This viewpoint is part of Chapter 6 of Foresight Africa 2026, a report on how Africa can navigate the challenges of 2026 and chart a path toward inclusive, resilient, and self-determined growth. Read the full chapter on leveraging technology, trade, and integration.

While the U.S. market, like the EU, may continue to offer episodic opportunities, the future of African trade lies closer to home.

Introduction1

The announcement of the application of high tariffs on U.S. imports in April 2025 generated a considerable amount of anxiety and concern among policymakers and exporters across the world, especially on the African continent. This alarm was compounded by the widespread perception that the United States remains one of Africa’s main export markets. Several recent studies have indeed been warning of a large-scale reduction in Africa’s exports to the U.S.—with particularly sharp declines in Africa’s clothing exports.2

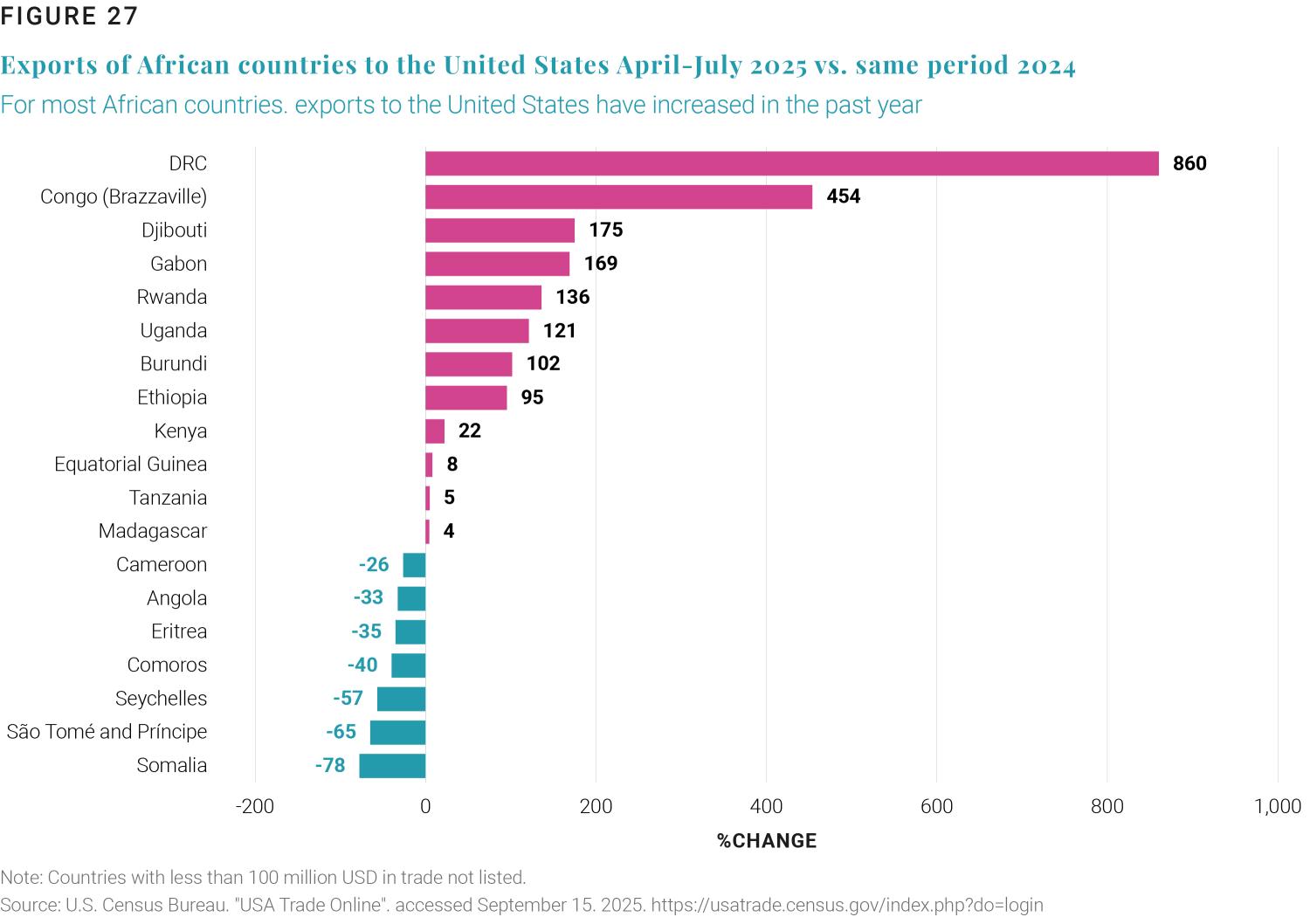

But are these concerns warranted? Judging from recent U.S. import data, the answer is probably no (see Figure 27). For instance, this year, exports from Eastern Africa to the U.S. were up to where they were in 2024. In the case of Kenya—a major clothing exporter in the region—its exports to the U.S. increased 22% between April- July 2025, compared with the same period the previous year, reaching a three-year high.3 Despite having been suspended from the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) in 2022, neighboring Ethiopia experienced an even greater jump in its exports, with a 95% increase.4

