This analysis is part of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy, which is a partnership between Economic Studies at Brookings and the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national health care debate with rigorous, evidence-based analysis leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings.

Executive Summary

Tens of millions of Americans are expected to lose their job-based health insurance amid the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated increase in unemployment. Most people in this group are eligible for coverage through Medicaid or through subsidized coverage in the individual market, but historically take-up of new coverage among those exiting employer-based insurance – particularly those eligible for the individual market – has been quite low. This paper uses survey data to examine how many people exiting employer coverage become uninsured in normal times, and how the share that become uninsured has changed since implementation of the Affordable Care Act. We also make a series of policy recommendations to better support enrollment into Medicaid or Marketplace coverage after a loss of job-based insurance.

Specifically, using the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component, we find that:

- On average, 452,000 people per month left employer coverage for a spell of uninsurance lasting at least 3 months over the period from January 2016 to July 2017, comprising 54% of the total number of people who exited employer coverage during that time period.

- The share of people who exit employer coverage who become uninsured for 3 months or more was 25% higher prior to implementation of the Affordable Care Act.

These data suggest that the Affordable Care Act reduced the risk that losing job-based coverage would result in becoming uninsured, but also demonstrate that important opportunities remain to increase coverage by targeting people who have recently lost job-based insurance. While not everyone who loses employer-based coverage qualifies for or receives unemployment insurance (UI), state UI agencies serve a population that is disproportionately likely to be recently uninsured. To help this group connect to coverage, UI programs can take steps to make coverage enrollment more automatic. States’ options, ranging from least to most resource intensive, include:

- Providing general enrollment related information within the UI application and at periodic UI recertification.

- Providing personalized and interactive information regarding likely eligibility at application and recertification.

- Partnering with nonprofit insurance assisters, other state agencies, or web-brokers to refer UI consumers for enrollment support.

- Building an integrated UI and health coverage application in partnership with a state-based Marketplace or web-broker.

States should consider what steps they can take now, and what investments they can make over the medium-term, especially in the context of other improvements to UI technology. In addition, federal policymakers and those administering state-based Health Insurance Marketplaces have options to make enrollment easier for those exiting employer coverage. They can eliminate burdensome and unnecessary verification requirements, broaden eligibility for Special Enrollment Periods (SEPs), and consider making financial assistance more predictable for this group.

The full report appears below. For a PDF version of the report, click here.

Introduction

COVID-19 and accompanying physical distancing measures have caused unprecedented job losses. More than 20 million people have lost their jobs, and the unemployment rate is now approaching 15%, the highest rate since the Great Depression. Amid this job loss, tens of millions of people are expected to lose their employer-based health insurance. Researchers at the Urban Institute estimate that if unemployment reaches 20%, 25 to 43 million people will lose job-based health coverage and 7 to 12 million will become uninsured, though the actual number of uninsured may be higher.1

This increase in uninsurance is harmful to both those who lose coverage and to the health care system, yet is unnecessary. Since enactment of the Affordable Care Act, most people who lose coverage during an employment transition are eligible for subsidized coverage in the individual market or through Medicaid. Yet this group has historically been unlikely to actually enroll in ACA coverage. Researchers examining coverage transitions in the first year after the ACA’s reforms went into effect found no significant impact on the likelihood of an individual becoming uninsured after employer coverage, even as uninsurance across other groups declined precipitously. Moreover, available data suggest very low initial uptake of coverage among those exiting employer coverage and eligible for an individual market plan. Those losing job-based insurance outside of the 6 week annual open enrollment period each fall must use a Special Enrollment Period (SEP) to enroll in coverage mid-year. Yet based on 2015 data, researchers estimate that only 5% of those eligible for mid-year enrollment were enrolled, though significant uncertainty surrounds their estimates.2

This paper lays out strategies to address this gap and help more people who lose employer-based coverage to successfully transition to Medicaid or the individual market. We begin by using survey data to quantify how many people transition from employer coverage into uninsurance. To reach this group, we recommend state unemployment insurance agencies pursue a series of strategies to promote coverage, ranging from providing health insurance information within their workflows to building a fully integrated application. Finally, we consider federal and Marketplace policies that could help improve coverage take-up among those exiting employer insurance.

How Many People Leaving Job-Based Coverage Become Uninsured?

