.S. already did not depend on Russia for oil, since both nations produce most of the crude oil they consume domestically.

Although the EU, U.K., and U.S. now consume very little Russian oil directly, they are still vulnerable to changes in Russian production and export levels due to Russia’s prominence in the global oil market. Russia accounted for around 10% of global oil exports in 2024; completely shutting off this production would lead global oil prices to spike—with an increase of approximately 67% if historical price elasticities are in force.3

Concerns of an energy crisis have guided western sanctions actions since 2022. Shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine there was widespread concern that an aggressive sanctions regime might cut off Russian exports altogether, thereby initiating a global economic downturn. These fears are now largely assuaged, as total Russian crude oil export volumes have remained highly consistent, averaging between four and five million barrels per day over the last several years. Nevertheless, keeping Russian crude oil flowing was a key priority of the sanctioning coalition, even as they sought to limit Russia’s ability to fund its war. The price cap on Russian oil and refined petroleum products implemented by the EU, the G7, and Australia (the “price cap coalition”) was designed to compromise between these two goals.

The overall price cap on seaborne Russian oil consisted of three separate price caps. The first cap, effective in early December 2022, set the price of seaborne Russian Urals crude oil at $60 per barrel. It was followed by a $100 per barrel cap on high-value refined petroleum products and a $45 per barrel cap on low-value refined petroleum products, both taking effect in February 2023. These values were chosen to reduce Russia’s oil revenues while remaining above the marginal cost of production, thereby preserving Russia’s incentive to export. The caps applied to all transactions that used services provided by companies based in coalition countries, including financing, customs brokering, and the provision of insurance. Coalition companies held a near-monopoly on many of the services required for shipping, particularly in the insurance industry. The International Group (IG) of Protection and Indemnity (P&I) Clubs insured 90% of all vessels by capacity and consisted exclusively of American, European, and Japanese insurance providers. Coalition countries also agreed to prohibit the importation of almost all Russian oil and oil products.

Among the most important services covered by the price cap is “flagging.” Merchant vessels must be officially registered with a “flag state” under whose laws they agree to operate. Conversely, a flag state is responsible for conducting oversight and enforcing regulations on vessels flying its flag. As a result, shipping companies often choose to register their vessels with flag states that are different from the vessel’s true country of ownership in order to avoid stricter oversight or higher tax rates. Such flags are referred to as “flags of convenience.” By carrying capacity, 70% of maritime transport vessels fly flags different from their country of ownership. Globally, the most common flags are those of Greece, China, and Japan, which collectively represent more than 40% of global shipping capacity.

As a means of enforcing the price cap, members of the price cap coalition began sanctioning, or “designating,” individual vessels that sold crude at above-cap prices. These sanctions raised barriers to trade for noncompliant ships and their owners, barring them from ports and access to financial services. The American dollar’s position as the primary currency of the global oil trade (the “petrodollar”) makes U.S. blocking orders particularly powerful because a blocked exporter loses the ability to transact in dollars, seriously disrupting its operations. From February 2022 through January 2025, the U.S. sanctioned 216 Russian-controlled vessels, far more than the EU and the U.K. over that period. This dynamic has since reversed. The EU and U.K. sanctioned hundreds of additional vessels in 2025, while the U.S. has not designated a single additional tanker during the second Trump administration. At the time of writing, the EU has sanctioned around 600 vessels, and the U.K. has sanctioned nearly 500 vessels.

The U.S. is also falling behind other nations in updating the price cap to accommodate the evolving global oil market. As originally designed, the price cap ceases to be “binding” whenever the market price of Urals crude is below $60 per barrel, meaning vessels using coalition services could once again transport Russian oil. Such a decline occurred in mid-2025, leading to a rise in the percentage of Russian oil exports carried by coalition owned or insured tankers. In response, the rest of the price cap coalition, including the EU, the U.K., Canada, Australia, and Japan, lowered the price cap on crude oil to $47.60 per barrel effective September 2025. Furthermore, the EU (but not other coalition members) introduced a mechanism to automatically adjust its price cap every six months, setting a new cap at 85% of the average price of Urals over the preceding six-month period. Despite these innovations, the EU and other coalition members have not changed their high- and low-value refined product caps. The U.S. is the only coalition member to leave the crude cap at its original level.

Coalition sanctions, including the price cap, were initially successful at driving down Russian fossil fuel revenues, particularly in the months immediately following the implementation of the price cap. The sanctioning coalition’s embargo on seaborne crude left Russia with no choice but to expand trade with Asia. China and India, which were not parties to the price cap, became the primary export destinations for Russian oil. China, already a major market for Russian crude, continued to import large quantities, with average imports worth $171 million per day in 2024. India’s import of Russian crude exploded from virtually zero to $144 million per day on average in 2024.4 The lack of alternative buyers gave these countries increased market power over Russia, allowing them to pay prices that, while above-cap, were substantially discounted relative to before the invasion.5 As a result, a wedge was driven between the price of Russia’s Urals crude oil and the Brent crude oil (a blend of crude oil extracted in Europe and a popular benchmark for global crude oil prices) of other exporters. Though historically tracking closely, the prices of Brent and Urals oil diverged by as much as $30 per barrel after the implementation of the price cap. This wedge has since declined and averaged just under $12.50 per barrel in October 2025. In November 2025 the wedge spiked to around $23 per barrel and in December rose further to an average of nearly $27 per barrel.

