As the deputy chief of the Persian Gulf Task Force at the Central Intelligence Agency in August 1990, I had a front-row look at how President George H.W. Bush handled complex and dynamic foreign policy challenges. Bush was a master at comprehending the intricacies of national security. With his National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft, Bush defended America’s strategic interests in the Middle East, built an international coalition and liberated Kuwait.

Two days after Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) William Webster took me with him to the White House for a National Security Principals meeting on the Iraqi invasion. President Bush chaired the meeting in the Cabinet Room. The DCI was asked to open the meeting with an assessment of the implications of the invasion for the region and American interests. Webster read from talking points I had prepared.

Webster said Iraq now controlled the second and third largest oil reserves in the world (Iraq and Kuwait) and was poised to seize the largest in Saudi Arabia. He had a huge army backed by a massive domestic military industry created during a decade of war with Iran. If the Iraqi leader invaded Saudi Arabia he would overrun the oil-rich Eastern Province and Riyadh in a matter of hours. The Saudis had an understrength national guard brigade to oppose eight divisions of the Iraqi Republican Guard.

According to Bush and Scowcroft’s memoir, the CIA assessment galvanized their own judgement that they must send a military force to Saudi Arabia immediately to prevent further Iraqi aggression. Scowcroft recalled Webster argued the invasion “fundamentally altered” the power balance in the Gulf. Colin Powell, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, wrote later “the CIA Director gave us a bleak status report”—Saddam was in control of 20 percent of world oil and about to take 20 percent more.

Bush decided immediately to secure Saudi permission to host the American deterrent force and to solicit contributions from America’s allies around the world. He began using the phone to call world leaders.

Two days later, Webster and I went to the White House again for an emergency Principals meeting. That morning the Task Force had told the White House that Iraqi forces were preparing to invade Saudi Arabia. The Iraqi forces were in the final preparations for attack, building up logistics to support a rapid assault and moving additional Iraqi armored divisions from Iraq into Kuwait to reinforce the Republican Guard. Bush ordered his secretary of defense to fly immediately to Riyadh to persuade King Fahd that the moment of decision was now.

The Bush-Scowcroft team went into high gear to stop Saddam and rally opposition to the Iraqi dictator. Satellite imagery analysis was crucial to our ability to assess Saddam’s intentions and assess Iraq’s capabilities. Webster instructed me to order every imagery satellite in the American intelligence community to drop all their standing collection targets and focus exclusively on Iraq to get Bush the intelligence he needed.

George H.W. Bush was a voracious consumer of intelligence. A former DCI himself, he had a professional understanding of what intelligence could provide and the crucial importance of policymakers prioritizing what they wanted. He devoured his Presidential Daily Brief every morning.

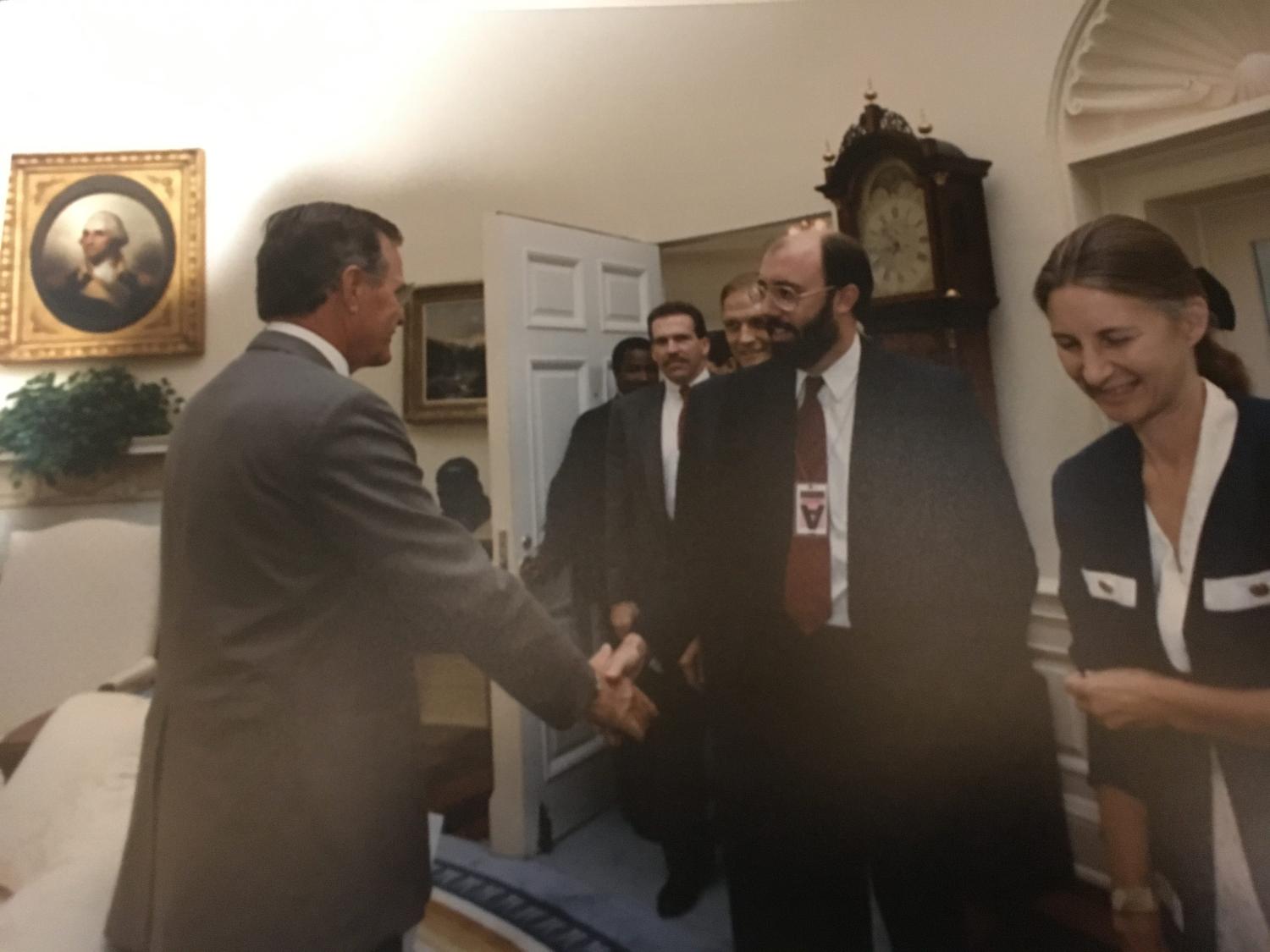

During the build up to Desert Storm, Bush came to CIA headquarters to get briefings on the Iraqi enemy and other topics. It was a great morale booster for people working 24 hours a day sacrificing their personal life for service to the country. Bush had just the right touch with the Agency troops. Several times he invited the community to send experts to the Oval Office for exchanges with him, Scowcroft and his top lieutenants. He encouraged debate and listened carefully to the discussion; grasping that the intelligence evidence was often subject to multiple explanations.

Bush wisely limited the 1991 war to the liberation of Kuwait and not a march on Baghdad. He understood the Iraqi dictator was a spent force after defeat in Kuwait, an irritant not an existential threat. After Desert Storm, I joined Scowcroft’s National Security Council Staff as the director for Persian Gulf and South Asian affairs. I had the great fortune to work with Bush for the remainder of his administration. He was invariably polite and thoughtful as a boss. It was fun and immensely rewarding to work with a great leader.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Remembering George H.W. Bush—A wise foreign policy leader

December 3, 2018