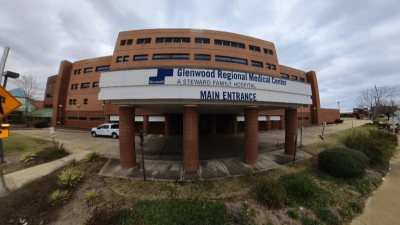

The monitor that had been tracking Mearl Hodge’s heartbeats started to show an abnormal rhythm. So, a technician at Glenwood Regional Medical Center alerted nurses that the electrodes that should have been affixed to Hodge’s chest seemed to have popped loose. No one checked. It was a granddaughter, arriving for a visit 20 minutes later, who discovered that her grandmother no longer had a pulse.

The circumstance of Hodge’s death in northeast Louisiana is among more than 650 documented instances of deficient care at nearly three dozen hospitals across eight states that were owned by Steward Health Care before the entire system collapsed last year in a spectacular bankruptcy. Hodge’s death, four days after she was admitted to Glenwood with covid the winter of 2022, triggered an inquiry1 by the Louisiana Department of Health. Beyond the unattached heart monitor leads, the mask helping Hodge, 90, to breathe was sitting, useless, on her stomach. And though her medical chart made clear she wanted to be resuscitated in any emergency, the staff hadn’t tried.

For these mistakes, the state health department fined Glenwood $1,750.2 Light as that penalty was for a life, what is uncommon about the case is that the hospital was fined at all. The scarcity of sanctions when some Steward facilities made even grave errors is part of a pattern in government regulation of America’s hospitals that we identified in a case study of Steward Health Care. The collapse of Steward has attracted considerable attention, mainly depicted as a poster child for the perils of for-profit hospital owners fueled by self-enriching executives and their private equity patrons. In contrast, our examination of the Steward system points to a less obvious culprit: Across the country, oversight of hospitals by states and the federal government is inadequate—at times weakly enforced, at times absent.

This portrait of the feeble regulation of a troubled health system emerges from our data analysis of Steward’s hospitals and review of current regulatory practices. The multi-prong analysis reveals substantial flaws in how government oversees hospitals. On the one hand, main ways the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) require U.S. hospitals to publicly report on their finances and their quality failed to point to Steward’s deepening fragility.

On the other hand, two sources of data that we analyzed—information that regulators do not routinely track—make clear that the company’s hospitals were increasingly in trouble. One is a roster of nearly 130 lawsuits that mounted as the bankruptcy neared; vendors—from suppliers of medical devices to air-conditioning—went to court, alleging that Steward neglected to pay its bills. The other is a growing pile of hospital deficiencies—flaws, including in Mearl Hodge’s care, of varying severity that states examined in response to complaints.

This combination—public data that didn’t show the problems, revealing trends that regulators didn’t watch—does not suggest that many of the United States’ hospitals are poised to fail. A slim body of research into the more than 450 hospitals with private equity financing indicates that they tend to be more problem-prone. But those account for a small share of the nation’s for-profit hospitals, and evidence of whether the entire group has lower quality than nonprofits is mixed. Still, the lax regulatory climate means that state and federal early warning systems for troubled hospitals are largely absent. As Jonathan Blum, who held senior roles at CMS during the Obama and Biden administrations, said in an interview: “We need to build some sentinels. . .to catch things before a crash happens.”

In the meantime, certain hospitals and the communities that rely on them can be vulnerable. That is especially the case now that looming funding cuts to Medicaid and other federal health care programs—set forth in a broad tax and spending law that Congress adopted in June and other recent policy shifts—are widely predicted to erode the financial underpinnings of rural and other already-strapped hospitals. As such, hospitals struggle to cope, some may hunt for new, deep-pocketed owners.

We need to build some sentinels. . .to catch things before a crash happens

Jonathan Blum, former principal deputy administrator and chief operating officer, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

To make clear what we learned through this case study, we will start with a quick history of Steward’s twisting path, then depict our data findings. From there, we will focus on the company’s intersection with one state government as a microcosm, offer a few ideas that could improve hospital oversight, and end with a reminder of the human cost of Steward’s troubles.

The rise and fall of Steward—a brief history

Massachusetts, Steward’s birthplace, is a hub of academic medical centers. It had never been home to a for-profit hospital financed by private equity—an arrangement in various aspects of U.S. health care in which investors look for high returns. But in this century’s early years, a local Roman Catholic health system called Caritas Christi was faltering after a widespread priest sex scandal was revealed, a scandal that financially drained the Archdiocese of Boston. Eventually, Caritas began looking for a buyer, and Massachusetts officials joined the search. They were having little luck, especially finding one willing to heed Caritas’s no-abortion policy and other Catholic values.

So, Massachusetts officials viewed it as good fortune when Ralph de la Torre, a prominent cardiac surgeon in Boston who had become Caritas’s chief executive two years earlier, proposed what he said would be a new model of care. A fan of value-based payment models—accountable care organizations (ACOs) in which providers share in savings and, sometimes, financial risks—he argued that these community hospitals could offer good treatment at relatively low expense. In 2010, the system affiliated with Cerberus Capital Management, an established private equity firm. In purchasing Caritas, Cerberus pledged to solidify its underfunded pension system, shore up the half-dozen hospitals and, for the first five years, be monitored by Massachusetts’ attorney general. The system would be renamed Steward Health Care. With certain conditions, the attorney general and a judge approved the deal.

