Editor’s Note: The following is a Campaign 2012 policy brief by Martin Baily proposing ideas for the next president on stimulating America’s economic growth. Karen Dynan prepared a response arguing that the housing finance system must be reformed in order to introduce greater certainty into the market. Elisabeth Jacobs also prepared a response arguing that the next president should act forcefully to promote economic security and opportunity in America.

Introduction

James Carville famously remarked of the 1992 election that “It’s the economy stupid!” and the same will be true of the 2012 election. When President Obama came into office, he embraced the challenge of turning the economy around. The policies he followed to stabilize the banks and provide stimulus to a tumbling economy were the correct ones and succeeded in stopping the collapse. Unfortunately, Obama and his economic team were overly optimistic about how fast a full recovery could be achieved. An extended period of slow growth was inevitable, given the severity of the crisis and recession. There should have been a more single-minded focus on the recovery, and the administration’s ambitious policy agenda in other areas should have been scaled back.

Republicans are blaming Obama for the continued economic weakness, which they say is caused by excessive government intervention. It seems delusional to blame the 2008 financial crisis and resulting recession on too much regulation, but Obama’s policy overreach has made it easier to paint him as an advocate of big government. His re-election will depend heavily on whether the economic recovery strengthens or weakens in 2012.

The immediate problem facing the economy is weak demand. Recovery is under way, but it continues to be slow and it could falter in 2012. It will need to be nurtured, both in the remainder of this administration and in the next presidential term. Given the budget crisis, there are limits to what more can be done with federal spending, but I lay out here eight important steps to restore growth:

- Continued stimulus for workers’ incomes;

- Maintaining assistance for housing;

- Providing continued aid to the states;

- Controlling the trade deficit;

- Helping Europe address its debt crisis;

- Setting a framework for a balanced budget;

- Encouraging states to bring in private capital to undertake significant

infrastructure investments; and - Embracing the trends of developing educational technology and expanding competition among educational institutions.

The Obama Record

[1]

The financial crisis started in 2007 and evolved into a full-blown recession by 2008, with the rate of job decline hitting a high point with over 700,000 private-sector jobs lost a month November 2008 through the spring of 2009. Private sector payroll employment fell 8.8 million from its peak to its trough. The financial crisis and severe recession were deeply damaging, and no president has the power to turn around the economy quickly. The U.S. economy bounced back pretty quickly from severe recessions in 1975 and 1982, but those recessions were very different. The job loss in this recession was far more severe, and the bursting of the housing bubble left a legacy of trillions of dollars of lost wealth, underwater mortgages, weakened banks, slow growth in wage incomes and a collapse in residential construction.

The fiscal policy of the Bush administration tied Obama’s hands in dealing with the recession. President Bush inherited an FY 2000 budget surplus but ran large budget deficits from FY 2002 through 2008, including a 3.2 percent of GDP deficit in his last year. These deficits limited the size and duration of the stimulus policies available to overcome the collapse of private demand.

Given the limitations they faced, the Obama economic team and Federal Reserve deserve great credit for rescuing the financial sector and pushing through a substantial fiscal stimulus. Credit also the Paulson Treasury that started the bank rescue program. Neither the bank rescue nor the stimulus package was pretty; in fact, they were pretty ugly. But they did what they had to do in stopping financial sector collapse and contributing to a sharp economic turnaround, where GDP went from a nearly nine-percent rate of decline in the fourth quarter of 2008 to a growth rate of well over three-percent by the fourth quarter of 2009 and the first half of 2010. The bank stress tests were particularly important in establishing the amount of capital needed and making sure it was available. Both the broad economy and status of lower-income Americans would have been much worse had there been no financial rescue. It took courage and judgment to rescue the banks and stimulate the economy.

Given the severity of the economic crisis, Obama should have told Americans when he came into office that it would take several years for a solid recovery to take hold; that the recession and the responses to it would trigger very large budget deficits and that many of his signature programs would have to be postponed until recovery was certain.

Budget deficits have become a huge issue. There were estimated budget deficits of $1.4 trillion in 2009, $1.3 trillion in 2010 and $1.3 trillion in 2011. The amount of federal debt held by the public rose from $5.04 trillion in 2007 to $10.16 trillion in 2011, equal to 72 percent of GDP. With the interest rate on 10-year Treasury securities hovering around two percent, there is no evidence yet that global financial markets are pricing in a significant risk of Treasury default. Still, the path of budget deficits is not sustainable for much longer, and fiscal consolidation will be needed.

