Below is Chapter 6 of the 2026 Foresight Africa report, which brings together leading scholars and practitioners to illuminate how Africa can navigate the challenges of 2026 and chart a path toward inclusive, resilient, and self-determined growth.

Africa’s regional integration is now an urgent operational priority. With one million young Africans entering the labor force every month,1 no strategy better addresses the continent’s employment challenge than integration. It is Africa’s key to unlock industrialization, scale up productivity, and create quality jobs for the growing youth population.

Sectors where intra-Africa trade is already strong—agro-processing, logistics, light manufacturing, and transport equipment—represent emerging, labor-intensive regional value chains that offer the opportunity for meeting expanding regional demand with local production.2 Integration in these sectors provides a pathway to grow market size; enable firms to scale, formalize, and hire; as well as lower entry barriers for informal traders through inclusive trade corridors.

Yet despite high-level political commitments, Africa’s integration remains fragmented. Only 100 of the African Continental Free Trade Area’s (AfCFTA’s) 4,500 tariff-line products are actively traded under its preferences.3 Meanwhile, global shifts, strategic decoupling, climate-linked trade regulations, and friend-shoring are reshaping global trade dynamics. This essay outlines four interlocking pillars to make integration work: (1) build regional production networks, (2) reduce trade frictions, (3) reboot trade agreements, and (4) deliver regional public goods for lasting impact.

Integration is Africa’s key to unlock industrialization, scale up productivity, and create quality jobs for the growing youth population.

From fragmentation to regional production networks

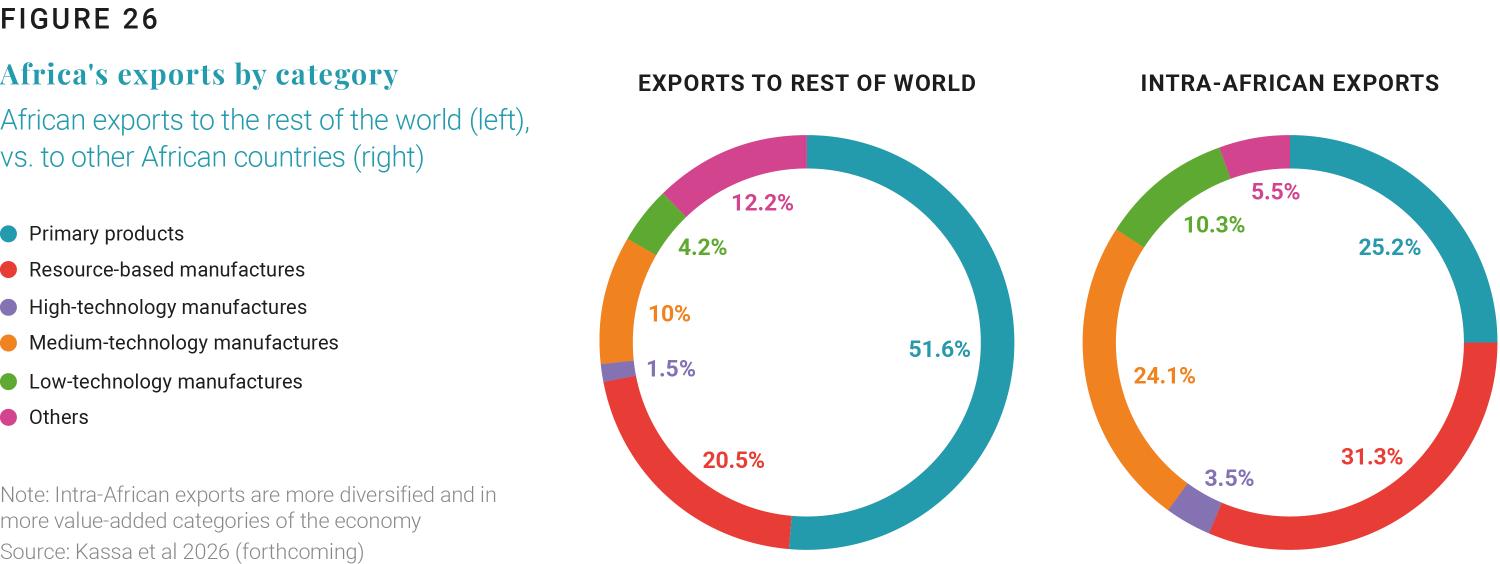

Africa’s trade structure reveals a productivity challenge: exports are dominated by raw materials and low-complexity goods. Participation in global value chains remains limited and is predominantly through forward linkages (i.e. as inputs to other industries), mostly in extractives and raw materials, with minimal domestic processing or learning effects.4 Meanwhile, limited backward integration reflects weak industrial linkages and learning. Without a shift toward capability-based production, the continent risks remaining trapped in low-wage, high-risk commodity dependence.

