China has sought to overwhelm the world’s doubts over its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic with a viral load of positive messaging, positioning itself as a benevolent global saviour. Chinese diplomats and state media, capitalizing on each and every shortcoming of the West, have congratulated themselves on the superiority of China’s political system, which they say enabled the country to respond quickly and decisively.

In truth, it was precisely this insistence on perception over fact, so core to China’s political system, that caused fatal delays in dealing with the epidemic in the key early weeks—and it has continued to drive the manipulation and misrepresentation of essential facts, from the real number of dead to the origins of the epidemic. The Chinese Communist Party’s legitimacy at home and public diplomacy abroad depend desperately on maintaining the integrity of this wall of silence and untruth.

But that wall is being creatively challenged inside China. Dissident voices are insisting on being heard at great personal risk, independent-minded journalists are doing their utmost to push the bounds of coverage, and millions of Chinese are refusing to allow the party-state’s self-serving narrative to go unchallenged. With censors cracking down on reports critical of their handling of the crisis, Chinese online users are getting creative in finding ways to bypass information controls: using old-school telegraph codes for Chinese characters to encode articles and turning to emoticons to skirt censorship.

The party has faced wave upon wave of online anger this year over the folly and insensitivity of its positive messaging in the face of a real and painful crisis. When state media announced, scarcely a month after Xi Jinping’s belated public acknowledgement of the epidemic on Jan. 20, that the Central Propaganda Department had published a new book in six languages to praise China’s response and to “collectively reflect General Secretary Xi Jinping’s . . . . far-reaching strategic vision and outstanding command as the leader of a major power,” the fury burned white-hot online. “There is no vaccine and no cure, but here we have a book,” one user wrote with biting irony. Within a week, the book had quietly disappeared, and all promotion had ceased.

Soon after, on March 5, Vice-Premier Sun Chunlan made a high-profile visit to Wuhan, coming ahead of a planned visit by Xi Jinping. During Sun’s tour of a residential neighborhood, video was captured of residents shouting from their windows: “Fake! Fake! Everything is fake!” The footage, shared across social media, was quickly deleted, re-posted, and deleted again in a war of online attrition against dissenting facts.

The embarrassing episode prompted the party’s new top man in Wuhan, Wang Zhonglin, to remark the next day on the need to “carry out gratitude education among the citizens of the whole city,” so that they might appreciate the efforts of Xi Jinping and the party. Many Chinese, commenting on social media, were apoplectic. Within 24 hours, national propaganda authorities found it necessary to schedule an emergency video conference on “the ‘gratitude education’ incident.” An internal notice on the meeting called it “a classic case of public opinion created by our own work.”

How Chinese have managed to make themselves heard, even in the face of the world’s most robust system of information controls and public opinion manipulation, is a complicated question. But the simplest explanation has to do with connectivity and ingenuity. Like the samizdat of the Soviet era, those “smudged onionskin sheets” that proliferated through the sharing of carbon copies, Chinese posts are shared through friend networks and public accounts on platforms like WeChat. Often, they disappear in a matter of seconds, minutes or hours—only to resurface, altered and disguised, for another round of fleeting attention.

Xi Jinping’s visit to Wuhan on March 10 offered one of the most illustrative examples of this sort of digital rebellion against the all-consuming party narrative. As Xi toured the city, online censors were on full alert. One complicating factor that day was a feature story appearing in the latest edition of China’s People magazine. Based on an interview with Ai Fen, the director of an emergency department at a local Wuhan hospital, the story revealed that she had been the earliest to share a diagnostic report in late December for a patient suffering from what would later become known as COVID-19. The diagnostic report shared by Ai had resulted in harsh police reprimands for eight doctors, including Ai’s colleague Li Wenliang, who had later died of the disease. Ai, who had been called in by her hospital’s disciplinary office and accused of “manufacturing rumors,” expressed her deep regret to the magazine for not having spoken up more forcefully at the time.

