We all want our children to be successful. Unfortunately, for many lower-income children in the United States there is little likelihood of someday reaching the middle class. Our country’s level of social mobility has remained stagnant for decades, and on many measures, we lag far behind our European peers. New research from Stanford University has shown that our situation may be even worse than previously understood.

Clearly, we must improve the rate at which children born into low-income families are able to make it into the middle class. How should we do this? One of the most effective ways would be to “intervene early and often,” and devote more resources to programs for young children.

The federal government currently provides around 40 percent of total public outlays in programs for children. But political dysfunction in Washington and long-term federal budgetary trends are making it increasingly clear that state and local governments will bear greater responsibility for investments in children in the near future.

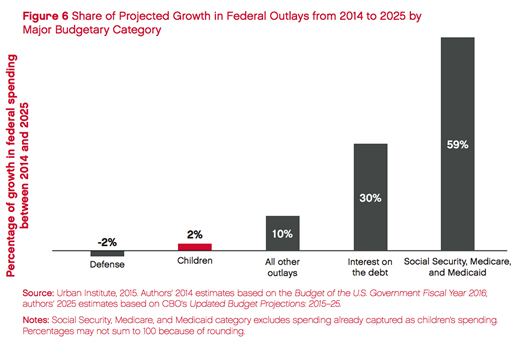

As detailed by the Urban Institute’s “2015 Kids’ Share Report,” federal spending is projected to increase by about $1.5 trillion over the next decade, but only 2 percent of that budget growth will go to children. Even that miniscule increase is deceiving—health care programs for children will be wholly responsible for the 2 percent bump. Spending on K-12 education, early education and care, refundable tax credits for children, housing, and nutrition is projected to decline by 25 percent or more in the next decade as a percentage of GDP. Unbelievably, excluding children’s health care spending, fewer dollars will be spent on children in 2025 than in 2014, after adjusting for inflation. As the authors of the report conclude, “relative to other outlays and uses of our national income, children are scheduled to become an ever-declining priority.”

This does not mean that the rest of our nation can afford to spend less on our youth. According to UNICEF, the United States currently ranks 28th in relative child poverty rates, 26th in preschool enrollment and 23rd in youth participation in education, employment, or training. Overall, we rank 26th in a composite measure of child well-being, in the neighborhood of Greece, Lithuania, Latvia, and Romania.

In order to do better, cities and states will have to find ways to increase investments in children without the help of the federal government.

Already, a number of cities and states have stepped up. Salt Lake County used social impact bonds to expand high-quality preschool to low-income neighborhoods. New York City partnered with state government in Albany to increase access to pre-kindergarten throughout the five boroughs. San Antonio funded universal pre-k through a voter-approved tax increase. West Sacramento combined public, private, and civic sector funds to expand access to preschool. Delaware recently doubled the public funding of its Nurse-Family Partnership program, which provides pairs new, low-income mothers with registered nurses. Many other places have expanded programs promoting childhood well-being without assistance from Washington.

These types of programs aren’t just the right thing to do—they are excellent investments. Tim Bartik of the Upjohn Institute has estimated a five-to-one benefit-to-cost ratio for high-quality preschool and a one-and-a-half-to-one ratio for high-quality childcare, pre-kindergarten, and programs like the Nurse-Family Partnership. For many cities, the issue is finding the initial funding for these programs, leading many to seek the support of the private and civic sector.

The fact that some places have been able to successfully invest in children does not mean that decreasing federal support is a good thing for our nation. Assuming there is no radical change in the federal trajectory, outcomes will begin to vary more dramatically from place to place. Certain states and cities will be able to raise revenue for things like universal Pre-K, better schools, and home visits for low-income parents, while others will not. This will have major implications on intergenerational equity in places that are already struggling.

How can Washington be helpful as it decreases its investments in children? At the very least, it could give cities and states more flexibility in how federal resources are used, allowing them to align federal funds with their distinctive needs. Federal grants are often too prescriptive and too narrowly defined to address the complex and highly varying challenges that different metros face. More flexibility would also strengthen local and state governments’ hands in leveraging capital from the private and civic sector.

Despite what presidential candidates have been promising, the investments that will drive our country forward in the 21st century will increasingly come from state and local actors. The federal government would do well to recognize this—and states and cities had better be ready.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Investing in children: Cities and states are now in charge

October 29, 2015