Though the fledgling system made some hospital improvements, Steward didn’t always adhere to the deal’s terms, as we describe in more detail below. And, under de la Torre’s leadership, it quickly became clear that the company had larger ambitions. Three months after Steward was formed, the fledgling system tried—and failed—to take over a half-dozen Florida hospitals, including Jackson Memorial, a public safety-net anchor in Miami. Later in 2011, Steward bought four more Massachusetts hospitals and another in 2012. But Steward’s big growth spurt started in 2016, just after the state monitoring ended, when the system entered into a deal with Medical Properties Trust (MPT), a major real estate investment trust, a type of company that pools money from many investors to buy and own income-producing real property. MPT bought all of the Steward hospitals’ buildings and land in a “sale-leaseback” arrangement, providing the system with cash in exchange for escalating rents. Steward, together with MPT and Cerberus, went on a buying spree, expanding for the first time beyond Massachusetts. Less than a year later, it owned 36 hospitals in 10 states—adding facilities in Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Louisiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Utah.

In none of the other states into which Steward spread did regulators have a role reviewing the purchases, according to our analysis of health care “transaction” laws, compiled by the National Conference of State Legislatures. In some of the states, such as Arizona, an attorney general reviews only sales of nonprofit hospitals; Steward grew almost entirely by acquiring hospitals that already were for-profit. Other states, such as Florida, review sales of nursing homes, but not hospitals. Still others, such as Texas, do not oversee any health facility sales.

As the company expanded and contracted, financial troubles, staff and supply shortages, and de la Torre’s voracious spending on luxuries—including a $30 million, 190-foot yacht—were materializing. Steward sold seven hospitals in Ohio, Colorado, and Utah. In January of 2024, the Boston Globe broke the story of a 39-year-old woman who died of profuse bleeding from her liver the day after giving birth at Steward’s St. Elizabeths Medical Center in Boston; an unpaid vendor had repossessed common metal coils that doctors use to stem internal bleeding.

Less than four months later, on May 6, 2024, the whole Steward system filed for bankruptcy in Texas, where the company had moved its headquarters six years before. That September, the Senate unanimously held de la Torre, the CEO, in criminal contempt for defying a subpoena to testify about his company. This summer, the remnants of Steward sued de la Torre, who resigned in the fall of 2024, and three others, accusing them of “greed and bad faith misconduct” that had sunk the company—allegations a spokeswoman for the former CEO denies.

The bankruptcy set off a scramble, overseen by the bankruptcy court, for new owners of Steward’s by-then 31 hospitals. Two in Massachusetts closed outright. As de la Torre was in France with his wife, attending the Olympics’ equestrian events at the Palace of Versailles, community members losing their hospital and workers losing their jobs were protesting outside Carney Hospital and Nashoba Valley Medical Center, as well as Boston’s gold-domed statehouse.

Hospital regulation and its data

The tale of Steward crystalized a central question for us: When problematic actors take over a hospital system, who is minding the store?

This overarching question led us to consider the government’s role in shielding the public from hospitals providing unsafe and ineffective care. To explore this question, we first examined two main types of data that virtually every acute care hospital in the United States is required to submit each year to CMS. One type is a set of financial data, known as Medicare cost reports. The other is a set of quality metrics, known as Care Compare, which forms the basis of a star rating system CMS maintains for consumers.

Finances

Nearly every acute care hospital that treats patients on Medicare must provide CMS an annual cost report containing specified financial information. In our analysis of these reports, we looked at four measures that are routinely considered indications of a hospital’s financial condition. They are operating profit margin, net profit margin, current ratio, and equity financing ratio.3 CMS makes these cost report data publicly available.

For each of these measures, we compared the average4 for Steward’s hospitals against the average for U.S. hospitals overall. We also compared these measures with slightly different audited financial statements for the entire Steward system. Unlike with nonprofit hospitals and private ones that are publicly traded, such audited statements are not routinely available for health systems backed by private equity—but they were for Steward.5

Between 2011, the first full year of Steward’s existence, and 2023, the most recent year for which data are available, we found that the company’s hospitals did not appear substantially different from U.S. hospitals overall. However, audited financial statements for the whole Steward system, available in separate public records, reveal that, for all four measures we analyzed, the company struggled from early on.

Here is what we found for each of the four metrics:

Figure 1 shows that, from 2011 to 2019, the average operating profit margin reported to CMS by each individual Steward hospital appears to be outperforming the average for all U.S. hospitals. However, system-wide audited financial statements from that first year through 2021, the most recent year’s data available, indicate that Steward was struggling from its inception. For the period 2012 to 2022, Steward reported to CMS operating margins of over 5%, while its audited financial statements showed operating margins that were negative in all but two years.

Figure 2 shows that, unlike in the operating margin, the average net profit margin for the individual Steward hospitals was weak from the start, below the national average for most years, until the figures reported to CMS rose considerably shortly before the bankruptcy. The individual hospitals appear in better shape than the health system in all but three years.

Figure 3 reveals that, in Steward’s early years, the average current ratio of assets to debts for individual hospitals tracked closely with system-wide audited financial statements. But starting around the time that Steward affiliated with Medical Properties Trust in 2016, they quickly diverged, with the individual hospitals’ financial data reporting less debt than the system-wide statements. The audited system-wide financial statements show that, starting its first full year in 2011, Steward was struggling, with its current ratio three times lower than the national average for U.S. hospitals.

As Figure 4 indicates, the equity financing ratio from Steward’s system-wide audited financial statements was, from the outset, below both the national average and the ratio experts regard as appropriate. However, this ratio plunged once Steward affiliated with Medical Properties Trust in 2016. And starting around that time, the ratio was consistently far below the average reported by the company’s individual hospitals. Most dramatically, Steward’s system-wide average was negative 35% in 2021, compared with an average for all U.S. hospitals that year of 60%.

So, what accounted for the discrepancies between what Steward’s individual hospitals reported and its audited system-wide data? The discrepancies reflect that the company shifted many expenses to the central office—a common practice among health systems that Steward took to an extreme.6 As a result, the cost reports are “not a valid data set for analyzing the financial condition of the hospitals,” as Nancy Kane, an emerita professor of health policy and management at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, said in a conversation for this case study.

