College major choice is a high-stakes decision frequently discussed by economists and policymakers because of the significant, long-term impacts of major on a student’s financial success after graduation. While substantial attention has been paid to policies designed to increase the share of women in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields, few have noticed the growth over recent decades of a new racial disparity in college majors, driven not by students’ preferences but primarily by tightening “major restriction” policies imposed by universities.1

We quantified this trend in a new study by constructing an index of majors’ average “wage premium” to capture the wage disparities that come with major selection. We show that racial and ethnic stratification across majors has increased in the last 25 years, with students from underrepresented minority groups (URM: Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native) increasingly concentrated in lower-wage majors.2 The spread of major restriction policies, which effectively impose additional requirements for admission to particular majors after a student has already matriculated, is a key contributor to this trend. These restrictions impose real costs on students who are excluded and, as we describe, have no clear benefit other than saving universities from having to hire faculty in fields experiencing rapid demand growth. Major restrictions have also contributed to the stalled progress in overall STEM degree completion in the U.S. and in addressing racial disparities in STEM.

Our research leads us to several recommendations for how states and universities can address this growing gap. Funding for state colleges could be increased so that capacity in popular majors can be expanded, but even without new funding better approaches are possible. At a minimum, colleges need to be more transparent about requirements for majors so that students can incorporate this information when they choose a college and prepare for their chosen major. Policies hoping to promote equitable access to desirable colleges, not to mention students’ own efforts throughout their educational careers, are undermined when students are not allowed to pursue their preferred course of study. Universities can and should find better ways to manage enrollment and staffing in high-demand majors.

Majors have become more stratified by race

Many factors other than college major influence how much a student earns, and wages of graduates from a given major can vary widely. In our research, we estimate a simple major-specific “wage premium” to capture the relative earnings associated with each major. This measure captures about how much more (or less) a student might expect to earn depending on the major they complete. We then calculated the average wage premium in majors completed by URM and non-URM (Asian and white) students.