The main cause of the narrowing in the Brent-Urals wedge has been Russia’s rapid accumulation of a “shadow fleet” of oil tankers lacking reputable, coalition-provided insurance. These vessels have allowed Russia to increasingly evade the price cap. Beginning at only around 100 ships in March 2022 (since Russia has long needed a means of moving its oil covertly to some extent), the shadow fleet has since expanded by approximately seven ships per month to nearly 350 ships by March 2025. Shadow fleet ships account for over 60% of Russia’s crude oil export volumes in the Baltic. These vessels are often much older than tankers in the mainstream global tanker fleet, with an average age of 19 years compared to the global average in 2025 of just over 14 years. Shadow fleet tankers also frequently adopt flags of convenience from such unscrupulous flagging states as Sierra Leone, Panama, and Cameroon. These flagging states are notorious for rarely enforcing insurance requirements or rigorous safety standards.6

Shadow fleet vessels’ advanced age and poor repair make them vulnerable to mechanical failures and catastrophic leaks. As things stand, a serious disaster is a matter of when, not if—there have already been close calls and smaller-scale spills. And shadow fleet ships’ lack of insurance means that, should a spill occur, European states could be forced to pay for the cleanup out of their own budgets, creating a fiscal crisis. Cleanup costs could easily run into the billions of dollars, even without taking into account the environmental harm and economic disruptions caused by a spill.

II. Options for reform

Sanctioning authorities have a wide range of options for ratcheting up sanctions-based pressure on Russia. From the outset, however, it is critical to specifically define the objectives of any additional sanctions actions. Sanctioning authorities must decide whether their goal is to preserve the volume of oil exported by Russia but to control the price—similar to the price cap framework outlined above—or to curtail the volume of Russian oil traded on global markets—analogous to the approach taken by the U.S. against Iran. The risk of the former option is that it may be ineffective: Inconsistent enforcement leads to limited pressure on price, even while Russia effectively trades without limit. The risk to the latter approach is that it may excessively disrupt energy markets: The sanctions effort could reduce the global supply of traded oil and prices could spike, not only harming consumers and businesses worldwide but also raising the profitability of the remaining Russian exports.

Shadow free zone: A promising regulatory option is simply reducing the size of the shadow fleet. One idea, advanced by Harvard University scholar Craig Kennedy, is to transform the Baltic Sea into a “shadow-free” zone.” In a May 2024 essay, Kennedy observed that tankers in Russia’s shadow fleet typically lacked reputable insurance—a situation facilitated by lax flag state oversight. To render the shadow fleet inoperative while also promoting more comprehensive insurance coverage, Kennedy proposed a voluntary insurance verification program. Here, tanker owners would publicly disclose their insurance status on a virtual industry platform, while insurers (and re-insurers) would simultaneously post their financial statements in line with International Maritime Organization (IMO) practices. Tankers refusing to comply with this voluntary verification would be immediately sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) and other enforcement agencies.

A shadow-free zone in the Baltic would help dissuade Russia from expanding its shadow fleet. In particular, the approach—if adopted by U.S. policymakers—would introduce incentives for tankers to carry legitimate insurance while also developing an automatic mechanism for sanctioning shadow fleet tankers. Additional tanker sanctions would be a welcome outcome given the absence of U.S. tanker sanctions under the Trump administration. However, this proposal risks promoting unintended outcomes. One possibility is that the additional sanctions have little to no effect—but this is unlikely, since U.S. blocking orders coincide with large declines in tanker export volumes. A more probable outcome is that the numerous newly sanctioned tankers have a sharp cooling effect on shipping activity, leading to a reduction in global supply and a concurrent rise in price. This higher price would offset some, or possibly all, of the revenue loss associated with reduced volumes.

Tariffs on Russian oil purchasers: A second option is to issue tariffs on the products imported by purchasers of Russian oil. This approach was undertaken in part by the United States in implementing the 25% secondary tariff on India as retribution for the import of Russian crude. This tariff was levied on top of the Trump administration’s reciprocal tariff and was subject to a host of exemptions. 7(The secondary tariff went into effect on August 27, 2025.) In addition, one recently proposed Congressional bill aimed to introduce tariffs of 500%—equivalent to an embargo—on any country importing Russian oil.8

This well-intentioned approach has several shortcomings. To start, tariffing India for purchases of Russian oil did not immediately appear to have an impact on Indian imports. Just the opposite—India increased imports of Russian oil the month after the imposition of the tariff. Moreover, the application is inconsistent: Other buyers of Russian oil (namely China and to a lesser extent Türkiye and Singapore) do not face tariffs for their purchases, and neither do the dozens of countries that import oil products from Russian refineries. Lastly, as with the shadow-free zone strategy, this approach could potentially shut-in some Russian supply, which would boost global prices and potentially raise revenues for Russia depending on the magnitude of the shock.

