In the fields of transportation and land use planning, the public sector has long taken the leading role in the collection, analysis, and dissemination of data. Often, public data sets drawn from traveler diaries, surveys, and supply-side transportation maps were the only way to understand how people move around in the built environment – how they get to work, how they drop kids off at school, where they choose to work out or relax, and so on.

But, change is afoot: today, there are not only new data providers, but also new types of data. Cellphones, GPS trackers, and other navigation devices offer real-time demand-side data. For instance, mobile phone data can point to where distracted driving is a problem and help implement measures to deter such behavior. Insurance data and geo-located police data can guide traffic safety improvements, especially in accident-prone zones. Geotagged photo data can illustrate the use of popular public spaces by locals and tourists alike, enabling greater return on investment from public spaces. Data from exercise apps like Fitbit and Runkeeper can help identify recreational hot spots that attract people and those that don’t.

Simply put, data is better than it has ever been, and public agencies have an incredible opportunity to institute the data-related reforms that will help them deliver more equitable, sustainable, and efficient communities.

However, integrating all this data into how we actually plan and build communities—including the transportation systems that move all of us and our goods—will not be easy. There are several core challenges. Limited staff capacity and restricted budgets in public agencies can slow adoption. Governmental procurement policies are stuck in an analog era. Privacy concerns introduce risk and uncertainty. Private data could be simply unavailable to public consumers. And even if governments could acquire all of the new data and analytics that interest them, their planning and investment models must be updated to fully utilize these new resources.

Using a mix of primary research and expert interviews, this report catalogs emerging data sets related to transportation and land use, and assesses the ease by which they can be integrated into how public agencies manage the built environment. It finds that there is reason for the hype; we have the ability to know more about how humans move around today than at any time in history. But, despite all the obvious opportunities, not addressing core challenges will limit public agencies’ ability to put all that data to use for the collective good.

Emerging Data Sets

The emergence of new data sets is an area of intense opportunity to fundamentally rethink how the country plans, builds, governs, and even finances local transportation networks and the built environment where they operate.

While not intended to be exhaustive, the wide range of sources and the depth of micro-level detail within the data are breathtaking. On the positive side, we have more ways to understand how people move and interact with the built environment than at any point in human history. On the flip side, the data choices and the range of capabilities could be overwhelming.

- There is a distinct shift in who the primary data collector/provider is. Private companies like Google—via its mapping division—now knows more about where people move on a daily basis than their peers in local government who build the roads, rails, and sidewalks that facilitate such travel. Spatial knowledge has diversified.

- There is a distinct shift in the types of data available. Whereas public agencies maintained strong supply-side data—where roads are, the time trains and buses ran—demand-side data was often outdated and expensive to generate. Now, cellphones, GPS trackers, and other navigation devices offer real-time demand-side data. And it’s highly multimodal.

- Many publicly generated data sets are not yet part of public planning processes. The private sector now tracks huge swaths of private citizens’ movements, but the public sector does not always do the same with its vehicles (think service vans or trash trucks) nor do they digitize spatial records like parcel maps. This is a missed opportunity.

- Government programs are playing catch-up to the rate of data innovation. Innovation is simply happening faster outside the public sector. When public agencies are disconnected from the private sector’s innovative geospatial data creation, the exchange of best practices becomes limited.

- Despite the challenges, integrating these new data sets through public-private data sharing can offer clear advantages. By capitalizing on data already being collected by private actors and finding ways to draw insights for public use, agencies can cut costs and improve the automation of data collection and management.

Challenges

While the promise of using emerging data sets in transportation planning is exciting, interviews with key stakeholders revealed clear-cut challenges.

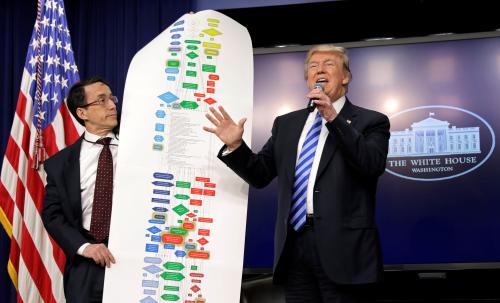

As summarized in the flowchart, those challenges include:

- Lack of governmental capacity and standards. Public agencies simply do not have enough data scientists on staff or senior management experience to navigate a complete transition to big data platforms. The lack of industry-leading hardware capacity and appropriate software—in most places—would similarly restrict their ambitions. The lack of data standards around performance measurement and even data schema further restrict data exchange between public and private actors. And because regulation and capacity is inconsistent from place-to-place, some cities and regions (likely larger ones) will move quicker into the big data era than their peers.

