According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the economy added 157,000 jobs during the month of January and an average of 200,000 jobs in the prior three months. These new estimates of job gains now reflect the annual “benchmark” revision to the payroll survey, which showed that the level of employment in December last year was about 650,000 jobs higher than previously reported. As a result, estimates of total job creation in 2012 were increased to 181,000 jobs per month, or a cumulative 2.2 million added jobs over the year. The unemployment rate, at 7.9 percent, has remained at roughly the same level since September of last year.

Thus far in 2013, the major economic focus has been on the budget—the “fiscal cliff” in particular—and the effect of the federal deficit on broader economic activity. Indeed, over the past two years, policymakers have made much progress on reducing the budget deficit. As currently legislated under the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA), the deficit is projected to fall to a more manageable 2.6 percent of GDP in 2018. However, the deficit is projected to rise thereafter, highlighting that, over the longer term, there is still more work to be done in matching revenues and spending.

In this month’s employment analysis, The Hamilton Project explores how the design of budget cuts could impact economic growth and living standards in the coming years and beyond. We also continue to explore the “jobs gap,” or the number of jobs that the U.S. economy needs to create in order to return to pre-recession employment levels.

The Current Path Toward Deficit Reduction

In the past two years policymakers have enacted $3.5 trillion of deficit reduction set to take place over the next 10 years, with $1.1 trillion of these cuts coming from the sequestration scheduled for March 1. Should all these policies go into effect, the ratio of spending cuts to revenue increases would be more than 4-to-1, and the forecasted deficit in 2018 would be about 2.6 percent of GDP, down from 10.1 percent in 2009 and 7.0 percent in 2012. Indeed, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), if most of these policies take effect, policymakers would need to find as little as $257 billion to stabilize the national debt at a sustainable level by the end of the decade [1]. On paper, at least, that suggests policymakers are within reach of resolving the near-term deficit problem.

The problem, however, is that currently scheduled cuts are hugely unpopular with analysts, the public, and most lawmakers. The automatic spending cuts mandated in the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011, are scheduled to begin in March 2013 and end in 2021, evenly divided over the nine-year period. The cuts are split between defense spending (with spending on wars exempt) and non-defense discretionary spending, which does not include entitlements like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. This type of indiscriminate cutting has profound implications for our nation’s economic well being.

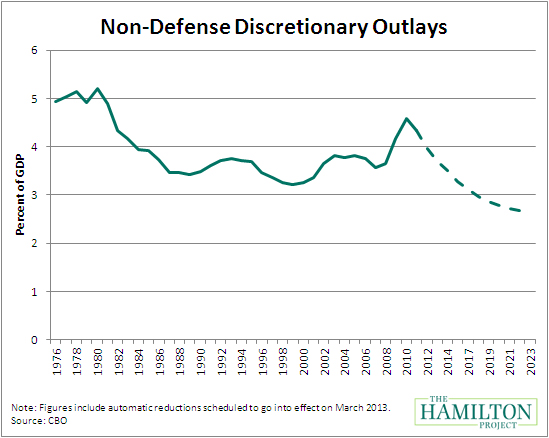

For example, the figure below shows the effects of the recent budget changes, including the sequester, on non-defense discretionary spending. Under scheduled cuts this category of spending would fall to its lowest level in recent history. Why is this a concern?

In today’s increasingly competitive global economy, many Americans have seen their wages stagnate or even decline over the last several decades, and non-defense discretionary spending includes the public investments that, for generations, have helped improve the lives of Americans and provide economic opportunities of the working and middle classes. Reductions in these spending categories mean less funding for the National Science Foundation, less research into new sources of energy, less training and workforce development, and less spending on education through initiatives such as Pell Grants. This funding provides support to our ailing infrastructure, enables research and development to improve health and foster innovation, and increases access to higher education at a time when we have fallen from second to fifteenth in international college completion rates.

The sequester also threatens to impose deep cuts to defense spending. The new caps would cut non-war defense spending from previously planned levels by about 6 percent this year and about 10 percent from 2014 to 2021. These cuts are particularly challenging because of internal pressures within the military budget in areas where costs are projected to rise faster than inflation. Between 2000 and 2010, the Department of Defense expanded its force by 4 percent, but costs increased by more than 40 percent. Much of this cost growth is driven not by increases in capacity or new investments, but by rising costs in areas such as military personnel and operation and maintenance. Left unaddressed, these growing costs will crowd out spending for military readiness and other vital capabilities.

