“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” With these words Charles Dickens opens his novel “A Tale of Two Cities.” Winners and losers in a “tale of two commodities” may one day look back with similar reflections, as prices of metals and oil have seen some seismic shifts in recent weeks, months, and years.

This blog seeks to explain how supply, demand, and financial market conditions are affecting commodities’ prices in somewhat different ways. Stay tuned for a deeper analysis of the trends in a special commodities feature, which will be included in next month’s World Economic Outlook by the International Monetary Fund.

The effect of low metal prices is likely to have dramatic consequences for metals and oil exporters alike, especially as African countries have made major discoveries in mines and oil/gas in recent decades. For countries like Mozambique, Tanzania, and Uganda, where the investment phase in the extraction sector has started but the production has not, there are especially important macro-fiscal risks.

Metals matter

Base metals—such as iron ore, copper, aluminum, and nickel—are the lifeblood of global industrial production and construction. Shaped by shifts in supply and demand, they are a valuable weathervane of change in the world economy.

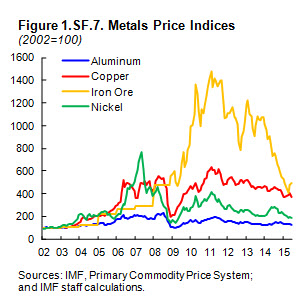

There is no doubt about the direction of the prevailing wind for metals in recent years. Prices have been gradually declining since 2011 (see Figure 1.SF.7). While oil prices have also dropped, their decline is more recent (prices peaked in 2014) and more abrupt. That said, in both cases, the downward pressure on prices result broadly from abundant production from the era of high prices. This is now coming home to roost with lower demand from both emerging markets and advanced economies. There are importance nuances, however, in the relative strength and nature of those forces.

Appetite for production

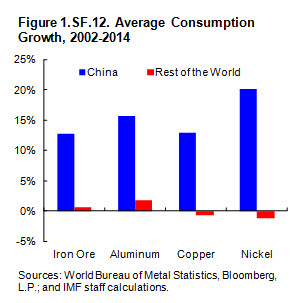

In the early 2000s, demand for metals shifted from advanced economies in the West to emerging markets in the East. China, by far the main driving force, now accounts for half of global base metal consumption. Compare that with China’s more modest consumption of 14 percent of the world’s oil, which is almost exclusively used for transportation.

It is therefore no surprise that metal prices are heavily influenced by demand, and the needs of one economic giant in particular. (India, Russia, and South Korea have also increased their metal consumption, but remain far behind China.) The slower pace of investment in China in the last few years, however, compounded by concerns over future demand amid the sharp stock market decline and currency devaluation this summer, has been exerting downward pressure on metal prices.

Oil supply glut

In our other tale, concerning oil prices, our view is that supply factors are playing a bigger role than demand ones. (See also our blog from last December.) OPEC’s decision to maintain its level of production and strong shale oil production in the United States—in addition to the large production capacity from earlier investment—have contributed to an unprecedented supply glut.

Add to that the prospect of Iran increasing oil production following the nuclear deal; Congress possibly lifting the U.S. ban on crude oil exports; and Libya and Iraq beating many analysts’ expectations for production, despite their difficult geopolitical contexts. With slowing demand from emerging markets and advanced economies, we are more likely to see an era of much lower prices than we have seen in the past few years.

Hooked on metals

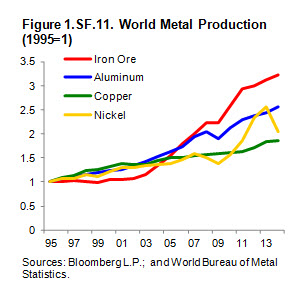

While we have highlighted changes in demand, supply also matters in the metals story. Global production has increased across the board for most metals, owing to rapid investment in capacity in the 2000s. Strikingly, the world production of iron ore has tripled since 2003.

Such resource wealth can be a boon to developing countries, but it can also pose macroeconomic challenges if it accounts for a large portion of their exports. Fluctuations in prices or changing demand from large importers such as China imply obvious vulnerabilities.

Over the last decade, many developing countries have seen their dependence on metals exports deepen. For example, metals account for more than half of the total exports of Mauritania, Chile, and Niger.

Financial market conditions

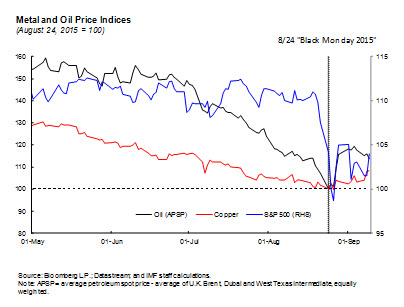

Beyond supply and demand, a third factor has been influencing short-run fluctuations in commodity prices. Investors can rapidly move away from what they perceive to be riskier bets, including stocks and commodities. This so-called “risk off” behavior has at times put downward pressure on prices of both oil and metals. The sell-off on August 24 is a clear example. Initially oil prices recovered, then metals also rebounded significantly.

Metal and oil price indices before and after “Black Monday”, August 24.

The next chapter

Just like a Dickens plot twist, the next moves of metal prices cannot be predicted with certainty. Futures markets clearly point to continued low prices. But it is helpful to go beyond futures and review the forces underpinning demand and supply of metals.

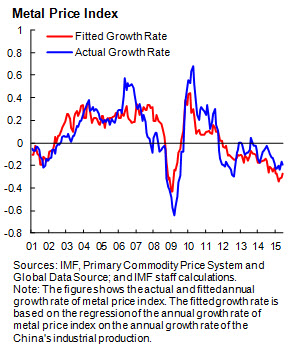

On the demand side, the Chinese economy is projected to slow further, gradually, but with considerable uncertainty. Our simple analysis finds that 60 percent of the variance in metal prices can be explained by fluctuations in China’s industrial production. Recent further falls in Chinese industrial production could further justify metal price declines, especially considering the intended rebalancing that is shifting away from investment toward consumption. The change in the composition in China’s growth may disproportionately affect metals compared to oil for reasons like the decline in the construction sector and the rising demand for transportation from the growing middle class.

On the supply side, investment in the metals sector has dropped but it is unlikely that it will lead to a significant price rebound in the near future. Indeed, low energy prices have helped in reducing costs for mining and refining including for copper, steel, and aluminum.

We also continue to discover more and more major mines outside advanced economies, which will add to global supply. Indeed, the frontiers of metals extraction have been expanding to Latin America and Africa over the past decades, and this trend is unlikely to reverse significantly. If anything, improvements in the investment climate, which drives investment in exploration and extraction, are likely to steadily continue in these regions. Ample supply is therefore likely to continue pushing metal prices further down.

Bottom line

While both oil and metal prices are currently relatively low, there are importance nuances in the underlying driving factors behind the fall. All in all, the imbalance between weaker demand and steady increase in supply suggests that the metals market is likely to see a continued glut and a “low for long” price scenario. If this turns out to be true, there is a risk that investment will continue to falter and lead to a sharp increase in prices down the road.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Metals and oil: A tale of two commodities

September 16, 2015