Executive summary

Situated at the intersection of the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers, the Southeastern Pennsylvania region—comprised of Philadelphia and the surrounding Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery counties—represents one of the oldest and the largest metropolitan economies in the United States. Nearly 350 years after its establishment as a colonial center for global trade, agriculture, early manufacturing, and shipbuilding, the region is now viewed as a national hub for life sciences, health care, education, and professional services.

However, despite years of job growth, Southeastern Pennsylvania has experienced challenges in competing with high-performing peers such as Atlanta, Boston, and Phoenix. In particular, the region’s tradeable industries (those that sell goods and services beyond the region’s borders) failed to keep pace with national growth in recent years, therefore not fulfilling the region’s productive potential and stifling wage growth. Had Southeastern Pennsylvania’s tradeable industries matched their national performance, the region would have added over 104,000 more jobs between 2013 and 2023.

This jobs deficit has proven immensely consequential for the region’s workers. Of the 104,000 jobs that Southeastern Pennsylvania would have added if it had kept pace with the nation, 70% would have been expected to offer opportunity for workers to support themselves and their families. Additionally, as growth in industries such as manufacturing and wholesale has eroded, Southeastern Pennsylvania’s economy has become increasingly reliant on growth in non-tradeable (“locally serving”) industries such as health care and hospitality, coupled with mild tradeable industry growth in advanced sectors such as financial services, where jobs disproportionately require a four-year degree. As a result, the regional labor market has become increasingly split down the middle between high-wage and low-wage jobs, with pathways into the middle class becoming increasingly scarce, particularly for workers without a college degree.

The region’s capacity to respond effectively is limited by structural challenges. Southeastern Pennsylvania is one of the most jurisdictionally fragmented areas in the country, yet its economy is highly integrated with shared industry strengths, workforces, innovation assets, and infrastructure that cross political boundaries and institutional responsibilities. Meanwhile, the region lacks a unified, tactics-level strategy and workplan to guide economic and workforce development efforts. This absence hinders the ability of stakeholders to prioritize, align, and coordinate actions for maximum collective impact. In contrast, leading peer regions rely less on public sector program delivery and more on business-led initiatives that offer greater flexibility and long-term commitment. These peers also benefit from significantly better resourced regional economic development organizations, supported by clear operating agreements that define roles and relationships among partners for centralized or distributed functions.

In light of these challenges, Southeastern Pennsylvania leaders must align behind a shared strategy that leverages the region’s immense economic, innovation, and human capital assets to create more middle-class jobs in industries where the region is well positioned to compete in the global economy. Growth trends over the past decade as well as qualitative engagement with business leaders and economic developers across the five-county region reveal three key industry clusters through which Southeastern Pennsylvania can chart this new path forward:

- Enterprise digital solutions: Business-to-business software tools and customization services to optimize back-office and middle-office functions in operations, compliance, and strategy (such as “Business Process as a Service” and “Integrated Platform as a Service”), where historic regional strengths in technologies and regulated sectors converge to spur applications for a range of both service and manufacturing industries. Example firms: SAP, Boomi, SEI, Qlik, Citco, EPAM, Envestnet, InstaMed, Savana, Guru

- Materials machining/fabrication and electronic components value chain: Production and distribution of precision metalworking and polymer components, industrial and process equipment, high-tolerance electronic connectors and instrumentation, communications systems and control devices, and related assemblies, anchored by small- and middle-market firms. Example firms: TE Connectivity, R-V Industries, Nicomatic, Rhoads Industries, Teledyne Judson Technologies, Acero Precision

- Biomedical commercialization: Manufacturing diagnostics and therapeutics (including biologics) and medical devices—continuing a shift in emphasis from research and emerging technology platforms such as cell and gene therapy, as well as retaining more life science startups through early and growth stages. Example firms: Janssen Biotech, Iovance, Globus Medical, GlaxoSmithKline, Trice Medical, TELA Bio, Axial Medical, DePuy Synthes

In sum, Southeastern Pennsylvania is strongly positioned to become more economically prosperous, resilient, and inclusive—but leaders in the region must adopt an opportunity-oriented mindset toward future growth and build new capacity for addressing challenges together. This report, which resulted from a multiyear collaboration among Southeastern Pennsylvania economic and workforce development leaders, provides the region with a shared rationale and evidence base on which to act in service of this goal. Through dedicated strategic partnerships, industry prioritization, and alignment between economic and workforce development partners, Southeastern Pennsylvania can chart a new path forward that reaffirms its centuries-long legacy of productivity, innovation, and prosperity.

Introduction

Southeastern Pennsylvania—encompassing Philadelphia and the surrounding suburbs of Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery counties—is a global economic heavyweight. Its world-class universities, cutting-edge laboratories, financial services giants, and other assets support more than 2.7 million jobs1 and generate more than $355 billion per year in output—a level of economic activity that would rank it among the 60 largest national economies in the world.2

However, signs increasingly indicate that the economy has shifted in ways that make it more difficult for the region’s firms to compete and for its workers to get ahead. For instance, landmark research released in 2024 by Harvard-based Opportunity Insights placed Southeastern Pennsylvania at the bottom of the nation’s largest regions in enabling low-income residents the opportunity to advance beyond the previous generation’s economic status.3 The continuation of historic racial inequities and dramatic declines in economic mobility for lower- and middle-income white residents, including in suburban counties, both fed this trend.

These dynamics point to deeper challenges with the region’s growth and job creation engine, which may at first be obscured by its significant assets. Like most older U.S. industrial regions, Southeastern Pennsylvania’s manufacturing economy lost traction in recent decades when matched against lower-cost domestic and international competitors. Since the Great Recession, its professional services edge has also eroded. In turn, the weight of Southeastern Pennsylvania’s economy has skewed away from producing high-value goods and services for sale beyond its borders and toward offering services such as health care and retail predominantly for its own residents, dampening its ability to produce high-paying jobs. While local-serving sectors (such as construction and health care) do contain some high-paying jobs, they concentrate these jobs at lower rates overall, and growth in these sectors is only indirectly influenced by regional economic development efforts.4

These challenges are not unique to Southeastern Pennsylvania. The convergence of technological change and global competition in recent decades has fueled a splitting of the labor market into high-wage and low-wage jobs, with fewer traditionally middle-class opportunities in between. These macroeconomic trends have also drawn clearer lines between a modest set of higher-performing regions with stronger footholds in innovation-, talent-, and technology-driven industries and a broader array of population centers held back by legacy industrial bases, scale, and other competitive deficits.5 Regions that are successfully repositioning themselves amid these headwinds are acting with intention: identifying competitive and emerging regional industry advantages; investing in comprehensive ecosystems of talent development, innovation, commercialization, industry-relevant infrastructure, and governance, which are core to industry success; and taking deliberate action to ensure access and inclusive growth.6

Amid this more competitive landscape, Southeastern Pennsylvania cannot rely on a “business-as-usual” approach to economic development, historically characterized by fragmented efforts across jurisdictions at lower levels of collective investment than many other U.S. regions. Rather, it must align behind a shared, tactics-level strategy with the requisite civic capacity and that links economic and workforce development priorities, which can enable it to maximize its untapped potential and grow more jobs that allow its residents to prosper.

This market assessment is not a research study to spark consideration—it provides regional civic and business leaders with the rationale and evidence base to act. As part of a multiyear collaboration among Southeastern Pennsylvania economic and workforce development leaders (see sidebar), practitioners and supporters reviewed this assessment’s findings, which will inform the development of a shared, tactics-level strategy focused on cultivating the industries and job base needed for a vibrant, inclusive economy.

