This week in Dubai, Israel, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) signed Israel and Jordan’s biggest energy and water deal since the neighbors made peace 27 years ago. If implemented, this will be a diplomatically transformative deal for a region facing some of the worst consequences of climate change, as noted by U.S. Climate Envoy John Kerry, who was also present at the signing. While the scope is very modest in terms of global mitigation of climate change, it will have a huge impact on Jordan’s effort at climate adaptation.

The deal is the product of intense three-way negotiations. The idea was initially proposed by EcoPeace Middle East, an Israeli-Jordanian-Palestinian non-governmental organization, which outlined a desalinated water-energy community between Israel, Jordan, and Palestine as part of a proposal called a “Green Blue Deal for the Middle East.” (The Palestinian director of EcoPeace discussed water security at a Brookings conference, “The Middle East and the New U.S. Administration,” in February 2021).

The normalization of relations between Israel and the UAE was part of the Abraham Accords in August 2020. These agreements allowed for Israeli-Emirati negotiations to take place and for Emirati funding and technical know-how to be involved via an Emirati government-owned firm, Masdar. This company would construct a large solar power facility in Jordan, which would produce electricity by 2026. All the electricity produced would be sold to Israel for $180 million dollars per year, contributing, modestly, to Israel’s goals for increasing its renewable energy and diversifying its energy sources that primarily include large reservoirs of natural gas in the Israeli exclusive economic waters. Masdar, the Emirati company, would split the proceeds with Jordan. In return, Israel has committed to provide desalinated water from its Mediterranean coast, perhaps via a new separate desalination facility, to produce 200 million cubic meters of water for Jordan, in a significant boon to Jordan’s water supply.