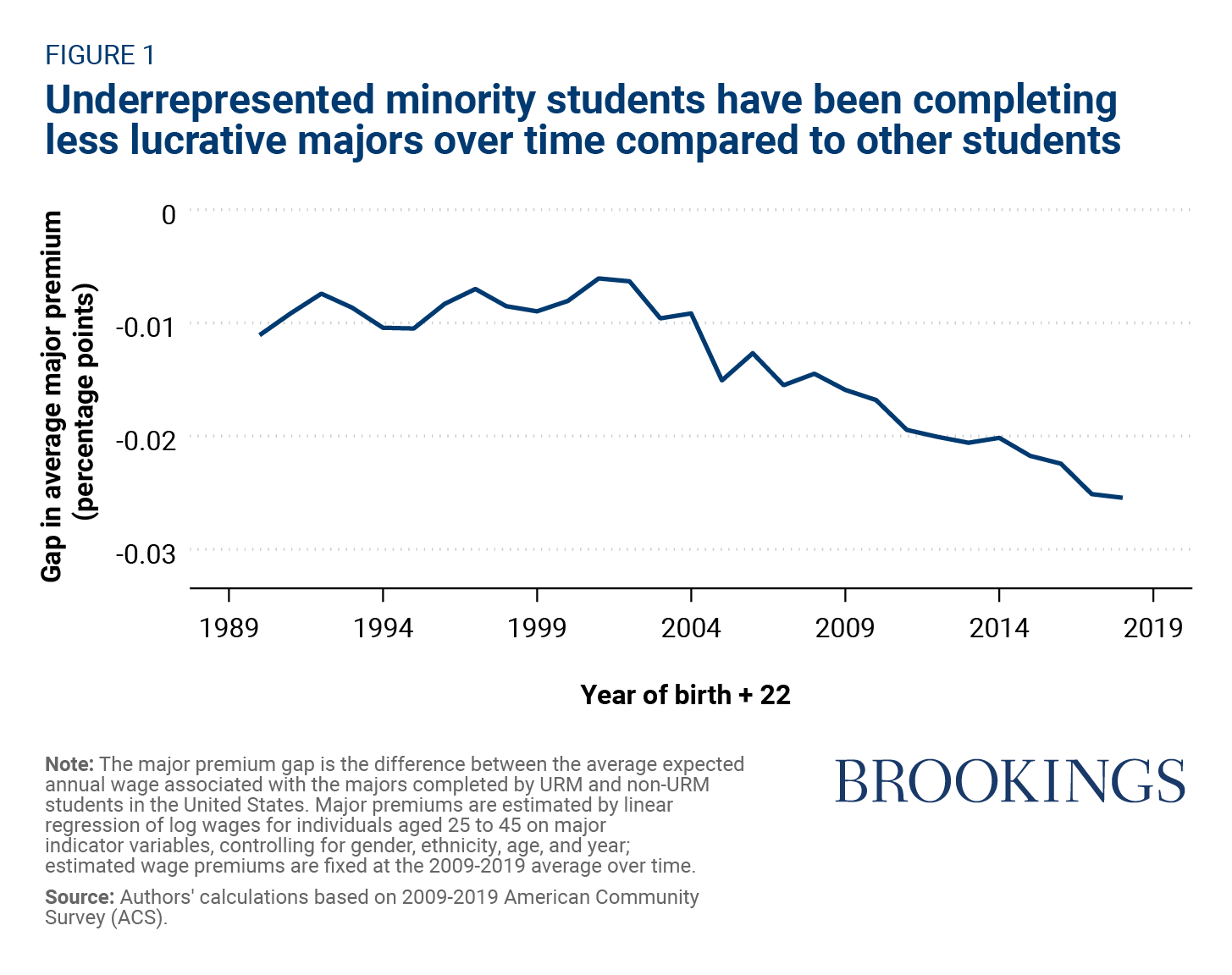

Figure 1 shows how the wage-premium gap between URM and non-URM students has evolved since 1990. In the 1990s, the average wage premium of URM students’ majors was less than 1% lower than that of their white and Asian peers. That gap has tripled since the early 2000s, implying that recent URM college graduates’ college majors alone may be widening the wage gap between URM and non-URM graduates by about 2.5%, or about 10% of the average wage gap between these two groups. The gaps are larger among graduates of public universities, and non-URM graduates at some University of California campuses are earning college majors with as much as 8% higher expected wage premiums than the majors earned by their URM peers.

Changes in student preferences or preparation don’t explain trends in stratification by major

If URM students’ major choices are voluntary, driven by changes in their preferences or aspirations, then perhaps no policy response to the trend in Figure 1 is required. Or if the trend is due to differential changes in pre-college academic preparation among URM students, then improving pre-collegiate learning opportunities or increasing URM students’ enrollment at universities where they tend to earn higher-premium majors may be the best strategies.3

Our study finds no change in URM students’ preferences for high-premium majors relative to those of non-URM students, and their academic preparation has only improved compared to non-URM students. Further, while URM students have increasingly enrolled at universities that tend to award degrees in somewhat lower-premium college majors,4 these changes explain about a third of the rise in college major stratification since the late 1990s. Most of the rise in racial stratification across college majors is not due to shifts in enrollment across institutions but instead has occurred within large selective public universities where URM students have enrolled for decades. That is, this rise in stratification largely originates from campus policies affecting access to majors for students who have already matriculated at the institution.

Major restrictions are increasingly ubiquitous

“Major restrictions” are policies that require students to submit a competitive application, participate in an interview, or meet GPA requirements in introductory courses to enroll in a particular college major. These conditions may be relatively benign to students who are well-situated to succeed in their first year of college, but they present significant barriers to less-privileged students: These students may have difficulty adjusting to the demands of college classes and life on a college campus; their K-12 education may not have prepared them to obtain high grades in their first year on campus; and they may struggle financially, making it impossible to pay for tutoring or protect their study time. Students from URM backgrounds are more likely to face these challenges and are therefore more likely to be limited by major restrictions.

Major restriction policies take one of three common forms at American universities:

- In-major mechanical restrictions require students to achieve a GPA in the major’s introductory courses above a minimum threshold;

- Overall mechanical restrictions require students to achieve an overall GPA in their first year or two of college above a certain threshold; and

- Discretionary restrictions require students to submit a competitive application to the department; what criteria departments use to review the applications varies and is often not transparent.

A tiny number of majors are only available to students directly admitted into the programs from high school, which is a popular policy internationally but rare in the U.S.5 All other departments are considered unrestricted.

The economics major at the University of California, Santa Cruz provides a useful example of an in-major mechanical major restriction.6 After the financial crisis, when demand for the economics major surged, students who wanted to declare UC Santa Cruz’s economics major had to earn at least a 2.8 average GPA in two specific introductory economics classes. While an appeals process allowed some low-GPA students into the major, the restriction pushed most into other lower-premium social science majors. Overall mechanical restrictions work in a similar manner but are based on average grades across more courses. Notably, students who are versed in the “hidden curriculum” of how colleges work (or have access to good advising) may “game” the system by choosing courses that make it easy to meet the GPA threshold for their intended major.

