The civil rights era was focused on overturning legal racial segregation and practices that were developed to exclude Black Americans from equal access to public facilities and equal protection under the law. On Dec. 1, 1955, Rosa Parks became part of the larger social movement for Black equality by refusing to give up her seat on a public bus in Montgomery, Alabama. On that day, Parks not only defied the Jim Crow laws enforcing segregation—her courageous act became a powerful symbol of the transformative change needed to reshape the course of American civil rights. In fact, her quiet yet assertive act of protest ignited the modern Civil Rights Movement and led to various legal victories, including those leading up to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Yet for all of this progress, the year 2025 alone has witnessed the upending and potential challenging of many of the foundational civil rights gains that Parks and others fought for and won. The Trump administration has launched a vicious attack on voting rights protections and encouraged the return of racial gerrymandering in the rewriting of electoral maps. Under this administration, K-12 and higher education have experienced the dismantling of student protections and the undermining of equal educational opportunities. Rollbacks in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts across the public and private sectors have led to more than 300,000 Black women losing their jobs, undermining the progress Black Americans have fought for. Seventy years after Rosa Parks’ historic act in 1955, the Black community—and all who stand in solidarity—must reflect on how Parks’ legacy can be revitalized to safeguard American democracy and the hard-won rights of Black Americans.

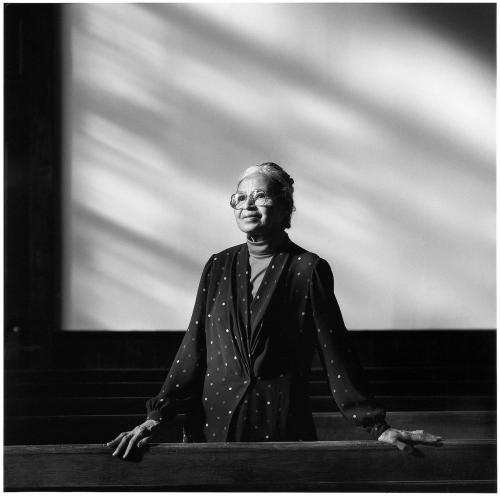

Rosa Parks and the spark of the Montgomery Bus Boycott

It was Dec. 1, 1955—the beginning of the massive Montgomery Bus Boycott and a pivotal time to advocate for civil rights.

Three months before Parks’ protest, Emmit Till was abducted and murdered by white supremacists in Money, Mississippi. His death was symbolic of how Black people were viewed and treated in the South despite historic legal wins, including the U.S. Supreme Court’s rejection of the separate but equal doctrine in its Brown v. Board decision in 1954. The Brown decision overturned a 60-year precedent established by Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld segregated schools, hotels, buses, railcars, water fountains, movie theaters, restaurants, department stores, and other public spaces. This was the daily reality for Parks and many others; she understood the moral and legal call to action that was needed to upend legal racial segregation. Additionally, Blacks in the South were growing impatient with the progress toward equal protection under the law, dismantling Jim Crow, and began to form organizations designed to combat voter suppression and other tools of segregation. Organizations, such as the Women’s Political Council (WPC) in Montgomery, Alabama, centered their work on challenging everyday forms of segregation, including racial discrimination on buses, voter registration, and access to public resources such as parks, schools, and libraries supported by tax dollars.

In 1955, Black residents of Montgomery made up 75% of the bus passengers, yet they were forced to sit in the rear section; after paying their fare at the front of the bus, Black people were forced to board through the rear door. White passengers often yelled derogatory and demeaning insults at Black riders during bus rides. Parks had previously resisted giving up her seat in the 1940s, and other Black women had been arrested for the same act protest, such as 15-year-old Claudette Colvin. However, civil rights “test cases” challenging segregation policies required “perfect” litigants, and Parks’ defiance was an intentional act. Parks was viewed as a model freedom worker who worked alongside the local NAACP chapter and the WPC to eradicate the indignity many Black Southerners experienced in public spaces and transportation.