But there are also short-term concerns about the economic effects of the sequester. The U.S. economy is still weak. As we discuss below, the nation faces a massive jobs gap, and private forecasters suggest that the sequester could subtract 0.7 percentage points from economic growth in 2013. In this respect, the sequester runs counter to the textbook economics solution to this situation, which is to enact sustainable budget consolidation today, but to delay its effect until the economy is on sounder footing.

The January Jobs Gap

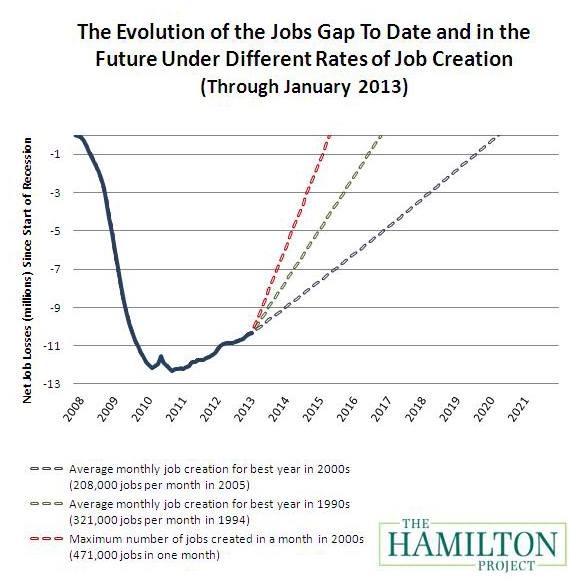

As of January, our nation faces a “jobs gap” of 10.3 million jobs (even after incorporating the effects of this month’s positive revisions to employment growth). The chart below shows how the jobs gap has evolved since the start of the Great Recession in December 2007, and how long it will take to close under different assumptions of job growth. The solid line shows the net number of jobs lost since the Great Recession began. The broken lines track how long it will take to close the jobs gap under alternative assumptions about the rate of job creation going forward.

If the economy adds about 208,000 jobs per month, which was the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 2000s, then it will take until April 2020 to close the jobs gap. Given a more optimistic rate of 321,000 jobs per month, which was the average monthly rate of the best year of job creation in the 1990s, the economy will reach pre-recession employment levels by November 2016. Again, these figures do not reflect the anticipated update to the payroll data due in February, which may reduce the actual jobs gap. You can also try out our interactive jobs gap calculator by clicking here and view the jobs gap chart for each state here.

Conclusion

The spending cuts and revenue increases made in the last two years put the nation on a path toward fiscal sustainability, but the real challenge lies in ensuring that deficit reduction is done in a way that preserves the ability of the government to make much-needed public investments and to tackle our long-run economic challenges. Achieving real fiscal balance will require creative thinking about which areas of the budget can be made more efficient and about which areas should be preserved.

To that end, The Hamilton Project asked experts from a variety of backgrounds—the policy world, academia, and the private sector—and from both sides of the political aisle, to provide innovative, pragmatic proposals for lowering the deficit that take into account impacts to the economy at large. The resulting 15 proposals range across budget groups, and include options to reduce mandatory and discretionary spending, to raise revenues, and to improve economic efficiency. The proposals will be featured this month in a two-part budget series.

The first event, “Budgeting for a Modern Military,” will be held on February 22nd and feature two proposals for reducing defense spending while preserving national security. The authors of the papers—Retired Admiral and former Chief of Naval Operations Gary Roughead, and former CBO Assistant Director Cindy Williams—will be joined to discuss their ideas by high-level experts including former Deputy Secretary of Defense and former CIA Director John Deutch, former Undersecretary for Defense Michele Flournoy, and former Senate Armed Services Chairman Sam Nunn.

The second forum, “Addressing Entitlements, Taxation, and Revenues,” will be held on February 26th and feature a diverse group of authors who will present their proposals, which touch on topics as wide-ranging as immigration, transportation, healthcare, and mortgage interest. These proposals provide options for bringing the budget into balance that, in contrast to the sequester, do not compromise the future well-being of Americans by sharply cutting public investments.

For updates on the event, follow us @hamiltonproj and join the conversation using #RethinktheBudget.

[1] This estimate assumes that the $1.1 trillion sequestration takes effect and the costs of $400 billion of so-called “tax extenders” are paid for, but that scheduled cuts to Medicare physicians (totaling roughly $250 billion) will not take effect and would not be paid for.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Not All Cuts Are Created Equal: Why Smart Deficit Reduction Matters

February 1, 2013