To better understand how common restrictions are in American higher education, we collected data on the major restrictions implemented at the 106 public universities with an R1 research designation; the R1 status indicates a high level of research activity, and these institutions also tend to be the more-selective and better-resourced schools in their states.7 These 106 universities conferred 31% of all U.S. bachelor’s degrees in 2021, in 10,375 different college major programs.

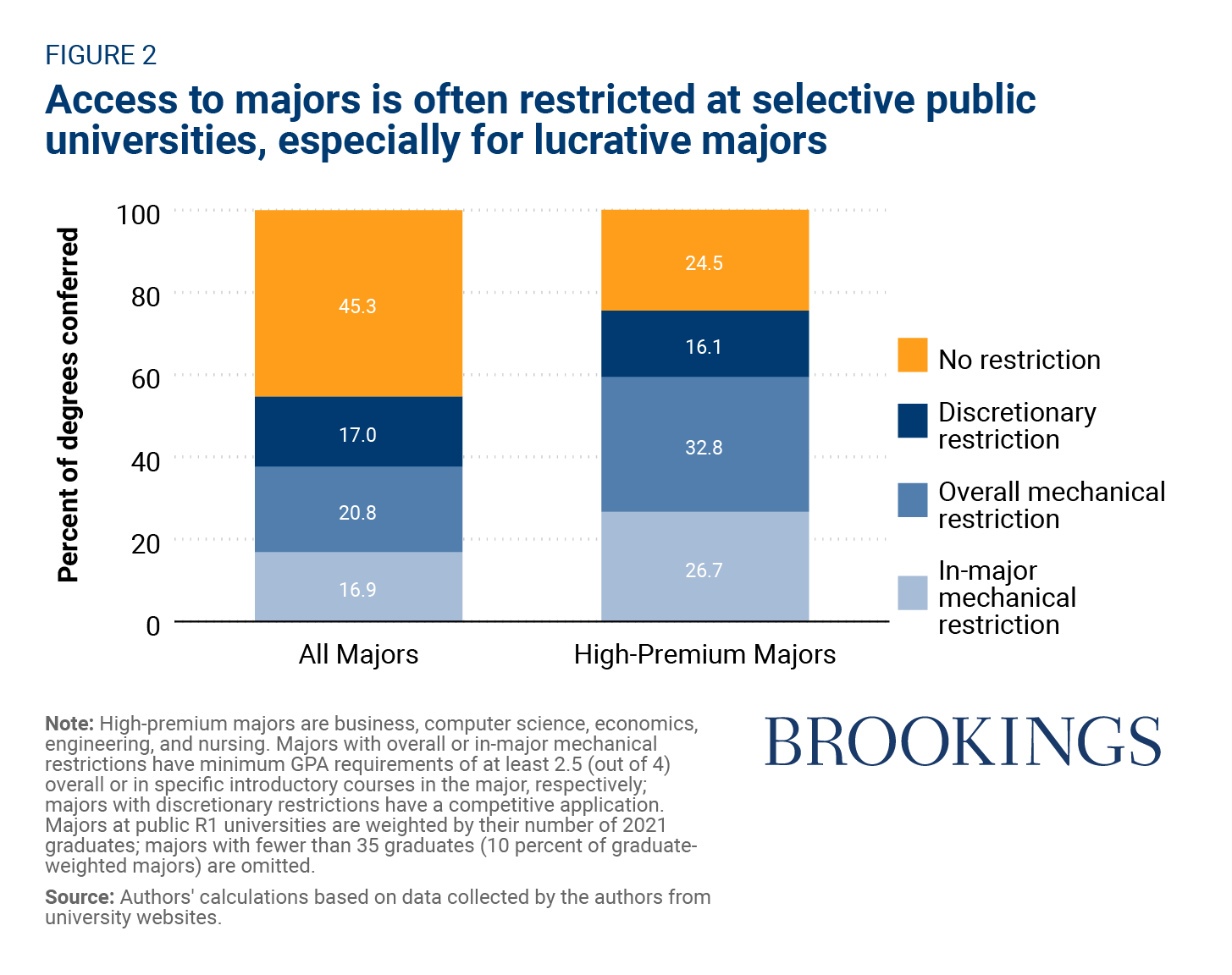

Figure 2 shows the ubiquity of major restrictions at these public R1 universities. The first bar shows that about 55% of students who earned undergraduate degrees at public R1 universities had to overcome a major restriction to do so. One-third of students completed majors with minimum GPA requirements in the major’s introductory courses or an application for admission to the major, with another 20% needing to meet an overall GPA threshold (an overall mechanical major restriction).