Southeastern Pennsylvania: An interconnected economy

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, the Pew Charitable Trusts convened Philadelphia civic, business, and government stakeholders to consider how to promote an inclusive recovery. After benchmarking against other places, participants identified greater regional economic and workforce collaboration as an opportunity. In late 2023, Brookings partnered with Pew to explore that concept with leaders in surrounding jurisdictions, leading to the formation of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Economic Collaborative, which consists of organizations in Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Montgomery, and Philadelphia counties, as well as the Chamber of Commerce for Greater Philadelphia, Visit Philadelphia, and the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission. For over a year, this group engaged and expanded to inform development of this analysis, advance shared functions such as economic research and international engagement, and prepare for undertaking a common strategy.

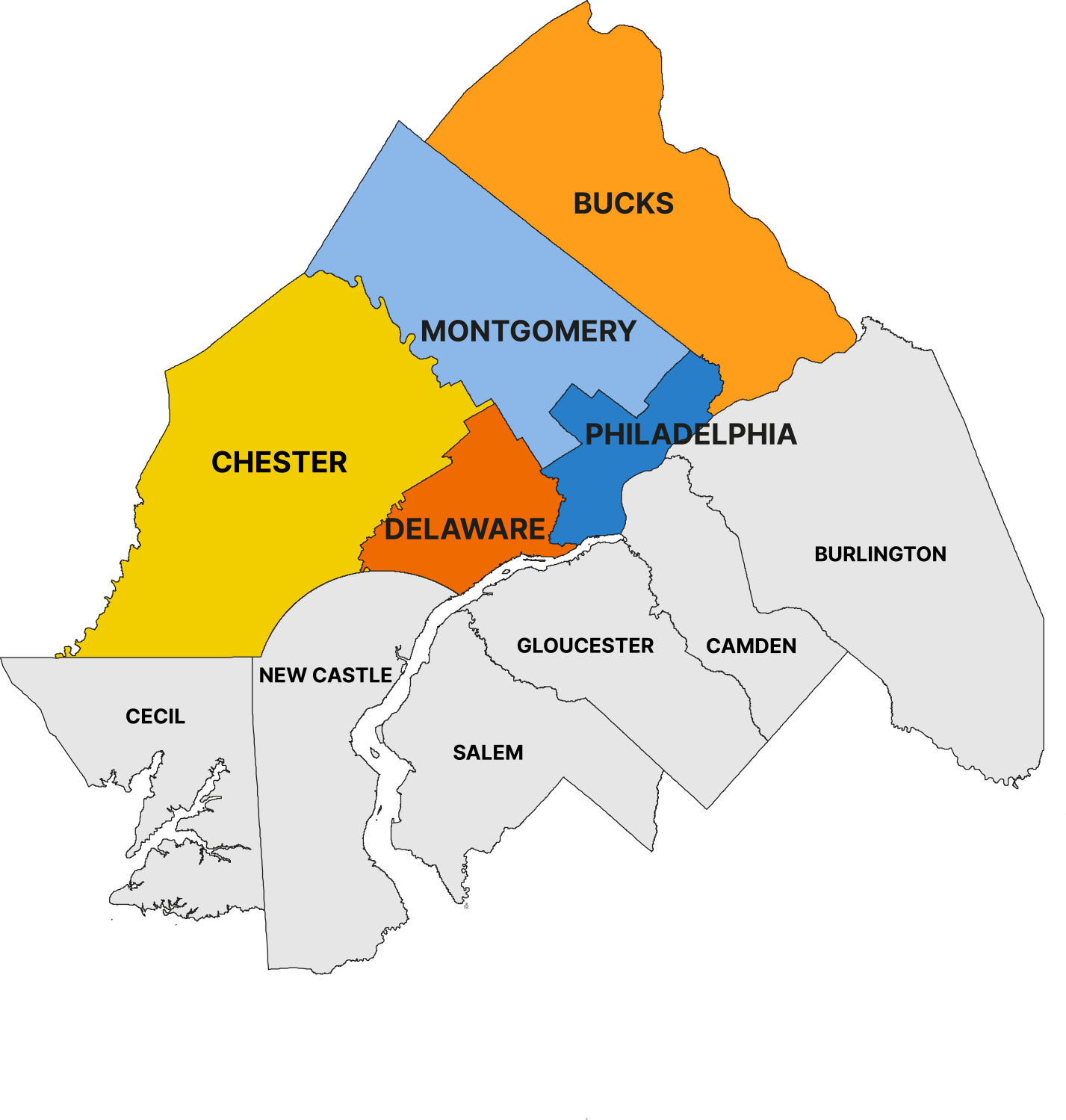

Focusing first on Southeastern Pennsylvania was a practical choice for effective organizing and execution. The full Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington metropolitan statistical area (or MSA, a federally set geography defining a functional economic area) includes additional counties in New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland. However, the five Pennsylvania counties account for 69% of the jobs and 70% of the gross domestic product (GDP) of the tri-state metro area. Working with counties in a single state provides a common base of existing structures and planning requirements, and avoids the added complications of dealing with three different economic and workforce systems with separate policies and funding streams. Furthermore, action in Southeastern Pennsylvania was timely to align with the commonwealth’s new 10-year Economic Development Strategy launched in 2024.

Note: While this market assessment focuses primarily on Southeastern Pennsylvania, portions of analysis presented in the accompanying data book also include breakdowns for the entire MSA, along with the Southeastern Pennsylvania unit and its individual counties.

Working across these jurisdictional boundaries in Southeastern Pennsylvania is imperative to addressing core issues of competitiveness and economic mobility. While Philadelphia is the globally recognized brand, it represents 37% of the region’s population, 35% of its jobs, and 34% of gross regional product, plus the main campus of all three Tier 1 research universities. The surrounding four counties, meanwhile, hold the majority of the region’s jobs in key industries such as financial services, life sciences, and manufacturing; Tier 2 research universities; and community college students. Among residents in Southeastern Pennsylvania, 87% stay within the five counties for work, and 38% cross a county border to reach their job. The five-county region functions as the true economic unit—competing at scale as an integrated system with a shared workforce, industry value chains, and innovation and infrastructure assets that drive their collective economic trajectory.

|

Outbound commuting |

In county |

Outside county, in region |

Outside of region |

|

Philadelphia County |

70% |

19% |

11% |

|

Montgomery County |

61% |

28% |

10% |

|

Chester County |

60% |

23% |

17% |

|

Bucks County |

56% |

25% |

19% |

|

Delaware County |

51% |

36% |

13% |

|

Total, all resident workers |

62% |

25% |

13% |

Despite the value of working at this scale, Southeastern Pennsylvania has often struggled to overcome the commonwealth’s exceptionally high fragmentation of local governments compared to other states and regions. Large metro area peers have significantly greater public-private regional economic development organization capacity, as well as tactics-level written strategies and operating agreements to guide centralized or distributed initiatives. Advancing efforts by the Southeastern Pennsylvania Economic Collaborative, alongside renewed state attention to regional economic action, represents a step toward addressing these gaps.

Economic performance and opportunity in Southeastern Pennsylvania

In many ways, Southeastern Pennsylvania appears to be a region on the rise. The population is growing, and employment is growing with it.7 Economic activity has rebounded in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.8 And prominent economic development organizations, consultancies, and tourism and travel organizations are increasingly highlighting the Greater Philadelphia region as one of the world’s best places to live,9 work,10 visit,11 and open a business.12

The economic progress Southeastern Pennsylvania has demonstrated in the years since the Great Recession—particularly in contrast to its well-documented difficulties of the late 20th century13—is welcome news not just for the region itself, but for the entire commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the U.S. overall. As of 2023, the five counties together would rank as the 14th-largest metropolitan economy in the country, hosting more than 2.7 million jobs and producing more than $355.5 billion in output.14 Nearly 4.2 million people live in Southeastern Pennsylvania, making the region larger by population than nearly half of all U.S. states.15 The region is also indisputably a global innovation powerhouse, spending billions of dollars every year16 on research and development, which has yielded some of the country’s most important innovations of the past century, ranging from the first computer17 to the mRNA technology enabling the COVID-19 vaccine.18

Yet underneath Southeastern Pennsylvania’s rebounded economy is a more complex picture of economic competitiveness and resilience. The composition and trajectory of the region’s economic growth reveal that it is not maximizing the potential of its formidable assets, thus limiting benefits for firms and residents. Brookings Metro analysis of economic growth between 2012 and 2023 determined three central points of tension for Southeastern Pennsylvania’s economy:

- Many of the sectors in which Southeastern Pennsylvania experienced the highest job growth between 2012 and 2023 grew at a slower rate than the nation as a whole, indicating that the gains the region has made have largely been a byproduct of national tailwinds rather than distinct regional competitive advantages.

