Iranians will go to the polls on Friday to choose new representatives for two important governing bodies: the parliament (Majlis-e shoura-ye eslami) and the Assembly of Experts (Majlis-e Khobregan). Perhaps surprisingly, given the Islamic Republic’s track record for domestic repression, elections are a regular feature of Iranian politics. Friday’s ballot marks the 33rd time that Iranians have participated in national elections in the Islamic Republic’s 37-year history. Reviewing this history highlights several important trends that provide insight into what may happen on Friday.

Who runs?

What ultimately shapes Iranian electoral outcomes is their input—the candidate pool. Iranian elections are highly controlled; prospective candidates are reviewed by the Guardians’ Council, a small but powerful clerical institution that is empowered to review parliamentary legislation, interpret the constitution, and supervise elections. Its approach to election supervision has expanded considerably as a result of the competition for influence among the regime’s elites.

Candidate screening was part of the revolutionary system from the start. However, in the late 1980s, in the aftermath of the eight-year war and the death of the revolution’s charismatic founder, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the Guardians’ Council assumed a more stringent scrutiny over aspiring candidates for both the Assembly of Experts and the parliament, or Majlis. In his two terms as president, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani strongly supported this shift, in hopes of diminishing the influence of leftist members of parliament who had opposed his efforts to spearhead post-war reconstruction. As with many episodes of Iranian politics, Rafsanjani’s gambit came back to haunt him, and he himself was disqualified by the Guardians’ Council for the 2013 presidential race.

The aggressive vetting of candidates on the basis of factional preferences has forced movements like Iran’s reformist front to engage in creative tactics, such as expanding the pool of prospective candidates in hopes of overwhelming the review process and supporting a cross-factional list that includes candidates from Iran’s moderate camp. This is one of the reasons for the steady increase in applicants to run for office. As the list of registered candidates grew late last year, some observers suggested that reformist forces were hoping to flood the system, assuming that the Guardians’ Council would not disqualify all of their candidates.

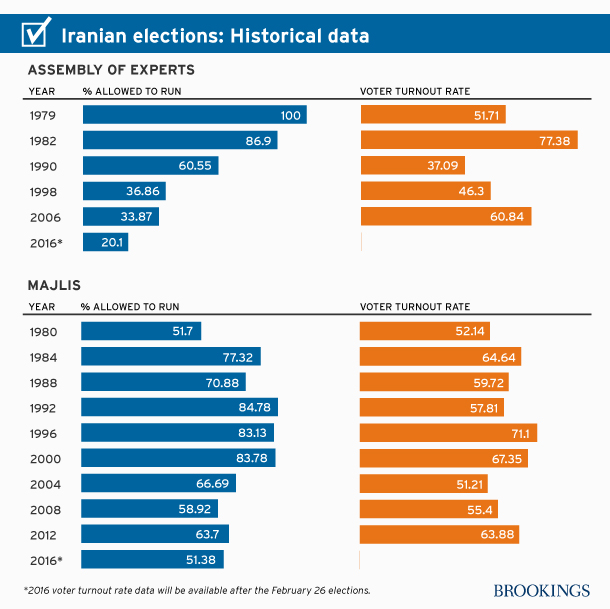

For the upcoming vote, applications for both ballots reached record highs—the pool of candidates for the Majlis elections more than doubled since 2012. At the same time, however, the percentage of those approved to run plummeted to record lows. Only 51.4 percent of Majlis candidates were approved (6,229 out of 12,123), the lowest rate of approval for these elections ever. The closest parallel was the 51.7 percent approval rate in the Islamic Republic’s first Majlis election in 1980, when an open power struggle raged among the various groups within the revolutionary coalition.

The contest for the Assembly of Experts has experienced similar trends. Just over 20 percent of aspiring candidates were approved to run in the Assembly of Experts election (161 out of 801), also the lowest rate in the history of these elections. The second lowest rate of approval for Assembly elections, 33.9 percent, was in 2006. The Assembly’s current membership also blocked efforts by Iran’s executive branch to expand the overall size of the body in accordance with Iranian law to account for dramatic population growth in the country since its original establishment.

The small pool of candidates for the Assembly effectively means that a sizeable proportion of candidates find themselves uncontested and may take their seats on the Assembly by default. (Note: some Iranian press reports suggest that officials have taken steps to mitigate this issue, but there is no indication of additional candidates approved to run.)