The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey-Household Component (MEPS-HC) is a nationally representative longitudinal survey conducted in two-year waves, with a new wave beginning each calendar year. Each MEPS-HC Longitudinal Data File reports coverage status and coverage type for individuals in 24 consecutive months.

We analyzed MEPS data from July 2010 to June 2017 and tallied the number of people who experienced two types of transitions:

- Single-month transitions: We examined people who had employer coverage in one month and were uninsured in the next month. This represents everyone who experienced a transition out of employer coverage and into uninsurance, however briefly. In our results, we express this as a level and as a share of all individuals who had employer coverage in one month and did not have it in the next.

- Three-month transitions: We examined people who had employer coverage in one month, followed by three consecutive months of uninsurance. This is intended to capture those who experience a stable spell of uninsurance. As above, we express this as a level and as a share of all individuals who had employer coverage for a month followed by three consecutive months without employer coverage.

We restricted the analysis to individuals under 65 at the end of the first survey year for whom data was collected for all five rounds of interviews covering the two full calendar years. Employer coverage was defined as having health insurance coverage from an employer or union or from TRICARE/CHAMPVA. Uninsurance was defined as having no public or private health insurance. We calculated point estimates and standard errors that account for the survey’s complex sample design based on the guidelines in the MEPS-HC documentation. Results are calculated monthly, drawn from the middle 12 months of each MEPS-HC survey wave (July of year one through June of year two).

Results

In general, this analysis reveals that while there are signs of improvement since 2014 in both the number of and rate at which people who leave employer coverage become uninsured, many people still fail to obtain other coverage after leaving employer-based insurance.