As KFF noted last year in a report on gaps in hospital financial information, the data submitted in cost reports for individual hospitals is not standardized or rigorously scrutinized—and does not reflect the financial condition of their parent health system. Plus, these reports typically lag by a year or two.

More fundamentally, these public cost reports are not a tool for federal oversight of hospitals’ condition. CMS uses the reports to help ensure that Medicare is paying hospitals correctly, not to monitor their financial health.7

So, are states filling this oversight gap? Of the 10 states in which Steward operated, seven require hospitals to report at least some financial data and make it publicly available, according to a review we did of state financial transparency laws. But just three—Colorado, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania—say they currently analyze the data for hospitals’ expenditures or financial condition.8

Quality

As with the financial data, our analysis found that important measures of hospitals’ quality did not reveal the trouble that was occurring at many of the Steward facilities. Using CMS Care Compare’s hospital data, we analyzed four metrics. They involve serious medical complications, patients who leave an emergency department without being evaluated or treated, pneumonia deaths within 30 days of discharge, and readmissions.

For each of these four, we examined the average performance9 reported by the company’s hospitals in comparison with the national average for U.S. hospitals from 2013, the earliest year for which CMS has consistent data, to 2024, when Steward declared bankruptcy. We also focused on the individual performance of five Steward hospitals that, we knew from other sources (see discussion of hospital deficiency citations below), were especially problem-ridden. For the most part, even those five hospitals did not appear markedly worse in quality than the average for hospitals nationwide.

Here are what four metrics show:

The average rate of serious medical complications for Steward’s hospitals was consistently near that of the nationwide hospital average. Only one hospital in Figure 5, Mountain Vista Medical Center in Mesa, Arizona, had a substantially higher rate than the national average for most of the years we analyzed.

Figure 6 shows that the average percentage of patients who left a Steward hospital emergency department without having been evaluated or treated closely paralleled the nationwide hospital average and, except for 2024, was slightly lower. Most of the five individual Steward hospitals we singled out as problematic had rising rates of untreated emergency department patients in the final years before the company’s bankruptcy.

Deaths from pneumonia within 30 days of a patient’s discharge are considered by many experts to be a better harbinger of a hospital’s quality than mortality from other causes, because some patients develop pneumonia while hospitalized. Within the Steward system, Wadley Regional Medical Center in Texas and Glenwood in Louisiana had substantial increases in pneumonia deaths in the few years preceding Steward’s bankruptcy, but the rate for the system as a whole consistently hovered near the average for U.S. hospitals (Figure 7).

Throughout the dozen years we analyzed (Figure 8), the average rate at which patients were unexpectedly readmitted for all reasons to a Steward hospital remained close to the average for U.S. hospitals. Even as the bankruptcy neared, most of the five problem-ridden hospitals did not show any substantial rise in readmissions.

In the end, our analysis showed that the main metrics that CMS collects each year from U.S. hospitals about their financial condition and their quality failed to provide much sign of Steward Health Care’s deteriorating condition as the system was heading toward collapse.

So, we wondered, weren’t there any clues that could have warned that the health system was in trouble? It turns out that there were—in two types of information that state and federal regulators do not routinely scrutinize.

The clues

Having seen news accounts about lawsuits filed by vendors who alleged that Steward wasn’t paying its bills, we studied this litigation. We relied in part on a schedule within the bankruptcy court docket that lists lawsuits by Steward creditors that were still unresolved within a year of the bankruptcy filing. The schedule categorized these lawsuits, and one category, “breach of contract” cases, consisted of complaints over allegedly unpaid bills. We found additional lawsuits in an offshoot of LexisNexis called CourtLink, which contains cases filed in all federal courts and many state and local courts.

In all, we reviewed 127 legal complaints against the Steward system or its individual hospitals in which vendors were suing to get paid. These cases totaled $139 million in allegedly unpaid bills.10

Unlike the financial and quality data collected by CMS, these lawsuits show a clear pattern leading to the system’s collapse. The number of suits brought by vendors over unpaid bills escalated in 2022, when nine filed legal complaints, then soared to nearly 60 in 2023 and 47 more in the first months of 2024, before May’s bankruptcy filing.

Many of these vendors had been working with Steward for several years, although some had longer relationships with the company. Most waited a year or two after they allegedly had not been paid to bring the suits, signifying that the company had trouble covering bills earlier in this decade.

For instance, one small company, Eklund Refrigeration, sued11 Steward for $32,640 in March 2023, contending it had sent 37 invoices for air-conditioning service to two Arizona hospitals after it had last been paid in 2021. The suit was filed about one and a half years before Arizona health officials stepped in, shutting down one of them, a Phoenix psychiatric hospital called St. Luke’s, when the broken air-conditioning caused the temperature inside to reach 99 degrees F. in the August heat.

Figure 9 notes that the lawsuits spanned a range of services for which hospitals routinely hire outside companies. Medical equipment and supplies, as well as maintenance services, were the most common.

The typical sums for which vendors sued varied considerably by the type of service. As Figure 10 shows, the largest cases involved contract staffing, with the average lawsuit seeking nearly $2.4 million in allegedly unpaid bills.

As lawsuits by disgruntled vendors provided vivid insight into Steward’s mounting financial problems, we similarly found that investigations of hospitals—spurred by complaints by patients, relatives, or staff—revealed deteriorating quality. The investigations, known as surveys, are conducted by state health agencies on behalf of CMS. If a survey establishes that hospital care or conditions were deficient, state officials write a report and send a copy to CMS. The reports are kept in a federal public database, and states also keep them, though we did not find that either layer of government used the incidents to track the performance of Steward hospitals.

The federal and state records show that hospitals owned by Steward had nearly 680 deficiencies. They climbed from 13 in 2020 to 108 in 2024. The number of Steward deficiencies per hospital in 2024 was about three and a half times as many12 as the average for all U.S. hospitals in 2023, the most recent available.