It is true that some countries’ exports have fared poorly since the tariff announcements—most notably, South Africa, which in the face of a 30% tariff rate has experienced a drop in exports to the U.S.5 But even for South Africa, while automobile exports have declined, agricultural exports to the U.S. have been strong, rising by 26% in the second quarter of 2025.6 Moreover, not all cases of Africa’s export decline have been related to the tariffs (for instance, in 2025 Angola saw a slump in its oil production, which reduced its export earnings).7 For the continent in aggregate, between April and July, U.S. imports from Africa increased by 6.5% year-on-year, and rose by an impressive 23.9% for the year from January-July.8

What is going on, and why do the initial fears appear misplaced? The first thing to stress is that although the tariffs were announced in April 2025, there was a stay of execution, and tariffs were not actually imposed by the U.S. administration until August. For the 32 sub-Saharan Africa beneficiaries of AGOA, they could also continue to ship goods under AGOA tariff preferences (although this no longer applied after September 30, 2025, when AGOA expired).9

It is entirely possible that the negative impact of the new tariffs has yet to materialize and will emerge later in the year. We cannot discount this scenario (delays to release of U.S. trade statistics, caused by the federal government shutdown, obscure a fuller picture).10 If this is the case, then the rise in Africa’s exports may simply reflect a rush by U.S. importers to stockpile inventory ahead of tariff implementation. But something more significant may be at play, too.

A dramatic shift in global trade

The reality is that U.S. tariffs have affected all and sundry. Some of the world’s leading trading nations have been hit particularly hard—for instance, at the height of the bilateral dispute between China and the U.S., the tariff to be imposed on Chinese imports reached over 140%, though subsequent negotiations brought that down to a trade weighted average of 36%11. As a result of all this uncertainty, Chinese exports to the U.S. were down by over 25% in October compared to 2024.12

The new U.S. tariffs are thus provoking a rapid reorientation in global trade flows as countries try to redirect their exports to other markets, much as economic theory would predict it would.13 And therein lies the principal reason why Africa should not be excessively alarmed: Other regions have had to confront much higher tariffs than those applied on most African exports.

Take again the example of the clothing sector. The leading suppliers of clothing to the U.S. market are China, Bangladesh, and Vietnam—all of which have been hit by much higher tariffs than those imposed on African clothing exporters.14 Those three countries alone supply $45 billion of clothing to the U.S. each year, equivalent to about half of total imports. If you are a U.S. retailer like Walmart, where are you going to source supplies of clothing going forward? Paradoxically, in a situation where the world’s largest importer has applied tariffs indiscriminatingly on its trading partners, some African sectors might end up benefiting from increased orders, as U.S. firms look for alternative sources of supply.