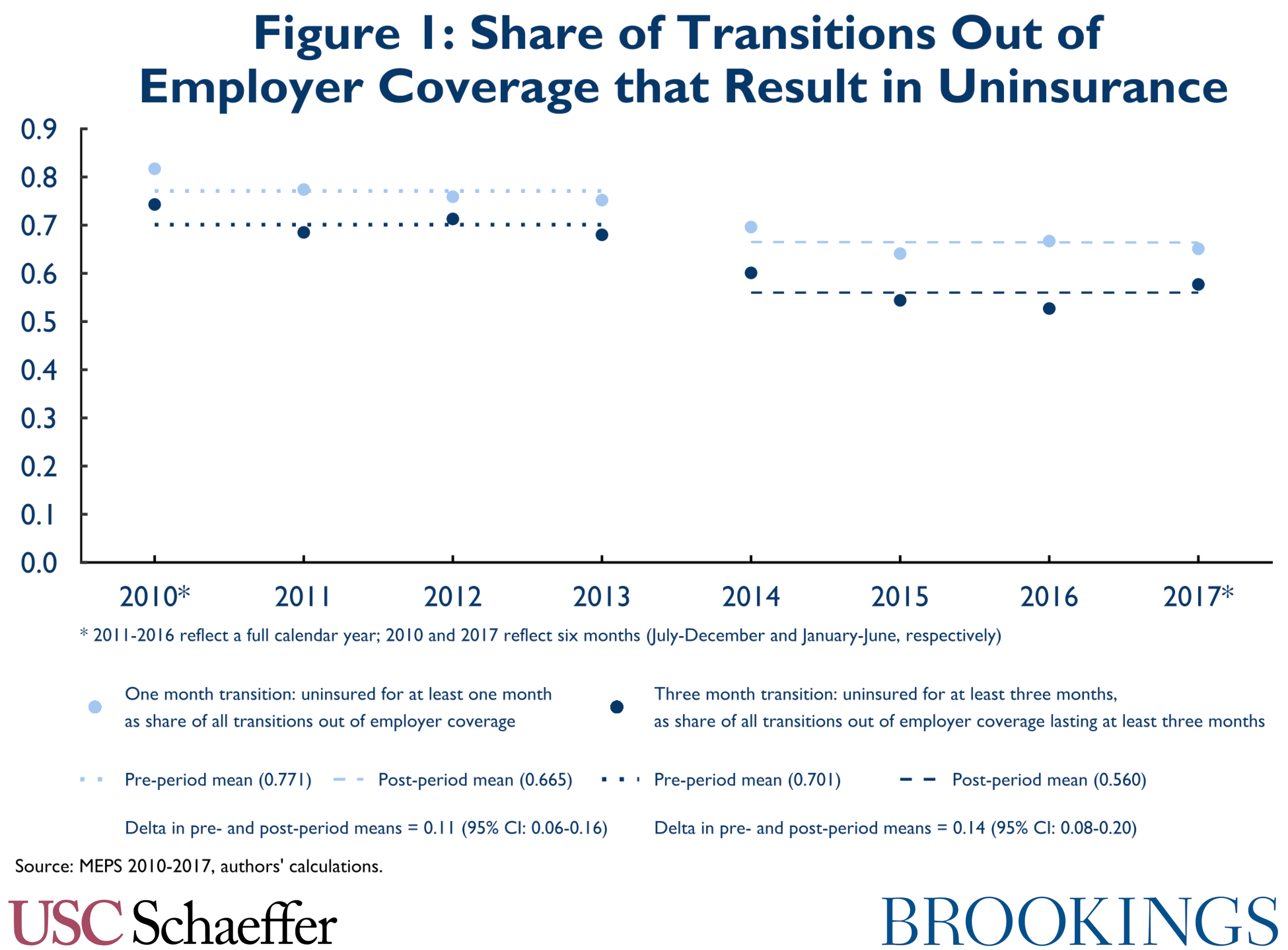

Figure 1 depicts the share of transitions out of employer coverage that result in uninsurance before and after implementation of the ACA’s core coverage provisions in January 2014. (Note that this is not intended to represent the share of people losing their job who become uninsured; it includes all coverage transitions without regard to changes in employment status.) The figure displays transitions lasting at least one month and transitions lasting at least three months. As shown, point estimates indicate that implementation of the ACA was associated with an 11 percentage point decrease in the share of people leaving employer coverage who become uninsured for at least one month (to 67%), and a 14 percentage point decrease in the share of people leaving employer coverage who become uninsured for at least three months (to 56%). These estimates are statistically significantly different from zero, albeit subject to some uncertainty.3

Regardless of improvement we may have seen since 2014, these data reveal that the number of people exiting employer coverage into uninsurance remains large. Figure 2 illustrates the number of people per month that leave employer coverage for uninsurance. In the 18 months from January 2016 through June 2017, an average of 452,000 people per month became uninsured for at least three consecutive months after having had employer coverage in the preceding month. An average of 673,000 people per month experienced at least one month of uninsurance after having had employer coverage in the preceding month.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this analysis. First, there may be inaccuracies with the MEPS reported coverage type. For example, one validation study noted that MEPS respondents underreport insurance coverage; the authors estimated that around 10% of those that indicate they are uninsured actually have private insurance. This may lead us to overstate the number of people who leave employer coverage and become uninsured, although if the reporting errors remain constant over time, the impact of errors on our estimates of trends is likely to be small. Second, panel surveys like MEPS can suffer from “seam bias” in which people report different coverage status in successive interviews even if their true coverage status did not change. The direction of any bias in our estimates attributable to seam bias is uncertain. Lastly, the denominator of our estimate — the number of all transitions out of employer coverage — includes people who voluntarily leave employer coverage for other coverage like Medicare or Medicaid. An increase in these transitions will skew the share of people leaving coverage to uninsurance downward. However, we also see a downward trend in the number of transitions to uninsurance (the numerator of our result) suggesting this will not cause huge distortions in our estimates.

The Unemployment Insurance System Can Promote More Automatic Enrollment

The data above reveal more can be done to support enrollment into coverage as individuals exit employer-based coverage: nationwide, more than 450,000 people each month transition from employer coverage to being uninsured. Targeted efforts to enroll people exiting employer-based coverage in Medicaid or individual market coverage would expand insurance coverage, benefiting the enrollees themselves and the individual market risk pool, while reducing uncompensated care. Leveraging state unemployment insurance (UI) systems to promote a simpler and more automatic enrollment experience could promote these objectives.

To be certain, not everyone leaving employer coverage will interact with their state UI agency. Unemployment insurance is generally only available to unemployed workers who meet certain thresholds for employment duration and earnings, leave a job involuntarily and not for cause, and meet other criteria. (COVID-19-related policy changes have temporarily broadened the pool of individuals eligible for UI.) But people can exit employer-based coverage into uninsurance after a voluntary separation from an employer, after changing to a new job, or because their current employer’s coverage becomes too expensive. Nonetheless, there is significant overlap between ACA coverage eligibility and potential eligibility for unemployment insurance benefits.

