Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

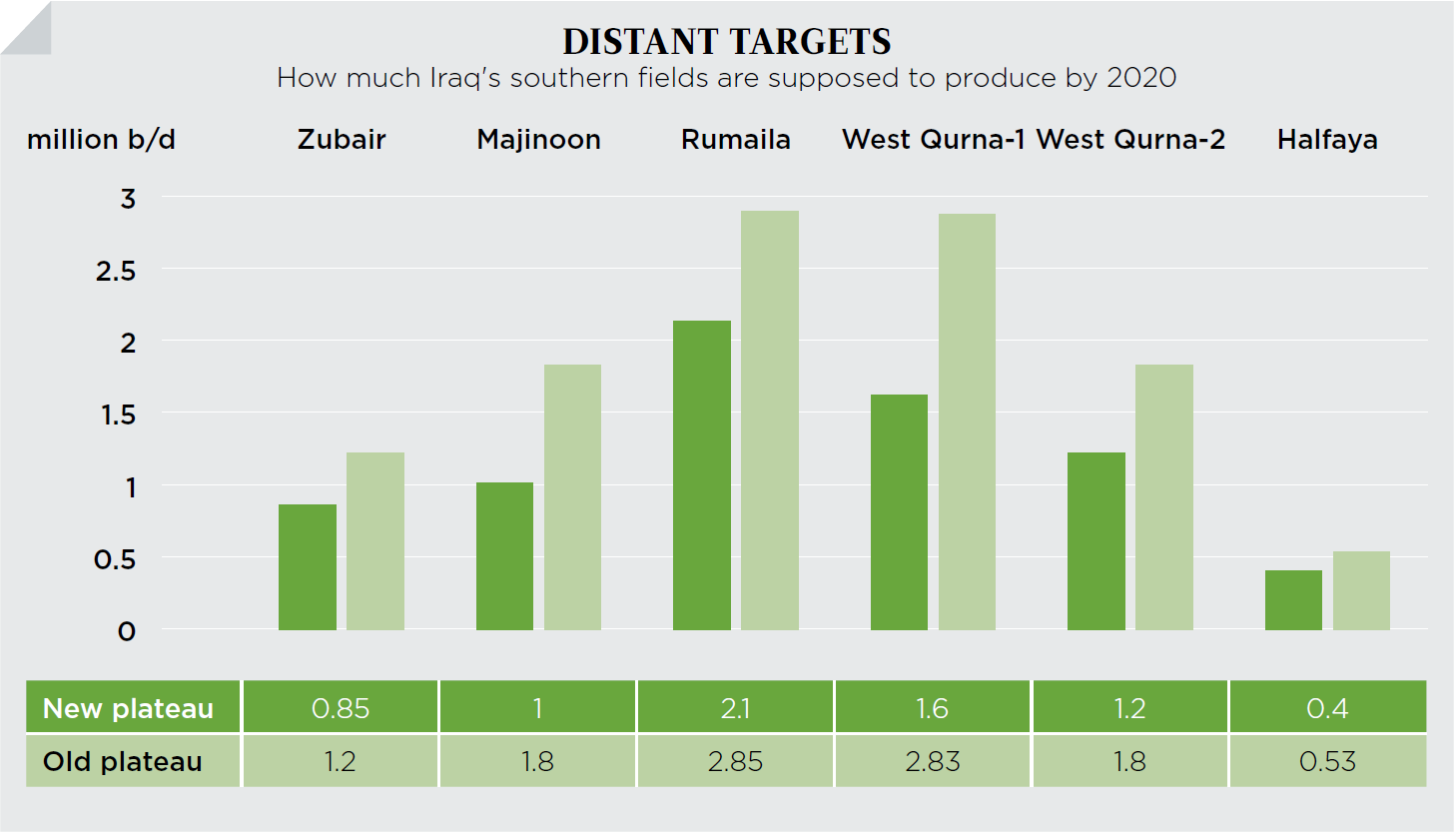

Since 2003, Iraq’s policy-makers had taken the optimistic view –high oil prices were here to stay and the international oil companies contracted to develop the country’s huge southern oilfields would meet their plateau targets, originally around 12 million barrels a day by 2017. It is clear now that they didn’t see the serious commercial and technical difficulties in front of them, or rightly forecast the outcome of domestic politics and regional dynamics.