Sanctioning Russian oil companies: A third option is to sanction individual Russian oil companies. This was the approach taken on October 15, 2025, by the U.K. when it sanctioned Russian oil producers Rosneft and Lukoil. The U.S. Treasury joined the U.K. shortly after, announcing sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil on October 22, 2025. Under these sanctions, Western service providers—including financers and insurers—were prohibited from doing business with these companies. The sanctions implemented by the U.S. also applied to subsidiaries of these companies, and the U.S. threatened foreign companies that engaged with the targeted Russian firms with secondary sanctions. The ban was set to go into effect on November 21, but the deadline was extended to February 28, 2026. These two companies account for over half of Russia’s oil production.

The initial market reaction to the U.S. announcement was a moderate jump in the price of crude oil of more than 6%, although the increase has since subsided and global oil prices hit 12-month lows in December 2025. At the same time, the spread between Ural crude and Brent crude appears to have widened in the wake of the announcement, rising from around $12 per barrel in October to over $26 per barrel by December of last year. In addition, company-specific sanctions may have induced fire sales, as Rosneft and Lukoil have apparently begun to seek buyers for their assets. For example, Reuters reported that Exxon is in talks to purchase Lukoil’s majority stake in the West Qurna 2 oil field in Iraq. Reuters also reported that the U.S. private equity firm Carlyle was attempting to purchase a large share of Lukoil assets. With the sanctions not yet in effect, the ultimate impact remains unclear.

In our view, these approaches—especially the incremental tariff on India and the sanctioning of Russian oil companies—will probably help reduce Russian revenue at the margin but will likely fall short of pressuring Russia to end its war on Ukraine. A better European sanctions option is needed. Any successful approach will have three primary elements and will require threading a difficult needle. First, it will largely preserve the flow of Russian oil. This goal may seem counterintuitive, but lower global volume will push up profits on Russia’s remaining exports, providing a windfall gain that could even exceed the lost profits associated with the volume cut. Second, it should direct as much of the Russian oil trade as possible back into Western services, where sanctioning authorities can control the price. Third, the sanction framework should discourage the operation of poorly maintained, aging tankers that will inevitably cause an oil spill—and will have no reputable insurance to help cover the cost when they do.

Demanding adequate insurance by regulating flag states, not just tanker operators: Here we suggest a fourth plausible alternative, which was introduced by the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) and is similar in spirit to the shadow-free zone proposed by Kennedy. KSE proposes that a coalition of coastal states in the Baltic, North, and Mediterranean Seas assert “jurisdictional authority” to protect their coastlines from potential oil spills by demanding adequate insurance—backed with binding enforcement mechanisms. The key benefits of the KSE proposal, which we will model in section IV, are that in addition to increasing the share of oil tanker voyages that are covered by sufficient insurance, the very act of conditioning passage on adequate insurance effectively demands that tankers comply with the price cap provisions since no reputable insurer would offer coverage to noncompliant tanker operators. Importantly, the KSE plan would have broader coverage because its centerpiece would be to hold not just tanker operators liable for the insurance requirement but also disreputable flag states that provide legal cover for evading companies.

Shifting liability to flag states is a critical element under this plan. As Part III below explains, maritime law surrenders a great deal of oversight discretion to these flag states, yet a subset of flag states do not seriously embrace their role in enforcing maritime laws and regulations—and those states are often the most popular flags of convenience. Thus, the regulatory linchpin to this plan would be to increase pressure on these states to dissuade them from practicing lax regulatory oversight while simultaneously holding them accountable in the event an aging tanker with inadequate insurance is involved in a spill. To do this would entail two regulatory steps:

- Insurance disclosure requirements: The first step in the KSE plan is to establish requirements around oil spill (P&I) insurance disclosure. This disclosure would be required for any tanker passing through designated areas including the Gulf of Finland, the Danish Straits, the English Channel, the Strait of Gibraltar, and the Aegean Sea.9 At the same time, insurance providers would also be required to document their financial status by releasing three years of audited statements and verification of a satisfactory credit rating, in addition to disclosure of adequate third-party insurance.

- Requiring adequate insurance: The second pillar in the KSE plan would be to enforce the requirement that tankers carry adequate insurance. This step includes four strategies.

- Diplomatic pressure: One, that the coalition of coastal European states exert diplomatic pressure of flag states to verify the adequacy of insurance for vessels carrying their flags. Diplomatic pressure would also be applied to ship classification entities (such as the Indian Register of Shipping) charged with developing and maintaining technical standards.

- Operator liability: Two, KSE recommends all entities involved in tanker operations—such as flag registries, certification societies, and ship owners and charterers—be held liable in the event of a spill.