The UI System

Unemployment insurance is a state-run program, financed by taxes on employers and operating within federal standards. Workers who have sufficient prior earnings and who are unemployed through no fault of their own are generally eligible for up to 6 months of cash benefits (more during recessions); payment amounts vary by state but on average replace about half of pre-unemployment income. Congress has added additional more generous federally-funded benefits associated with COVID-19. In 2018, 1.8 million workers received UI benefits, and amid the COVID-19 crisis more than 20 million people are currently receiving UI.

Historically, take-up of UI benefits among eligible workers has been higher than take-up of health coverage programs. A variety of estimates suggest that, in recent years, about three quarters of those eligible for UI enroll. Note, though, that those enrolled in UI encompass less than one third of the unemployed. This reflects the fact that many unemployed people are ineligible, either because they left employment voluntarily, have exhausted their benefits or, more commonly, because they earned too little in the prior time period to qualify.

UI generally serves households with incomes above the poverty line. For example, at the peak of the Great Recession, only 14% of families receiving UI in 2009 had annual income for 2009 below the poverty level; 19% had annual income between 100% and 200% percent of poverty, and 67% of households had annual income more than double the poverty level. Through 2018, middle and higher income workers are about twice as likely to receive UI benefits as the lowest-wage households.

To receive UI benefits, individuals generally apply online through a state website, with telephone and in-person applications also available. State UI agencies take some time to process applications – typically 2-3 weeks prior to the COVID-19 crisis. After eligibility is determined, benefits are paid weekly or biweekly. However, beneficiaries must visit the UI website every week or every two weeks to “recertify” their eligibility for benefits – confirming that they remain willing and able to work and are not yet employed. Those who do not recertify do not continue to receive benefits.

Health Coverage Opportunities

This framework presents an important opportunity to encourage enrollment into health coverage. First, there appears to be significant eligibility overlap between the two programs. As noted above, most UI recipients have incomes that would make them eligible for Marketplace coverage, and some have incomes in the Medicaid range (though it is unclear the extent to which the income distribution of uninsured UI recipients parallels the income distribution of the program as a whole). And, of course, this is a population that is disproportionately likely to have recently become uninsured.

Equally significant, the process of applying for and receiving UI lends itself to efforts to facilitate health coverage enrollment. People generally obtain UI benefits by submitting an online application that is similar to the type of online application used for Marketplace and Medicaid coverage, so consumers are already accustomed to the process and have assembled relevant information. In addition, UI beneficiaries interact with the online UI system several times per month to recertify their eligibility, creating multiple opportunities to encourage health care enrollment. Finally, much of the information needed to apply for health coverage overlaps with information provided on the UI application, creating potential opportunities to streamline enrollment.

Options for State UI Agencies

States have a number of options to support enrollment into health insurance among those applying for and receiving UI benefits. Ranging from least to most resource intensive, states can:

- Provide general enrollment related information within the UI application and at recertification.

- Provide personalized and interactive information regarding likely eligibility in the application and recertification process.

- Partner with nonprofit insurance assisters, other state agencies, or web-brokers, and refer consumers for enrollment support.

- Build an integrated UI and health coverage application in partnership with a state-based Marketplace or web-broker.

All of these pathways would create a simpler and more automatic enrollment experience, with individuals able to move more easily from the UI process to a health coverage application. They would not represent truly automatic enrollment – though some variations of the integrated application could approach automaticity. Each of these options is described in more detail below, followed by a brief discussion of the timeline for action.

Provide Basic Information within the Application and Certification Process

With minimal investment of effort, UI agencies can provide information about health coverage enrollment to UI recipients as they are applying and recertifying their eligibility for benefits. Today, 33 state UI agencies have information somewhere on their public-facing websites about enrollment into coverage, but individuals may need to seek out that information by searching the website or actively looking for health care information. However, health coverage may not be front of mind for people experiencing a job loss, and many may simply not consider the issue.

A better approach would ensure that UI applicants and beneficiaries encounter information about health coverage within the consumer’s online workflow as they are applying and recertifying their benefits. The specifics will depend on the structure of the state’s application and recertification processes, but in general UI agencies can present a screen that contains health coverage information within the application and recertification submission. For example, after moving through each page of the application, individuals can encounter a screen that provides a few sentences of information on health coverage eligibility, and the customer must click somewhere on the screen to continue. Moreover, in addition to offering this information at the time of an initial applications, UI agencies have a valuable opportunity to present it on an ongoing basis during weekly or biweekly recertifications. The UI recertification process is generally less complex than the initial application, so individuals may be more interested in the material in future weeks, and the ongoing interaction will reinforce the opportunity to obtain coverage. Anecdotally, it appears some UI agencies have taken this approach, but it is not widespread.

