Editor’s note:

This blog was originally published on

This is Africa

on May 16, 2016.

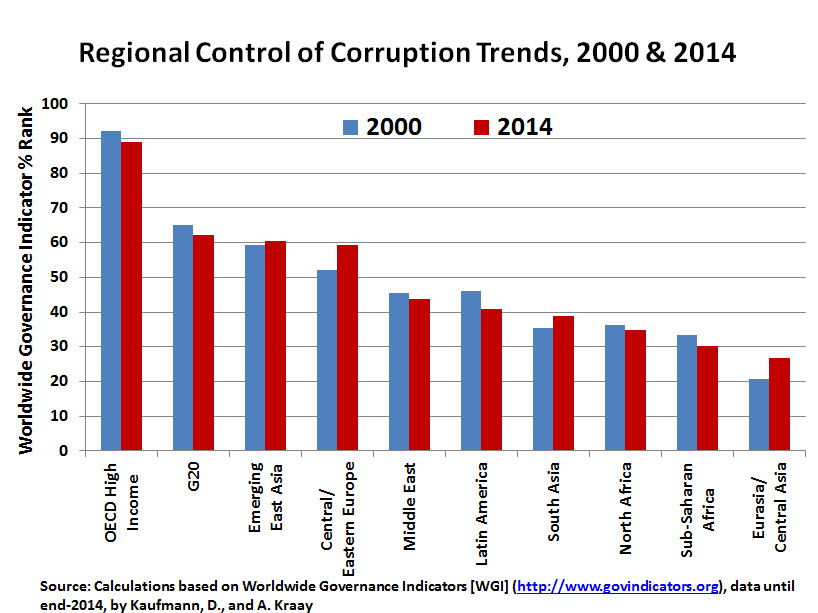

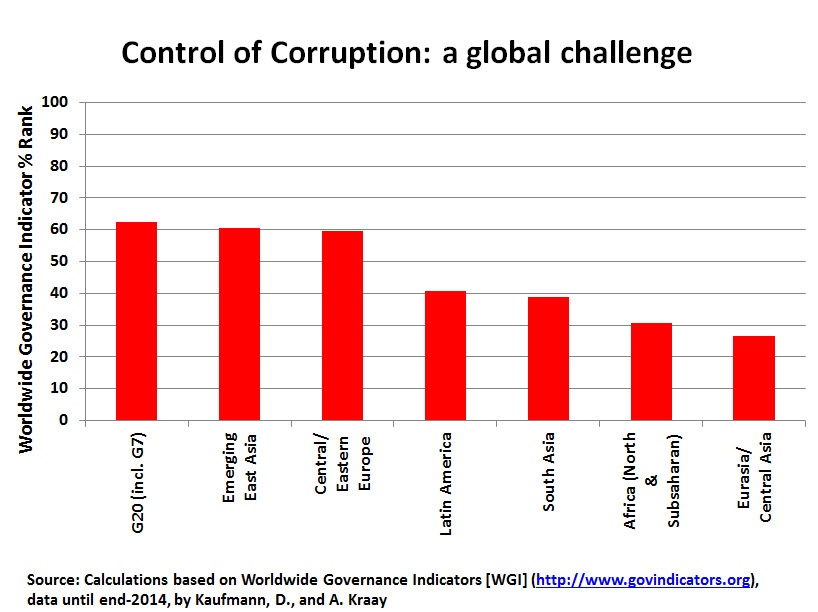

Corruption is way too easy in many places. Weak capacity, or will, to control it is the challenge. And, as Mo Ibrahim has said, high-income countries have gifted the corrupt with all manner of ways to hide their money. Corruption is a worldwide reality, one that afflicts—and originates in—the public and private sectors of industrialized, emerging and developing countries.

The good news for Africa is that 14 of its 54 countries, including Botswana, Ghana, and Senegal, rank in the top half of all countries in the Worldwide Governance Indicators “control of corruption” category. Yet 34 African countries are in the bottom third. This translates to a major waste of public resources, loss of tax revenues, and reduced investment, and is thus a major brake on development and growth—not to mention equality and security.

The recently concluded anti-corruption summit that took place in London, hosted by the U.K.’s Prime Minister David Cameron, presented a number of practical strategies for making corruption more difficult. What is needed is a concrete and detailed strategy and agenda for specific reforms. To that end, participant countries—including Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, and Tunisia—committed to tangible, pragmatic actions, and civil society and anticorruption experts provided further recommendations. Here, we look at some of the implications for Africa.

Commodity trading transparency and oversight

From 2011 to 2013, sub-Saharan Africa’s top 10 oil-producing governments sold crude worth $254 billion, an amount equal to 54 percent of their total public revenues. For Angola, Congo-Brazzaville, Libya, and Nigeria, these oil sales constitute the country’s largest single revenue stream. Swiss trading companies purchased $55 billion worth of oil from African governments in that time. But despite their size, oil sales are usually conducted in secret.

The need for transparency in resource trading featured prominently in summit discussions. The U.K. and Switzerland agreed to enhance company reporting of payments to governments for sales of oil, gas, and minerals. The logical next step for these jurisdictions (as well others like the U.S. and Singapore) is to expand regulation to cover such transactions. Ghana, the state oil company of which sells several oil cargoes a year to traders, also endorsed greater transparency in this area.

Open contracting and procurement

A growing number of governments are moving toward open contracting, which emphasizes transparency, open data, and active monitoring. The summit communiqué summed up the mood: Public procurement should be “made public by default.”

Nigeria committed to open contracting, beginning with key sectors of public spending, such as health, education, power, roads, and oil refining; upstream oil contracts were conspicuously missing from this commitment. Ghana also agreed to work towards open contracting, and explicitly mentioned the need to target deals in the extractives sector. Along with a few other countries, Ghana is also ceasing business with public procurement firms that have engaged in corruption. Commitments from Tanzania and Kenya on this were much weaker, while South Africa left it out altogether.

Beneficial ownership reporting

In the wake of the Panama Papers, the topic of secret companies featured prominently at the summit. And the discussions were refreshingly balanced, with ample attention to how jurisdictions like the U.S., the British Virgin Islands, the Seychelles, and Mauritius make it far too easy to establish secret companies in order to receive bribes or launder illicit funds.

Reporting a company’s “beneficial owners”—the real people behind it—makes it more difficult for corrupt actors to hide. African summit participants diverged in their willingness to take up this task. Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria committed to publicly disclose beneficial ownership registries, and Tanzania said it would do so for the extractive industries.

Of course, action in Africa will not be enough. A handful of northern countries including the U.K., the Netherlands, and France have agreed to publish their beneficial ownership registries. But many other jurisdictions, including secrecy havens like some U.S. states and the Cayman Islands, are only willing to make some data available, and even that only to law enforcement authorities.

More work remains; the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), to which several African countries are party, is doing some of it.

Global responsibility

International organizations also have a major role to play. We applaud IMF head Christine Lagarde for concrete commitments she made at the summit last week, vowing to incorporate governance and corruption standards into the IMF’s formal country review mechanisms and to go further on fiscal transparency (including in extractives).

The London communiqué specified the Open Government Partnership as a critical tool for monitoring commitments made at the summit, and, together with EITI, with its newly beefed-up standard, will remain a critical forum for progress.

Together, commitments at the summit represent exciting and useful approaches that emphasize transparency, open data, and global action. Concrete follow-through at the country level, supported by global institutions and the actions in the U.K., U.S. and the rest of the G-7, is now essential.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

London calling about corruption: How will countries rich and poor answer—and what does it mean for Africa?

May 23, 2016