- Sanctions for underinsured: Three, in line with Craig Kennedy’s proposal, the KSE plan would automatically sanction those vessels which are deemed to operate without sufficient insurance.

- Secondary sanctions and physical intervention: Lastly, KSE notes that physical interference may be justified in “extraordinary circumstances,” such as potential harm to the environment or threat to maritime safety. Here, depending on the specific location of the vessel, coastal states should intervene to secure the tanker in especially threatening situations. In a departure from the KSE proposal, we offer an extension on this final point: Sanctioning authorities—namely the EU, U.S., and U.K., but also other G7 entities—should consider the application of secondary sanctions to deter countries from offering flags of convenience. We also recommend that flag states institute age cutoffs for flagged vessels, as Panama did in August 2025.

The obvious question is whether the KSE plan would be both effective and lawful under domestic and international law. In the next section, we elaborate on the legal justification for the KSE plan and cite various authorities confirming the legality of the approach. The penultimate section models the economic and fiscal impact of such an approach and explains why it would be effective.

III. Legal analysis

The KSE proposal would demand documentation of adequate insurance, including audited insurer finances and reputable international credit rating. Under current practice, Russian insurers very likely could not fulfill the credit rating requirement. Thus, the goal of greater insurance compliance could be enforced if states and insurers pressured flag states to: (1) verify insurance, (2) expand liability for spills to anyone who enabled insurance noncompliance, (3) sanction non-compliant ships, and (4) interdict ships posing immediate danger. To do so would be consistent with Russian, U.K., and EU coastal states’ legal commitments under: (1) general treaties on freedom of navigation as well as (2) specific governing requirements respecting oil shipping insurance.

Treaty law: Russia, Ukraine, and all coastal EU states are party to— and thus obligated to comply with—the key maritime treaties regulating freedom of navigation and specific treaties governing the shipping of oil. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) guarantees the right of innocent passage through other states’ territorial waters but requires ships to follow “generally accepted international regulations, procedures and practices” (GAIRS), a term undefined in the UNCLOS, but which is used in reference to “prevention, reduction and control of pollution from ships,” as regulated by rules established by the competent international organization (p. 37). Under UNCLOS Article 220, states can pass laws to impose GAIRS within their territorial seas but can only stop ships in such waters for lack of adequate insurance if they have “clear grounds for believing” that the ship “violated laws and regulations” while in territorial waters (p. 111).

International administrative regime: States that are party to generally accepted maritime treaties, such as the International Maritime Organization (IMO) conventions, are obligated to follow and enforce regulations and GAIRS set out in those agreements. This system can be described as global administrative law (GAL), the system of administrative rules in global institutions, because the IMO de facto creates binding rules whose implementation and enforcement are generally carried out by the domestic law of states that are regulated by those international bodies.10

A responsible oil tanker must maintain insurance compliant with one of those IMO treaties, the International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (CLC)—likely about $100 million for average shadow fleet tankers. Under the CLC, ships carrying more than 2,000 tons of oil are required to maintain insurance for oil pollution damage that covers the registered owner’s liabilities under the Convention and up to the required financial limit of liability. Because the IMO has no direct enforcement powers, IMO conventions such as CLC are largely enforced by the flag state of the ship as a domestic enforcer responsible for penalizing violations and in some cases certifying compliance. Other states do, however, have some limited enforcement powers when foreign ships are in their jurisdiction. Thus, the CLC directs states to “ensure, under its national legislation” (p. 6) that insurance is in place for ships docking in its territory and, per Article 220, to stop ships they believe are in violation.

International Maritime Organization Circular Letter 3464 provided guidance on insurer standards in light of sanctions on Russian entities, encouraging states to collect information on insurer finances, reinsurance, and independent financial rating. Verification of insurance and financial stability is harder to enforce due to credit rating withdrawals from Russian markets and obstacles to inspection posed by the UNCLOS right of innocent passage. But it seems likely that most Russian maritime insurance currently violates the GAIRS standard because those ships: (1) do not use insurers from the IG P&I Clubs and (2) likely have insufficient reinsurance.

Ukraine-specific international law: Since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, resolutions have been adopted that were designed to apply these generalist international law frameworks to increase cooperation on actions addressing the specific challenges posed by the Russian shadow fleet. This kind of international cooperation to enforce IMO obligations in a specific case constitutes what is known in general international law as a “lex specialis,” which in this case governs the particular Russia-Ukraine issue. Once again, such lex specialis enforcement in this area has been done lawfully but not fully effectively. While there are many UN General Assembly resolutions backing Ukraine in its resistance to Russian aggression, none of this “lex generalis” contains language specifically directing or obligating member states to take actions against the shadow fleet. As a matter of international law, there are currently no UN resolutions that could be used to argue that states have a specific legal obligation to act against the shadow fleet.