The relatively modest size of the race also has heightened the media focus, both within Iran and abroad, on the prospects for high-profile candidates from competitive districts. This explains, in part at least, why the disqualification of Hassan Khomeini (the grandson of the Islamic Republic’s first supreme leader) provoked such controversy. He was seen as a well-known name who might provide a new standard-bearer for the embattled reformists. In his absence, reformists have sought to make common cause with more moderate factions, and are focusing their efforts instead on blocking three prominent hardline clerics from re-election to the Assembly. President Hassan Rouhani and former president Rafsanjani, both of whom are considered moderates, have been approved to run.

Who votes?

It’s difficult to predict participation in Iranian elections. History suggests only limited correlation between candidacy approval rates and voter turnout rates in either vote.

Iran’s leaders—most notably Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and President Rouhani—tend to associate electoral participation with regime legitimacy. For that reason, they have been encouraging voters to turn out in the February 26 elections, including via text messages sent under the president’s name. Earlier this month, Khamenei stressed that “[voter] participation in this huge event is an obligation for all people.” On the February 11 anniversary of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, Rouhani spoke of the ballot box as “the right of the people.” Even former president Mohammad Khatami, whose perceived sympathies with opposition protests in 2009 has led to his official marginalization since that time, issued a video encouraging Iranians to go to the polls.

It’s equally difficult to assess the credibility of voter turnout figures, since Iranian ballots have no independent monitors. (Perhaps in an effort to bolster credibility, Iran’s Culture Ministry is boasting that reporters from 29 countries will be covering the elections.) In the past, voter turnout rates announced by the Ministry of Interior have been misleading. In 2012, raw turnout numbers and percentages did not add up, and the numbers were announced over a week after elections. Voter turnout was particularly important to the regime that year, since demonstrations following former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s reelection in 2009 took a toll on the regime’s legitimacy.

Out with the clerics, in with the vets

Recent Iranian history demonstrates a distinctive shift in the composition of the parliament itself. In the wake of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, clerics comprised about half of the Majlis’ members. Over time, that number has declined dramatically. Today, they make up just over ten percent. Iran analyst Yasmin Alem suggests that the drop reflects the waning of revolutionary zeal that galvanized Iran in the late 1970s, and with it an attenuation in the popularity and perceived moral superiority of clerics. Although their numbers are waning in the Majlis, clerics retain their hold on key leadership institutions, including the Guardians’ Council, the Assembly of Experts, and of course the office of the supreme leader itself.

As the number of clerics in the Majlis has decreased, the number of technocrats has grown steadily. All new Iranian members of parliament (MPs) are required to hold an advanced degree; and the number of MPs with experience in the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) has also increased. Although Majlis members with IRGC experience sat in every parliament, until 2004 their numbers were in the single digits. That year, helped in part by the disqualification of many reformists who were incumbent MPs, at least 16 percent of the seats were won by IRGC veterans. Those numbers have continued to rise. Ali Larijani, who has served as speaker of parliament since 2008, served in the Guard during the Iran-Iraq war.

IRGC veterans tend to advocate a hardline stance on foreign policy issues, and in the seventh Majlis (2004 to 2008) they helped steer significant economic opportunities toward Guard-affiliated companies and away from foreign and private investors. On the whole, however, they do not represent a distinct voting bloc on the array of other issues that come before the parliament for debate. For example, Larijani advocated for parliamentary approval of the July 2015 nuclear deal, which some hardline forces opposed. The increased presence of former IRGC members in the Majlis renders the body less likely to investigate issues related to the IRGC or the supreme leader.

Where are the women?

According to U.N. data from 2015, women make up about half of Iran’s population. However, no women have ever been permitted to serve in the Assembly of Experts and there are only nine female members of the current Majlis (three percent).

Earlier this month, each of the sixteen women who registered to run in the Assembly of Experts election was barred from doing so.

A total of 586 women were approved to run in the Majlis election. In fact, this is the third largest number of women who have sought to contest Iran’s parliamentary ballot—the 2004 election drew a record 827 female applicants out of 8,172 total applicants—and a campaign called “transforming the male-dominated image of Majlis” has emerged. Some who are involved in the campaign urge support for male candidates who seek to make the Majlis more reflective of the population, at least in terms of gender. Even so, observers and voters alike know that the tenth parliament will not accurately reflect the diversity of Iran’s demographics and opinions.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Iran’s Guardians’ Council has approved a record-low percentage of candidates. What will that mean for the upcoming vote?

February 24, 2016