- The jobs that Southeastern Pennsylvania added between 2012 and 2023 were disproportionately concentrated in locally serving industries, which provide goods and services to consumers within the confines of the regional economy but do little to inject new wealth from outside of the region. Conversely, the tradeable industries that serve as Southeastern Pennsylvania’s anchors into national and global supply chains through interregional trade have been lagging behind. Because tradeable industries have higher productivity and pay higher wages than locally serving counterparts, this stagnation has dampened earnings growth and prevented the region from becoming more productive overall.

- Southeastern Pennsylvania’s competitiveness challenges have contributed to a gap in the “opportunity jobs” (see Key Terms below) that workers rely on to pay living wages, cover health benefits, and offer opportunities for upward economic mobility. In 2023, just half of Southeastern Pennsylvania’s jobs provided this type of economic opportunity to the region’s workers—a lower share than two-thirds of the nation’s other 50 largest metropolitan areas. Research from Opportunity Insights similarly found that children born into low-income families in Southeastern Pennsylvania are less likely than children in any of those other large metro areas to achieve economic stability in adulthood. This suggests that the region’s deficit of opportunity jobs is part of a larger pattern of erosion facing Southeastern Pennsylvania’s working middle class across demographics and geography.

These trends and the factors underlying them represent underperformance rather than decline. They reinforce the need for a stronger regional approach to more effectively leverage the region’s world-class economic, innovation, and human capital assets to generate more accessible opportunities.

About this analysis

This market assessment reviews industry performance in Southeastern Pennsylvania using a method called “shift-share analysis,” which gauges the region’s industrial competitive advantages between 2012 and 2023 by holding national growth rates constant. This method calculates the rate at which a regional industry is likely to grow over a period of time based on the national growth rate (expected growth), compared to the rate at which it actually grew (actual growth). The difference between actual growth and expected growth represents the industry’s “change due to local shifts,” and illustrates the degree to which inherent characteristics or market conditions within a given region are causing an industry to underperform or overperform the nation as a whole. This measurement of competitiveness is not an indicator of whether an industry is growing or shrinking—rather, it represents what an industry’s growth trajectory would have looked like if it were completely independent from the headwinds and tailwinds of the U.S. economy writ large. All metrics in this shift-share analysis are calculated at the detailed industry level and aggregated by sector to provide a bottom-up accounting of employment shifts for each region.

This report also analyzes economic opportunity in Southeastern Pennsylvania based on its share of “struggling families” and “opportunity jobs.” In this report, “struggling families” are defined as families with incomes that do not cover the typical basic costs of living in the regions where they live, while “opportunity jobs” are defined as jobs that provide health insurance and pay a wage sufficient for covering these costs of living (“good jobs”) or offer strong career pathways into these types of jobs within 10 years (“promising jobs”).

For more information, see the attached technical appendix.

Key terms

|

Growth |

Scale of a regional industry or economy over time (based on employment levels in this market assessment, except where specified otherwise). |

| Prosperity | Distribution of wealth and income produced in an economy on a per-person or per-worker basis. |

| Output | Total value of goods and services produced in a regional economy. Also known as gross domestic product (GDP), gross metropolitan product (GMP), or gross regional product (GRP), depending on the region of reference. All values are changed to 2023 inflation-adjusted dollars. |

| Average annual earnings | Total wages, salaries, and supplements per worker. |

| Productivity | Total output per job. |

| Industry clusters | Industries linked together in a regional economy through shared supply chains, common talent pools, and knowledge spillovers. Industry clusters are typically anchored around tradeable industries, though they can be supported by strong locally serving and public sector entities. |

| Tradeable industries | Industries that participate in national and global supply chains through the trade of goods and services across regional borders (such as most types of manufacturing, finance, consulting, and wholesaling). |

| Locally serving industries | Industries that provide goods and services to consumers within the confines of the regional marketplace where they operate (such as real estate, personal services, construction, and health care). |

| Public sector industries | Governmental and quasi-governmental industries, including state, local, and federal governmental agencies, except for publicly owned institutions of higher education (which are typically considered tradeable) and publicly owned hospitals and secondary schools (which are typically considered locally serving). |

| Competitiveness | A measure of strength in a regional industry sector or cluster based on its growth trajectory relative to the nation. Analyses of competitiveness (called “shift-share”) disaggregate the components of regional industry performance to determine whether its trajectory is a product of locally competitive shifts or a byproduct of national tailwinds. |

| Industry mix effect | The rate of growth a regional industry would have experienced if it had grown at the same pace as the industry nationwide, holding constant the national growth rate writ large. |

| National growth effect | The rate of growth a regional industry would have experienced if it had grown at the same pace as nation writ large. |

| Expected growth | The total anticipated growth rate of a regional industry sector or cluster over time, based on industry mix and national growth effects. |

| Change due to local shifts | Actual realized growth of a regional industry sector or cluster over time, less expected growth (also referred to as “competitive shifts” or “competitive effect”). |

| Specialization | The concentration of regional employment in an industry relative to the concentration of employment in that industry nationwide (also referred to as an industry’s “concentration” or “location quotient”). |

| Cost of living | Total amount required to cover basic necessities (including housing, child care, food, transportation, and health care) based on the number of adults and children in a household, accounting for tax obligations, emergency savings, and retirement contributions. |

| Struggling families | Families with incomes that do not cover their standard costs of living for basic necessities (including housing, food, child care, health care, transportation, tax payments, and emergency and retirement savings). |

| Self-sufficiency | The wage equivalent required to cover the basic costs of living for an individual based on their family structure. |

| Opportunity jobs | Jobs that create opportunities for worker mobility through family-sustaining wages, employer-sponsored health insurance (a proxy for job stability and other benefits), and pathways for upward economic mobility. Opportunity jobs can be considered either “good” or “promising.” |

| Good jobs | Jobs that pay family-sustaining wages and offer employer-sponsored health insurance. The family-sustaining wage rate is $29.76 across Southeastern Pennsylvania for full-time, year-round workers, with some variability by county to account for differences in cost of living. |

| Promising jobs | Jobs that do not qualify as “good jobs,” but create strong pathways into good jobs for workers within 10 years. Promising jobs are particularly critical avenues for economic mobility for workers without a four-year degree, who stand to benefit most from targeted workforce development and upskilling strategies. |

Southeastern Pennsylvania missed out on 188,200 new jobs between 2012 and 2023

Throughout the 19th century, Southeastern Pennsylvania was among one of the strongest manufacturing hubs in the country, leading other fast-growing cities such as New York in the production of chemicals, metals, textiles, and trains. Access to the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers made the region a prime location for fabric, lumber, iron, and steel mills, which relied on those water sources for both power and access to trade routes that connected the economy to other major U.S. and European ports. It is this rich history of innovation, production, and interregional commerce that earned Southeastern Pennsylvania the nickname “the workshop of the world.”

While Southeastern Pennsylvania continues to hold tremendous economic influence and innovative prowess, the sectors driving its regional economy are very different now than they were even three decades ago. Following the emergence of the third industrial revolution in the mid- to late-20th century, Southeastern Pennsylvania—like many other Rust Belt metro areas—significantly deindustrialized. While manufacturing remains a sizable source of employment, with growth in some segments, job creation in the region’s modern economy is anchored around health care services and higher education (“eds and meds”), as well as high-skill and largely white collar industries such as professional and scientific services, finance, and insurance. Between 2012 and 2023, Southeastern Pennsylvania’s health care sector added more than 96,400 jobs (the most of any sector by far, accounting for more than 25% of net job growth), while manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, agriculture, mining, and the public sector saw net job losses.