The most prominent call to action dates from March 2022, shortly after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Crimea. That General Assembly resolution “[c]alls upon Member States to fully fund the United Nations Humanitarian Response Plan 2022” (p. 4). On December 6, 2023, the International Maritime Organization (itself an agency within the UN) issued a resolution defining the “shadow fleet” as those “engaged in illegal operations for the purposes of circumventing sanctions [and] avoiding insurance costs” and encouraging port states to ensure “that ships have on board valid State certificates of insurance, in accordance with the IMO liability and compensation conventions” (p. 3). The IMO’s guidelines for flag states to evaluate the adequacy of non-IG spill insurance further include (1) a review of three years of the insurer’s audited financial statements and (2) the submission of a satisfactory credit rating report from a reputable international rating agency.

Unfortunately, the IMO rules, standing alone, seem to set inadequate requirements of marine insurance for Russian oil shippers. The issuance of guidelines has thus not solved the problem, most likely because of willful negligence by certain flag states. As the expanding shadow fleet generates growing demand for tankers that are not insured by the International Group of P&I Clubs and do not comply with sanctions, the problem seems to be getting worse rather than better.

Relevant domestic law: As is often the case, the prime legal enforcement mechanism for these international legal rules is not horizontal enforcement by nation-states directly against one another but “vertical enforcement” through internalization of these obligations into domestic law, what one of us has long called “transnational legal process.”11 Leading IMO conventions impose on their member states obligations to adopt laws or regulations necessary to give IMO conventions full force.

The U.K., for example, has done this by passing “ambulatory” laws in Parliament that give IMO conventions and amendments direct effect in U.K. law. In the MSC Mediterranean Shipping Company case (2025) the U.K. Supreme Court acknowledged that an IMO convention was the law that controlled in the case. Although the relevant convention in this case was not the CLC, both the relevant IMO convention and the CLC were incorporated into U.K. law in the Merchant Shipping Act. The majority of EU members and all coastal members are party to the CLC. Similarly, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has held that while the European Community is not a party to the CLC, EU law must be interpreted to avoid conflicts with IMO conventions to the maximum extent possible in order to prevent member states from having conflicting European and international law obligations.

Thus, the prime enforcement device for enhanced insurance requirements for the Russian shadow fleet would come through a universal change to GAIRS in response to this issue, which has implications beyond the conflict in Ukraine. That amendment could then be internalized into the domestic maritime insurance laws of the states to which most vessels carrying Russian oil are flagged. Compliance with such international law “lex specialis” would not entirely preclude legal challenges to those requirements under the domestic laws of the enforcing states, but it would vastly reduce the likelihood that those legal challenges would succeed.

Two questions thus remain. First, what economic impact would enhanced marine insurance requirements have on the current volume of Russian oil being trafficked by the shadow fleet? Second, what legal changes would best bring about those meaningful economic changes?

IV. Economic analysis

Our model employs departure-level crude oil export data obtained using the Bloomberg Terminal’s AHOY function. This initial dataset includes vessel IMO number, vessel capacity in cubic meters, and vessel class for all crude oil export voyages from Russian ports with departure dates from January 1, 2025, through June 30, 2025. We supplement AHOY data with information on vessel ages taken from the Bloomberg Terminal’s IMO function as well as historical flagging data obtained from the IMO’s Global Integrated Shipping Information System (GISIS) Ship and Company Particulars database. We convert cubic meters to barrels using a standard multiplier of approximately 6.29 barrels per cubic meter of oil. We determine shadow fleet status based on information from multiple external sources, including the Ukrainian government, Kyiv School of Economics, and the U.S. Treasury. To facilitate our calculation of export values and total revenues, we purchase daily Baltic Urals price data from Argus Media.

Our total dataset contains 714 crude oil export voyages taken by 373 unique ships, cumulatively transporting around 568 million barrels of Urals crude. In this paper we confine our analysis to departures from the Russian Federation’s two primary Baltic ports, Primorsk and Ust-Luga. Our baseline dataset encompasses 333 individual crude oil export voyages taken by 228 unique ships, cumulatively transporting 263 million barrels of Urals crude oil, worth $15.0 billion, over the first half of 2025. This represents over 30% of Russia’s total crude exports during the sample window.12 In our six-month Baltic dataset, 229 voyages departed from the port of Primorsk, while 104 departed from Ust-Luga. Each port saw a proportional percentage of voyages and export volumes—voyages from Primorsk made up approximately 69% of both voyages and export volume, and voyages from Ust-Luga were 31% of both voyages and volume.

Out of the total of 333 voyages, 65% (217) were taken by 146 unique shadow fleet ships (64% of unique ships). The 82 unique ships in our dataset that were not in the shadow fleet accounted for 35% of voyages and 36% of unique vessels. Shadow fleet vessels transported 63% of total seaborne Baltic crude oil exports, while ships not in the shadow fleet moved 37% of total volumes. Shadow fleet vessels tended to be smaller than ships not in the shadow fleet, with an approximate mean capacity of 760,000 barrels compared to the non-shadow-fleet average of roughly 850,000 barrels. The most common tanker class among ships both in and out of the shadow fleet was the Aframax class. Notably, however, Aframax tankers made up a larger percentage of the shadow fleet (80 out of 146, or around 55%) compared to their share of non-shadow-fleet ships (35 out of 82, or roughly 43%). Larger Suezmax class tankers were more common outside of the shadow fleet, comprising 39% of non-shadow-fleet ships but only 17% of shadow fleet ships. The mean age of shadow fleet ships in our dataset was 19.0 years old, much higher than the average of 12.4 years for ships outside the shadow fleet.