Federal health officials have defined three deficiency levels. From the least severe to the most, they are called standard, condition, and immediate jeopardy, with the latter meaning that a flaw was so significant it caused death or injury or easily could have. As Figure 11 shows, we found that deficiencies grew at every severity level shortly before the system collapsed.

The five hospitals with the greatest number of deficiencies over the past five years were the ones we singled out for the analysis of hospital quality data above, because these deficiencies suggested they were performing poorly. The Medical Center of Southeast Texas in Port Arthur, about 90 miles east of Houston, was cited nearly 90 times for deficiencies since Steward bought it in 2017, with a dozen of them classified as immediate jeopardy cases. The hospital had the most deficiencies in the company and the most in the immediate jeopardy category. In a 2018 case, investigators from the Texas Health and Human Services Commission found that the hospital was using surgical instruments and other equipment beyond the date when they could be guaranteed to be sterile. And operating room staff were not wearing protective shoe covers to make certain they didn’t bring in contaminants from outside.

Even hospitals with fewer deficiencies were found at times to have dramatic flaws. In March 2024, surveyors from the Pennsylvania Department of Health cited Sharon Regional Medical Center, on the state’s western edge, for an immediate jeopardy. The facility lacked the proper supplies for 29 surgery cases, according to the investigation records, which say that, for two patients, “cardiac cases…were attempted but unable to be completed.”13 Some surgical supplies that were available had not been kept clean and sterilized, the records say, while the hospital temporarily stopped performing endoscopies because it had not properly maintained necessary equipment.

In Utah, Salt Lake Regional Medical Center was cited for an immediate jeopardy by the state’s Department of Health and Human Services for an incident the winter of 2023 in which a wheelchair-bound patient, who wanted to wait inside for a relative to take her home, was, instead, dropped off by hospital security staff at a frigid bus stop, where she died, according to state records that cite failed discharge planning, plus a confidential conversation for this case study with a quality control expert familiar with the incident.

CMS is not authorized to fine hospitals for deficiencies. Its only remedy is to ban a facility from Medicare and Medicaid—a step so draconian that it seldom happens, because depriving a hospital of revenue from these public insurance programs would threaten its existence. More often, federal health officials, or state regulators to whom they delegate responsibility, warn hospitals that they face being dropped from the programs unless they correct deficiencies—and then accept the hospitals’ correction plans.

In practice, then, any penalties for hospital flaws are up to the states. According to staff at the Pennsylvania and Utah health departments, those agencies typically prefer to nudge hospitals to improve.14 They told us that they issued no fine against Sharon or Salt Lake Regional for these immediate jeopardy cases or any other deficiency when Steward owned those hospitals.

In Texas, the Health and Human Services Commission issued one fine, totaling $7,200, out of the 21 immediate jeopardy deficiencies it cited at Steward hospitals, according to records. The penalty followed a survey in early 2024 at Wadley Regional Medical Center in Texarkana. That investigation, records show, found a malfunctioning emergency room call system, dirt and debris on food carts and other spots, and leaks through ceiling tiles. After listing these and other flaws, however, the state’s May 2024 notice told the hospital the fine “was not a demand for payment,” if it was in bankruptcy. As of that month, Steward was. Eventually, the company paid anyhow.

Steward in Massachusetts

In Steward’s birthplace, Massachusetts, the company’s hospitals racked up 310 deficiencies from the system’s beginnings until its hospitals there closed or were sold in the bankruptcy. The citations included an immediate jeopardy one for the case at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, in which absent surgical coils contributed to a patient’s death after giving birth.

The state, however, does not have a system of financial penalties for such flaws.15

That lack of punishment is part of an uneven pattern of oversight of Steward that we found in Massachusetts. In some ways, the state has a more elaborate health-policy apparatus than most of the country. And yet, at important moments, Massachusetts officials allowed the company to skirt agreements and the law.

For instance, when then-Attorney General Martha Coakley in 2011 approved Steward’s purchase of Quincy Medical Center—a century-old, financially wobbly hospital south of Boston—the agreement’s terms said the company could not sell or close the facility for at least five years. And under Massachusetts law, hospitals must provide at least 90 days’ formal notice to health officials before shutting down a hospital or ending certain services.

Still, three years after Steward took over Quincy, with less than two months’ notice, the company told the state the hospital was about to close. At first, the attorney general’s office said it might take legal action to keep it open. Neighbors and hospital staff jammed a public hearing and pleaded for the state to block the plan. In the end, Quincy closed, and the attorney general required only that Steward keep an emergency department and a few other services nearby for at least two years.

We interviewed Rep. Ronald Mariano, the Massachusetts House Speaker who represents Quincy, and asked whether the attorney general did enough to prevent the city from becoming the state’s largest without a hospital. “The short answer to that is no,” Mariano replied.

The dispute over Quincy’s closing occurred during the final weeks of Coakley’s tenure as state attorney general before Maura Healey replaced her in early 2015, starting the first of two terms as attorney general before she became governor. That December, the attorney general’s office produced a final report from its five years of monitoring Steward.

In describing the parent company’s financial condition, the 60-page report says that Steward’s audited financial statements from the 2012 to 2014 fiscal years “show consecutive years of substantial losses,” with a net loss for the latter year of about $78 million. For the individual hospitals, the report said their profitability had improved. In keeping with our findings, the report noted that the hospitals appeared in better shape partly because expenses were redistributed to the parent company.

In an interview with Gov. Healey, she told us, “We issued that report, making clear that there’s a problem here. . .It was very clear about Steward’s financial problems.”

The report’s summary, however, had a positive tone. It listed concerns that had surrounded the creation of the for-profit hospital system with private equity financing, including price increases, revenue diverted to satisfy investors, and unprofitable types of service, such as mental health care, squeezed in favor of more lucrative services. “Five years later,” the report said, “the most dire of these concerns have not come to pass. Steward has kept the former Caritas system intact and operated the system as it had proposed.”