Though Southeastern Pennsylvania’s job growth over the past decade may appear to suggest that the region is becoming more economically competitive (particularly within its highest-growth sectors), national data indicate otherwise. This is because as Southeastern Pennsylvania has been adding jobs, so too has the national economy writ large. If Southeastern Pennsylvania’s economy had kept pace with national growth between 2012 and 2023, it would have grown its regional employment base by 24%—8 percentage points higher than its actual growth rate of 16%. This reveals significant untapped potential in Southeastern Pennsylvania and demonstrates that the economic conditions at play in the region are running counter to national tailwinds.

This job growth deficit—which amounts to approximately 188,200 missing jobs—has several important implications for the future of Southeastern Pennsylvania’s economy. If the region’s economy is growing more slowly than the nation after controlling for its industry mix, there must be other regions that rely on these industries that are growing faster. Of Southeastern Pennsylvania’s closest regional peers (Boston, Dallas, Atlanta, Detroit, and Phoenix), only Detroit had weaker job growth between 2012 and 2023.19 This indicates that several of the metropolitan economies Southeastern Pennsylvania competes with in the global marketplace are benefitting from social, economic, and political conditions that are enabling them to flourish and grow more than Southeastern Pennsylvania.

Importantly, shift-share analyses do not provide insight into what conditions are fostering growth in other regions yet weakening growth in Southeastern Pennsylvania (e.g., tax competitiveness, housing supply, land use). But such analyses do demonstrate that these conditions exist. And while weakened growth in Southeastern Pennsylvania does not suggest that the region’s major industry sectors are backsliding, it does suggest a gradual loss of market share to other regions, which puts future job growth at risk. Continuing to lag national growth in this way could also have adverse effects on the region’s ability to attract and retain businesses and talent. While most of Southeastern Pennsylvania’s largest industry sectors are growing now, the region’s competitiveness challenges may to lead to increasingly stagnant job growth or even outright decline if left unchecked.

Southeastern Pennsylvania’s growth deficit is most pronounced in its tradeable industries, stalling regional wage growth and productivity

Beyond this high-level assessment of industry competitiveness, measuring the health of Southeastern Pennsylvania’s economy requires an in-depth evaluation of how the region’s tradeable industries are performing. Tradeable industries (those that sell goods and services outside the region) bring new wealth into the economy, which spurs added economic activity and bolsters worker productivity and wages. Though tradeable industries accounted for just one-third of employment in Southeastern Pennsylvania in 2023, they were responsible for 44% of total employee wages and generated more than half of the region’s total economic output. These outsized economic contributions create high returns on investment for workers in these industries, who are 2.5 times more productive and earn nearly twice as much in average annual wages compared to workers in locally serving industries (which primarily sell goods and services in the regions where they operate).20

What counts as ‘tradeable’?

Tradeable industries are industries that participate in national and global supply chains by buying and selling goods beyond the borders of a given regional economy. Conversely, industries that are “locally serving” provide goods and services to consumers within the confines of the region where they operate. Locally serving industries exist in nearly every regional economy, while tradeable industries are more likely to concentrate in regions with many firms operating across their supply chain, creating “industry clusters.” The multiplier effects of tradeable industries on wages and productivity and their ability to provide regions with competitive niches that may not exist in other regions make them much stronger candidates for regional economic development efforts.

It is important to note that industries can fall on a continuum of tradability depending on regional conditions. For example, because of institutions such as the University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Southeastern Pennsylvania’s health care and social services industry (which accounts for approximately 17% of the region’s jobs) is deeply interconnected with the region’s tradeable higher education and professional research sectors. Still, most of the productivity and wage multipliers this connectivity creates are likely to concentrate in tradeable areas of the economy. This report classifies the education sub-sector of colleges and universities as tradeable but the rest of educational services as locally serving, along with all sub-sectors of health care and social services.

For these reasons, Southeastern Pennsylvania’s tradeable industry performance should give the region’s leaders cause for concern. Between 2012 and 2023, locally serving industries such as health care, real estate, and personal services added more than three times more jobs than tradeable industries. Southeastern Pennsylvania added fewer than half of the jobs in tradeable industries than it would have if it had kept pace with the nation—a gap equivalent to more than 104,000 jobs, 70% of which would have been expected to offer opportunity for workers to support themselves and their families.

|

Jobs (2012) |

Expected change |

Actual change |

Change due to local shifts |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tradeable industries |

783,619 |

197,955 |

93,921 |

-104,034 |

|

Locally serving industries |

1,440,427 |

368,248 |

295,896 |

-72,352 |

|

Public sector |

134,986 |

3,945 |

-7,864 |

-11,810 |

|

Total |

2,359,031 |

570,149 |

381,953 |

-188,196 |

This pronounced lag in tradeable industry growth poses significant concerns for not only Southeastern Pennsylvania’s future growth prospects, but also for the well-being of its workforce. Between 2012 and 2023, earnings for workers in tradeable industries were expected to rise along with employment; therefore, as the region’s job growth has lagged the nation, so too have earnings, resulting in real wage growth for these Southeastern Pennsylvania workers nearly 10% lower than expected (an equivalent of $10,867 in missing annual wages per tradeable industry worker). Additionally, because workers in tradeable industries earn significantly higher wages than workers in locally serving counterparts, lagging wage growth in tradeable industries has led to wage stagnation across Southeastern Pennsylvania’s entire economy. The average worker in Southeastern Pennsylvania earned only $460 more per year in 2023 than they did in 2012 after adjusting for inflation—an increase of just over half a percentage point. Workers in the tradeable industries that comprise such a large share of total earnings in Southeastern Pennsylvania earn an average of $70 less per year than they did a decade ago.

Southeastern Pennsylvania’s industry underperformance is eroding pathways for economic mobility

These competitiveness challenges have significant implications for regional economic opportunity. Opportunity jobs—which include both “good jobs” and “promising jobs”—represent the region’s strongest pathways to economic mobility. “Good jobs” are defined as those paying at least $29.76 per hour and providing health insurance. “Promising jobs” don’t yet meet that standard, but offer a clear career pathway into a good job within a decade. Together, these jobs form the bedrock of economic opportunity for the region’s working families.21

Importantly, not all sectors offer the same access to these jobs. Tradeable industries offer opportunity jobs at a nearly 50% higher rate than locally serving industries. This makes Southeastern Pennsylvania’s stagnant growth in tradeable industries especially concerning—not just for the region’s competitiveness, but also for the quality of jobs available to residents.

Access to opportunity jobs is profoundly influenced by access to education and skills. As of 2023, about one-third of the workforce held a good job, while another 19% held a promising job. But access to these jobs is increasingly skewed: More than half of opportunity jobs now require a college degree, even though only 43% of adults in Southeastern Pennsylvania have one. As growth has weakened in traditionally high-opportunity sectors such as manufacturing, workers without a four-year degree have been left with fewer opportunities for upward mobility and pathways into the middle class.

These rising barriers to opportunity job access for workers without a college degree are inextricably linked to changes in Southeastern Pennsylvania’s industrial structure. As Southeastern Pennsylvania’s economy has pivoted toward professional services, health care, and hospitality over the past generation, there have been fewer opportunity jobs available to workers without a college degree. Instead, the skills needs for these sectors increasingly resemble a barbell, with lots of high-skill, expert-level job opportunities and lots of low-wage work in services and maintenance, and few opportunities in between.2223

The consequences of this labor market divide are already being felt by the region’s workers and their families. Nearly 38% of Southeastern Pennsylvania’s population—including more than a quarter of all workers—now live in a family that struggles to cover their basic costs of living (including housing, child care, food, transportation, health care, emergency savings, miscellaneous necessities, and taxes).24 This economic divide disproportionately impacts Black and Latino or Hispanic workers, who have long been underrepresented in occupations that offer the strongest pathways into the middle class.