Regional integration enables export diversification by aggregating scale and capabilities across borders. While individual African countries have limited export opportunity, regional blocks such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) or the Southern African Development Community (SADC) reveal a higher density of feasible sectors. This finding underscores a core insight of an upcoming World Bank report5 on Africa’s integration: Regional markets are not just larger; they are structurally more conducive for industrial upgrading.

Intra-African trade centers on labor-intensive, value-added goods like processed food and light manufacturing (see Figure 25), which have high employment potential but limited global export share. “Small push” sectors (e.g., textiles) can easily scale within the region, while “big push” sectors (e.g., pharmaceuticals) need coordinated investment. Regional specialization, SADC in chemicals, ECOWAS in food, the Arab Maghreb Union in machinery, show that integration can foster complementary value chain hubs rather than competition.

Regional production networks in Africa are still nascent, but early signals are promising. In South Africa, a growing automotive cluster supplies components across the region, bolstered by multinational investment and government incentives.6 The Zambia–DRC Battery Corridor, backed by the World Bank and other MDBs, links mineral reserves with regional processing and EV battery manufacturing.7 Kenya and Tanzania have also begun integrating cross-border agro-processing and packaging industries, aided by EAC regulatory harmonization and corridor upgrades.8 These are early signals of potential, but robust regional value chains (RVCs) will depend on stronger coordination, infrastructure, and policy alignment.

Integration via regional production offers Africa a credible path to large-scale industrialization. Countries must focus not just on what they produce, but how to integrate and grow within regional ecosystems.

Fixing the frictions: Trade costs, corridors, and regulatory hurdles

Within Africa, regional integration remains constrained not by tariffs, which have fallen significantly, but by high and persistent trade costs driven by regulatory fragmentation, infrastructure gaps, and institutional weaknesses.9 Neighboring countries in Africa can be as “economically distant” as countries separated by oceans. This economic separation undermines the potential for RVCs by inflating the cost of moving goods, services, and people across borders.

The sources of these frictions are well known but persist due to a lack of policy coordination and enforcement. Transport markets are fragmented by restrictive bilateral permit systems, inconsistent axle-load rules, and cargo-sharing quotas that deter efficiency and competition. In the ECOWAS region, for example, opaque permitting systems and national trucking quotas limit the emergence of regional logistics markets.10 In the Central Africa corridor between Douala and Ndjamena, clearance times and logistics costs are very high, and the roads remain among the worst in the world.11 Corridors are vital to regional trade but often lack strong governance. Most rely on non-binding MoUs, with no legal authority or funding, making them dependent on political will.

Digitization can be a transformative tool. Digital tools like the Regional Electronic Cargo Tracking System (RECTS) and the Single Customs Territory in East Africa have cut Mombasa– Kigali transit from 21 to 7 days,12 while the Interconnected System for the Management of Goods in Transit (SIGMAT) in West Africa slashed border clearance times.13 However, such systems remain limited in scale, leaving many corridors without digital integration or data-sharing. This inaction disproportionately harms landlocked and smaller economies reliant on efficient trade routes.

To address these frictions, a clear and actionable policy agenda should:

- Harmonize regulatory frameworks across transport, customs, and border procedures either through AfCFTA Phase II protocols or Regional Economic Community (REC)-level agreements.

- Empower corridor authorities with legally binding mandates, operational funding, and enforcement mechanisms to govern multi-country infrastructure and logistics.

- Scale up digital platforms like RECTS, SIGMAT, and electronic single windows to enable real-time cargo tracking, paperless clearance, and regional data-sharing.

- Transition to multilateral transport regimes, replacing bilateral trucking permits with region-wide licensing and competition frameworks.

- Link “hard” infrastructure investments to “soft” reforms by conditioning financing on regulatory harmonization and performance metrics. Addressing these “soft” barriers will make Africa’s hard infrastructure work for trade and transformation.

Rebooting trade agreements for regional growth and transformation

While the AfCFTA is a landmark achievement, its real impact hinges on transforming how African firms trade, invest, and compete, not just on formalities like signatures or tariff reductions. The key challenge is to deepen and enforce Africa’s existing trade agreements, which are currently very shallow compared to other regions.14 Although 90% of goods are tariff-free in principle, critical legal frameworks in services, investment, and intellectual property remain incomplete, and most agreements lack binding commitments and credible enforcement compared to those in Asia or Latin America.15

Furthermore, utilization of trade preferences remains low across Africa, not from lack of interest, but due to complex rules of origin and burdensome documentation that small firms struggle to meet. Services trade faces even greater constraints, with restrictions to licensing, qualification recognition, and professional mobility. Key sectors like logistics, finance, and digital trade are also fragmented by regulatory barriers, limiting scale and integration. Despite growth in digital services, few countries support cross-border data flows or digital contract recognition. Deeper integration could boost intra-African trade by up to 109%, versus just 16% under shallow agreements.16

A rebooted trade architecture should:

- Simplify and harmonize rules of origin across RECs and the AfCFTA. Adopt flexible rules, enable self-certification, and provide capacity support for firms to comply.