- Procurement is outdated for a big data era. Public agencies typically use what’s known as capital procurement to acquire, inventory, and track physical assets like computing equipment and data. They also tend to go to market with formal ideas in place, meaning requests for proposal leave little room for innovation. Troublingly, this approach extends from the federal government down to local governments. But the big data era includes a shift to subscription services, both in terms of data access and cloud computing. Most innovation also takes places outside government, meaning their requests should leave room for new ideas and to hear from startup firms that may have them.

- The best data is often not yet sharable. While many companies are built to share data—it’s their inherent business model—many are not. As is the case with ride-hailing or telecommunications companies, justifying the enormous risks around privacy concerns and competitive edge for relatively small sales to public agencies might not be worth it. However, the asymmetrical data access will only grow in importance as private transportation service models grow in stature.

- There is risk around calibration, validation, and privacy. Long-established data sets benefit from years of collective calibration and validation: providers continually tweak the methodology, users provide feedback to the data provider, and both enable greater adjustments over time. Think Census products. Emerging data sets don’t necessarily offer the same certainty to public sector users, whether it’s confidence around their longitudinal capabilities or even sample size disclosure. Likewise, standards are not yet in place to protect consumer privacy.

Opportunities

Integrating emerging data sets into transportation and land use policy frameworks will require more than simply procuring data—it will call for major adjustments to internal and interagency processes. Below are some key implications as governments try to modernize their approach to transportation and land use data.

- Hard-wiring objectives into planning processes. Simply acquiring new data sets won’t be enough. To ensure public agencies get value out of their new digital assets and the staff to manage it, they should put those acquisitions to work around specific objectives. Does the region want to reduce its carbon footprint? Is improving job accessibility a top priority? Which industries does the region want to grow and attract? If data can’t speak to such broader objectives—and inform related performance measures—then it runs the risk of becoming a wasted investment.

- Improve public sector capacity. Data science is a relatively fast-growing field, and wage numbers suggest the labor force supply is not keeping up with demand. This puts the onus on the public sector to make a clear value proposition to attract data scientists and to train or recruit managers for related divisions.

- Update procurement policies. First, the public sector will have to update its financial practices to accommodate a subscription-based model within budgeting processes. Second, the public sector will need to make sure it requests the right kinds of data, including metadata, vintage, and future support. Many local and state governments now have chief information or data officers—sometimes centralized, sometimes stationed within multiple agencies—who manage these roles, and enabling them to foster more interagency collaboration will be crucial.

- Consider new systems to centrally manage data. Many interviewees expressed the need for economies of scale. At a small scale, this could mean the federal government buys expensive data sets and makes it available to any public entity. But there is also a larger concept of a new data utility: a centralized place to house sensitive private data—one that is accessible to all public agencies, and where data standards for collection, analysis and sharing can be explored and established.

Conclusion

The combination of millions of geospatial sensors—whether smartphones in individual pockets or fixed equipment in public spaces—and rapidly developing computing capacity have created new opportunities to answer a long-held fascination: how are people and products moving around – in cities, suburbs and rural areas? Emerging data sets based on travel, fitness, and purchasing habits can be combined with geo-located real estate and infrastructure data to enable public agencies to answer this fundamental question with more certainty than at any time in human history. Plotting near-misses on city streets, understanding athletic use of public lands, mapping how many neighborhood residents shop locally: these high-tech inputs are no longer science fiction.

Yet leveraging all this new data will not be easy. Innovations to address privacy and procurement concerns are crucial to successfully integrate emerging data sets into current public policy frameworks. Government capacity, both in terms of staffing and financial resources, will need to improve. Data-rich firms will need to develop comfort sharing data with public agencies.

There is reason for optimism, though. The challenges listed in this report are surmountable, and doing so will help develop new forms of public-private partnerships and modernized policy frameworks along the way.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).