In March 2018, Russian President Vladimir Putin will likely be running in the country’s next presidential election. Putin has been in power for 16 years, and by March of 2018, he will have become the second-longest serving head of state in post-imperial Russian history, after Joseph Stalin and ahead of Leonid Brezhnev. Although the 2018 elections will certainly not be entirely free or fair, for Putin, they will be of great importance as a national referendum on the popularity of his policies.

Ominous signs for the economy

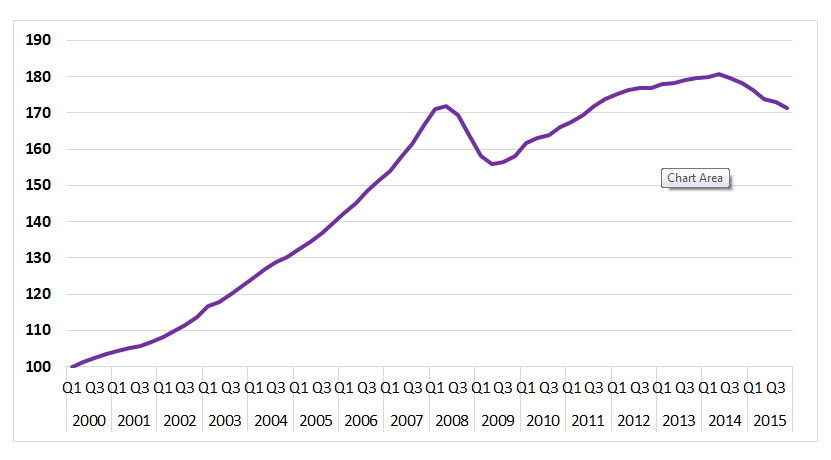

In all three of the past elections in which Putin has appeared on the ballot, the Russian economy was in good shape. In 2000, the economy had recovered from the crisis of 1998 and had embarked on a 10-year period of 7 percent average growth; his second election in 2004 came at the midpoint of that decade. By the third election 2012, the Russian economy had overcome the consequences of the global financial crisis and, it seemed, was returning to a path of sustainable growth—the GDP growth rate amounted to 4.3 percent in 2011.

This time is different. The Russian economy started to slide in the second-half of 2014. Despite some signs of stabilization at the beginning of last autumn, it turned out that they were related to occasional factors—namely, a good harvest, an increase in gas purchases by European consumers, and the end of the production cycle of armaments.

Although the overall level of the decline in GDP was relatively small (3.7 percent) compared with the crisis of 2008, when the drop exceeded 11 percent, the qualitative state of the economy is much worse than it was six years ago. Then, Russia’s economic woes were driven by high volumes of short-term external debt to be repaid, huge foreign exchange risks on the balance sheets of Russian banks, and a sharp fall in demand for the Russian raw materials that accounted for more than 80 percent of total exports. But as global financial markets and the demand for raw materials recovered in the spring of 2009, the Russian economy returned to growth.

Figure 1. Russian GDP Growth, 2000-2015 (Q1-2000 = 100)

Source: Rosstat. Starting in 2014, Crimean data is included.

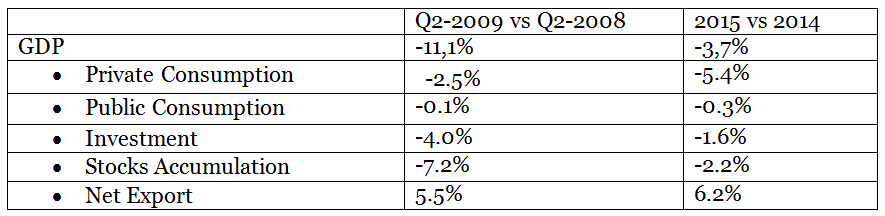

While the current decline in oil prices is proving to be deeper and longer-lasting than six years ago, the demand for Russian raw materials has remained steady. Moreover, exports in physical terms—the production and export of oil, refineries, and coal—increased in the past year. But these trends mask far deeper problems facing the economy. Although preliminary estimates from Rosstat, Russia’s federal statistics agency, may still change dramatically, the main qualitative differences from the last crisis are clearly visible in the table below.