That conclusion, however, conflicts with that of a consultant who worked as a contractor for the attorney general’s office to analyze the company’s finances for the report. The consultant, Kane, the emerita Harvard public health professor, said in an interview for this case study that, by 2014, the final year of data available for the report, Steward “did not look healthy. They were still losing gobs of money, and they were piling on debt. We just didn’t see how they were going to pull it off,” Kane said. “We gave [the attorney general’s office] a draft of the financial position, and they really downplayed how dire the situation was. . .taking out some of the more contentious negativity,” she said, “We did try to. . .stop that, and we complained, but it was their work product.”

I think that the growth of private equity and the for-profit model outpaced the growth of a regulatory regime to meet that evolution. . .we didn't have the right tools to deal with some of this

Maura Healey, governor of Massachusetts

In retrospect, some health care experts in Massachusetts we interviewed view the five years of monitoring as too brief and shortsighted, though they note that the state at the time lacked other options for new owners to take over the fragile Caritas Christ hospitals. Healey said during our conversation that the attorney general’s office did not have a basis to extend the oversight, saying that Steward “had satisfied everything they needed to under the terms of the five-year monitoring. . .There was no way for that [monitoring] to continue.”

John McDonough, a Harvard public health professor and former Massachusetts state lawmaker, told us, “Once the oversight ended, then it was party time for Steward.”

Steward’s affiliation with Medical Properties Trust, and its sale-leaseback arrangement, began nine months after the monitoring ended. Because this was a real estate deal, not a health care one, Massachusetts did not have regulatory power to review it.

The following year, 2017, Steward sued16 a Massachusetts agency with which it had been feuding for four years. An uncommon independent agency, the Center for Health Information and Analysis (CHIA), was created in 2012 to collect and publish health care data, including about hospitals. No other hospital had objected to submitting what was required, but Steward soon refused to provide CHIA its audited financial statements, contending that, for a for-profit system, they contained sensitive business information the company needed to protect.

Using the only leverage it had to try to compel Steward to comply, CHIA levied fines of more than $300,000. As Adam Boros, the agency’s first director until 2016, said in a conversation for this case study, “the fines were not big enough to motivate them in any way.”

Finally, Steward sued, arguing the state’s requirements of financial data did not apply to it. A judge eventually ruled against the company, but the case was still on appeal when the system filed for bankruptcy. In the suit, Steward said17 that, while it was sparring with CHIA over the financial statements, the company negotiated an agreement with the attorney general’s office to provide such information for its monitoring with a confidentiality guarantee. Speaking on the condition of anonymity for this case study, two former senior Steward executives confirmed that this happened.

Healey said the idea that the attorney general’s office “could have just shared it with CHIA. . .that’s a completely false construct. . .We were advocating strongly and aggressively in court” to pry the data from Steward.

“You know,” the governor said, “if that information had been provided sooner, the state or federal government might have been able to take action to head off some of the harm that ultimately came to pass.”

Mariano, the House Speaker, recalled starting to get calls from friends of his in the world of health care, telling him tales of lack of equipment and staff at Steward’s facilities, along with money that de la Torre and other top officials were diverting to themselves. As the House speaker said, “The whole thing was getting crazy.”

The Steward trouble “wasn’t out of sight,” said David Cutler, a Harvard professor of economics who until recently was a board member of the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission, a body that focuses on health care costs and affordability. “People were looking at it and saying, ‘What the hell are they doing?’ But there was nobody who could do anything about it.”

In our conversation, Healey said, “I think that the growth of private equity and the for-profit model outpaced the growth of a regulatory regime to meet that evolution. . .from my perspective, we didn’t have the right tools to deal with some of this.”

In February 2024, weeks after the Globe broke the story of the patient who died after childbirth, the governor dispatched a stern letter to de la Torre. Healey demanded that the company improve its supplies and staffing, submit to more monitoring by state health officials, and immediately disclose financial documents. And, the governor’s letter said, it was time for Steward to leave the state.

After the bankruptcy filing that May, state officials worked with the company and other players in the Massachusetts health care world to find new operators for the Steward hospitals, in some instances spending state money to tide hospitals over. “We were able to save six of the eight,” the governor told us.

Eleven months later, a week after New Year’s 2025, Healey signed into law a bill that expands hospitals’ oversight. The law increases the penalty for not providing CHIA the required data from $1,000 to $25,000 for each violation. For the first time, it requires private equity firms and real estate investment trusts (REITs) to appear with other health care entities at an annual public hearing on health costs. It forbids hospitals from getting a license if their main campus affiliates with a REIT, though such arrangements that already exist are allowed to continue.

Looking back on the 14 years Steward was in Massachusetts, Healey said, “More and better legal tools needed to be in place and, you know, that’s partly accomplished through this legislation.”

But the governor added, “we should be looking to see what else needs to happen.”

Lessons for policy

At its core, our case study has centered on exploring this question: When problematic actors take over hospitals, who is minding the store? Our data analysis and examination of state and federal policy yields this answer: Almost no one is doing enough.

The failings, as we see it, fall into three main camps. Each warrants strengthening at state and federal levels to protect these crucial medical facilities—and the patients who rely on them—from the kind of problems that festered at Steward’s hospitals. These are our thoughts in broad strokes. Additional work will be needed to define how best to accomplish them.

- Collect better data on hospital and health systems’ finances and hospital quality that is more likely to detect problems early—and use that information for more rigorous oversight of facilities’ performance.18 At the federal level, this will mean rethinking the caliber, standardization, and analytic depth of the data hospitals must report to CMS. At the state level, this often will mean establishing explicit responsibility within health agencies for such monitoring and analysis, as well as publicizing the results. The goal throughout should be to detect signs of trouble at hospitals and their parent health systems in close to real time, rather than mainly responding retroactively to complaints and catastrophic events.