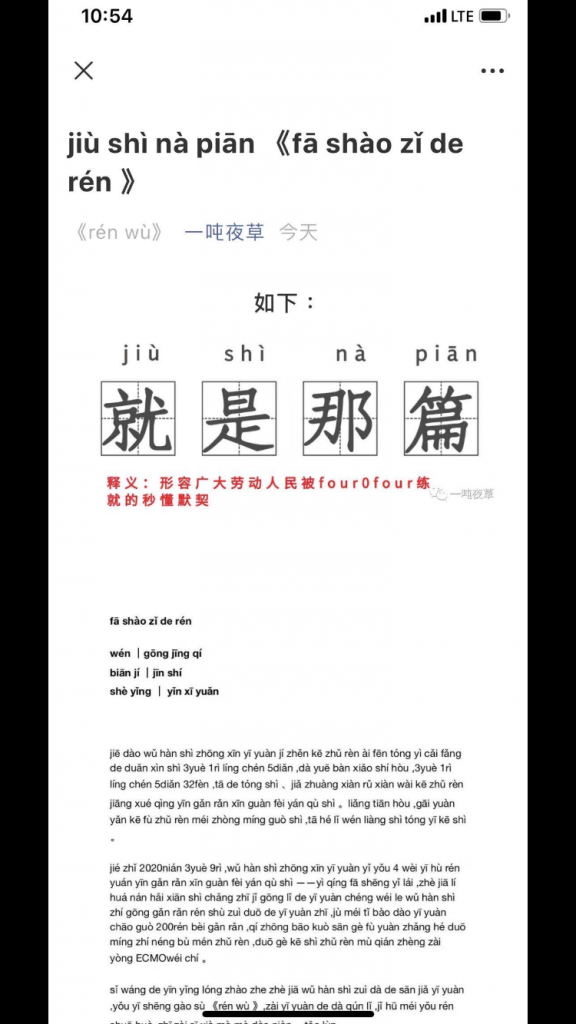

The Ai Fen story was swiftly expunged from the internet and social media sites. Defiantly, it returned. In one version, the entire text was rendered not in Chinese characters, easily recognized by automated controls, but in Romanised form, given a new headline: “This is that article.”

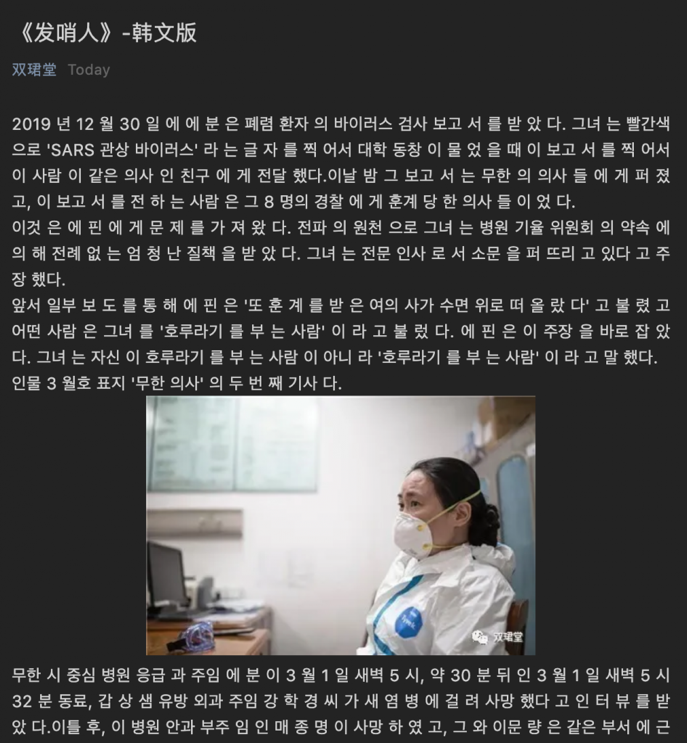

Workarounds proliferated, enabling access, even if again temporary, to the Ai Fen report. But before long, the medium of creative defiance had become its own message. The article, for example, was shared in Korean, which could be auto-translated back into Chinese without difficulty.