The information presented in this context should be simple, and should be focused on driving consumers to apply for coverage through Medicaid or the Marketplace. Marketing experts have emphasized two kinds of messages that can be effective in motivating action to seek coverage – information related to affordability and related to deadlines. Consumer awareness of affordability is limited. A 2019 survey of uninsured consumers likely to qualify for Marketplace subsidies found only 12% were aware that subsidies existed, and they expected coverage to be more expensive than they were likely to encounter. Indeed, 83% thought a plan costing less than $100 per month would be affordable to them but only 46% expected such a plan to be available, when in fact nearly all in the sample would have that option. Further, given low awareness of other aspects of Marketplace operations like the timing of the open enrollment window each fall, there is no reason to expect UI applicants to have any familiarity with the fact that they may have only a 60 day window to enroll in coverage. Therefore, simple messaging in the UI workflow that conveys low cost options are available and that the time to enroll is limited, combined with direct links to the Marketplace website, may be salient in encouraging enrollment, especially if repeated throughout the recertification process.

Note that presenting consumers with this type of information requires limited technical investment from the UI agencies. It does not require the state to add new questions to its application or reconfigure the application; states can add this information within their existing structures. Moreover, state health agencies generally have the necessary expertise to craft messages to consumers. Certainly, some resources are necessary, but it should be possible to provide this kind of information outside of a major technical undertaking.

Provide Personalized and Interactive Information

With a somewhat more significant investment of resources, UI agencies can build on the model described above to offer a more personalized and interactive experience within the consumer’s workflow. Indeed, a randomized controlled trial from the Department of the Treasury suggests that a personalized message provided by the Internal Revenue Service based on prior tax data was effective in encouraging enrollment (and reducing mortality), so a more personalized experience may promote coverage uptake.

For example, at the time of initial application, UI applicants could be asked if they are uninsured or losing health care coverage associated with their job loss, and, if so, as of what date. That information could be used to provide a more targeted message related to the opportunity for coverage and the deadline by which the individual must apply for coverage in the individual market, and this individualized deadline may be more effective in motivating action. Individuals who reported being uninsured or losing coverage could also be asked at recertification if they had obtained or investigated coverage; being asked to interact with the message by answering a question may be more effective in promoting action over time.

In addition, a personalized message related to affordability could also help overcome consumers’ skepticism or lack of awareness about the cost of coverage, as described above. The UI agency possesses data regarding the wages an individual earned prior to becoming unemployed and the amount of their weekly UI benefit, and may have access to prior-year tax data about their family size. This is insufficient information to perform a true eligibility determination, but it could be used in combination with some straightforward assumptions to generate an estimate of the cost of coverage for similarly situated individuals. These estimates could be generated at the person-level or across bands of pre-UI income, and presented to the individual within the application and during recertification. Even while being careful to note the limits of the information, estimates like these could help concretize coverage affordability, driving enrollment.

Referral Partnerships with Assisters, Web-Brokers, or State Agencies

Ensuring that consumers are presented with health coverage information within the workflow, and taking steps to make that information as personalized and interactive as feasible, could meaningfully support uptake of coverage. However, it does not directly address another barrier to enrollment: the availability of consumer assistance. Strategic partnerships between UI agencies and other entities can support that need.

Evidence from the implementation of the Health Coverage Tax Credit (HCTC) in the mid-2000s, which subsidized enrollment into available coverage options for workers losing their job-based coverage, suggests that personalized assistance can have a large impact on take-up rates. States and regions with high take-up rates generally relied on union, other non-profit, or state and local government programs to provide intensive outreach and enrollment assistance at the time of job-loss. Indeed, these experiences reflect that steps that reduce the time and, perhaps more importantly, mental bandwidth necessary to enroll in coverage can be effective – particularly at a time when families are stressed by the disruption associated with having lost a job.

Since implementation of the ACA, coverage assistance has been available to those attempting to enroll, and traditional non-profit and government assisters have been supplemented by an expanding role for insurance agents and brokers, who are paid commissions or otherwise reimbursed by insurance companies for providing enrollment assistance. Publicly available data are limited, but assistance from assisters, agents, and brokers appears to play a numerically significant role in enrollment. For 2018, the federal government reported that 42% of enrollments through HealthCare.gov were connected with one of more than 40,000 agents and brokers, and in 2016 5,000 assister programs estimated they worked with more than 5 million consumers (across both Medicaid and Marketplace coverage).