- Raise the stakes for hospitals that provide substandard care. Federal and state health officials are reluctant to levy fines that would cause hospitals to weaken financially, particularly in urban and rural communities that already are medically underserved, for fear of eroding people’s access to health services. But the current mixture of light penalties and no penalties for deficient care should be stiffened to deter hospitals from stinting on staff, supplies, and other ingredients of good care. And government officials should employ tools apart from penalties to coach hospitals to improve.

- Change regulatory practices in most states in which the sale of for-profit hospitals often gets less scrutiny than that of their nonprofit siblings. States need the leverage to block or place conditions on a hospital acquisition and its financial arrangements if they do not appear to be in the public’s interest, including in deals that involve private equity firms or real estate investment trusts. Federally, agencies beyond the Department of Health and Human Services—such as the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Trade Commission—should play larger roles in keeping an eye on hospital consolidation and sale-leaseback arrangements.

The collapse of Steward Health Care has served as a poster child in illuminating the failings of current regulation. In Washington and in some statehouses, this neon example has spurred discussions about what more could be done. So far, relatively little of that recent discussion has led to change.

For instance, in January, days before the Biden administration ended, federal officials issued a report on health industry consolidation, including hospitals such as Steward’s with private equity financing. The 37-page report by the Departments of Health and Human Services and Justice and the Federal Trade Commission said that, in gathering public comment, the agencies had repeatedly heard advice that “HHS should do more to improve the quality of the data” it collects about health facilities’ owners, prices, staff levels, and patient care.

There are no signs of any further consideration of the report.

On Capitol Hill, the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee conducted a hearing into Steward’s troubles in September 2024—theatrically placing a name tag for de la Torre, the company’s then-CEO, at an empty witness chair he would have occupied if he hadn’t defied a subpoena to appear.

The hearing occurred two months after one of the committee’s members, Sen. Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.), had introduced legislation with Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) that would have clamped down on private equity in health care. The bill did not receive a committee hearing. According to Markey’s staff, he plans19 to reintroduce the legislation during the current Congress, but has not done so yet.

More recently, another HELP committee member, Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.), issued a report in August on a similar theme, decrying the effects on his state of the other private equity-financed health system, Prospect Medical Holdings, that declared bankruptcy. When Prospect took over three Connecticut hospitals, the report said, “they cut corners, squeezed staff, eroded patient care, and drove these hospitals into bankruptcy, leaving economic uncertainty for these communities in its wake.”

Murphy’s report notes that the Connecticut legislature failed to pass two bills that would have strengthened the state’s review of health care transactions or outright banned private equity firms from owning hospitals. According to Murphy’s staff, his office is developing federal legislation.20

In other words, the early stirrings of interest on Capitol Hill in addressing these issues have not yet been subject to real scrutiny.

Across the country, 18 states have considered legislation during the past few years that would give attorneys general or health agencies greater latitude when health care facilities are sold and acquired. Of those states, 11 passed bills. Most of the new laws require notification of the state of a prospective sale if the transaction involves enough money, but do not give that state the power to stop it.

In 2021, before Steward’s troubles had crescendoed, Oregon adopted what remains the nation’s stiffest law dealing with hospital and other health care transactions. The law sets forth detailed procedures for the Oregon Health Authority to evaluate whether a sale, merger, or acquisition will contribute to Oregonians’ access to affordable health care, then approve or disallow it—or allow it under certain conditions. During the first five years of an approved deal, state regulators must examine three times the effect on health care costs and whether the facility is obeying any conditions the state set. The law also requires a study every few years of the effects of health care consolidations in the state, including an analysis of their impact on the quality of care.

Based on our review, Oregon is the only state that routinely evaluates a hospital’s condition after a transaction takes place.

Apart from Massachusetts, discussed above, none of the 10 states that have had Steward’s hospitals have adopted laws to change their role in health care transactions. In four states—Colorado, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Texas—bills have been introduced but not passed.

In Louisiana, only nonprofit hospitals must notify the state attorney general if they are being acquired. And the Bayou State’s certificate of need law gives the health department the ability to review whether facilities are needed if they are nursing homes, home and community-based services, hospices, mental health rehabilitation centers, and more. But not hospitals. Louisiana’s state legislature is not among those that have lately considered strengthening such rules.

Nothing in Louisiana’s law or regulations kicked in when Steward bought Glenwood Regional Medical Center in 2017, about four and a half years before Mearl Hodge ended up there with covid. Glenwood, Steward’s only Louisiana hospital, racked up 47 deficiency citations after Steward took it over, including four that were designated “immediate jeopardy.” Patients had started avoiding the hospital, according to local officials and former employees.21 Unpaid bills prompted vendors to cut off supplies needed to insert pacemakers and perform endoscopies, records show.22 One vendor cut off the coffee supply.23

Louisiana law allows penalties against hospitals that violate standards. In the months before the bankruptcy, state records24 show, the health department levied two fines, for $5,000 and $10,000, and said Glenwood would be banned from Medicare if conditions didn’t improve. The hospital promised improvements, and the department accepted the promises.

Hodge’s death came before those fines. Called Meme by her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, her obituary would say, Hodge was born and spent her life living in Farmerville, a town of 3,000 with a summertime watermelon festival, lying about 30 miles northwest of Glenwood. She loved to cook chicken and dressing and to share afternoon coffees with her friends and family, including her husband of 76 years. She prayed for her family daily.

As a one-time “class A” violation resulting in death or serious harm, and an “immediate jeopardy” deficiency, state law permitted a penalty up to $2,500 after Hodge’s death and the investigation. Yet even there, state regulation failed to tame an unruly health system.

On May 31, 2022, the state health department fined Glenwood the $1,750. Three months later, the department dispatched a second notice. The check Steward sent, the notice said, had bounced.

