Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

The Pre-Summit Backdrop

Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) have been among the most contentious economic issues in the bilateral relationship between India and the United States. For several years, the U.S. has claimed that the Indian regulatory regime has been both weak and inadequately enforced. In a number of IPR domains, the contention has been that U.S. business interests are being harmed by unfair use of IPR on the part of Indian businesses. In its Special 301 Report for 2014, the Office of the United State Trade Representative (USTR) put India on its priority watch list and scheduled an Out-of-Cycle Review (OCR) for the fall of 2014.

India’s position on this issue was that all IPR-related laws and regulations were entirely compliant with World Trade Organization (WTO) norms. India had taken many significant steps to amend its patent laws based on WTO norms. Consequently, the U.S. position that the regime be further changed so as to accommodate specific U.S. interests brought an unnecessary bilateral dimension to what was essentially a global rulebook, which both countries had signed on to. The OCR process was a provocation because it carried the threat of sanctions based on the recommendations of the report.

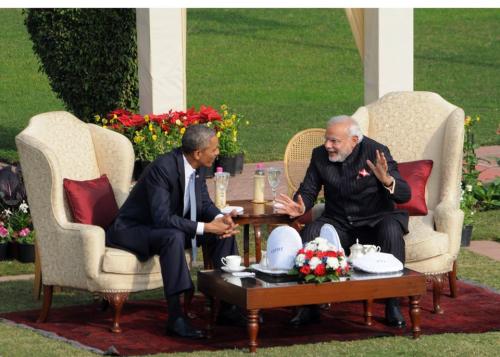

In short, the two countries went into the first summit between President Barack Obama and Prime Minister Narendra Modi in September 2014 in relatively antagonistic positions on this issue.

The September 2014 Summit and After

The summit clearly brought the two countries together on a whole range of issues. The joint declaration was seen as being highly co-operative and making a substantial statement on bilateral relations. It proposed concrete steps on a variety of fronts. On IPR, the declaration proposed the setting up of a high-level joint working group that would address the points of contention between the two sides. With this announcement, a potentially damaging stand-off was averted. Subsequent developments on both sides suggest that a number of convergent steps have been taken, consistent with the intent to seek co-operative rather than adversarial solutions.

On the Indian side, the Ministry of Commerce announced the setting up of a think tank on IPR issues. Chaired by a former judge, the mandate for this group was to review the entire existing framework and recommend changes that made it more relevant to the contemporary knowledge and technology context. The announcement did not specifically refer to the issues pending in the bilateral India-U.S. context. It emphasized a larger and very significant motivation: the need to stimulate and incentivize innovation in India. In effect, it opened up the question of whether the current regime was serving India’s own interests; any resolution of bilateral issues through recommended changes would essentially be collateral benefits. This was an important signal that the government is open to reviewing policy positions in an evolving economic environment. The added tangential benefit was the clear signal that the government was moving ahead in the spirit of the joint declaration. The final report of the group was expected in December 2014. However, it has not yet been made public.

On the U.S. side, the OCR was initiated in October, as per schedule. The report is not yet available on the USTR website. However, in mid-December, media reports indicated that the review had been concluded and that the broad assessment was that India had taken sufficient steps on a range of contentious issues. A report in the Business Standard of December 15, 2014 quotes the USTR report as lauding India’s efforts for having a “meaningful, sustained and effective” dialogue on IPR issues. The story quoted a top U.S. official anonymously saying that the new government has taken some “baby steps towards improving the country’s weak IPR laws”.

An opportunity for face-to-face articulation of the post-summit positions was provided in November during the meeting of the India-U.S. Trade Policy Forum. The joint statement put out after the forum mentions co-operation on a variety of fronts – copyright issues, the leveraging of traditional medicine for affordable health care and the protection of trade secrets. It reinforces India’s commitment to an innovation-friendly IPR regime and records the United States’ agreement to support this process and share information.

In his speech delivered at an event organized by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) on the occasion of the Forum, Ambassador Michael Froman, USTR, also projected a positive U.S. view on India’s steps towards reforming its IPR regime. He said that addressing patents, copyrights, trade secrets, piracy and so on were all critical to an effective IPR regime and that the U.S. had “great interest in the ongoing review of India’s Intellectual Property Rights Policy”.

Assessment and Next Steps

In sum, all the post-summit developments described above suggest that both countries have begun a process of convergence towards some mutually acceptable middle ground. From the Indian perspective, it was important that any review of the current regime be seen as being motivated by national interests and not by pressure from the United States. This seems to have been accomplished and legitimately so. On many issues, piracy for instance, the interests of Indian producers are also adversely affected by regulatory lacunae and weak enforcement. The premise that the weaknesses in the current regime may be hindering innovation and creativity of domestic producers is entirely defensible. While audio and video piracy may be vivid examples of this, the fact is that it puts the entire range of innovative activity at risk.

From the U.S. perspective, the comments by Ambassador Froman and the stated tone of the OCR report suggest that India’s efforts to initiate reforms in its IPR policy framework have significantly eased concerns. The expressions of support for the design of appropriate IPR frameworks in a range of fields, from copyright to medicine and beyond are accompanied by the recognition that knowledge and technology do have a critical role to play in inclusive growth and development. This is consistent with the larger national interest being the raison d’etre for India’s reform of its IPR regime.

All this represents a very good beginning to the resolution of the bilateral stresses on IPR issues. But, it is important to remember that it is just a beginning. To the extent that the U.S. pre-summit position was influenced by claims from several businesses that their interests were being hurt, potential frictions have not yet been completely pushed aside. Businesses will obviously respond to specific actions by the Indian government, either positively or negatively. In the latter instance, pressure on the U.S. government to curb its enthusiasm will re-emerge. By the same token, on the Indian side, any perception amongst domestic interests that the reforms being proposed are being done to satisfy U.S. demands will provoke immediate resistance and potentially thwart change, particularly if it requires legislative action.

This is the complex and uncertain backdrop to the functioning of the high level working group. To have a chance of effectiveness, it needs to base its approach on three considerations.

First, India’s negotiating position must be based on a clear demonstration of protection and advancement of national interests, relating to both the innovation environment and the spread of benefits of technology.

Second, business interests on both sides need to be fully engaged in the process. They undoubtedly already are, but a continuous demonstration through the process that their interests are being helped or not being harmed will make the group’s functioning that much smoother.

Third, on the larger technology for development, the principle of “eminent domain” – which essentially allows the state to subordinate private property rights to the public interest in certain circumstances – must be given some space. In areas like health there is a welfare justification for making some options affordable, which would require capping the potential returns on IPR. Eminent domain is a well-established principle in U.S. jurisprudence. To the extent that it has a welfare-enhancing role in the IPR domain, the working group should explore it and seek to lay down some explicit boundaries.

To conclude, IPR is a domain that appears to have seen significant and positive movements from both India and the U.S. since the September 2014 summit. The considerations laid out above should enable the high level working group to reconcile both private and public interests in the two countries.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).