The second bar focuses on the majors whose graduates tend to earn the highest wages—those in business, computer science, economics, engineering, and nursing. Access to these majors is even more restricted: Three-quarters of graduates had been subject to a major restriction in their chosen major, including over a quarter of students facing explicit GPA cutoffs in specified introductory courses. The share of high-premium majors at top public research universities that impose mechanical or discretionary major restrictions has increased by over one-third in the past 20 years.8 These data suggest that major restrictions are most binding in the college majors that provide students with the strongest long-run economic outcomes.

Major restrictions affect disadvantaged students most and push students into less-lucrative majors

Our analysis of the impact of major restriction policies at four University of California campuses found that major restriction policies reduce enrollments among students with below-average academic preparedness and performance.9 Those lower-performing students came disproportionately from disadvantaged backgrounds. This suggests that major restrictions especially impacted students who were admitted to UC because of their academic promise, despite having more limited academic opportunities before college. URM students were three times more likely to leave a major once a restriction was imposed, compared to their non-URM peers, and major restrictions led to a 20% drop in the URM share of students completing those majors, on average. Enrollment among students from lower-income families also declined more in response to restrictions.

What happened to students who were filtered out of restricted majors? Our analysis10 revealed that these restrictions pushed URM students into less lucrative college majors for two reasons: they are more likely to exit the restricted major, and they also tend to opt for even lower-earning alternative majors than their (filtered-out) non-URM peers. The effects of major restrictions identified by the model closely match the real-world data on increasing stratification across UC majors, providing further support for the idea that racial stratification can be largely explained by the spread of major restrictions.

Major restrictions don’t have offsetting benefits

Major restrictions push students—especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds—into less lucrative courses of study, but do they also have benefits? Our analysis suggests they don’t.

Do major restrictions help low-GPA students find majors that better suit them? After all, both mechanical and discretionary restrictions are designed to identify students who do particularly well in the major’s introductory courses and/or exhibit strong interest in the major. But we find that students’ first-year grades turn out to be more a reflection of their overall academic preparation than of their relative strengths in different fields: the same students who earn high grades in, say, chemistry, tend to also do well in literature courses. Importantly, low-GPA students are no less likely to graduate if they’re allowed to pursue the restricted major despite their poor grades.

Does introducing a major restriction improve a department’s quality of instruction or help employers sort and identify highly-productive workers? Perhaps the restrictions allow professors to teach higher-level materials to smaller classes of higher-performing students, and students might directly benefit from having higher-performing peers in their courses. Our analysis finds that the labor market value of degrees awarded by restricted majors is no higher than it had been before the restriction was imposed, rejecting each of these stories.11 In fact, we find that when low-GPA students are permitted to declare lucrative majors, they obtain larger long-run employment benefits from taking those courses than the typical student in the major. That is, major restrictions tend to exclude the students who have the most to gain from completing high-wage college majors. Altogether, the findings suggest that major restrictions are not employer-friendly and do not meaningfully enhance the earnings of graduates in those majors.

Finally, maybe major restrictions benefit the university or the nation by spreading students more evenly across fields of study? Institutions adopt major restriction policies to address their own budget and capacity concerns, but the policies have the net effect of decreasing degree attainment in STEM and other high-premium college majors despite substantial national interest in increasing STEM attainment. Further, there is little reason to think that the economic health of the nation is supported by discouraging disadvantaged students from pursuing lucrative fields of study; society loses when interested students who had limited opportunities before college cannot take full advantage of the economic mobility college is meant to offer.

Better approaches are available

Major restrictions reduce access to opportunity without offsetting benefits. So why do they exist, and what ought to be done instead? These policies have arisen as a response to shifting demand for different majors and public universities’ limited capacity to respond to this given faculty tenure, falling per-student state support, and a responsibility to support research activity and instruction in fields with declining numbers of majors. Major restrictions are a drawbridge that departments can raise to protect faculty research time and class sizes in the face of increasing demand. Our research suggests that dismantling or loosening major restrictions would provide substantial benefits to disadvantaged students and generate a higher return to taxpayer investments in higher education, but the enrollment consequences in impacted departments would need to be managed.

Our preferred solution is to increase public funding for public research universities so that they can hire more preceptors, tenured and tenure-track faculty, and untenured instructors to meet demand for high-return majors. Policymakers and institutions could look for ways to meet their research and teaching missions separately, through separate teaching- and research-focused hiring lines. Clear empirical evidence shows that lecturers and teaching professors are often excellent teachers in lower-division courses, while upper division courses and honors programs are best taught by practicing researchers.