Charting a new course for Southeastern Pennsylvania will require addressing the region’s competitiveness and economic mobility challenges

At present, Southeastern Pennsylvania’s challenges with competitiveness and opportunity appear to be creating mutually reinforcing economic weaknesses for the region. Lagging growth in tradeable industries and overemphasis on locally serving industries such as health care are contributing to a deficit of the opportunity jobs that the region’s workers need to thrive. Workers who cannot afford to make ends meet in the places where they work, or match to job opportunities that provide them the means to do so, are less productive25 and more likely to look for work elsewhere.26 These factors often directly hinder regional economic growth, as businesses face higher hurdles for attracting and retaining talent.

With coordinated and strategic intervention, however, Southeastern Pennsylvania has the means to invert these mutually reinforcing economic weaknesses into mutually reinforcing economic strengths. By recognizing that sector-agnostic job growth is not in and of itself a sufficient solution to economic mobility and income inequality,27 regional leaders can direct attention and resources toward industries with higher shares of opportunity jobs accessible to a broader range of education levels, while fostering stronger talent pipelines to connect workers in the community to these jobs. The region can further increase its likelihood of success in these strategies by focusing on industries that show emergent competitive strengths, even at a small scale, alongside the larger “anchor” industries that Southeastern Pennsylvania needs to accelerate to preserve its competitive foothold in the national and global economy.

Additionally, each of the region’s five counties must recognize that economic competitiveness and opportunity are neither uniquely city nor uniquely suburban problems. While Southeastern Pennsylvanians living in the suburbs are significantly less likely to struggle to make ends meet than their neighbors in the city of Philadelphia, the latter place contains a higher share of opportunity jobs and has experienced stronger, more competitive job growth since 2012.28 Workers already view the labor market as regional in nature, relying on jobs available throughout Southeastern Pennsylvania for economic opportunity, particularly when they have been unable to match to opportunities in the counties where they live.29 Businesses source their talent and innovation supports and build their value chains irrespective of local governmental lines. Charting a new course for economic growth will require each of Southeastern Pennsylvania’s five counties to be able to tap into the economic and human capital assets available across the regional ecosystem to meaningfully address their shared competitiveness and opportunity challenges.

Advancing regional prosperity by collective action in prioritized opportunity clusters

Despite its challenges, Southeastern Pennsylvania holds substantial economic assets that can support a more competitive and prosperous future if the region acts more collectively and purposefully to fully realize its potential. This means aligning around a shared, evidence-based strategy that narrows from what is doable to what is desired—focusing on sectors showing economic potential and competitive positions that also concentrate creation of quality jobs accessible to a broad range of residents.

Extensive analysis undertaken over late 2024 and early 2025 considered a range of quantitative and qualitative factors to reveal priority clusters for Southeastern Pennsylvania that are both broad enough to have meaningful impact and focused enough to organize for action.30 This analysis included:

- Novel mapping of region-specific industry clusters utilizing firm- and industry-level data sources, including firm descriptions, occupation-to-industry staffing matrices, and input-output models, to enable visibility into emerging specializations beyond traditional industry verticals, which are often obscured by national economic models.

- Consideration of the growth, competitiveness, specialization, scale, opportunity job share, and upward mobility within each cluster, to narrow the set of possibilities.

- Evaluation of the match between cluster talent needs and the region’s workforce and educational offerings, along with presence and performance of relevant innovation ecosystem assets and activities (e.g., university research channels, growth capital, intellectual property, and foreign direct investment). These factors provide additional context for decisionmaking.

- Engagement with companies, intermediaries, and other stakeholders in possible industry categories through interviews, roundtables, and presentations to assess business strategy, gather market intelligence on challenges and opportunities, and confirm sector options.

These qualitative and quantitative factors are in alignment with the Harvard Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness’ Porter’s Diamond Model, a framework for cluster development that posits that many factors (not only existing demand conditions such as scale and specialization) matter in developing a quality business environment where industry clusters can thrive. While these are important preconditions for cluster identification and prioritization, they are often insufficient without robust and supportive supply chains, alignment with existing regional innovation and talent capacity, and strong civic momentum.

Following these considerations, this analysis identified strong opportunities for growth in three of the region’s largest value chains: 1) enterprise digital solutions; 2) materials machining/fabrication and electronic components value chain; and 3) biomedical commercialization. By focusing on these clusters for economic and workforce development intervention, Southeastern Pennsylvania will be well positioned to evolve its legacy assets in finance and insurance, software development, life sciences research, and advanced manufacturing into new clusters that can compete in the global economy.

One rung out from these priority clusters is a myriad of other industries that support them. These secondary “enabling” industries are critical in providing the talent, intermediate materials, infrastructure, and other distribution assets that all three priority clusters need to thrive. While these industries provide many of the same economic benefits as the priority clusters identified above, their presence and strength in Southeastern Pennsylvania is often contingent upon the scale and growth trajectory of the priority clusters themselves.

Prioritizing these clusters for economic development in Southeastern Pennsylvania does not suggest that other industries do not hold economic value for the region. Chester County, for instance, hosts a distinct agriculture industry that is not widely shared across Southeastern Pennsylvania’s full geography; localized strengths such as these are best stewarded by individual jurisdictions versus a regionwide economic development strategy. In the same vein, several locally serving industry sectors such as construction and health care often contain a high volume of opportunity jobs, and should still be considered in workforce-based efforts for connecting workers into economic mobility pathways (for more information on the consideration of locally serving industries in regional economic development strategies, see “What counts as ‘tradeable’?” sidebar above). Regional leaders should acknowledge the important role industries such as these play in job growth and local communities, while also recognizing that they are not the primary focus of the type of shared, regionwide economic development strategies that Southeastern Pennsylvania needs to compete in the modern economy.

Priority sector #1: Enterprise digital solutions

|

Jobs |

Opportunity jobs |

Real gross regional product |

|---|---|---|

|

39,284 (+23.5% from 2012) |

31,044 (57% good, 22% promising) |

$15.6 billion |

Sector definition

Enterprise digital solutions as a priority sector for Southeastern Pennsylvania comprises business-to-business (B2B) cloud-based software tools and platforms, with customization and deployment services, that manage and optimize back-office, middle-office, and customer experience, and are applied across a range of knowledge-based and manufacturing industry segments. Although the region is home to some of the world’s largest and highest-growth enterprise digital solutions companies, the sector has not been generally recognized as a driver of the Southeastern Pennsylvania economy or as defining its technology niche.

Despite lacking a formal vertical industry classification, network analysis of the region’s firms and occupations surfaced enterprise digital solutions as a braiding and blending of activities into a distinctive regional cluster opportunity. It emerges from regional strengths in data processing, computer programming, and Software as a Service (SaaS), connected to a long-standing adjacent industry presence in financial transactions and asset management, clearinghouse activities, and manufacturing.

The region’s enterprise digital solutions firms operate in both general domains such as Business Process as a Service (BPaaS) for automated operations or Integrated Platform as a Service (iPaaS) for data integration and system connections, and specialize within industry verticals such as financial technology, health technology, and governance, risk, and compliance. While a broader definition of “enterprise tech” could encompass B2B information technology activities from storage and networking equipment to managed IT services and hosting, Southeastern Pennsylvania’s position is targeted to the processes and data that power internal operational, administrative, and strategic functions, recognizing historic strengths in regulated industries.

Enterprise digital solutions cluster foundations trace back to the 1980s, when SEI Investments started offering its proprietary internal automated systems as a service to other funds, and the 1990s, when SAP established its North American headquarters in Delaware County to serve regional clients. Subsequent business formation and foreign investment has been drawn to or spun out of the base of enterprise digital solutions users and complementary firms.

