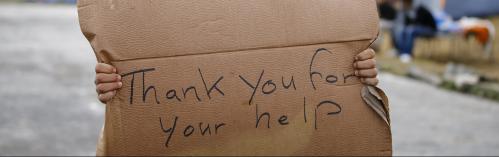

The fear of migrants and refugees, stoked by politicians, is setting a defining narrative for elections in the West. The Brexit vote directly played on these fears as did the U.S. elections with its narrative of Mexican “criminals and rapists,” both setting a tone for electoral victories that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago. The Dutch elections, where the nativist trend grew but was held at bay, also saw much negative rhetoric around Islam. With elections in France and Germany coming up, the trend seems unlikely to abate.

It is worth remembering, however, that while the recent refugee crisis presents an easy target, the social tensions and challenges reflected in these elections are a decades-old phenomenon. The advent of refugees from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan certainly didn’t create these tensions. Nor did the accompanying economic migrants, who sought refuge in a Europe where identity politics had been part of the political landscape for decades. In the meantime, the reality of their links to crime and terrorism have been lost in harsh campaign politics.

During the U.S. campaign, with loud assertions linking migrants and refugees to crime waves, the Sentencing Project noted, “Foreign-born residents of the United States commit crime less often than native-born citizens.” This is echoed by the libertarian Cato Institute, which reported, “All immigrants are less likely to be incarcerated than natives relative to their shares of the population”.

The first comprehensive study in Germany to look at its 1 million refugees, noted, “The refugee influx to Germany in 2014 and 2015 wasn’t followed by a “crime epidemic.” Instead, “there were ‘muted increases’ in some criminal activity in the immediate aftermath of the record influx of refugees, which saw an uptick in drug crimes and fare-dodging in areas with bigger reception centers…also associated with increased minor crime for German citizens—partly explained by increased police presence.”

Research points to an “immigrant paradox,” which isn’t fully understood according to Boston University’s Salas-Wright: “One theory is that people who pick up their lives and move to a foreign country and set up a new life tend… to be interested in making this new life work.” This likely holds true for refugees fleeing war, especially if they are with their family or are anchors for them.

On refugees, migrants, and terrorism, the Migration Policy Institute, noted, “The United States has resettled 784,000 refugees since September 11, 2001. In those 14 years, exactly three resettled refugees have been arrested for planning terrorist activities… two were not planning an attack in the U.S. and the plans of the third were barely credible.” Another study looked at four decades of foreigners coming into the U.S., noting that “the chance of an American being murdered in a terrorist attack caused by a refugee is 1 in 3.64 billion per year while the chance of being murdered in an attack committed by an illegal immigrant is an astronomical 1 in 10.9 billion per year. By contrast, the chance of being murdered by a tourist on a B visa, the most common tourist visa, is 1 in 3.9 million per year.”

What we do know is that from Orlando to San Bernardino and others, U.S.-born terrorists remain a far greater threat. This is also a significant factor in Europe as seen in attacks in Paris, Brussels, Copenhagen, and London. Yet here too it is worth remembering that attacks from radical Islamic groups in Europe are a decades-old phenomenon, long predating the recent influx of refugees and migrants.

The reality is that the challenges of integrating some Muslim youth has indeed provided (a tiny) opening for terrorist recruitment in Europe. Fifteen years ago, the now infamous neighborhood of Molenbeek from where many of the Brussels and Paris attackers came, was known for riots “born out of desperation… in a neighborhood characterized by poor job prospects, bad housing and deficient education”—much like similar outbursts in the U.K., France, and elsewhere. There is also an emerging link between petty crime—another point of call for the disenfranchised and alienated—and terror groups.

Islamic State is now deliberately tailoring its message to appeal to this small subset within the European Union’s 20 million Muslims. According to Professor Peter Neumann from King’s College London, “There is now a perfect fit between these young men and (IS) that has shed any attempt at serious theological discourse.” Alain Grignard, from Belgium’s counterterror agency, says that “Young Muslim men with a history of social and criminal delinquency are joining up with the Islamic State as part of a sort of ‘super-gang’”—enticements including “gamified” recruiting videos from IS.

The channels through which terror and crime affect the West are overwhelmingly homegrown—including a trend of violence targeting these newcomers. Banning the displaced and migrants will have little impact on this challenge—a point underlined by the U.N. What will matter will be better integration of disenfranchised youth and support to narratives from Muslim communities in the West and elsewhere against the ideology of terror. Also worth remembering is that the vast majority of Muslims in the West and beyond are firmly against IS and their ilk, even with the outrages the nativists continue to inflict.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Refugees, migrants, and the politics of fear

April 12, 2017