Obama established the Bowles-Simpson commission and tasked it with coming up with proposals to achieve long run fiscal sustainability. When the commission reported, however, he largely ignored its findings, and he did not embrace an alternative proposal or come up with his own plan until very late in the day. The explosion of the debt and deficit has contributed to the loss of voter confidence in the administration. The next president will need a solid plan to eliminate the budget deficit, not right now, but over the next 10 to 15 years.

The Republican Response

The Paulson Treasury Department in the Bush Administration gets credit for initiating the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) and realizing that massive federal intervention was needed to stop the financial collapse. The problems in letting markets self-regulate were sharply revealed by the financial crisis and subsequent recession, and Paulson favored a more pragmatic and less ideological policy approach than was evident earlier in the Bush administration.

In the first two years of the Obama administration, there were moderate Republicans who were willing to be bipartisan, and it looked as if a financial reform bill could be agreed to by both parties. A bipartisan bill would have been much easier for American voters to support. In the end, however, the Republican leadership decided it was more important or more expedient to oppose Obama than to work together to create a better and much-needed program of financial sector reform and they pulled out of negotiations and voted against the Dodd-Frank bill.

Republicans have expressed concern about the enormous federal deficits, a concern I share, but their commitment to lower deficits is undermined by their refusal to consider any substantial revenue raising options. Fully 238 U.S. House members, 41 senators and all the GOP presidential candidates except one have signed Grover Norquist’s no-increases-in-taxes pledge, thereby declaring their unwillingness to deal realistically with the long-run deficit problem. Take the best possible reform of Medicare/Medicaid and Social Security that is acceptable to American voters. Take the biggest cuts in defense spending that are acceptable. Make sharp cuts in the rest of discretionary spending, and you still need additional revenues to tackle the deficit problem.

The Republican frontrunner is Mitt Romney, and much of his economic program involves blaming Obama. He argues that the bad economy has been caused by a surge in regulation and the sharp increase in federal spending. Ironically, Romney’s plan was authored by Glenn Hubbard, a talented economist but also an important architect of the George W. Bush administration policies that contributed to, even perhaps caused, the crisis and recession.

Based on his record as a moderate governor of Massachusetts, Romney could become a conservative but sensible president. His successful business background shows he has experience in running an organization. In order to gain the nomination, however, he has put forward an economic plan that involves substantial new tax cuts, getting rid of the Dodd-Frank financial regulations, ending federal support for expanded health care, making large but largely unspecified cuts in federal spending, and pushing for a balanced budget amendment. We can hope that he would not be a prisoner of his own rhetoric if he becomes president and that his economic advisors learned something from the Bush administration’s mistakes.

Policies to Revive Growth

The economy has been trapped in a vicious cycle where companies’ sales are growing so slowly that hiring is limited. The resulting lousy labor market means slow growth in household income. With incomes growing slowly if at all, household debts still high and the value of houses depressed, consumer spending is weak, perpetuating the cycle of weak demand. The overhang of excess housing and high consumer debt are two anchors weighing down the recovery and making it harder to break the vicious cycle.

Recent popular books[2] have suggested either that the weakness in jobs and growth is the result of a slowdown in the pace of technological advance or, alternatively, that the opposite is true and that technological change is proceeding so rapidly that it is making work obsolete and increasing structural unemployment. Neither of these views is convincing as a description of our current problem. Productivity growth in the non-farm business sector of the U.S. economy has been in the range of 2.0-2.5 percent for the past 20 years, so there is no sign of big swings on the supply side of the equation.[3]

Technology and innovation, broadly understood, are having and will have a massive influence on long-term growth and the nature of work. Stimulating science and technology is an important role for policy, but demand is the big issue right now and the focus of this paper.

Despite the weak job market and their debt burdens, consumers have started spending again, with a moderate rate of 2.3 percent growth over the 10 quarters ending in the fourth quarter of 2011. Overall growth in the first half of 2011 was very weak, but second-half growth was a solid if not exciting 2.4 percent, so the key question is whether that pace will flag in 2012 or pick up.

Toward that end, there are eight key steps that both the current and the next president—be that Obama or a Republican who defeats him—should take:

Continue the Stimulus for Workers’ Incomes

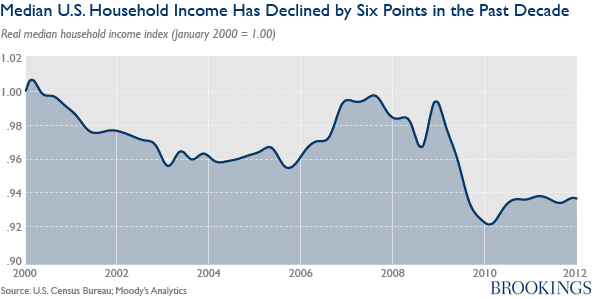

As the chart below shows, the recession has caused a large drop in median real income, a drop that we know is across the board, for households ranging from 25 years old to 65 years old.[4] These are the households that depend on wages and salaries, and they have been badly hurt. The top priority for economic stimulus is to get additional funds to these low- and moderate-income families.