The cluster’s name reflects market feedback around the continued digital transformation of business operations through technology, including use of artificial intelligence; the complex requirements and regulatory environments of the firms served; and the characteristics of integrating technical software tools with tailored services to solve bespoke company challenges.

|

Function |

Description |

Representative regional companies |

|---|---|---|

| Enterprise resource planning and operations (ERP) | Core business platforms for finance, human resources, supply chains, customer relationships, compliance. | SAP, Boomi, Vertex, Odessa, Savana |

| Business process management (BPM) | End-to-end optimization of processes and workflow automation, including in manufacturing. | SAP, DXC, Onbe |

| Financial technology (fintech) | Internal financial services operations in investment, banking, payments and processing, risk mitigation, and compliance, including for fund and asset management, insurance, and real estate. | SEI, Citco, Vertex, iPipeline, Equisoft, Envestnet, Simpay, AKUVO |

| Health care operations technology | Platforms tailored for health care administrative processes such as revenue cycle management and patient engagement. | InstaMed, NeuroFlow, Clario |

| Data and analytics | Data management, business intelligence, and visualization tools. | Qlik, Boomi, dbt Labs |

| Digital integration | Systems architecture, platform customization, cloud deployment, and strategy. | EPAM, Chariot Solutions, Relay Network, Odessa, Savana, Bridgenext, Nimbl |

| Middleware and platform enablement | Tools for cloud-native integrations and communication across applications. | Boomi, Relay Network, EPAM |

| AI and intelligent automation | Application of artificial intelligence and machine learning to automate decisionmaking, predictions, and workflows. | Guru, Arcweb Technologies, NeuroFlow, EPAM, Bridgenext |

Market rationale, dynamics, and considerations

Prioritizing enterprise digital solutions for regional economic organizing is supported by market demands, scale of presence and performance, opportunity job concentration, and momentum in innovation. It also has the potential to deliberately amplify clustering effects through talent pipelines, entrepreneurship, and promotion.

The enterprise digital solutions sector supports nearly 39,300 jobs in Southeastern Pennsylvania—a 23.5% increase since 2012. Approximately 40% of these jobs are held by workers without a four-year degree. However, the full extent of enterprise digital solutions-related employment and talent adjacencies may be masked by traditional industry classifications. For example, within financial services, SEI is categorized as an “investment fund,” although a primary line of business is enterprise digital solutions provision to other firms. And technology-driven financial services firms such as Vanguard run internal enterprise technology operations that employ more workers than many enterprise digital solutions companies.

Enterprise digital solutions is also among the region’s strongest catalysts for opportunity job creation. Nearly four in five enterprise digital solutions jobs qualify as good (57.1%) or promising (21.9%). Furthermore, skills that jobs in the cluster require are strongly aligned across levels of educational attainment, particularly between college graduates and workers with some sub-baccalaureate postsecondary education (e.g., vocational credentials or associate degrees).31 Qualitative employer and intermediary feedback regarding recruitment challenges indicates willingness to consider more skills-based hiring, apprenticeship initiatives, and human resource practices that reach a larger pool of workers in communities or demographic groups that are not typically connected to the industry.

Consensus on market potential for enterprise digital solutions is that it is a large and growing industry, albeit challenging to estimate consistently among and within targeted sub-segments. For example, a conservatively defined market valuation of only software in enterprise resource planning; customer relationship, supply chain, and content management; and business intelligence totaled about $108 billion in North America and $263.8 billion worldwide in 2024, with a projected five-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.6% in the U.S. and 12.1% globally.32 Additionally, market analysts and regional intermediaries note that enterprise digital solutions product costs are decreasing, which expands the customer base for adoption by middle-market and smaller firms. A broader set of enterprise digital solutions users, combined with heightened emphasis on creating tailored offerings to specific industries and integration of generative AI, indicates space for further new business creation.

Measures of entrepreneurial activity reinforce this positive direction for business dynamism in enterprise digital solutions. From 2018 to 2023, Southeastern Pennsylvania enterprise digital solutions startups closed 352 venture capital deals. Further, the value of the capital invested in 2023 compared to 2018 rose by $187.4 million—an increase of about 220%, discounting the over 600% spikes during 2021 and 2022, which reflected national post-pandemic trends in overall investment activity.33

The prevalence of foreign direct investment (FDI) in enterprise digital solutions industry categories—with roughly 124 foreign-owned establishments, one-fifth of which are U.S. headquarters—signals recognition of conducive assets and industry ecosystem maturity. Concentrations of FDI tend to draw in more global activity from source countries with the validation of peer firms, plus work in reverse through relationships that establish trade linkages and boost exports; this is reflected in the prominence of regional FDI from India and Southeastern Pennsylvania companies with a complementary presence there, with services not subject to heightened trade barriers for goods. To a lesser degree, Nordic markets also share notable FDI connections. These geographies have not been priorities for the region’s international engagement, and so may warrant a shift in strategic emphasis.

The following observations from exploratory discussions with established and early-stage regional firms, intermediary and innovation groups, investors within and outside the region, and industry observers validate the sector’s potential alongside opportunities to accelerate growth and inclusion:

- Even without full awareness and organizing reflective of the region’s enterprise digital solutions prominence, the sector has grown organically and dramatically.

- Larger enterprise digital solutions employers identified continuing job growth accompanied by increased difficulty in workforce recruitment in the region across all levels of credentialing, forcing them to consider shifting jobs to U.S. or international outposts in regions with more structured talent pipelines. Some attributed challenges to a tighter labor market, lack of B2B firm brand visibility among workers in the region compared to competing tech hubs, and market failures in information among employers and talent providers that suggested the potential for an intermediary to facilitate an industry partnership for talent pipeline management.

- The advancement of artificial intelligence may impact the availability of technical and management occupations in enterprise digital solutions, but not necessarily in a negative way. Industry experts foresee potentially greater disruptions among computer science and software engineering positions with four-year degrees than in client solutions development and services or opportunity jobs with reduced degree expectations. Further, AI software companies represented about 50% of enterprise tech venture capital deals completed in the metropolitan area in 2024, indicating business dynamism and new growth in the sector.34

- Some investor groups report that regional enterprise digital solutions companies in their portfolios have been more consistent performers with above-average success rates.

- Specialized enterprise digital solutions supports dedicated to B2B SaaS startups in the region continue to emerge, such as venture studios, advisory groups, and capital sources—complementing prior connections by enterprise digital solutions firms to assets such as the Drexel Solutions Institute and Comcast LIFT Labs.

Overall, informants observed that regional economic and workforce efforts tend to promote general “tech economy” or “information technology” talent initiatives, rather than organizing explicitly around the enterprise digital solutions segment’s distinctive characteristics and needs. At a smaller scale, organizations with enterprise digital solutions-related firm and investor relationships such as the Philadelphia Alliance for Capital and Technologies (PACT) emphasize the sector by holding an annual enterprise tech forum and piloting a registered apprenticeship for some enterprise digital solutions employers, alongside more universal tech business networking, capital availability, and mentorship programs. However, feedback highlighted the industry perception that enterprise digital solutions is not given mainstream economic and workforce development attention, and investment is required to ensure the region provides conditions for continued success.

Priority sector #2: Materials machining/fabrication and electronic components value chain

|

Jobs |

Opportunity jobs |

Real gross regional product |

|---|---|---|

|

25,772 (+3% from 2012) |

14,944 (38% good, 20% promising) |

$6.6 billion |

Sector definition

The region’s materials machining/fabrication and electronic components value chain strengths encompass production in precision metalworking and polymer processing, industrial and process equipment, high-tolerance electronic connectors and instrumentation, communications systems and control devices, and related assemblies. Target manufacturing capabilities center on a value chain built off precision engineering, machining, and component integration processes.