The U.S. will still need the region’s commodities

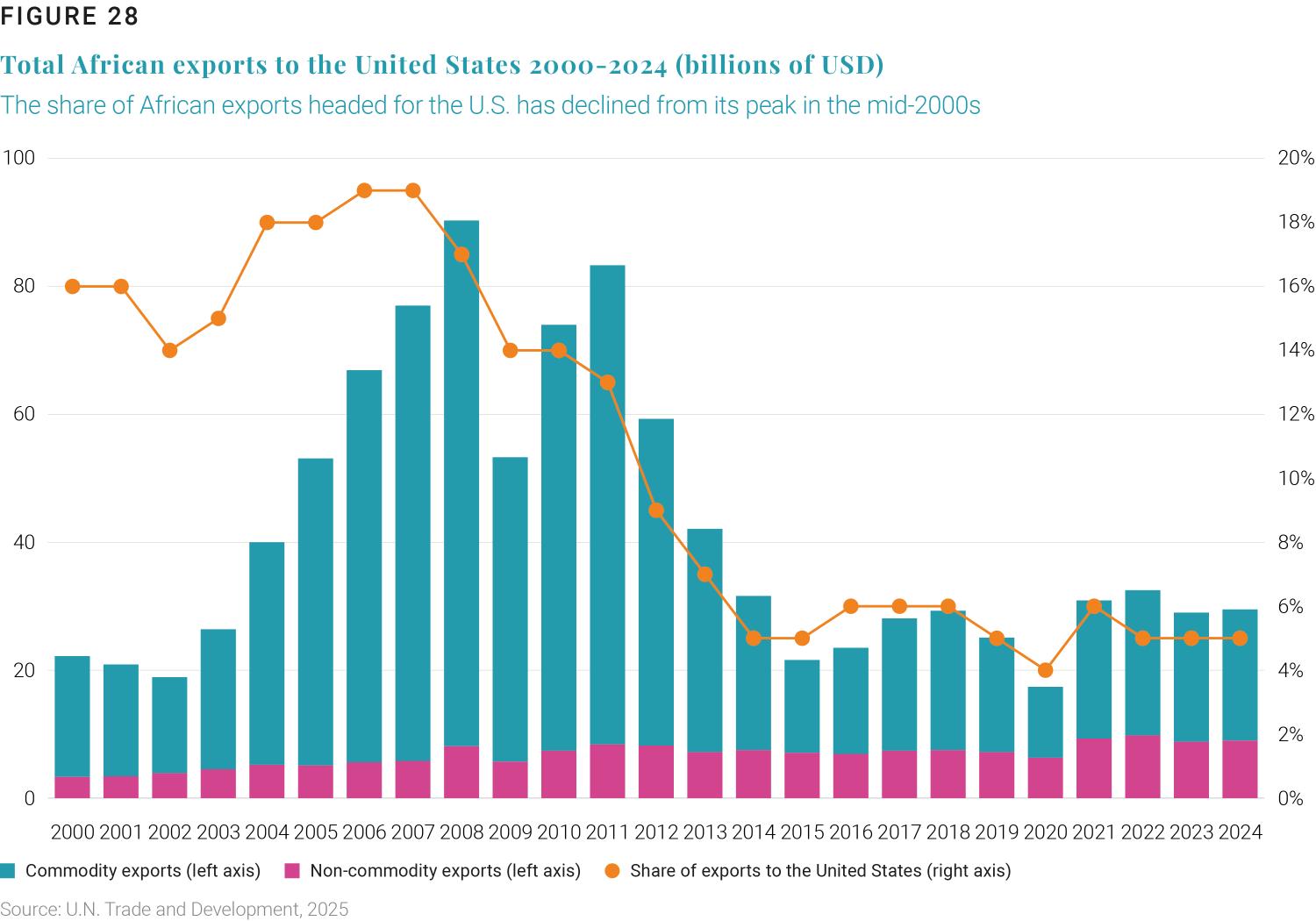

A final factor to consider is that direct exposure to the U.S. market remains limited for most African countries. Despite AGOA having been in place for a quarter of century, the share of African exports headed for the U.S. market has declined from a peak of 19% in 2007 to around 5% today (see Figure 28). Moreover, any export growth that has materialized has tended to be highly concentrated in natural resources. Outside of the clothing sector and a few niche sectors (e.g. South Africa’s automotive components and finished vehicles), existing evidence suggests that AGOA has encouraged little economic diversification of Africa’s exports.15

Against this backdrop, there is an important a priori reason for Africa not to be excessively alarmed by the new tariffs, given that the vast bulk (70%) of U.S. imports from the continent still comprise of raw commodities.16 Since China has started to restrict access to its rare earth metals, the U.S. needs African minerals more than ever. Proof of this is that the largest “winner” from the new American trade policy is the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Its mineral exports have surged since April 2025, rising by a massive 860% compared to the same period last year (Figure 27).17 In another sign of things to come, the American company Energy Fuels plans to invest more than $700 million to exploit a deposit of rare earth metals in the southwest of Madagascar.18 Such demand is only likely to increase over time, as the strategic importance of access to minerals grows.19

What of future trading relations?

None of the aforementioned is intended to downplay the significant adjustment costs that some African economies—e.g., South Africa and Lesotho, which have built export industries around preferential access to the U.S. market20—are likely to face on account of the U.S. tariffs and expiration of AGOA. However, the unpredictability of the tariffs—both in their scope and implementation—should serve as a warning to Africa’s policymakers and business leaders alike. What is granted today can be withdrawn tomorrow, as we have seen in the past with suspensions of countries from AGOA.21 Consequently, few investors are prepared make long-term decisions based solely on current U.S. market access conditions. The risks are simply too high.