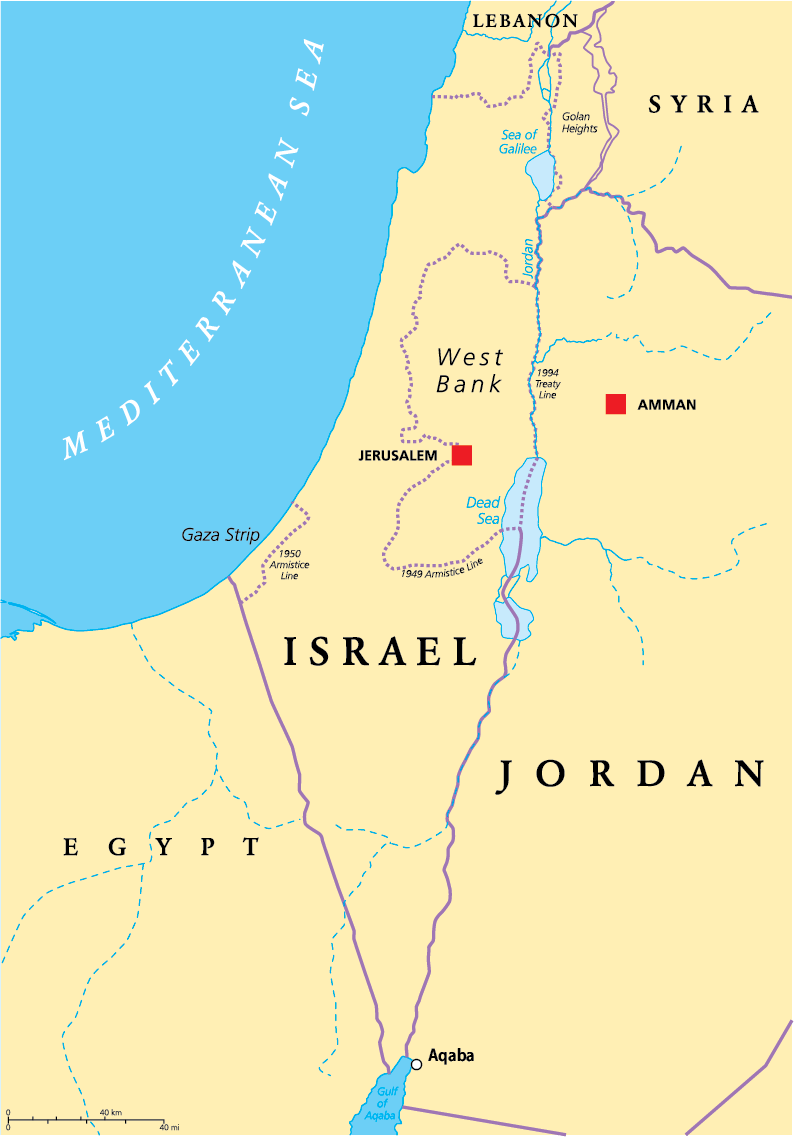

Israel, itself water-poor, began desalination of sea water starting in 2005. Since then it has dramatically increased desalination capacity to now provide for most of Israel’s water needs. The state’s latest plans call for perhaps 90% of Israeli municipal and industrial consumption to come from desalinated water. Although energy-intensive, desalination solved a long-standing shortage in the Israeli water supply. Importing water from Israel is more efficient for Amman than developing its own desalination capabilities since Jordan’s small Red Sea coastline at Aqaba, in the south, is far from the Jordanian population centers. Israel’s Mediterranean coastline, to their west, is the natural source of sea water.

Israel and Jordan have been in a cold peace for most of the last quarter century. Then-Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu alienated Jordanian King Hussein in 1997 by sending assassins into Amman to kill a Hamas leader, Khaled Mishal. The job was botched, and the assassins caught by the Jordanians, to be released only in return for a life-saving treatment for Mashal and the release from Israeli prison of Hamas founder, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin. The king called then U.S. President Bill Clinton in a fury. As Clinton was in a meeting, one of us (Riedel) took the first call and listened as the king slammed the Israelis for trying to poison Mashal on the street in Amman only three years after the treaty was signed. The relationship went downhill from there. Hussein’s successor, King Abdullah II, similarly had a cool relationship with Netanyahu and had not met with him in the past few years.

The first sign of better times in the relationship came in July 2021, when Israel’s new prime minister, Naftali Bennett, traveled to Amman for a secret meeting with the king. Shortly after, the two countries announced that Israel would double the amount of desalinated water it sells to water-strapped Jordan. The new Israeli-Jordanian-Emirati project would quadruple the amount agreed upon in July.

This deal, if it materialized, would set a new bar for Israeli-Jordanian civilian cooperation. The countries have already cooperated on gas infrastructure, with the sale of Israeli natural gas to Jordan. They even reached a tentative agreement for a hydro-electric project running sea water from the Red Sea (at sea level) to the Dead Sea, at -400 meters — the Red-Dead project. The agreement never came to fruition, however, due to Israeli misgivings on the utility of the project and public concern over its effects on the Dead Sea. None of the prior agreements, however, would have had this effect in real terms, especially in water supply to Jordan.

Emirati Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayid deserves much of the credit for the solar-water plan. His recognition of Israel last year set the stage for a rash of dealmaking. His accord also removed the threat of Israeli annexation of parts of the West Bank, initially including the Jordan River Valley, as presaged in the Trump administration’s so-called deal of the century plan. Had Israel annexed the valley, King Abdullah may have suspended at least parts, if not all, of the peace treaty with Israel.

Israel has its longest border with Jordan, two hundred miles north to south, one that has been remarkably stable and quiet for decades since the Jordanian civil war in 1970. The economic and environmental potential of cross-border cooperation is now being realized on a large scale, a major advance for green power and climate change policy in the region, which is already on the cusp of climate crisis.

King Abdullah will be careful in selling the deal to Jordanian public. The peace treaty is very unpopular in Jordan. Polls show the public is strongly against it and Jordanians regard Israel as the number one threat to their country. Nonetheless, easing Jordan’s water shortage is a strategic imperative for the Kingdom, and the deal with Israel is a natural and elegant part of the solution. As with water-supply deals in the past, there will likely be rhetorical opposition, but unless there is physical sabotage to the project, it will likely not be stopped by domestic politics.

Absent from the deal so far is the third component EcoPeace proposed — a Palestinian angle. So far, the Palestinian Authority has stayed away from most aspects of the Abraham Accords, viewing them as an attempt to sidestep the Palestinians and force them to compromise on their own interests. Including the West Bank in a future iteration of the deal would make sense for all parties involved.

Good news is a rare commodity in the Middle East. So is practical progress on climate change.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Israel, Jordan, and the UAE’s energy deal is good news

November 23, 2021