While some representative firms include headquarters or subsidiary outposts of larger, global companies such as TE Connectivity, AMETEK, Nicomatic, and Teledyne Judson Technologies, the vast majority of these firms are small and medium-sized businesses (and often family-owned) such as R-V Industries, Rhoads Industries, and CCC Engineering and Contract Manufacturing. This value chain also is supported through some intraregional anchors, such as helicopter assembly by Boeing and Leonardo or shipbuilding by Hanwha Philly Shipyard.

However, rather than reliance on a localized customer base or an industry vertical such as defense or aerospace, these firms significantly export outside Southeastern Pennsylvania across a range of customers. This represents more of a comparative advantage based on capabilities rather than supply chains, where the commonalities shared for opportunity job creation and competitiveness are in occupational needs, manufacturing processes, capital-intensive equipment, and infrastructure.

Market rationale, dynamics, and considerations

Southeastern Pennsylvania retains cross-cutting competencies and a substantial position in these segments of value-added advanced manufacturing, with overall growth in opportunity jobs even as larger-scale job creation has shifted to the U.S. South and Midwest or international locations. Manufacturers in materials fabrication and electronic components named regional advantages associated with legacy industry operations, the workforce, proximity to markets, utilities, and logistics capabilities.

These manufacturing sub-sectors employ roughly 25,800 workers across the region. Overall job growth was net positive over a decade, although relatively modest at 3%; that average was tempered by significant job losses at large-employer aircraft manufacturers such as Boeing in the late-2010s. In contrast, several specialized but smaller categories such as architectural metalworking, precision gear and transmission manufacturing, and communication equipment have notably outperformed their benchmarks for expected job creation.

The sector also concentrates accessible, quality jobs. About 58% of positions are opportunity jobs, with two-thirds of those meeting the “good job” standard. Jobs for mid-skill workers holding less than a bachelor’s degree account for 67% of the sector.

Qualitative engagement with small and midsized manufacturers in the target sub-sectors consistently reinforced potential for further growth. A diverse set of firms throughout the region reported having unmet demand for their products and business plans for expansion that they could not fulfill, principally attributed to workforce availability. As a result, some locally headquartered middle-market firms are exploring acquisitions outside the region and state as an alternative to satisfy demand. Similarly, several subsidiary firms (including foreign-owned and multinational corporations) have sought to establish or scale up their presence in other U.S. markets, rather than expand their operations in Southeastern Pennsylvania. Because the talent pipeline does not meet the needs of growing companies in Southeastern Pennsylvania, the region is losing out on new, high-quality manufacturing jobs it would otherwise be getting.

Analysis of research and development (R&D) activity and capital flows also supports the ongoing broader possibilities in the materials fabrication value chain. The region’s concentration of university R&D activity focused on materials sciences doubled between 2016 and 2023. Although patenting is dominated by life sciences and health care, the region also shows modest strengths in relevant elements of chemistry and metallurgy, such as coating compositions and adhesives or adhesive processes.

Despite these core strengths and potential, manufacturing sub-sectors have not been a primary emphasis for regional economic or workforce development strategies and investment at a level commensurate with the opportunity. Qualitative input indicated that training and financing programs are not sufficiently scaled, visible, or targeted to fulfill employer needs. Firms, commercial bankers, private equity investors, and merger and acquisition advisors validated the sub-sector’s potential if enabling ecosystem factors were to be addressed.

The dominant role of workforce issues in accessing untapped potential reflects the region’s overall underemphasis on the talent pipeline, alongside localized talent gaps in certain suburban counties that are attributable to higher housing costs and transportation barriers for the technical workforce. While expertise in mechanical and electrical engineering is needed to fill job openings across the cluster, gaps are particularly acute for foundational, hands-on workers with specialized skillsets, apprenticeships, or postsecondary certifications, but not necessarily a four-year degree. Such positions are seen across computer numerical control machining and programming, tool and die making, welding and fitting, materials handling and finishing, industrial mechanics and maintenance, assembly, and quality control. The ability to meet these occupational needs also spurs accessible jobs in other aspects of business operations such as project management, sales, and accounting.

However, employers also identified examples of existing talent pipeline activities that, if scaled, could address those concerns. Opportunities include significant investments to expand the output of high-quality industry and trades training programs, in which participants are hired well before graduation. In a few instances, upper-middle-market firms initiated and funded their own programs to meet needs, although without achieving the full potential benefits and economies of broader collaboration across employers and training providers. These factors connect to potential in greater financial and technical support for apprenticeships and on-the-job training, plus visibility of manufacturing job demand and greater K-12 exposure and engagement with non-traditional worker populations, building off adjacent efforts by construction trades for similar demographics.

Thus, analysis suggests that the sub-sectors could be significantly advanced through prioritized efforts with workforce providers to fill gaps in market knowledge, ease navigation for smaller firms and potential employees, and increase resources dedicated toward relevant manufacturing occupations.

In considering prioritization, additional assessment identified ways to further unlock long-term growth potential:

- Industrial land uses: Availability and affordability of industrial facilities, especially in more densely developed urban parts of the region, present an increasing constraint. While emphasis is on footprints for small and middle-market firm operations versus mega-sites, this space is in competition with rapid expansion of consumer-oriented warehouse and logistics uses, as well policies to promote housing development. Especially for smaller firms, leasing expenses and hyperlocal zoning and development approvals are constraints to expansion that policy interventions and incentives need to balance.

- Operating improvements: Equipment enhancements, technology adoption, and product refinement technical assistance are common challenges for small and midsized manufacturers, similar to many other U.S. regions and with similar potential for successful responses. As part of acquisitions, private equity investors identified competitive efficiencies by injecting investments in machinery, facility, and process changes that stabilized or grew opportunity jobs. Commercial bankers reinforced potential in expanded capital investment and greater access to technical assistance, such as that provided by the Delaware Valley Industrial Resource Center.

- Succession planning: Given the significant number of family-owned firms in the region and operators nearing retirement with a maintenance versus growth orientation, firms, bankers, and merger and acquisition advisors noted potential proactive succession planning outreach to preserve and boost sector viability.

Finally, the current effectiveness and efficiencies in organizing support for manufacturing priorities are constrained by scale and fragmentation. For example, at least four distinct “manufacturing alliances” serve the five-county region with some overlapping geographic coverage; three are sponsored by separate small “industry partnership grants” from the Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry, complemented by support from sub-regional workforce development boards and local economic development organizations. While these alliances’ leads communicate with each other and share objectives (with an emphasis on workforce issues), their individual staffing and program budget levels cannot match demand and could be aided by more collective approaches.

Priority sector #3: Biomedical commercialization

|

Jobs |

Opportunity jobs |

Real gross regional product |

|---|---|---|

|

50,198 (+27.5% from 2012) |

37,453 (55% good, 20% promising) |

$22.1 billion |

Sector definition

Specific to Southeastern Pennsylvania, biomedical commercialization as a priority cluster refers to slightly broadening and balancing the ongoing life sciences focus for economic and workforce development toward capturing a greater share of mainstream production activities, alongside the more dominant emphasis on promoting discovery activities and emerging platform technologies with longer-term potential for job creation. It also entails addressing the oft-cited challenge of generally retaining more discovery- and seed-stage firms into early and growth stages.

The region’s recognition and organizing around life sciences as an economic development engine is well established. Over the past 20 years, many special initiatives and intermediaries have emerged to promote global visibility, research and development, entrepreneurship, investment, and workforce development.

To distinguish its competitive position, the region placed greatest focus on cutting-edge areas such as cellular biology. This was reflected in interventions from local training to its regional branding of “Cellicon Valley,” still regularly referenced by site selectors.35 Those efforts supported major regional growth evinced in research-related jobs and seed investments.

However, in successfully establishing this new and distinctive market position, the region put less emphasis on traditional strengths in other long-standing and prominent life sciences sub-sectors with more near-term job creation. These opportunities center on manufacturing in specific segments of diagnostics and therapeutics and medical devices, where Southeastern Pennsylvania and the broader metro area already are national leaders.

