Wage inequality, according to one popular view, arises from differences in the talent and determination of individuals: Some superstars win, and everyone else does not.

What if the winning superstars aren’t people, however, but companies? Then if you’re working at one of those companies, you’re doing great, and if not — well, good luck.

Consider this: Capital returns at companies are diverging sharply, and the share of them that reap annual returns of more than 25 percent or even 50 percent is growing. This is what Jason Furman, chairman of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, and I found in a study whose results are being released Friday. It’s plausible that some of those big returns are shared with the companies’ employees. And that may well be playing an important role in growing wage inequality.

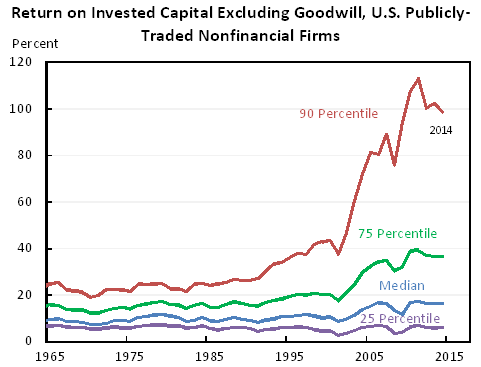

Furman and I present new information, compiled by the McKinsey Corporate Performance Analysis group, on the return on invested capital, which is a more comprehensive measure than the more traditional return on equity. Among the top nonfinancial U.S. companies that are publicly traded, capital return has shown a stunning rise over the past three decades. Excluding goodwill, for example, the 90th percentile of such returns has risen roughly fivefold, from about 20 percent in the mid-1980s to an eye-popping 100 percent in 2014. In other words, the top 10 percent of publicly traded nonfinancial firms earned 20 percent or more on their invested capital in the 1980s, and 100 percent or more in 2014. (The McKinsey data exclude financial companies because of the complexities involved in computing their returns on invested capital.)

Source: Koller et al. (2015); McKinsey & Company

Two features of these high-return companies stand out: They are disproportionately in health care and information technology — from 2010 to 2014, two-thirds were in these sectors. And they are persistent. Among companies that, in 2003, had a return on invested capital in excess of 25 percent, only 15 percent had a return below that threshold in 2013. The vast majority remained in the 25-percent-plus bucket.

All this could help explain why Americans’ earnings are becoming more unequal. Some companies in, say, the technology or financial sectors could generate consistently supernormal returns. Their employees would share the wealth by earning higher wages. Consistent with this possibility, other research suggests that the rise in wage inequality is driven more by a widening gap in the average earnings of workers in different companies than by a widening gap between paychecks inside individual businesses.

Furman and I are tentative about conclusions, because more research is needed to explore these points. But certain things already seem clear. First, in an era in which people are encouraged to be the “CEO of you,” the role of the company nonetheless seems more important than ever. As former Google chief executive officer Eric Schmidt once said to Sheryl Sandberg, now the chief operating officer of Facebook: “If you’re offered a seat on a rocket ship, don’t ask what seat. Just get on.”

And we need to be asking why some companies are earning such high returns on capital. Theoretically, returns of 50 percent or even 100 percent should be short-lived, as they attract competition from other companies. So are the rocket ships just better at what they do, or do they enjoy some unwarranted market power? Policies to address wage inequality may well hinge on the answer.

Editor’s Note: this op-ed originally appeared on Bloomberg View.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edPeople are not unequal; companies are

October 16, 2015