The struggles between Congress and President Obama have made it hard to enact even a modest fiscal stimulus, given concerns about the deficit. However, the 10-month extension of the payroll tax cut Obama signed into law on February 22 guarantees workers $1,000 of additional take-home pay for the year, and the legislation also extends unemployment benefits.

If growth remains very weak through 2012, it would be necessary to extend that tax cut into 2013 and if there is a double-dip recession in 2012, then the next president will have to go further by adding additional income support measures. One approach would be to mail a $1,000 tax rebate check to all taxpayers (adjusted for singles or couples and phased out for high-income filers). Such a measure would carry some danger of triggering instability in financial markets, but a prolonged double-dip recession would add to the deficit also, so the risk would be worth taking.

Assistance to Housing

If there were a good way to turn the housing market around, that would make a vast difference to the speed and robustness of the current recovery. Various measures have been tried, including measures initiated in the Bush administration through the latest efforts of the Obama administration to make it easier for families to refinance at lower interest rates. The effect of these measures has been modest, however, and it is likely that housing will remain weak in 2012, although the situation is gradually improving.

There are three main reasons why it is so hard to solve the housing problem:

- Nationwide, many mortgages are underwater—currently to the tune of $700 billion. Any serious effort to write down mortgage debt with government funds would be very expensive.

- The underwater mortgages are concentrated in a few states. California has 26.8 percent of such debt, and adding only Florida and Arizona pushes the total to nearly 48 percent. This means that any large-scale assistance would involve a big transfer to those few states and hence would be difficult politically.

- Addressing the underwater mortgage problem would help but would not necessarily revive home building or household spending. The big pool of home equity waiting to be tapped has gone, and the magic attraction of home-ownership has been lost.

Still, it remains important to maintain assistance to the housing market, so that it can continue to heal.[5]

Provide Continued Aid to the States

Declines in state and local spending are contributing to weak demand and forcing cutbacks in education spending, road maintenance, police and fire protection and other social services. There are states that allowed their budgets to grow too rapidly in the boom years and need to learn the lessons of sound fiscal budgeting. In particular, many states failed to make adequate provision for the retirement benefits that had been promised to state workers, and they need to change their accounting and scale back the generosity of those benefits. But, a time of fragile economic recovery is not a time to drive punitive cuts in state budgets. Federal funding and guarantees could prevent declines in state and local government spending from becoming a further drag on overall economic recovery.

Make Sure the Trade Deficit Does Not Explode

The U.S. economy has run large trade deficits since the 1980s driven largely by international capital flows and the resulting structure of exchange rates. In part, the United States has been its own worst enemy by spending more than it produces and borrowing overseas to pay for budget deficits and excess housing. But, foreign countries bear part of the blame also, for being content to accumulate U.S. dollar assets in return for keeping their exchange rates down and their exports high. Countries such as China, Germany and the oil-producing states that run large chronic trade surpluses need to expand domestic demand and move toward balanced trade.

The U.S. trade deficit was running at around six percent of GDP before the crisis. As U.S. demand fell, so did imports, and the deficit dropped to around two percent of GDP. If the deficit moves up to six percent again, this will be a substantial drag on U.S. growth. The president elected in 2012 should take three important steps to avoid this problem:

- Work with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to encourage greater exchange rate flexibility globally, especially in the Asian economies. Some form of sanctions may be necessary for countries that manipulate their exchange rates and run chronic multilateral current account surpluses.[6]

- China, in particular, needs to let its exchange rate appreciate. Public pressure or trade sanctions on China would be counterproductive, but the United States should work with its allies to make it clear that China must maintain external balance. The Wall Street Journal reported March 1, 2012 that China is sharply reducing the proportion of its foreign exchange reserves held in dollars, a possible sign that they plan more currency flexibility. But they are still accumulating reserves at a rapid rate (reserves were $3.2 trillion at the end of June 2011 up from under $1 trillion in 2006).

- Balancing the federal budget over the longer term would greatly reduce the need for foreign financing and help avoid an overvalued dollar.