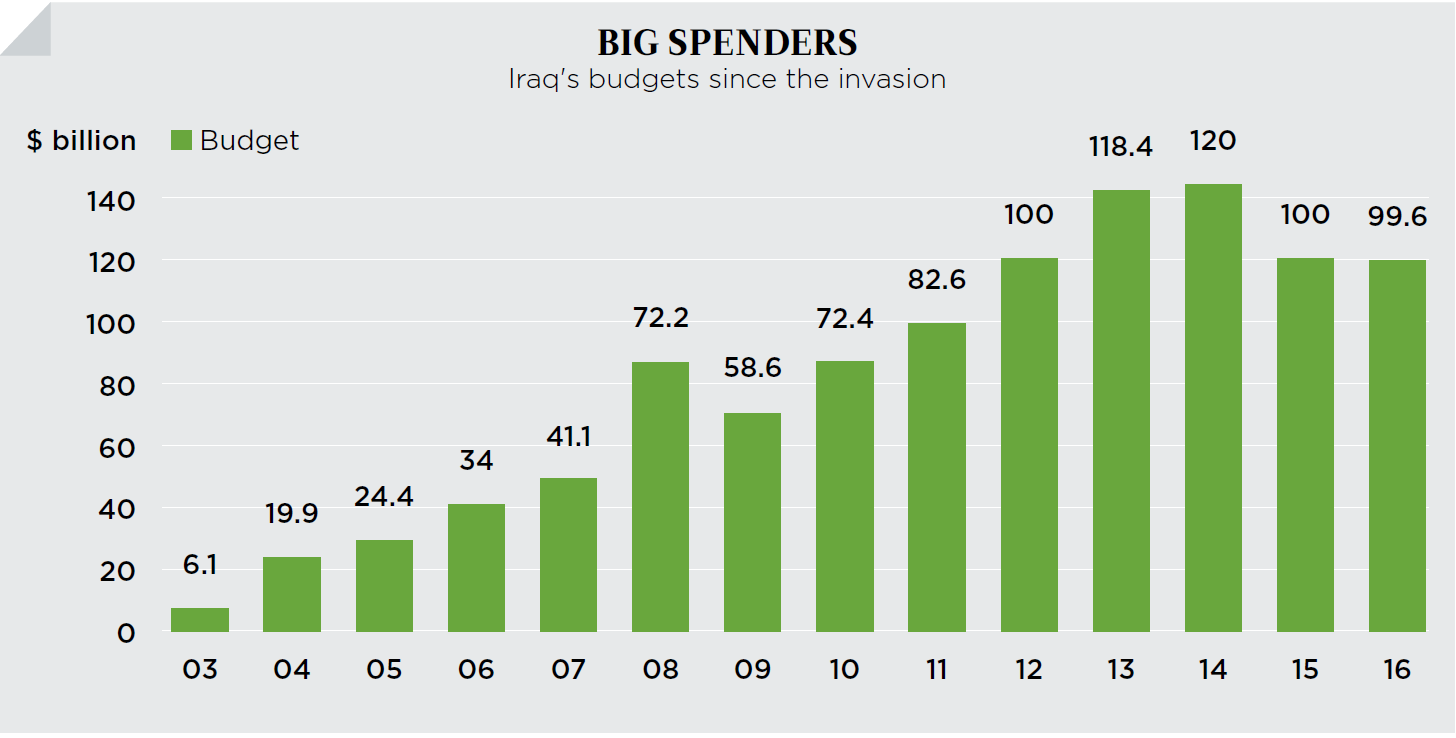

The budget for 2016, which Iraq’s Ministry of Finance proposed in mid-September 2015, recognized some of what has taken place over the past year, but was still rife with optimism. The $99.6 billion budget, which includes deficit spending of $25.8 billion, assumes a $45-a-barrel oil price, and the seamless continuation of a December 2014 deal with the Kurdistan Regional Government over oil revenues. This arrangement depends on the KRG sending 550,000 b/d to the State Oil Marketing Organisation: 300,000 b/d from Kirkuk oilfields and 250,000 b/d from KRG-controlled fields.

Oil exports for 2016, believes the ministry, will be 3.6 million b/d including 3.05 million from the south. That looks feasible – but getting $45/b is rather ambitious. The market is glutted, and as 2016 begins so will Iranian oil exports –not to mention the sale of that country’s 36 million barrels or so of floating stored oil. Iraq, like other Opec members, will offer discounts to maintain market share, thereby reducing the chances of keeping prices above $40/b in 2016. It’s probably better to assume Iraq will garner $35/b for its oil next year – making 2016 difficult for a country needing $101/b to keep its budget afloat.