Methodology Appendix

-

How we did the data analysis for the Steward case study

To help us understand whether evidence existed before Steward Health Care’s 2024 bankruptcy that its nearly three-dozen hospitals were in trouble, we performed four data analyses. Each relied on a different type of data. Most of it was information that the federal government and—in some instances—states collect. Other information is contained in the records of Steward’s bankruptcy case in the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Texas.

Here is a description of each analysis.

-

Steward hospital finances

We analyzed four measures of hospitals’ financial condition, which we selected based on a review of academic research and work by hospital executives and state health officials. These metrics are among the ones most commonly used to indicate the condition of hospitals’ finances. The data are readily available, because virtually every acute care hospital that participates in Medicare is required to report them as part of an annual Medicare Cost Report submitted to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

The metrics are:

- Operating margin. Indicating a hospital’s ability to continue functioning, it is defined as excess operating revenue as a percentage of total operating revenue.

- Net profit margin. Another measure of a hospital’s profitability, it is not that different from operating margin, except that this one takes into account all forms of revenue, plus non-operating expenses, such as taxes and payments to shareholders.

- Current ratio. A way of understanding a hospital’s ability to cover its costs in the short term, it is defined as the ratio of “current” assets it could make liquid within a year to “current” debts that it owes within that year.

- Equity financing ratio. A way of understanding how dependent a hospital is on debt, it is defined as the proportion of a hospital’s net assets that it owns in full instead of being financed with debt.

These data come from three sources. One is the CMS Hospital Provider Cost Reports, published annually based on the cost reports compiled in the Healthcare Cost Report Information System (HCRIS). These data include information about revenues, costs, assets, and debts for every Medicare-certified institutional provider in the U.S. with data available from 2011 to 2022.25 We used these data to produce figures on the current ratio and the equity financing ratio. A second source is cost reports published in the National Academy of State Health Policy (NASHP) Hospital Cost Tool, which is also based on cost reports submitted by hospitals and compiled in the CMS HCRIS. These data include certain information about revenue and costs from 2011 to 2023. We used the NASHP data to produce figures on operating profit margin and net profit margin, but these data do not include metrics on hospitals’ assets and liabilities, so we did not have information for 2023 on the two ratios we analyzed. We confirmed that the data are consistent between NASHP and CMS for the years they overlap. Finally, we used audited financial statements for Steward that were collected by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and by the Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis. We used these financial statements to analyze performance on the health-system level for all the metrics we analyze from 2011 to 2021, excluding 2016.26

We made some data adjustments. In periods during which hospitals change the time frame for their fiscal year, the CMS data and NASHP data differ. For example, if a hospital’s fiscal year was July 2016 to June 2017 and it changes to January 2016 to December 2016, the data reported during 2016 is not consistent between the NASHP and CMS data. As a result, we eliminated just that year of data for any hospital that altered its fiscal year (so, for the example above, it would have missing data for 2016).27

With this financial data, we began by calculating an unweighted average each year for each metric among the hospitals that Steward owned.28 We considered a hospital to be owned by Steward starting the year it was acquired. We then calculated an unweighted average across all U.S. hospitals for all four metrics.29 Finally, we calculated these same metrics with the system-wide audited financial statements. Because the audited financial statements are at the system-level, these are weighted values.

-

Steward hospital quality

We analyzed four out of a variety of quality indicators that virtually all acute care U.S. hospitals report to CMS each year. To select measures for our analysis, we conferred with CMS officials and contractors, seeking their judgment about which metrics are the most telling reflection of the caliber of a hospital’s care, rather than primarily a mirror of external factors, such as the socioeconomic make-up of a hospital’s patient base. Using this criterion, we analyzed four measures:

- Complications. Composite rate of medical complications from all hospital services.

- Emergency department. Percentage of patients who left a hospital emergency department without being evaluated or treated by its staff.

- Pneumonia deaths. Percentage of deaths from pneumonia within 30 days of patients’ hospital discharge. Considered a better reflection of the quality of care than other mortality metrics, because patients sometimes acquire pneumonia as inpatients.

- Readmissions. Percentage of patients unexpectedly readmitted to a hospital within 30 days of their discharge.

For each of these measures, we analyzed data from 2010, the year the Steward system was created, through 2024. We obtained the data for this analysis from the Wayback Machine and CMS’s Care Compare website. Each year, CMS reports a score for each individual hospital and calculates a national score—both of which we used in our analysis.30

For each metric, we calculated the average score for each year among the hospitals owned by Steward and compared it with the average for all U.S. hospitals. Again, we considered a hospital to be owned by Steward starting the year in which it was acquired. In addition, we focused on the annual quality scores of five individual hospitals. We selected these because, in a different way, they appeared especially problem-ridden, and we were curious whether they appeared worse than the company-wide average. The five hospitals had the most deficiency citations (see explanation below) for the past five years, 2019 through 2024. The hospitals are Mountain Vista Medical Center (AZ), Glenwood Regional Medical Center (LA), Good Samaritan Medical Center (MA), The Medical Center of Southeast Texas (TX), and Wadley Regional Medical Center (TX).31

-

Lawsuits against Steward

To understand Steward’s apparent failure to pay some of its bills, we reviewed lawsuits filed against the company and its hospitals by vendors. To identify lawsuits for this analysis, we relied on two sources of civil suits categorized as breach of contract—all of which alleged nonpayment. One source is in the records for the Chapter 11 bankruptcy case Steward filed in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Texas. A document that is an amendment to the “Statement of Financial Affairs for Non-individual Steward Health Care System LLC,” includes all vendors that had a breach of contract lawsuit against Steward alleging unpaid bills that remained unresolved within a year of the bankruptcy filing, May 6, 2024. The other source is a list of lawsuits from LexisNexis’s CourtLink database. For those identified via CourtLink, we filtered for breach-of-contract cases in which Steward is the defendant. From these two sources, we identified 152 relevant cases. This sample is almost certainly an undercount, because some cases are too old to have been listed in the bankruptcy document, while some local circuit and district court dockets are not included in the CourtLink database.