Table

1:

Effect

s

of

g

rowth

and the d

ecline of

c

ertain

d

emand Comp

o

nents

on

o

verall GDP

d

ynamics in Russia

Source: Rosstat.

Two statistics stand out here. First, private consumption fell by 10 percent in 2015, in large part due to high inflation, public sector wages freezes, and the extremely low growth of nominal wages in the private sector. Second, the relatively small fall in investment in 2015 (minus 7.4 percent, as oppose to minus 19.4 percent in the 2008-2009 crisis) would, on its face, appear to be a positive. But it is worth noting that a decline in housing construction only began in June, while in 2015 Russian oil companies completed a massive round of investments in refineries to meet elevated environmental requirements. So, for the first nine months of 2015, the volume of installed capacity in refining totaled 10.8 million tonnes (compared to 5.5 million tons in 2014). So the relatively small drop in investment can be misleading, and this year’s drop may be deeper due to a higher base.

Further declines in oil prices in late 2015 and early 2016 severely worsened the prospects for the Russian economy; few experts are predicting growth if oil prices remain below $40 per barrel. The main victim of the fall in oil revenues is the federal budget, which stands set to lose 8 to 10 percent of its tax revenues for the year. In the last two years, the Kremlin has restricted budgetary planning to three years, the Ministry of Finance has sought annual reductions of 10 percent in expenditure, and wage growth in the budgetary sector and social payments have been virtually frozen, causing them to rapidly depreciate in the face of high inflation.

No good options

In such a situation, policymakers have several options, none of which is optimal. They can hardly raise taxes, as Russian law prohibits doing so in the middle of the year and President Putin has promised not to raise taxes until 2018. They could further cut spending, but this will reduce aggregate demand in the economy and strengthen the recession. They could increase the budget deficit and draw on reserve funds, but this risks depleting reserves quickly and losing the economy’s safety net of last resort. They could pursue a program of privatization for national industries, selling off small portions of state-owned companies and banks. But today’s prices are very low, as is the attractiveness of these assets. Or they could print more money to finance the budget deficit, but this will inevitably lead to higher inflation and a further decline in living standards.

The challenges facing the Russian economy do not presage economic collapse in Russia. The stability of the Russian economy is based on three pillars: stable demand for raw materials in the global economy; market prices that maintain the economic equilibrium; and prudent macroeconomic policies that limit inflation. But these pillars alone do not stimulate growth and cannot prevent economic stagnation.

Difficult choices lie ahead

This lack of economic growth will very soon leave President Putin with a difficult choice.

For a long time, Russian voters have been willing to endure trying economic conditions and reductions in living standards in return for proof that Russia has again become a global power. But patience is wearing thin. The public mood at the beginning of 2016 has changed dramatically, and approval ratings for the government have plummeted. Continued economic crisis and a further decline in living standards, both of which appear to be inevitabilities this year, will erode the electoral coalition that underpins Putin’s dominance of Russian politics—pensioners, civil servants, military personnel, state-controlled businesses, export-oriented industries, and arms manufacturers.

Later this year, when budget planning for 2017 is considered, the Russian president will have to decide what platform he wants to pursue to go into the elections in March 2018. Will he ignore the drop in support and maintain strict budget constraints, or will he abandon budgetary discipline and entice voters by raising salaries and pensions? The first scenario is fraught with danger for Putin. Ordinarily, political opposition in Russia poses no threat to Putin. Declining living standards, however, may spur genuine opposition to his rule which, in turn, might lead to a Kremlin crackdown on what it perceives as a threat to the status quo. Meanwhile, the second scenario may lead to an inflationary spiral and the loss of macroeconomic stability in the country.

We do not know what path Putin will choose, but we do know that the Russian economy will put him at the front of the fork in the road very soon.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Should Vladimir Putin be concerned about the Russian economy?

February 9, 2016