In addition to the distinction between shadow fleet and non-shadow-fleet vessels, we also distinguish between price cap compliant and price cap noncompliant voyages when making our export value calculations. The noncompliant voyages category includes ships in the shadow fleet; ships sailing with false flags according to the IMO at the time of a voyage; and ships that were already sanctioned by the U.S., U.K., or EU at some point before voyage departure. We calculate that noncompliant voyages, which could trade Russian crude oil at market prices above the $60 per barrel limit, moved 165 million barrels of crude oil for a cumulative value of $9.5 billion. In contrast, compliant vessels moved 98 million barrels with a total value of $5.5 billion. As a result, non-cap-compliant vessels were responsible for approximately 63% of total export value and volume, while compliant vessels made up 37% of total value and volume. 13 The lack of spread between the percentages of value and volume carried by compliant vessels stems from the fact that the market price of Baltic Urals crude oil fell below the $60 per barrel cap for significant portions of our six-month sample period. If the price cap were binding as intended, we would expect the percentage of exports by value carried by cap compliant voyages to be lower than the percentage of exports by volume.

The flagging status of voyages in our sample is a central focus of our model. Based on data from the IMO, we identify 32 different flags flown by vessels in our model (including false flags as separate categories from the nation they claim to be).14 The most common flags were those of Panama, with 80 voyages flagged; Liberia, with 54 voyages flagged; Greece, with 26 voyages flagged; Barbados, with 23 voyages flagged; and the Marshall Islands, with 20 voyages flagged. Together, these five flags account for over 60% of voyages in our Baltic sample. Of the voyages flagged by Panama in our model, we estimate that 74 were noncompliant. Liberia flagged 21 noncompliant voyages in our model, while all 23 of the voyages flagged by Barbados in our model were noncompliant. Only two voyages flagged by the Marshall Islands were noncompliant in our model, and no Greek-flagged voyages were noncompliant. In addition to Greece, the flag states with no noncompliant voyages in our model were Azerbaijan, Malta, Türkiye, and the Bahamas with 14, 13, three, and two flagged voyages, respectively.

To estimate the impacts of various levels of price cap and sanctions reform, we assume that stricter enforcement of insurance requirements and sanction status by flag states, as well as by coastal states in the sanctioning coalition, will result in crude oil shifting from noncompliant to compliant voyages, as well as some tankers dropping out of the Baltic oil trade altogether. Given the short-run limit on the global supply of crude oil tankers, in some scenarios we predict a reduction in the volume of oil exported by Russia to global markets and consequently that global oil prices will rise to some degree. This may increase the value of Russian oil exports through other regions, offsetting losses in revenue from Baltic exports.

Russia’s oil and gas tax revenues are primarily based on extraction taxes. This means that the value of crude oil exports is only indirectly related to the amount of tax revenue the government receives, and the effective tax rate varies a great deal. The private sector is responsible for moderating extraction levels to account for market conditions and tax obligations. In our model we assume that 40% to 60% of export value is received by the Russian federal government as revenue.15

We assume that flag states fall into four different levels of “reliability” in deflagging sanctioned vessels and implementing insurance requirements. These levels are “reliable,” made up of nations that already maintain high standards; “reachable” states that are susceptible to mild diplomatic pressures from the international community; “stubborn” flag states that might require the threat of secondary sanctions and liability for damages caused by uninsured flagged vessels; and “unreliable” flag states are unlikely to comply except in the face of extreme economic pressure or the interdiction of voyages that violate international standards. We divide flag states into these categories primarily based on the percentage of compliant and noncompliant voyages they flagged over the sample window of our model. Reliable states, such as Greece and Malta, had zero noncompliant voyages in our dataset. Reachable states had a mix of compliant and noncompliant voyages—spanning from 90% compliant for Marshall Islands-flagged voyages to only 7.5% compliant Panama-flagged voyages. Stubborn flag states, such as Sierra Leone and Barbados, had only noncompliant voyages. The unreliable flag state category, which also had exclusively noncompliant voyages, contains voyages that were falsely flagged, directly flagged by the Russian Federation, or had an unknown flag.

In addition to our baseline—the results of which are discussed earlier in this section—we simulate four scenarios that model the impacts of our proposed sanctions reforms if they had been implemented before January 1, 2025.16 The first scenario is an altered baseline, with no additional enforcement but an earlier implementation of the current U.K. and EU price cap of $47.60 per barrel. This scenario leaves export volumes unchanged but reduces total export revenues to $14.1 billion. Compliant export values fall from $5.5 to $4.7 billion, while noncompliant export values remain the same. Global crude prices are also unchanged. We estimate that Russian federal tax revenues from Baltic crude oil exports decline by 5.6% in scenario one.