This will add to the many financial challenges Iraq already faces, given the costly war with the so-called Islamic State and the difficult task of managing 3.5 million internally displaced people.

The oil-price slump and rising imports have already seen the Central Bank of Iraq’s foreign-currency reserves shrink from $78 billion at the end of 2013 to around $59 billion in mid-2015. The Iraqi Dinar also fell sharply.

The situation would be worse if it weren’t for relatively strong production growth in recent years. Since 2010, Iraq’s crude oil production has grown 2 million b/d and reached 4.4 million in the third quarter of 2015. Present capacity includes 3.7 million b/d controlled by the federal Ministry of Oil and 700,000 controlled by the KRG’s Ministry of Natural Resources. Despite the loss of the 220,000 b/d Baiji refinery, a casualty of the war with IS, Iraq’s total consumption (including Kurdish Iraq) has exceeded 800,000 b/d, leaving around 3.6 million for export. This includes 3.1 million b/d handled by Somo and 500,000 b/d marketed independently by the Kurdish MNR.

The 2016 forecast calls for the MoO and Kurdish MNR to add around 500,000 b/d of new oil, mostly coming from Kurdish Iraq (300,000 b/d). Yet Baghdad and Erbil are facing significant financial and technical challenges that, if not resolved, could not only scupper this outlook, but reduce capacity by 10%.

IOCs in the south are seeking $9 billion in payments by the end of 2015 to cover reimbursements up to the third quarter of the year (with Q4 payments deferred to 2016). Despite government demands that IOCs reduce their expenditure, the economics of the technical-service contracts signed by these investors are unlikely to change. IOC entitlement for 2016 could therefore reach $12 billion. To pay it, the government may be forced to issue external bonds – or lose its ability to finance IOC operations in the south.

IOCs operating in Kurdish Iraq have been less fortunate. The payments owed to them by the MNR continue to mount – the balance in Q3 2015 was around $3.5 billion. The outstanding sum will grow, too, because Kurdish oil revenues are barely covering provincial budgets, while the cost of its war effort against IS continues to rise.

This financial strain further exacerbates the political dispute between Baghdad and Erbil over oil-export rights and the issue of how much money is due to the KRG from the federal government. To keep oil exports flowing out and revenue coming in, the KRG is under pressure to offer heavily discounted rates to international markets and manage sales opaquely – a practice that further complicates domestic politics.

Worse still, many experts believe that the MNR and MoO’s production forecasts for 2016, and beyond, are a pipedream. Various commercial, financial and technical reasons justify the skepticism.

In the south, infrastructure projects are facing significant delays, which could impede development. Export network and storage capacity are insufficient, no progress has been made on water-injection projects, volumes of associated-gas flaring have doubled to 1.6 billion cubic feet per day, and IOCs are frustrated about delayed repayments.

The flaw of the TSCs is that Iraq has to pay back the operational cost and IOC remunerations within one quarter – it means the IOCs are not really investors; at best they provide short-term working capital.

In the North, a cash-crunch is stopping further investment by the IOCs. DNO and Genel are chasing the MNR for nearly $1.5 billion owed to them for work already done; the MNR is facing multi-billion dollar claims for unpaid invoices and damages having already lost the liability phase of the arbitration against the Dana Gas consortium; and Afren and others have given up their blocks in Kurdistan altogether. Added to the KRG’s problems are the recent oil theft and sabotage on their only oil-export pipeline – the financial lifeblood of the region and the source of its funds to fight IS. The KRG needs around $8 billion a year just to pay local salaries, let alone the cost of the war and public services.

Given the achievements of the past five years in raising oil output, it is possible Iraq will add another 2 million b/d of production by 2020 – mostly from southern fields, but with about 500,000b/d from Kurdish fields. However, that’s a medium-term view. The short-term outlook is fraught with much greater difficulties.Unless the MNR and MoO overcome their problems quickly, output in 2016 will probably remain at around the level seen in the third quarter of 2015.

This will make the longer-term outlook less rosy. Persistent low oil prices, the war on terror, 3.5 million internal refugees to manage, out-of-control public spending and increasing debts to IOCs make it doubtful Iraq will come close to reaching its 7.1 million b/d revised production target by 2020. It’s not impossible– but the goal looks a long way off from here.

This article originally appeared in Petroleum Economist Outlook 2016.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Iraq 2016 outlook: Reality bites

November 25, 2015