For as many of the 152 cases as possible, we collected the original complaint in which the plaintiff describes the alleged breach of contract. For about 16 cases, the information in the bankruptcy docket’s document was insufficient to identify a case number, so we were unable to locate the original complaint. For nearly 10 additional cases, the complaint was not publicly available or could be retrieved only in person at a distant courthouse. In the end, we read the original complaints in 127 cases. And, from the description in each one, we collected and analyzed the service provided, when the vendor began working for the company, when nonpayment was alleged to have begun, when the lawsuit was filed, and the amount Steward allegedly owed.

-

Hospital deficiencies

As another way of understanding Steward hospitals’ quality, we focused on records involving deficiency citations. These are public records that follow complaints accusing a hospital of poor care, filed by patients, relatives, or staff members. Such complaints are lodged with an agency in each state, designated by CMS to conduct an investigation, known as a survey, that confirms a problem—that is, a deficiency—or finds a complaint unwarranted. If a deficiency exists, the agency requires the hospital to submit a plan to correct the flaw. CMS has defined three levels of deficiency citations, depending on their severity: standard, condition, and immediate jeopardy. An immediate jeopardy citation involves an instance in which a patient died or was injured, or easily could have been. The records specify each deficiency’s level of severity.

For our deficiency analysis, we obtained from CMS a nationwide spreadsheet of hospital deficiencies through most of 2024, months after the company declared bankruptcy, and we then extracted from it the cases involving hospitals during the time they were owned by Steward. We identified hospitals as owned by Steward based on both the year and month that the hospital was acquired by the company. We also obtained records from four state health agencies—in Louisiana, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Utah. The state records contained deficiency citations, plus, where they existed, records of fines that the state levied against a Steward hospital found to have an immediate jeopardy citation. The federal government does not have the authority to financially punish hospitals for deficiencies, but some states do. The records contained 678 unique deficiencies for the Steward hospitals.32 We analyzed them by level of severity and year, and we examined the narrative description of immediate jeopardy cases to understand what they entailed and which ones led to penalties.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors thank Richard Frank for indispensable consultation throughout this case study. He and Loren Adler provided useful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. The authors also thank members of the Brookings Institution staff for their excellent contributions: Austin Grattan, Preethi Subbiah, and Amaya Allen for their research help; Yihan Shi and Chloe Zilkha for editorial assistance, Rasa Siniakovas and Chris Miller for web posting expertise.

This case study was supported by Cathy E. Minehan, a trustee of the Brookings Institution.

-

Footnotes

- Authors’ review of deficiency report by Louisiana Department of Health.

- Authors’ review of sanction documents, Louisiana Department of Health.

- See methodology appendix for details.

- Unweighted average for Steward hospitals and all U.S. hospitals.

- In Steward’s case, audited, system-wide financial statements were required by the Massachusetts attorney general as part of monitoring the company’s initial five years. And once Medical Properties Trust was involved, that real estate company was required to report audited financial statements to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

- From interviews with two former senior Steward administrators, who spoke for this case study on the condition of anonymity.

- Conversations with several health care finance specialists, including Nancy Kane.

- Authors’ research into the 10 states’ transparency policies.

- Unweighted average for the individual hospitals and for U.S. hospitals nationwide.

- Authors’ analysis of lawsuit original complaints.

- Original complaint within the bankruptcy docket.

- Authors’ analysis of the deficiency data and total count of hospitals.

- From Excel spreadsheet of hospital deficiency citations provided to Brookings by CMS Center for Clinical Standards and Quality, Quality, Safety, and Oversight group.

- Authors’ conversations with staff at these two health departments.

- Interviews with current and former state officials and hospital representatives.

- Review of Steward Health Care System LLC v. Center for Health Information and Analysis; Case No. 1784CV03481, Massachusetts Superior Court, Suffolk County.

- Review of Steward Health Care System LLC v. Center for Health Information and Analysis; Case No. 1784CV03481, Massachusetts Superior Court, Suffolk County.

- In theory, hospital accrediting organizations already play a role, but their work is mainly not public, and there is no indication they ever stripped Steward hospitals of their accreditation.

- Conversations with Sen. Markey’s staff.

- Conversations with Sen. Murphy’s staff.

- Conversations for this case study.

- Deficiency report from Feb. 5, 2025, survey by Louisiana Department of Health.

- Conversation with community for this case study.

- Records of sanctions, February 5, 2024, and April 15, 2024, Louisiana Department of Health.

- Occasionally, during our study period, a hospital’s fiscal year will change affecting its financial reporting. We drop the years in which a fiscal change occurs.

- Steward never produced a financial statement that was formally audited in 2016.

- Easton Hospital (PA) experienced a fiscal year change in 2016 and then was acquired in 2017 making the NASHP and CMS data inconsistent for both years, as a result, we dropped both 2016 and 2017 for Easton specifically.

- In this analysis, we excluded six Steward hospitals that, for various reasons, do not report their own financial data to CMS. These half-dozen hospitals were Abrazo Mesa Hospital (AZ), Luke’s Behavioral Health Center (AZ), Florida Medical Center (FL), New England Sinai Hospital (MA), Hillside Rehabilitation Hospital (OH), and Mountain Point Medical Center (UT).

- To remove extreme outliers, we excluded the bottom and top 1% of the distribution for each metric when calculating the average.

- The same six hospitals that we excluded from the financial analysis because they do not submit financial data were also not included in the quality analysis because they are not required to submit CMS hospital compare data.

- St. Lukes Behavioral Health Center also had a high number of deficiency citations in the past five years. Because it is not an acute care hospital, it does not report quality data and could not be included in the individual hospital analysis.

- This includes one immediate jeopardy case provided to us in records from Louisiana that initially was not included in the federal database.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).