Help the Europeans Solve Their Crisis

A worsening of the crisis in Europe, with cascading financial failures, would almost certainly trigger a double-dip recession in the United States. A collapse in Europe is the biggest danger to continued U.S. recovery in 2012 and beyond. It is in the interest of Americans that the European financial crisis be resolved or at least contained. For political reasons, the current administration wants to make sure that U.S. contributions to the IMF are not used to “bail out” Europe. This is a serious mistake and the restrictions on use of U.S. funds should be eliminated. U.S. taxpayers would almost certainly be repaid if any U.S. funds are used. Moreover, the policy stance of the United States is discouraging other countries, such as Asia, from helping Europe.

The Federal Reserve has already provided lines of credit to the European Central Bank (ECB) and other central banks to offset the dollar shortage that develops when the euro wobbles. The availability of its Fed line of credit has assisted the ECB as it serves as lender of last resort, at a low rate of interest, to European financial institutions. The Fed is working actively to help stabilize the European crisis. Good for them. It is important to oppose firmly any effort to stop the Fed from doing its work well.

Set the Frame for a Balanced Budget

The chances of getting a realistic long-term plan for budget balance before the election are very small, even though progress towards such a plan would help stabilize global markets and would increase U.S. business and consumer confidence. Both the President and the Republican nominee have an obligation to engage in a realistic, fact-based debate on the budget options facing the nation and this requires acknowledgement of the reality the next president will face: There are two essential ingredients to a realistic deficit plan: increased tax revenues and cuts in the growth rate of federal health care spending.

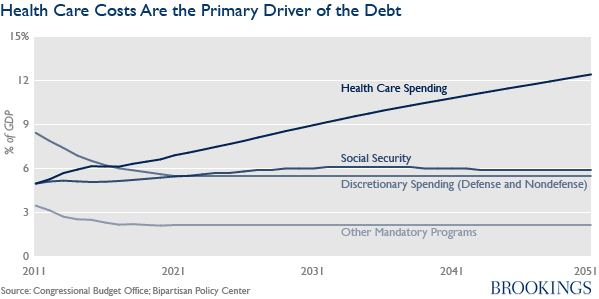

On the spending side, the chart below shows how federal health spending starts to take over total spending in the long run. Health becomes the largest item in just a few years, and moves over 12 percent of GDP over the next 50 years.

Earlier, I criticized the Obama Administration for not doing more on a long-run budget plan but, in fairness, there are important cost-savers built into the health care legislation. In particular, reimbursements to hospitals will be based on cost minus one percent a year, building in an assumed productivity increase. Such productivity increases in hospitals are eminently achievable, based on differences between existing best practices and average practices, or based on the rate of productivity increase achieved in private-sector white-collar industries.[7] The next president should make sure these cost savers remain in place and that Congress does not undermine them.

In order to bring down the cost of outpatient Medicare costs, as well as private insurance costs, it is essential to move beneficiaries away from the current fee-for-service system and the resulting overuse of medical tests and treatments. The best indicator of the problems of fee-for-service comes from comparisons with other countries that have many fewer doctors’ visits and medical tests but have health outcomes that are as good, or better, than those in the United States.[8]

On the tax side, the two leading deficit reduction proposals both spell out plans that could increase revenues without raising statutory tax rates and the next President could use either one as the starting point for a long-run budget plan. In my judgment, there should be a phase-out of deductions for mortgage interest, state and local taxes, and health insurance over an extended period. On the corporate side, the president has introduced a corporate and business income tax reform proposal that could form the framework for a reform bill after the election. Eliminating the distortions of the tax system is important and worthwhile, but the key priority over the next 10 years is to raise revenue to balance the budget. If it is not possible to obtain political agreement on revenue-raising tax reforms, then the next best alternative for the next president is to let the Bush tax cuts expire once the economy is growing strongly.

Infrastructure: Bring in Private Capital and Fund Maintenance

Capital costs are not the constraint that stops good infrastructure projects from going forward. Instead, many good projects lack predictable sources of revenue to service the borrowing costs and, in addition, regulatory barriers make it difficult and costly to actually get them done.

In a recent Brookings forum, Robert Rubin suggested that governors and mayors work directly with private-sector investors and sovereign wealth funds to bring in the capital needed for infrastructure projects. These elected leaders and their staffs can help potential investors navigate the byzantine permission and approval processes. The next president should encourage this, by asking states to develop road, bridge and tunnel projects whose funding is secured by tolls or user fees (preferably tolls that vary with the level of congestion). Another area for investment is the nation’s water and sewer system. Investment there should be funded by supplementary fees on water bills that are earmarked to provide an adequate return to investors. (The fee structure could be set in a way that provides rebates to low-income families.)

