“We have disadvantaged families and individuals in Singapore, but we don’t have a single disadvantaged neighborhood.” This was one of the most striking statements from Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister, speaking here at Brookings earlier this week at an event on Housing, inclusion, and social equity (video available online).

Singapore has little choice but to manage its housing market closely: it has a population of 5.5 million people on an island of just 278 square miles, the equivalent of the entire population of Denmark living in a city the size of Lexington, Kentucky. But as a nation born by accident and populated by immigrants, Singapore has taken the additional step of effectively forcing geographical integration. There are, for example, legal caps on the proportion of people from a particular ethnic group who can live in a particular neighborhood, or even apartment block.

“This is intrusive,” admitted Shanmugaratnam. Some people, he conceded, would describe this kind of policy as social engineering. They would indeed. But his point was that policymakers end up as social engineers whether they like it or not. The question is simply whether they do their work “upstream,” by preventing segregation and concentrated poverty, or “downstream,” using policy to try and deal with the consequences of segregation. This was a lesson not lost on the Americans in the audience. It was perhaps the most thoughtful argument for progressive paternalism I have heard.

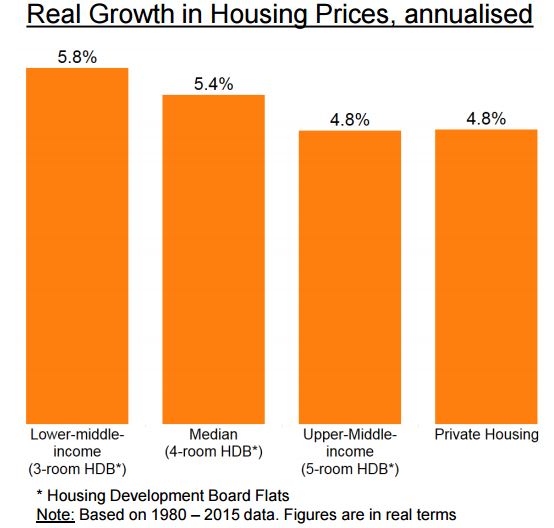

The Deputy Prime Minister insisted that social policy should not simply be seen as a “residual” of economic policy, something we pay for once we’ve secured growth, but as an important element in creating economic stability and success. For example, one result of Singapore’s strict neighborhood integration policies has been to ensure that home values increase across the board, which keeps wealth inequality in check:

To say that the U.S. is in a different situation would be an understatement. While Singaporean public policy has acted specifically to prevent segregation, American policy has mostly done exactly the opposite, through racist laws, practices and attitudes. As Margery Turner of the Urban Institute put it, we have “social engineered ourselves into the current situation.”

There was plenty more on the agenda at the event (a joint effort between Brookings and the National University of Singapore, Duke University and Washington University in St. Louis) including interventions in Panel 1 from Delaware Governor Jack Markell and Newton, Massachusetts Mayor Setti Warren, as well as a galaxy of scholars from Singapore, India, the United Kingdom, and the United States. For a good overview of the U.S. situation see Molly Metzger’s presentation in Panel 2, and her slides here.

One big takeaway: while Singaporean social interventionism is not on the cards, it is clear that U.S. policy makers will have to be much, much more intentional about integration.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Social policy, Singapore style: Lessons for the U.S.

December 2, 2015