The second scenario keeps the lowered price cap and sees diplomatic pressure exerted on reachable flag states before the beginning of the year, incentivizing more rigorous enforcement of maintenance and insurance standards and the deflagging of noncompliant vessels.17 Under this scenario, compliant exports increase dramatically to 172 million barrels, worth $8.2 billion. Noncompliant crude oil export volumes decline to 91 million barrels, causing the value of noncompliant exports to fall to $5.3 billion. Federal tax revenues from Baltic crude oil decline by 10.4%.

The third scenario introduces the threat of secondary sanctions and liability damages caused by flagged vessels. Under this scenario, stubborn flag states are also incentivized to enforce insurance requirements.18 Though this incentivizes greater export of oil through cap compliant pathways, it also causes some tankers—and their cargo—to drop out of the oil trade, reducing total Baltic export volumes to 240 million barrels. Despite a global price increase of 1.9%, noncompliant exports decline to a value of $3.0 billion. With compliant export volumes rising to $10.1 billion, total exports are worth $13.1 billion. Federal tax revenues from the Baltic crude oil trade consequently fall by 12.7%.

The fourth scenario ratchets up the pressure on noncompliant shipments even further, introducing the possibility of physical interventions on vessels that violate international law by failing to comply with flagging and insurance requirements.19 This would force vessels flying false or unknown flags to cease shipments until they can operate legally, driving a further reduction in total volumes to 235 million barrels, causing global prices to increase by 2.4%. Compliant voyages account for the vast majority of this volume, carrying 230 million barrels worth $11.0 billion. Noncompliant voyages dwindle to 5 million barrels worth only $1.9 billion, bringing total export values to $12.9 billion. In scenario four, Russia’s Baltic crude oil tax revenues are reduced by 14.0%.

An important caveat to our analysis is that our data are retrospective; the current flagging status of the Russian Baltic fleet has evolved since June 30, 2025. Some of the states that flagged noncompliant vessels in our dataset have already taken steps to raise standards for flagged vessels, and reign in sanctions evasion. These include Gambia and Comoros, which were both in the “stubborn” category in our model. Looking at Bloomberg IMO data from mid-December 2025 on the flagging status of vessels in our model, Sierra Leone is now the most common flag state, flagging 36 of the 228 vessels in our sample. Significantly, all vessels flagged by Sierra Leone are in our shadow fleet database. Panama and Liberia remain major flag states, respectively flagging 27 and 30 vessels. However, while 24 of the Panama-flagged vessels are in the Baltic shadow fleet, only eight shadow fleet vessels in our Baltic sample are using the flag of Liberia—supporting the claim that the Russian tanker fleet was already in the process of moving away from Liberia in early 2025. Following Sierra Leone and Panama, Cameroon was the third most common flag for shadow fleet vessels, flagging 10 vessels in the shadow fleet. Finally, 27 vessels in our sample were falsely flagged according to the December 2025 data. It is vital that persistent pressure be exerted on all flag states to prevent shadow fleet ships from continuing to flee to more permissive registries.

V. Conclusion and recommendation

As a matter of policy, the Kyiv School of Economics’ proposed approach to strengthening sanctions against the Russian oil trade would be effective, politically achievable, and legally available. To realize this approach, we recommend that the U.K. and European states coordinate to implement universal changes to GAIRS to ensure that shadow fleet ships carry sufficient insurance. This approach would require modest revisions in domestic law to close the existing loopholes in the GAIRS that allow shadow fleet ships to operate in Europe while underinsured. While further international law changes are not necessary, an IMO resolution changing the GAIRS could help to hold noncompliant ships responsible. A well-drafted universal change would make it harder for ships to flee to more permissive flag state registries. European allies could implement changes, potentially through executive or legislative action changing domestic law. Quick adjudication, particularly before the U.K. courts and then the European Court of Justice, would then likely confirm the domestic legality of these stricter insurance requirements.

We find that such legal and administrative reforms would have marked impact on Russian oil trade out of Baltic ports. Retrospective modeling of Russian exports from Primorsk and Ust-Luga over the first half of 2025 estimates that this approach could shift Russia’s oil trade away from noncompliant tankers towards compliant tankers that adhere to European law and regulations. Under a scenario with these reforms and relatively weak enforcement, our simulations indicate that the share of oil traded by compliant vessels rises from just over one-third (37.4%) to just under two-thirds (65.3%), with no change in export volume or global oil price. Under an aggressive enforcement approach, the share of noncompliant exports approaches zero (2.0%) with a 10.6% reduction in the volume of Russian oil exports out of Baltic ports and 2.4 percentage point increase in global oil prices. These reforms would reduce Russian tax revenue from the Baltic oil trade by between 5.6% and 14.0%, with the impact increasing with the strength of enforcement.