- Deepen services liberalization, especially in transport, logistics, digital trade, and professional services, focusing on regulatory convergence, not just tariff schedules.

- Strengthen dispute resolution and enforcement. Trade agreements need credible mechanisms to resolve conflicts, ensure compliance, and build trust among firms and states.

- Make existing agreements work for firms. Embed firm-facing mechanisms, such as one-stop desks, online portals, and customs interoperability, into AfCFTA implementation.

- Use the RECs and AfCFTA Secretariat strategically. Go beyond negotiations to support implementation, monitor performance, and build capacity that ensures real economic outcomes.

With this architecture, agreements become tools for real economic integration, empowering firms to scale across borders and transforming treaties from symbolic commitments into engines of continental growth.

Delivering regional public goods: The missing lever

Regional integration cannot thrive on trade and markets alone—the provision of regional public goods (RPGs): infrastructure, energy systems, peace and security, and data governance, is necessary. These goods are the connective tissue of integration: lowering trade costs, enabling scale, and de-risking cross border investment. Yet Africa chronically underinvests in them. Consider energy: 17 countries in Africa rely on electricity imports, but regional power pools remain underutilized due to weak regional governance and financing bottlenecks. Security follows a similar pattern: Regional spillovers from conflict (e.g., Sudan, eastern DRC) continue to disrupt trade and mobility, yet regional enforcement remains weak. The African Union’s Peace Fund is underfunded and its mandates often lack binding authority, limiting its ability to respond decisively.

Integration via regional production offers Africa a credible path to large-scale industrialization.

Africa’s institutional architecture—the African Union (AU), RECs, and emerging plurilateral coalitions—must evolve from coordination to delivery. This means: (i) giving the AU and RECs enforcement authority in RPG domains, (ii) empowering anchor countries to lead, and (iii) creating scalable platforms for project preparation and pooled financing. RECs and the AfCFTA can serve as a delivery platform for RPGs through corridor governance, customs harmonization, and shared standards. But this requires a paradigm shift: Integration is not just about tariffs and trade, but about collective action, where no country can succeed alone. RPGs are not side issues; they are prerequisites for a functional single market.

Conclusion: From agreement to implementation

Africa’s regional integration efforts stand at a pivotal moment. The AfCFTA has established the legal and institutional groundwork, but implementation remains thin, fragmented, and overly focused on tariffs. To deliver jobs, resilience, and structural change, the agenda must now pivot to functionality and implementation. This means building regional production networks by aligning industrial policy with existing demand and potential production capabilities. It means removing regulatory and logistical frictions that raise trade costs even where formal barriers like tariffs are low. It means deepening trade agreements, making them enforceable and linked to investment, services, and digital governance. And it means turning regional public goods— energy, infrastructure, peace, and data—from aspirational into operational realities. Functional integration is more than just a trade agenda, it is Africa’s primary strategy for jobs, resilience, and long-term growth.

Related viewpoints

-

Footnotes

- Declan Walsh, “The World Is Becoming More African,” The New York Times, November 13, 2023.

- Signé, Landry, and Chido Munyati, AfCFTA: A new era for global business and investment in Africa, World Economic Forum, 2023.

- “Tracking Africa’s Progress on AfCFTA,” UNECA, March 20, 2023.

- Albert G. Zeufack et al., Africa’s Pulse, No. 25, April 2022 (The World Bank, 2022).

- Woubet Kassa et al., Integrating Africa: From Threads to Hubs (World Bank Group, 2026), Forthcoming.

- U.N. Economic Commission for Africa, ECA Support Namibia and Lesotho to Review an Automotive Policy Framework to Integrate into the Regional Value Chain, April 8, 2025.

- Silas Olan’g and Thomas Scurfield, “The DRC-Zambia Battery Plant: Key Considerations for Governments in 2024,” National Resource Governance Institute, December 20, 2023.

- East African Community, EAC Vision 2050: Regional Vision for Socio-Economic Transformation and Development (2016).

- United Nations Trade and Development, 2024 Economic Development in Africa Report: Unlocking Africa’s Trade Potential: Boosting Regional Markets and Reducing Risks (United Nations, 2025).

- Olivier Hartman and Niina Kaori, “Transport and the AfCFTA: Road Services as the Missing Link,” Africa Transport Policy Program, August 28, 2025.

- Alexandre Larouche-Maltais, “Why Is the Transit of Goods so Expensive in Central Africa?,” UNCTAD, June 7, 2022.

- “Single Customs Territory,” East African Community, https://www.eac.int/customs/single-customs-territory.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, The SIGMAT System The ASYCUDA Journey in West Africa: Facilitating Cross-Border Transit Trade, INF/2022/1 (UNCTAD, 2022).

- Ngwu, Franklin, and Kalu Ojah. “Intra-Africa trade and the need to rethink the neo-liberal approach.” Transnational Corporations Review 16, no. 4 (2024): 200090.

- Kassa et al., Integrating Africa: From Threads to Hubs.

- Kassa et al., Integrating Africa: From Threads to Hubs.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).