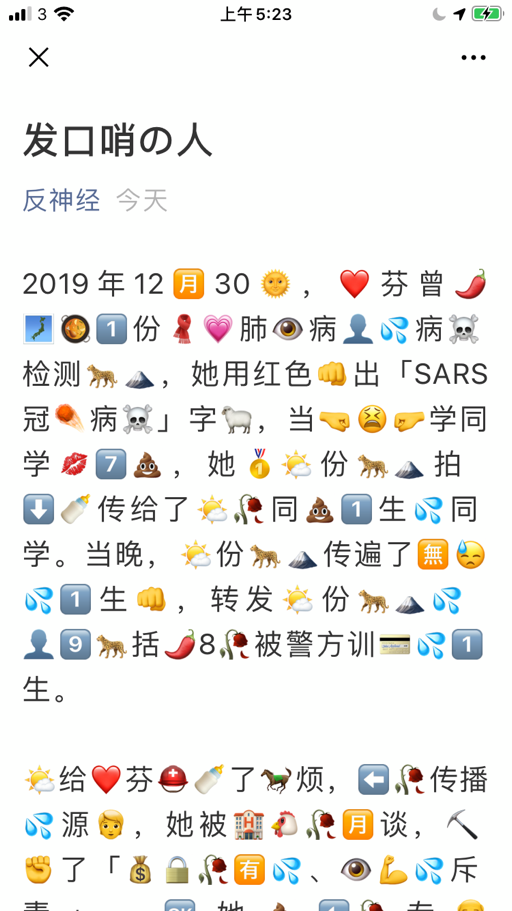

Another clever user rendered the whole report in Chinese characters interspersed and replaced with emoticons, still readable but not easily recognizable. Cute, irreverent, and audacious.

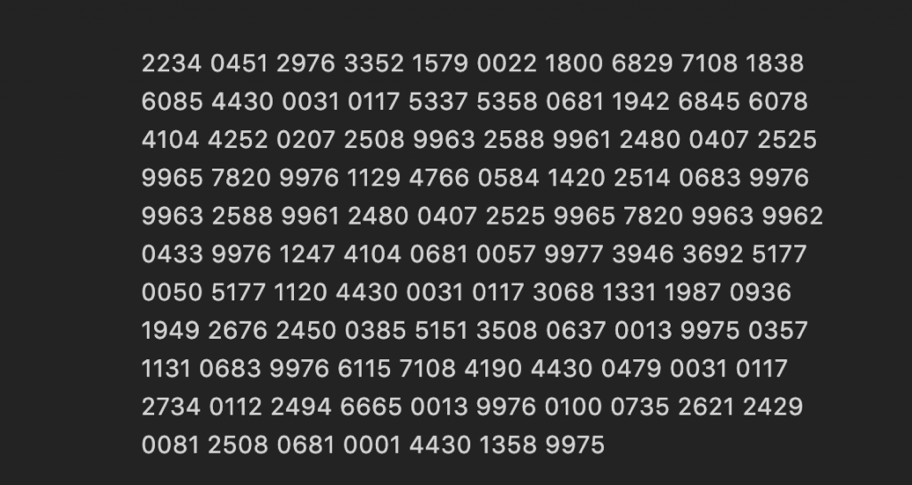

Another solution, one of the most creative and historically literate, employed the four-digit telegraph codes once used to correspond to Chinese characters, allowing the entire Ai Fen report to be decrypted.

The possibilities were virtually endless, and for a time during Xi’s visit to Wuhan, they proliferated through chat groups, all at once making a mockery of controls on speech and providing an exemplary view, through Ai’s words, of why speaking out is a matter of life and death.

As a form of dissent, these digital samizdat are vulnerable and impermanent. But the message they ultimately leave behind is indelible: the silhouette of a system that militates against speech and information in an effort to shape a single voice.

David Bandurski is the co-director of the China Media Project, a research program in partnership with the Journalism & Media Studies Center at the University of Hong Kong.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Skirting Chinese censorship with emoticons and telegraph codes

April 28, 2020