In sum, the KSE proposal offers a realistic option for Europe to stiffen pressure on Russia to withdraw from Ukraine and reach a peaceful resolution to the illegal war. Per the proposal, the U.K. and EU member states should push flag states to more frequently adhere to international shipping regulations and guidance. The best way to do so would be by requiring insurance disclosure and enforcing insurance standards through diplomatic pressure, flag state liability, sanctions for underinsurance, secondary sanctions, and physical intervention when it becomes plainly necessary. Coordinated, targeted, and legally tighter actions against the shadow fleet from the U.K. and Europe would strengthen Ukraine’s hand in future negotiations and improve the chances of achieving a just and sustainable peace.

-

Footnotes

- “The Russian economy and world trade in energy: Dependence of Russia larger than dependence on Russia,” Oesterreichische Nationalbank.

- EU imports of Russian oil fell from 3.5 million barrels of oil per day in 2021 to 0.4 million barrels per day in 2024.

- One study puts crude oil’s price elasticity of demand at approximately –0.14, and another puts it at –0.18. In our calculations we use an elasticity of –0.15 as a middle ground. Mimicking the assumptions made about the oil market in Wolfram, Johnson, and Rachel (2022), we calculate that a 10% reduction in crude oil supply would raise prices by 67% ((–0.10)/(–0.15) = 0.667).

- Calculated using United Nations Comtrade data.

- Despite their advantageous position in the Russian oil trade, China and India may decrease imports of Russia oil following the U.S. sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil in late October 2025.

- See Erausquin and Keatinge (2025), Feng, Dalton, and Kiss (2026), and Braw (2024).

- The Trump administration has introduced a number of exceptions to the reciprocal tariffs levied against India and other nations. Exceptions include those on steel, aluminum, and copper; timber and lumber; and on agricultural goods such as coffee, tea, fruit juice, spices, and beef.

- Introduced by Lindsey Graham (R-SC) in April 2025, the Sanctioning Russia Act of 2025 would require that the president impose 500% tariffs on countries that knowingly purchase oil products and uranium from Russia.

- KSE notes that this is feasible in practice, as “Mainstream vessels already routinely do this through Equasis, a multilateral, open-access database dedicated to safety in the shipping industry,” (p. 16).

- Global administrative law emerged from the increase in transnational regulations created by international regulatory bodies. This led to the emergence of administrative standards for process, transparency, and accountability in particular issue areas. See generally Benedict Kingsbury et al., The Emergence of Global Administrative Law, 68 Law and Contemporary Problems 15-62 (Summer 2005).

- Harold Hongju Koh, Transnational Legal Process, 75 Nebraska L. Rev. 181 (1996); Harold Hongju Koh, The Yale School of International Law, Yale J. Int’l L. Online (Sept. 22, 2024).

- Calculation was performed using data on annual average crude oil exports from the 2025 Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) Annual Statistical Bulletin.

- The percentages for noncompliant and compliant voyages are very similar to those of the shadow fleet and non-shadow-fleet, respectively, because all ships that were sanctioned or flying false flags were already in our shadow fleet list. We use the expanded “noncompliant” category for completeness’ sake.

- It is important to note that flagging data from the IMO only identifies the month in which a new flag went into effect. In our analysis, we assume that new flags were effective on the first of the month rather than at some other point in the month.

- This range of effective tax rates is based on our own calculations as well as conversations with industry experts. In our calculations, we divided oil-related tax revenues reported by the Russian Ministry of Finance by total oil export value from monthly International Energy Agency oil market reports. Given that Russian government reports of their own fiscal situation are inherently unreliable, we present effective tax rate as a range to reflect this uncertainty.

- The second, third, and fourth scenarios are simulated by randomly dividing each reliability level with noncompliant voyages into four groups of equal or near-equal voyage count (12 groups total). We then have some of these groups of voyages either become compliant or drop out of the oil trade depending on the scenario. To account for the effect that variability in vessel sizes and export dates would have on the total export volumes and values of each randomly created group, we run this simulation 10,000 times and then average the export volumes, price impacts, and export values of each scenario across iterations.

- In scenario two, we assume that 75% of noncompliant voyages flagged by reachable flag states become compliant, while 25% remain noncompliant. Furthermore, 25% of noncompliant voyages flagged by stubborn states become compliant, leaving 75% noncompliant. There is no change to the behavior of voyages flagged by unreliable flag states in this scenario.

- Our third scenario assumes that 100% of noncompliant voyages flagged by reachable flag states become compliant. We additionally model that 50% of voyages with flags from stubborn flag states become compliant, while 25% remain noncompliant and 25% drop out of the oil trade (meaning a voyage does not occur). Scenario three assumes that 25% of noncompliant voyages flagged by unreliable flag states become compliant, 50% remain noncompliant, and 25% drop out.

- In scenario four, we model again model that 100% of noncompliant voyages flagged by reachable states become compliant. This scenario sees 75% of noncompliant voyages using stubborn flag states become compliant, while 25% drop out of the oil trade. Finally, 25% of unreliably flagged voyages become compliant and 50% drop out, leaving only 25% noncompliant.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).