In addition, in recent years, HealthCare.gov and some state-based Marketplaces have supported a relatively new type of broker-led enrollment through “direct enrollment.” Under direct enrollment, entities called web-brokers operate their own online portals for applying for coverage in the Marketplace, and generally receive insurance company commissions for those who enroll through their sites. Web-brokers may partner with individual insurance agents or brokers who use their technology to work directly with individual consumers. Direct enrollment can also be operated by insurance companies. Available data suggest that for 2020, almost 30% of HealthCare.gov enrollment came through this channel. To be sure, significant concerns have emerged about the web-broker and direct enrollment model. Web-brokers may promote enrollment in non-ACA-compliant coverage, may steer individuals towards plans that pay higher commissions, and may do a poor job helping Medicaid-eligible consumers understand their eligibility and enroll. However, enhanced oversight and tighter standards may help ameliorate some of these problems.

In this landscape, UI agencies have opportunities to partner with assisters or brokers to refer UI applicants and beneficiaries for assistance in enrolling in coverage, which has the potential to meaningfully increase the rate at which individuals successfully enroll. Building on the type of model used successfully to support HCTC enrollment, UI agencies could contract with a non-profit assister to provide enrollment support. Using the type of interactive workflow described above, UI applicants and beneficiaries who reported being uninsured or losing coverage could be asked to consent to having their information shared with a health insurance assister.4 The assister would be provided contact information for those who agreed, and would work with the individual to help them understand their eligibility and apply for coverage. Assisters could contact consumers directly to help ensure completion; presumably, those consenting to have their information shared are expressing at least some interest in obtaining health coverage, making this is a reasonably well targeted population for this type of intensive outreach. Assisters could also provide post-enrollment assistance related to eligibility verification or other issues.

Rather than using external assisters, the UI agency may also wish to enter into referral arrangements with the state Medicaid agency or state-based Marketplace for these outreach efforts, in a manner similar to the Maryland “Easy Enrollment” program. In Maryland, uninsured tax filers are asked to consent to having their tax return information provided to the Medicaid agency and Marketplace and treated as an application for coverage; the UI application could be handled in the same way.

Operating a model like this will require a source of funding, though it may be within reach for states, especially states that operate state-based Marketplaces. State Marketplaces use the revenue collected from user fees levied on insurance companies to support a variety of outreach efforts. Today, resources are generally focused on enrollment during the fall open enrollment period; however, given the opportunity to target support to those who have indicated they are likely to be eligible for a special enrollment period and the very low take-up that exists today, partnerships between UI agencies and assisters could prove to be a cost-effective model. Of course, the federally-facilitated Marketplace may also consider using its own user fee supported outreach resources to support partnerships between UI agencies and assisters in its states.

Alternatively, partnerships between UI agencies and web-brokers have the potential to offer some of these benefits without requiring the same funding commitment, though close supervision will be necessary. As above, for consumers that appear potentially eligible for coverage, the UI agency could ask for consent to share information with a partner web-broker, who would then help support the individual’s enrollment. One could imagine a state UI agency operationalizing this model through a state procurement process. The state would issue a request for proposals (RFP), inviting submissions from web-broker entities that could meet strict standards established by the state. Those standards should include a commitment to accurately assess Medicaid eligibility and support Medicaid enrollment alongside private insurance enrollment, displaying all private insurance options on equal footing without regard to commissions, strict limits on the use of consumer information, and regular oversight. Respondents to the RFP would explain how they would meet the standards and offer specific service-level commitments related to the amount of consumer outreach and post-enrollment assistance they would conduct; the state would select one or multiple web-broker partners based on their responses.

Partnering with a web-broker would require some state resources to conduct the necessary oversight and build the interactive application that would make these referrals possible. But the UI agency would not need to directly support the outreach itself, as the web-broker would be compensated through its commission structure. That said, this blurring between a public benefit application process and a private, revenue-generating activity may generate discomfort and could raise privacy considerations under state law.