This suggests a compromise: encourage departments to hire a mix of teaching and research professors that matches their lower- and upper-division teaching needs. Departments teaching many majors would hire more research professors, and those teaching more lower-division general education courses would hire more teaching professors. In practice, this would expand teaching-oriented faculty positions in high-demand departments who graduate relatively few majors. In addition to meeting pedagogical needs while permitting the campus to pursue a research mission, this principle for allocating faculty lines would penalize departments that apply major restrictions aggressively to reject students by granting these departments fewer research faculty positions.

Crucially, in implementing such a compromise, departmental interest should be measured by both course enrollments and degree recipients to avoid excessive cuts in humanities departments with declining attainments but more persistent enrollment. This change would expand student access, reduce stratification, and potentially increase both economic growth and mobility. These reforms would need to be balanced against universities’ broad research priorities, changes in campus culture that could arise from shifting enrollments, and internal political frictions among university faculty.

If major restrictions must remain in place for enrollment management purposes, steps can be taken to reduce their adverse effects. Strict GPA cutoffs should be avoided in favor of discretionary restrictions based on an application or holistic evaluation as in undergraduate admissions. This would allow departments to evaluate students in the context of their prior academic opportunity and personal circumstances.

Transparency regarding major restrictions is also badly needed. Most universities do not prominently display or aggregate their restrictions for specific majors, and many students don’t know about restrictions until it is too late to fix a low GPA or make other preparations. Universities (or state or federal governments) could address the problem by creating a standard way for students to view restrictions across all majors, like UC Irvine does. This could be coupled with outreach and advising to inform students about major restrictions before they even arrive on campus.

Finally, the disparate impact of major restrictions on students who had more limited pre-college educational opportunities could be mitigated by targeting additional advising and academic support to students with low GPAs in their first semester so they can get back on track for the major they prefer.

Conclusion

Restricting access to certain majors unnecessarily pushes students from disadvantaged backgrounds into lower-earning majors, undermining public universities’ mission to promote economic mobility. The impacts of these policies can also be felt at the societal level, with individual impacts – especially in STEM fields – translating into reduced economic innovation and growth. Universities should replace these policies with less restrictive and/or less stratifying alternatives.

-

Footnotes

- An important 2020 report by the Urban Institute was the first to document growing ethnic segregation in major completion, following a 2015 report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland documenting differences in major choice by ethnicity. Our work has complemented those findings by showing that URM students do not merely complete different majors from their non-URM peers; they complete lower-earning majors largely as a result of major restriction policies keeping them out of lucrative majors.

- A recent study by economists at the University of Chicago shows that gender stratification across college majors has remained unchanged for decades, with female students earning persistently lower-premium majors than their male peers.

- Our studies of major restrictions and affirmative action have both shown that students who enroll at more-selective and higher-investment universities tend to be more likely to earn high-premium college majors.

- This shift to institutions where low-premium majors are more common is largely attributable to state affirmative action bans and the rise of for-profit universities.

- Some programs admit most of their students directly from high school but also allow other students to switch into the major through a major restriction policy. The University of Washington’s computer science major, for example, prioritizes its “Freshman Direct to Major” pathway but admits about 30 percent of enrolled students who wish to switch into the department.

- This policy was first introduced in response to skyrocketing increases in demand for the economics major during the Great Recession. In an earlier paper, we show that losing access to the economics major caused low-GPA students to earn far lower wages after leaving Santa Cruz than they would have earned if they were permitted to study economics at the university.

- We examined the institutions’ websites and course catalogs to identify restrictions implemented in majors that graduated at least 35 students in 2019, which included 4,408 total majors that awarded 90% of those universities’ degrees in that year.

- The historical data cover the five most lucrative majors at the 25 most selective public universities rather than the full set of institutions and majors shown in Figure 2.

- We compare the sociodemographic characteristics of the students who declared certain college majors in the years before and after those majors implemented restriction policies using a staggered difference-in-difference design to examine major restrictions at the University of California campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Santa Barbara, and Santa Cruz, where our anonymized student records generally spanned 1975-2016.

- To examine this question, we use a machine-learning model to identify the students who intended to major in restricted fields based on the courses they took in their first term and then examined which fields students intending a major selected after a restriction on entry into that major was introduced. See the paper for details.

- Restrictions are often cited as important tools to ensure that graduates with these majors will perform well in the workplace, an argument that would be compelling (if true) in certain fields like engineering or nursing. But we find no evidence of these potential benefits in the typical cases where restrictions are imposed.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).