Teens vs. Toddlers: When to Intervene?: First in a four-part series examining the debate over when to intervene to improve social mobility. Read Part 2.

The younger kids are, the less the Federal government spends on them: that’s one message of The First Eight Years: Giving Kids A Foundation for Lifetime Success, published today by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Bad news, given what we know about the critical development during this early childhood period. Experiences in early childhood lay the foundations for cognitive, non-cognitive, and physical development. Early childhood gaps between affluent and poorer children predict and shape lifetime inequalities.

Neurons and Good Night Moon

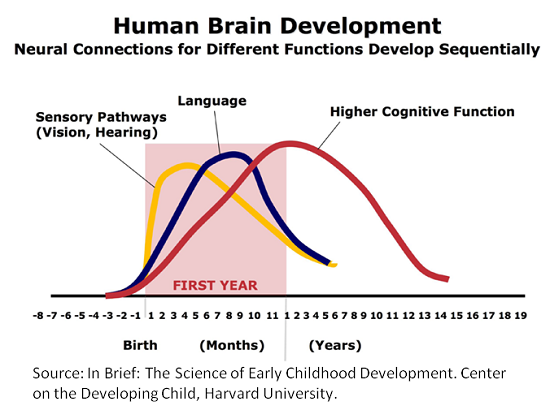

Neuroscientists are showing that the future capabilities of the brain are shaped by experience: neurons that “fire together, wire together.” Early experience is especially important, because the brain is most flexible in the early years—and development is cumulative. Responsive parenting can promote healthy response to stressors. Reading to small children, or even simply talking to them, helps create a stimulating environment, which can create pathways in the brain for future associations:

Early Childhood Gaps = Lifetime Gaps

Variations in early childhood experiences are the first contributing factor to income, education, and race gaps. Fewer than half the children living in poverty at 9 months are school-ready at age 5, compared to 75 percent of children in households with incomes of at least 185% of the poverty line. Established early, these achievement gaps persist through childhood and shape adult outcomes.

Act Early, Get Value for Money

Early childhood interventions are likely to be good value, not least because the costs of policy tend to rise with the age of the child, as Jim Heckman argues. Consider the cost of helping a student develop basic academic and behavioral skills in middle childhood, versus the cost of helping an individual to graduate from college.

Early childhood matters a lot. But that is not to say that it’s game over by the age of five. Tomorrow, we’ll look at the case for devoting resources to intervening in adolescence.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Mobility Begins in Early Childhood

November 4, 2013