It appears that new technology has changed the energy supply situation, especially for natural gas. If environmental concerns can be resolved, there are tremendous opportunities to invest in an improved private-sector-funded energy infrastructure. This could include getting rid of coal-powered electricity generation and developing a national distribution system for natural-gas-powered transportation. The cost of changing the electric power system should be covered through guaranteed user fees, just as in the case of improving the water system.

Regulatory barriers are important, because of the delays and the multiple agencies—federal, state and local—that have to give permission. If this process were streamlined and coordinated and private sector investors were given the opportunity to impose normal cost controls on construction, there would be many infrastructure projects that would attract capital and generate jobs and growth.

I suggested earlier that federal aid to states and localities should be sustained. Some of this assistance should go to much-needed repairs and maintenance of existing roads and bridges.

Improving Education and Skills

There are reports of job vacancies that are unfilled even though unemployment is high because employers cannot find people with the right skills. These reports are surely correct and, although they do not change the importance of demand growth to recovery, there is a good case for finding ways to improve the skill and educational level of the workforce both to reduce structural unemployment and to help break the vicious cycle of low employment and low income.

Improving education and skill training is very hard to do, but there are some encouraging signs of improved performance with new ways to use technology and because competition in education is increasing. Spurred by the efforts of individuals or groups of innovators, there is exciting progress in using technology.[9] Constrained by the lack of skills in the recruits they can attract, the U.S. armed forces are developing short, computer-assisted training modules to equip men and women with the skills they need to operate high-tech (or low-tech) systems. American businesses could learn important lessons from what the military is doing. Charter schools and online universities are of variable quality today but their growth means that competition in education is increasing, which should spur better teaching everywhere. More and more educational material is available online. Today, over 40 percent of Washington DC school children are in charter schools.

The next administration should embrace the trends of rapidly improving technology and increasing competition and avoid setting up roadblocks to change. The Department of Education is already playing an important catalytic role in figuring out what works and what does not. The next president should propose greater transparency, so that students and parents can judge the performance of the institutions they are attending. The President’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness chaired by Jeffrey Immelt, suggested ways to improve the level of technical skills. The next president should go further than they did in trying to get business support for increased training and research into ways to make training more effective. Business should work with community colleges and the armed forces.

Conclusion

There are encouraging signs that U.S. growth is strengthening in 2012. A collapse in Europe or a Mideast oil conflict would disrupt the recovery, but there are steps described here that can be taken to strengthen it. The U.S. economy has been hit harder than any time since the 1930s, but resilience is one of its hallmarks. President Obama and Congress could help growth in 2012, and the next president, whether Obama or his Republican rival, can contribute to a more robust recovery for the long term.

[1] Baily would like to thank Donald Kohn, Douglas Elliott, Ted Gayer, Robert Pozen, Lenny Mendonca and Natalie McGarry for their comments and assistance. Errors and views are my own.

[2] Tyler Cowen, in The Great Stagnation, is the pessimist. Erik Brynjolfsson, in Race Against the Machine, makes the opposite case. Both books are available on iBooks, Nook, or Amazon.

[3] Population and labor force growth have slowed, but these are not the causes of high unemployment.

[4] The figure was prepared by McKinsey & Company. The Company does not endorse specific tax policy proposals. The data on the distribution of the drop in income by different segments of the population was obtained by Sentier Research and their data is proprietary.

[5] My Brookings colleagues Karen Dynan and Ted Gayer have written extensively on proposals to address the housing market. See https://www.brookings.edu/experts/dynank.aspx and https://www.brookings.edu/experts/gayert.aspx.

[6] The “Palais Royal Initiative” made suggestions for ways to strengthen IMF oversight, but more needs to be done in this area. See http://www.elysee.fr/president/root/bank_objects/Camdessus-english.pdf.

[7] See for example, Martin Neil Baily, Karen Croxson, Thomas Dohrmann and Lenny Mendonca, The Public Sector Productivity Imperative (McKinsey & Company, March 2011). There are critics who argue that these cost savings will not be achieved and will be offset by higher administrative costs and I concede that achieving all the hoped-for cost reductions will be tough sledding.

[8] Accounting for the Cost of US Health Care, McKinsey Global Institute, http://www.mckinsey.com/Insights/MGI/Research/Americas/Accounting_for_the_cost_of_US_health_care.

[9] For a review of developments in education technology, see http://thenextweb.com/insider/2011/12/26/in-2011-how-the-internet-revolutionized-education/. See also the webpage of the Brown Center on Education Policy at Brookings, https://www.brookings.edu/brown.aspx.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).