Opportunities in therapeutics and diagnostics manufacturing are being accelerated by aggressive global supply chain shifts toward more domestic production, as well as growth in newer categories such as biologics, where regions have not yet consolidated competitive positions. These products encompass multiple categories:

- Biologics such as vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, hormones, and blood components

- Pharmaceuticals compounds

- Diagnostics (such as reagents or immunoassays used in testing lab processes)

Southeastern Pennsylvania also has opportunities to expand its medical device sector thanks to the region’s innovation heritage and current manufacturing base. This includes regional prominence in cardiovascular, orthopedic, ophthalmic, diagnostic and imaging, and surgical and critical care devices. Already ranked in the top 10 U.S. medical device manufacturing hubs, the region can aim to capture greater market share by producing what is being invented and tested in the metro area, Pennsylvania, and the Mid-Atlantic, as well as drawing expansions and commercialization from other domestic and international sources. To be successful, the region does not need to fully match its most prominent competitors such as Minneapolis-Saint Paul and Orange County, Calif; boosting current outcomes by a moderate amount can yield significant middle-skill, middle-income job creation accessible to regional workers.

Market rationale, dynamics, and considerations

Southeastern Pennsylvania already is a globally recognized center of research and production in life sciences, which also is the primary tradeable sector around which regional and local economic development has been organized and resourced. The sector has been a major driver of investment and growth in the region. Numerous interest groups, strategies, and local assets—including the Science Center, Pennsylvania Biotechnology Center, Life Sciences PA, and Keystone LifeSci Collaborative—have been dedicated to advance it, from creating incubators, accelerators, and innovation districts to starting specialized technical assistance and financing programs.

As of 2023, the targeted sub-sectors comprised nearly 50,200 jobs in Southeastern Pennsylvania, many of which are housed at highly innovative multinational corporations such as Janssen Biotech, Siemens, DePuy Synthes, Globus Medical, and GlaxoSmithKline. Of the roughly 10,800 net new jobs the region has added in the biomedical commercialization cluster between 2012 and 2023, nearly 9,800 (90%) were attributable to growth in research and development activities, particularly high-skill scientific occupations such as medical scientists and chemists.36 However, despite this level of economic activity, Southeastern Pennsylvania’s growth trajectory has lagged competitors such as Boston, Houston, Raleigh-Durham, N.C., and the San Francisco Bay Area. Further, over the same period, the region has underleveraged its potential for life sciences manufacturing compared to peer markets where innovation and manufacturing strengths are more deliberately interlinked.

Currently, nearly 37,500 jobs in the cluster meet the region’s “opportunity job” criteria, with 55% considered “good” and another 20% “promising.” Within that subset, about 35% of opportunity jobs are accessible to workers without a college degree; while this is still above average, efforts may evaluate whether four-year degree requirements are imposed by practice or necessity to do the work.

The region’s powerhouse life sciences and biotechnology innovation ecosystem undergirds opportunities for biomedical commercialization. Since 2012, the regional industry has produced more than 3,200 patents and attracted over $5.5 billion in growth and startup capital.37 Foreign direct investment trends reinforce the potential of expanding life sciences manufacturing: Biopharmaceutical manufacturing firms lead the region’s traded industries in the number of foreign-owned headquarters and subsidiary locations. This indicates global confidence in the region’s industrial base and suggests potential to leverage FDI relationships for further growth through a deliberate focus.

Since 2019, regional business attraction, retention, and expansion efforts have specifically featured cell and gene therapy as an emerging sub-sector in which Southeastern Pennsylvania holds a strong competitive position compared to peer life sciences hubs. Bringing together about a dozen partner organizations on a shared strategy for business, workforce, and infrastructure development has been the region’s primary example of a joint long-term, large-scale sector initiative, with success in achieving visibility and capturing activity. Nevertheless, the market size and scalability of highly complex, customized cell and gene therapy technologies are challenges to significant near-term job creation. The industry also faces steep regulatory approval and supply chain barriers, particularly in an increasingly difficult funding environment.

At the same time, important challenges will need to be addressed to realize opportunities in expanded focus areas. Over the first half of 2025, firms including Eli Lilly and Company,38 Merck,39 and Amgen40 have announced overall plans or specific locations for investing billions of dollars toward new life sciences manufacturing facilities in the United States. However, Southeastern Pennsylvania has sometimes struggled to compete for location decisions given firms’ established presence in other regions, land availability, better incentive and tax packages from other states, and similar factors. Southeastern Pennsylvania may be most competitive in cases where proximity to its strong R&D and innovation functions can be leveraged to inform or contribute to production processes.

Within medical device manufacturing, some firms have struggled to find contract manufacturers to move from development and pilot to full-scale production in Southeastern Pennsylvania relative to other hubs. Industry contacts also suggest the need for greater information-sharing and facilitation to identify and access the supply chain. Other barriers include capital (a challenge throughout the regional sector) and gaps in medical-device-specific ecosystem supports. As in other sectors, talent pipelines are also a pressure point, although promising workforce development models currently in operation could be scaled to link more employers and workers without a four-year degree from disconnected neighborhoods.

Obstacles to retaining early-stage and growth-stage firms are a long-standing concern in the region, though not currently matched by the level of staff, activity, or funding to overcome them. Working collectively may help make progress on solutions to improve visibility and access to distributed supports across the ecosystem, close capital gaps relative to other life sciences hubs, and expand technical assistance in areas such as CEO skills and management support to help inventors transition to entrepreneurs.

Alignment with Pennsylvania’s economic development strategic plan

This section evaluates the region’s sector opportunities presented above against the five priority industry categories identified in the commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s statewide 10-year economic strategy released in 2024: agriculture, energy, life sciences, manufacturing, and robotics and technology. Aligning with these sector priorities is important for Southeastern Pennsylvania’s ability to secure investments, program support, and policy actions that depend on the state’s scale and governing authority. However, as the strategy acknowledges, the commonwealth’s distinct economic areas—including Southeastern Pennsylvania—boast different assets and strengths, reflecting variable population sizes, industry mixes, and other influences.

Assessment of the region’s industries and cluster priorities against the commonwealth’s economic strategy identified strong yet incomplete connections within the state-defined categories of manufacturing, robotics and technology, and life sciences. It separately reconsidered the region’s position in agriculture and energy as state interests, reaffirming not to prioritize those opportunities for Southeastern Pennsylvania.

- Enterprise digital solutions: Medium alignment. The state plan emphasizes technology hardware manufacturing and highlights semiconductor supply chains, navigational instruments, and electrical equipment more than the kinds of software platforms, data services, and integrated technologies that undergird Southeastern Pennsylvania’s enterprise digital solutions opportunity. This specialization could align in part with the commonwealth’s robotics and technology industry category, which references a competitive strength in autonomous systems that might encompass the software engineering and systems that make physical systems work.

- Materials machining/fabrication and electronic components value chain: Strong alignment. Southeastern Pennsylvania priorities in this sector are consistent with the state’s broad focus on manufacturing and specific prioritization of metallurgy, metals, and plastics (within manufacturing), electronic components such as connectors and sensors feeding various industry supply chains (within robotics and technology), and promoting innovation to enable efficiencies in small and midsized manufacturing firms.

- Biomedical commercialization: Strong alignment. The state plan highlights life sciences research and development strengths alongside boosting commercialization with technical assistance and early-stage capital supports for entrepreneurs. There is lighter emphasis on pharmaceutical and medical equipment manufacturing. Southeastern Pennsylvania’s biomedical sub-sector opportunity relates closely to the commonwealth’s vision for life sciences, but with enhanced emphasis on the nearer-term mid-skill job creation potential of retaining scale-up firms through market delivery and attracting reshored supply chains in manufacturing therapeutics and medical devices.