Parks was an extraordinary Southern Black woman. She was a seamstress who worked on voter registration campaigns, served as a field secretary for the NAACP in Montgomery, helped train young people for collective action in the NAACP’s Youth Council, and, together with her husband Raymond Parks, actively fought to end racial injustice. The arrest of a respectable married church member with an unblemished character for not moving to the “colored section” of the bus galvanized civil rights strategists in Montgomery to launch the bus boycott. As the boycott stretched on for months, Black and white citizens, organizations, and newspapers sustained the cause financially and through coordinated communication. This collective effort became a powerful symbol of community-driven transformation, spotlighting the urgent need to end legal segregation, dismantle white supremacy, and challenge voter disenfranchisement. On Dec. 21, 1956, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., along with other civil rights leaders and Montgomery residents, boarded the city’s first desegregated bus. That same year, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Browder v. Gayle outlawed bus segregation.

The boycott became an emblem of nonviolent social action, demonstrating the economic leverage of collective protest and amplifying the call for racial justice. Yet the Montgomery Bus Boycott is often remembered as a single historic moment, while many other acts of civil disobedience—and the Black grassroots organizing that sustained them—fade from view. Organizing goes beyond community engagement or the forging of social ties to achieve a common goal; it is not a one-time act or donation. True organizing demands sustained commitment, collective clarity about the mission, and a deep understanding of the community’s needs.

In Montgomery, this work required deep and sustained capacity in the form of financial resources, time, leadership, diverse voices, representation, and strong communication networks to launch a year-long campaign aimed at pressuring resistant policymakers across all levels of government. It also directly challenged the economic stability of the Montgomery City lines, the local bus company, and the broader social order that relegated Black Americans to second-class citizenship. Many recall this period as one marked by hostility and fear, when racial tensions ran high and violence could be easily provoked. The boycott emerged as a defining model of nonviolent resistance, inspiring similar protests against injustice nationwide. It helped unify communities in their pursuit of change, momentum that would continue to propel the Civil Rights Movement forward.

Parks’ legacy today

Seventy years later, Parks’ legacy remains unmistakable, but her significance for Black women has been nothing short of extraordinary. In a movement long dominated by men, the priorities and leadership of Black women have increasingly moved to the forefront of policy debates on equal rights, opportunity, and justice. The Civil Rights Movement helped pave the way for a dramatic rise in Black women serving as elected and appointed officials, holding seats across local, state, and federal courts, and leading major civic organizations and businesses.

The fight for civil rights has never ceased, and economic boycotts remain a powerful tool. In February 2025, activists launched a new boycott targeting companies that rolled back their DEI policies under pressure from the Trump administration and its executive order ending so-called “illegal DEI.” Much like the Montgomery Bus Boycott, today’s organizers have built a broad coalition challenging corporate leaders, institutions, and major organizations to uphold fair and equitable practices. Customers, like voters, have choices—and both politics and purchasing power tend to align with the values and policies that reflect people’s identities, even when those identities are threatened or undermined by the executive branch.

In the modern era, the fight for DEI and equitable treatment has grown even more challenging as companies align themselves with the policies and political climate shaped by the Trump administration, all while core civil rights protections come under attack. The president has issued multiple executive orders targeting DEI practices and taken additional steps that reduce Black representation, including dismissing several Black government leaders and pursuing legal action against elected officials such as New York Attorney General Letitia James. These inequities risk becoming further entrenched as cases advance through the courts, with the possibility of the U.S. Supreme Court codifying them as legal challenges continue to mount.

Rosa Parks’ life and legacy are permanently woven into the fabric of American history. Her unwavering commitment to justice helped expand opportunity for all, including those who later come to this country seeking freedom and possibility. Her story underscores the essential role of collective action in confronting injustice embedded in law, and the power of ordinary people to spark change when government fails to act. Leaders like Parks ignited the torches that advocates still carry today as they work to confront the enduring effects of segregation, hold institutions accountable for retreating from equity, and urge the government to sustain programs that communities continue to depend on.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Rosa Parks: Lessons learned for the future of civil rights

December 10, 2025