Note that states adopting a model like this – whether through assisters, state agencies, or web-brokers – also have a straightforward opportunity to conduct some randomized assessments of the effectiveness of the assistance model. This type of enrollment support does require resources, and whether funded through user fees or through broker commissions, those costs ultimately appear in premiums (where they are largely born by the federal government through increased premium tax credits). To the extent this type of referral partnership led consumers who would otherwise have enrolled without assistance to instead enroll with a paid broker commission or with assister help, that could increase costs. Assessing the effectiveness of the model will enable the state to calibrate appropriately.

Fully Integrated Application

Finally, states pursuing an overhaul of their underlying UI technology should consider steps to integrate a complete health coverage application into the UI application process. That is, the UI agency could operate as direct enrollment entity itself, offering a portal where individuals could apply for coverage in the Marketplace and in Medicaid. Under this vision, the UI website would operate a two-part application – the first an application for the UI benefit itself, and the second an application for health coverage – and applicant information could be shared across these components. States could determine the extent to which these application processes appeared unified to the consumer, choosing, for example, to integrate them into one application or offer them as separate modules.

Many existing web-broker entities are also technology development companies; some have partnered with state-based Marketplaces on various projects. Given their expertise in health coverage applications, the cost of developing an application portal for a state UI agency could be relatively low, especially in a context where the underlying UI system was also being redesigned. (Note that in this model, the state would buy technology from the web-broker vendor; enrollment would not be commission-supported.) The UI agency in a state-based Marketplace state could also work directly with the state Marketplace to develop an application portal. This type of approach offers the opportunity to create a more seamless and integrated enrollment experience.

For example, while some additional information, beyond what is collected in the underlying UI process, must be collected, this model could significantly reduce the application length for health coverage by avoiding duplicate entry of identifying information and some income data. It also allows the state agency to know exactly where consumers are in the health coverage application process and gives them the opportunity to follow-up with consumers throughout the recertification process to encourage submission. It offers the opportunity to generate specialized tools for estimating income that are tailored to the complexity associated with a household receiving UI. Finally, UI agencies may also want to consider allowing consumers to pay their share of the premium through a deduction from their UI benefit. This may be especially appealing for consumers with relatively small residual premiums, and the recertification process offers an opportunity to periodically confirm consumers have not obtained other coverage. Further, such a system would represent something close to truly automatic enrollment into coverage for those eligible.

Timeline for Action

Many of the options described above will take some time to implement. Building a fully integrated application, the capacity to seek consent for referrals, or interactive workflow elements will take time and technical resources. However, the recent surge in UI demand associated with COVID-19 has spotlighted the need for improvement in the technical infrastructure that supports UI programs. As the immediate crisis passes and at least some states prepare to make those needed upgrades, there is an opportunity to also take steps to support health coverage enrollment.

And even in the current environment, there may be steps UI agencies can take. States may find it very simple to add some basic and non-interactive information in a relatively-uncomplicated recertification workflow, or to send an email about coverage enrollment to existing customers. States should consider what they may be able to do now to help support coverage enrollment.

Marketplace and Federal Policy Options that Can Facilitate Coverage After Job Loss

The preceding section describes ways that state UI agencies could better support health coverage enrollment for those losing employer-based coverage. But even if a UI agency process successfully connects an eligible consumer to a health coverage enrollment, there are obstacles to enrollment that could deter take-up, particularly for Marketplace coverage with financial assistance. However, there are also steps that Marketplaces and the federal government could take it to remove these barriers and make it easier for this population to enroll.

Special Enrollment Period Verification and Eligibility

As described above, outside of the open enrollment period, a consumer must qualify for a special enrollment period (SEP) to be permitted to enroll. The federal government establishes the terms of SEPs for all states, and Marketplaces, federal or state, may add additional SEPs under existing authority. Loss of other coverage (including loss of job-based coverage) triggers a 60-day opportunity to enroll, so much of the population targeted here is eligible. However, the federal Marketplace and many states require consumers to document this eligibility.

The federal government indicates that 90% of people directed to submit SEP documents after a plan selection do so, implying that 10% do not. While some of the people who never submit documentation may find other coverage, it is likely that some of these people become uninsured. This group may also be particularly healthy since those in worse health are likely more motivated to ensure that they retain insurance coverage. Further, this estimate fails to count people who never select a plan because of the application complexity, including documentation. Removing documentation requirements and verifying SEP eligibility by an attestation under the penalty of perjury would make it easier for those losing job-based coverage to enroll.

