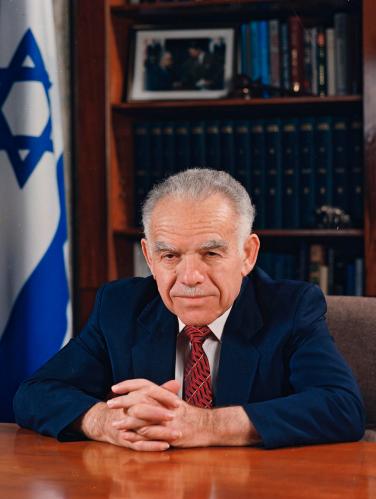

Shimon Peres, Israel’s ninth president, former prime minister and Nobel peace prize laureate, died last night at the age of 93. A mere highlight list of his public positions speaks volumes about his role in Israeli history: president (2007-2014), prime minister (twice, 1984-1986, and, following the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, 1995-1996), minister of defense (1974-1977 and 1995-1996), foreign minister (1986-1988, 1992-1995, and 2001-2002), finance minister (1988-1990), and leader of the opposition (1977-1984, 1990-1992).

Already at the age of 24—before the state was even declared in 1948—he was an aide to Israel’s founding prime minister, David Ben Gurion, and by 30 he was director general of the powerful ministry of defense. First elected to the Israeli Knesset in 1959 and first appointed to the cabinet in 1969, he also held a host of other ministerial positions, some created especially for him. He was a man who procured propeller airplanes for the fledgling state battling for its life as a young man, and who extolled the virtues of nano-technology six decades later, still at the apex of Israeli political life.

In this long career, Peres became a fixture of Israeli public life, part and parcel of the Israeli establishment. He died a widely respected and beloved patrician and recent former president, a largely apolitical and grandfatherly role. He departs as the very last of the major leaders who were active at the founding of the state and as a symbol of that generation.

Peres was also unusually beloved abroad for an Israeli leader, receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1994 alongside Rabin and Yasser Arafat for the Oslo Accords he had helped orchestrate between Israel and Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organization. Diplomatic doors were open to him—as were Brookings’s—and as president he served as a de facto super-foreign minister. His funeral will be a summit of world leaders not seen in Israel since Rabin’s funeral in 1995.

Peres’s stature abroad was also reflected among ordinary citizens. I have found myself trying to convince friends in Morocco that Peres was not, in fact, a Moroccan-born Jew (there are many in Israel). They were eager to claim him, the former prime minister of Israel, as their own. I have had conversations with Latin Americans, convinced that he (Shimon “Peréz”) was in fact theirs. Yet Peres was born very far from Latin America (his name, which he chose, is properly pronounced “Péres”, with a soft S.) And was, in a way, the “opposite” of Moroccan in Israeli societal and political terms. He was born Shimon Perski, in Poland (now Belarus), and had the Polish accent to prove it.

Peres’s outsider origins, ever the immigrant, would follow him throughout his career.

While he became an essential part of the Israeli leadership for decades, Peres’s outsider origins, ever the immigrant, would follow him throughout his career. Battling with political rivals in Labor—Rabin chief among them—and in the Likud—Begin, Shamir, Netanyahu—he was also handicapped by his lack of military experience. Though as an official he had helped create early Israel’s nascent air power, fathered its nuclear deterrent, and procured its arms supplies in its moments of dire need, he remained someone who had not himself fought in combat. Being an immigrant, like the older generation of Zionist leaders, he was also an outsider to the group of “Sabras,” native born sons of the pre-state Jewish community, like Rabin, Yigal Allon, and Moshe Dayan. They, the heroes of 1948, were fighting, at times, with the arms Peres had worked to provide them.

Peres also embodied a dramatic transformation from ideological hawk to dove, common among several Israeli leaders. Early in his career, in the ministry of defense, he was central to the efforts to broker an alliance with France and Britain that culminated in the 1956 Suez War against Egypt. In the 1970s, as minister of defense under Rabin (in his first term as prime minister), Peres was instrumental in helping the Gush Emunim movement establish its first settlements in the northern West Bank (Samaria, as Israelis often refer to it). Yet after assuming the party leadership and interacting with other social-democratic leaders around the world, Peres began a steady move to the left. By the late 1980s he had become Israel’s most senior dove. As foreign minister in a national unity government with the Likud (1986-1988) he attempted to broker a far-reaching deal with Jordan over the future of the West Bank, secretly meeting King Hussein and concluding the “London Agreement,” against the wishes of Likud Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir.

Always entrepreneurial in his diplomatic endeavors, and willing to take considerable risks to re-shape reality, Peres oversaw the early Oslo negotiations as foreign minister in Rabin’s second term. In fact, on November 4, 1995, when an Israeli assassin murdered Rabin over the Oslo Accords, the assassin’s goal was to murder Peres as well. Peres would live for another 20 years, but the peace process he was so instrumental in leading never fully recovered.

Peres’s long and illustrious political career was marred by his failure to win national elections outright, yet he was elected to the post of prime minister in an odd draw in the elections of 1984. With no conclusive result, Peres and Shamir joined together in a national unity government brokered by Ariel Sharon, another future prime minister. Peres assumed the role of prime minister for the first two years and implemented one of his crowning achievements, not in diplomacy or peace, but in domestic economic policy.

In 1985 he oversaw an emergency economic plan that brought Israel back from the economic brink. Inflation under the previous Likud governments of Begin and Shamir had risen by 1984 to a crippling 444 percent annually (not a typo), alongside an unsustainable deficit. In an emergency plan, the government introduced stringent but temporary price controls, a new currency (the New Israeli Shekel, which shed three zeros from the Shekel, which had been introduced only five years earlier), and newfound discipline in the country’s balance of payments. There, in the halls of government policymaking, Peres’s tendencies toward compromise and pragmatism served him and his country best.

Peres…was a very young 93 year-old, an eternal optimist.

A man of so many different achievements and battles in the span of over seven decades, Peres’s life represents the full journey of Israel itself, from its founding, when he, the immigrant, was already active in public life, through its 60th Day of Independence, over which he presided as the country’s president. He was as complex and full of contradictions as the vibrant society he served.

Peres, as was apparent to anyone who met him, was a very young 93 year-old, an eternal optimist, always speaking in distinctly-Peres aphorisms about the future, vision, hope, and the promise of youth. He could seem naïve to some Israelis, especially when the promise of peace and a new, hopeful Middle East faltered. Yet through all the pitfalls of his pursuit of peace, and the disappointments and tragedies that accompanied his journey, he remained a believer in the possibility of coexistence between Israel and its neighbors and in Israel’s potential to transform its reality for the better rather than succumb to cynicism and passivity. His was a voice and a tone that is scarce in contemporary Israeli and Middle Eastern discourse, and it will be missed even more now, with his passing.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Shimon Peres: Eternal optimist, 1923-2016

September 28, 2016