The same is unfortunately true for preferential trading arrangements with other trading partners. For instance, despite offering preferential market access to African countries since the Lomé Convention of the 1970s, the European Union (EU) has frequently applied non-tariff barriers on African imports, including strict phytosanitary standards and strong rules of origin requirements.22 More recently, the EU has unilaterally imposed new trading rules related to carbon emissions and deforestation. A consequence has been a gradual decline of the EU as an export destination for the region. In eastern Africa, the EU now accounts for less than 10% of regional exports, compared with around one-third of all exports three decades ago.23

All this suggests the need for a new strategic approach. Africa should double down on regional integration efforts. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) offers a more stable and predictable framework for trade. Reciprocal market access under AfCFTA is binding and intra-African trade is currently the fastest-growing export market for the region.24 By leveraging this momentum, countries can upgrade value chains, reduce exposure to external shocks, and foster their industrial development. In short, while the U.S. market, like the EU, may continue to offer episodic opportunities, the future of African trade lies closer to home.

-

Footnotes

- The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations.

- U.N. Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Tariff Disruptions: The Impact on Least Developed Countries (2025).

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Leading Economic Indicators (2025).

- U.N. Economic Commission for Africa, Eastern Africa Defies Global Trade Headwinds with Resilient Export Growth, September 29, 2025.

- “South African Car Exports to U.S. Plunge as Trump Tariffs Bite,” Reuters, July 14, 2025.

- Yogashen Pillay, “South Africa’s Agricultural Exports to the US Surge despite Looming Tariffs,” Cape Times, August 19, 2025.

- Candido Mendes, “Angola Production Dips below Million-Barrel Level for First Time Post-OPEC,” World Oil, August 21, 2025.

- Computed from trade data available from the United States Census Bureau, downloaded 15th September 2025. It should be noted that the numbers are not currently being updated due to the closure of the federal government between 1st October and 12th November.

- Exports of the AGOA beneficiary countries had actually increased by 26% in the year to August 2025, vis-à-vis the same period in 2024, according to data from the U.S. International Trade Commission (accessed 23rd November 2025).

- Myles McCormick and Ian Hodgson, “US Economic Outlook Obscured by Shutdown-Triggered Data Gap,” Financial Times, November 15, 2025.

- World Trade Organization, “United States of America Imports from China, All Products,” Simple average tariff rate (in percent), WTO-IMF Tariff Tracker, December 1, 2025; Joshua P. Meltzer and Dozie Ezi-Ashi, “Tracking Trump’s Tariffs and Other Trade Actions,” December 2, 2025.

- Joe Cash and Ethan Wang, “China’s Exports Suffer Worst Downturn since Feb as Tariffs Hammer US Demand,” Reuters, November 7, 2025; Anniek Bao, “China’s Exports Unexpectedly Contract in October as Shipments to U.S. Drop 25%,” CNBC, November 6, 2025.

- Sherman Robinson and Karen Thierfelder, “US International Trade Policy: Scenarios of Protectionism and Trade Wars,” Journal of Policy Modeling 46, no. 4 (2024): 723–39.

- Tariffs for China, Bangladesh and Vietnam were initially announced at 35%, 20% and 20%, respectively. See WTO-IMF Tariff Tracker, Accessed December 5, 2025.

- Michael H. Gary and Hugh Grant-Chapman, “What’s Next for AGOA,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, November 6, 2025.

- United Nations Trade and Development Data Hub, “Merchandise Trade Matrix, Annual (Analytical),” UNCTAD Data Hub, October 15, 2025.

- United States Census Bureau, “General Customs Import Value.”

- Emre Sari, “États-Unis – Chine : Le Duel Des Minerais Arrive à Madagascar,” Jeune Afrique, November 14, 2025.

- Ede Ijjasz-Vasquez et al., Leveraging US-Africa Critical Mineral Opportunities: Strategies for Success (Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings, 2025).

- One estimate is 86,000 people have jobs in the South Africa’s auto sector thanks to AGOA, with another 125,000 people employed in related jobs as subcontractors or suppliers. Source: AFP, “Trump Threats to SA Rattle Carmakers as AGOA Decision Nears,” The South African, February 13, 2025.

- Gary and Grant-Chapman, “What’s Next for AGOA.”

- Andrew Mold, Non-Tariff Barriers – Their Prevalence and Relevance for African Countries, No. 25, African Trade Policy Centre (Economic Commission for Africa, 2005).

- United Nations Trade and Development Data Hub, “Merchandise Trade Matrix, Annual (Analytical).”

- U.N. Economic Commission for Africa, Eastern Africa’s Trade Resilience and Regional Integration in Focus at ICSOE 2025, October 3, 2025.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Navigating uncertainty: Africa’s trade prospects with the US

January 28, 2026