Further, the existing SEP could be broadened to include not just those who lose job-based health insurance, but rather anyone who loses a job. Job loss results in meaningful changes in household finances, and will therefore change the generosity of coverage available in the Marketplace. Moreover, especially if coupled with the types of outreach efforts described above, a broad job loss SEP could induce higher take-up of the eligible population, and it would ensure that essentially everyone who applies for UI benefits is eligible for an SEP in the weeks surrounding their UI application.

Either of these options would create some adverse selection risk. Relatively unhealthy individuals might intentionally falsify their application and enroll through an SEP for which they are not eligible when they need health care, or only relatively unhealthy people made newly eligible by a job loss SEP might elect coverage. But given the very low take-up we see today and the experience in Massachusetts where continuous enrollment is permitted for most individuals, these risks may be overstated.

Income Verification

Another obstacle to enrollment is the income verification process. Individuals provide an estimate of yearly income in the Marketplace application process, and Marketplaces attempt to verify that information against payroll records and prior year tax data. (State-based Marketplaces access a wider set of income data sources.) If these data sources show an income different from that reported by the individual, the individual is directed to submit additional documents verifying their income – a time consuming process that resulted in hundreds of thousands of people losing financial assistance in the early years of Marketplace operations, though affects many fewer people today.

It is unnecessary to require individuals who have recently lost a job to go through this process. Their households have almost surely experienced a major change in income; they should simply be able to attest to having lost a job. Indeed, any estimate they provide will necessarily be based on information that is not reflected in official data sources and will reflect private household expectations (like the expected timeline for obtaining new employment). There is little that can be authoritatively verified in this circumstance, and recently unemployed households should be exempt from the process. This would avoid needless verification costs and make it easier for this group to connect to coverage, though it might lead to some increased tax obligations when financial assistance is reconciled and lead to some increased federal spending.

Tax Credit Reconciliation

Finally, note that the underlying fact that Marketplace eligibility rules are based on full year income poses complications for those who have recently lost a job. The newly unemployed are unlikely to have a concrete sense of expected annual income, given uncertainty about when they will find new employment and at what income. The fact that an underestimate could generate significant repayment liability when filing taxes may deter enrollment. Further, even if annual income could be accurately predicted, basing assistance on full year income means the higher-wage period preceding or following unemployment is averaged with the current lower-wage period. This may leave families responsible for paying a larger premium than they can afford during the time they are without a job and job-based coverage. Therefore, federal policy changes that move Marketplace financial assistance away from reliance on full-year annual income could enable the system to better serve those facing a coverage gap after losing their job, though these policies would generally carry federal fiscal cost.

The authors thank Kathleen Hannick for assistance in this research.

-

Footnotes

- As the authors note, these results may significantly understate the amount of uninsurance that results from mid-year coverage loss. The analysis assumes that the group recently losing employer coverage enrolls in ACA coverage at the same rate as other similarly situated people without employer coverage, but that ignores the depressed rate of mid-year enrollment, as discussed below.

- Publicly available administrative data on SEP enrollment is sparse, but similarly suggests very low uptake. During calendar year 2017, the most recent year for which complete data is available, 1.1 million people selected a Marketplace plan through a SEP in the states served by HealthCare.gov that year. This includes 670,000 people (60%) who applied through the SEP associated with losing other coverage. This is somewhat below what would be expected based on prior data showing that between 15,000 and 40,000 people per week used an SEP to enroll on HealthCare.gov in 2016, and that 800,000 people enrolled on HealthCare.gov via an SEP during four-and-half months in 2015, 59% through the loss of coverage SEP (excluding the special SEP associated with the 2015 tax filing season that was only available that year). Finally, in a 2020 rulemaking, the federal government reported that HealthCare.gov had verified SEP eligibility for more than 800,000 people during 2018 and 2019 combined, but not all SEPs require verification.

- Note that our finding differs from that of Graves and Nikpay (2017). Using MEPS-HC data, they examined the likelihood of a person transitioning from employer coverage to uninsured over 24 months, finding no significant difference between the 24 months ending December 2013 (12.6% of those with employer coverage become uninsured) and the 24 months ending December 2014 (11.9% of those with employer coverage become uninsured). The three additional years of post-period data available to us are likely the most important factor explaining the different result here, though we have not replicated their methodology.

- Federal rules provide a framework to allow UI agencies to share consumer information with other government officials, 20 CFR § 603.5(e), or with other third parties if the individual provides consent, 20 CFR § 603.5(d)(2).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).