The CHIPS and Science Act has set the stage for a boom in U.S. semiconductor production. But a looming question threatens the development of the industry: Are there enough workers with sector-specific skills to support it? Currently, targeted educational programs are doing much of the heavy lifting to build the semiconductor workforce, but they will not be enough. Immigration reform, in particular, to expand the number of skilled-worker visas, is the only way to ensure that the CHIPS Act will achieve its full promise as a catalyst for U.S. high-tech manufacturing.

The U.S. has been losing market share in semiconductor manufacturing for decades. However, supply chain issues during the pandemic finally brought this trend to the fore, highlighting concerns about U.S. reliance on East Asian semiconductor chip manufacturers. This has led to a broad effort by the Biden administration to revitalize domestic manufacturing. One result is the bipartisan CHIPS act, which pledges a historic $280 billion toward expanding the domestic semiconductor industry, including $52.7 billion for semiconductor R&D, manufacturing, and workforce development; a $24 billion investment tax credit for semiconductor firms; and $174 billion to support R&D efforts across several U.S. agencies.

The good news is that private semiconductor firms have thus far been very responsive to these incentives—as of December 2022, more than 50 new semiconductor projects and $210 billion in private investment had been announced. Examples include Micron Technology, which announced a $100-billion investment to build a “megafab” (semiconductor manufacturing facility) in central New York, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), which announced that it would build a second fab in Arizona, where one is currently under construction, and increased its investment in the U.S. from $12 billion to $40 billion.

The bad news is that there are not enough workers to fill the expected number of jobs that these facilities will require. A joint report by the Semiconductor Industry Association and Oxford Economics projects that 85,000 new technical jobs (technicians, engineers, and computer scientists) will be created by 2030. But at current degree completion rates, 67,000 of these jobs—almost 80 percent—could go unfilled. These projections are not merely hypothetical: In July, TSMC announced that chip production in their new Arizona fab will be delayed due to a shortage of skilled workers.

Community colleges have the potential to prepare workers for the thousands of semi-skilled fab jobs that will be needed. In fact, several semiconductor degree and credential programs are now active. Unfortunately, there is a broad lack of awareness about—and among young people, a lack of interest in—semiconductor job opportunities. Young workers perceive manufacturing as an antiquated, dead-end career path, and semiconductor-related courses, credentials, and degree programs are experiencing significant under-enrollment across the country.

Similarly, there are simply not enough U.S. students pursuing STEM degrees to fill skilled positions in engineering and computer science. Compounding the problem is the myriad of job opportunities that STEM workers have outside of the semiconductor industry—for instance, at software companies like Meta, Google, and Amazon. In light of this, the Semiconductor Industry Association believes that “the workforce gap for individuals with advanced engineering and computer science degrees cannot be realistically addressed for the foreseeable future solely with U.S.-citizen graduates.”

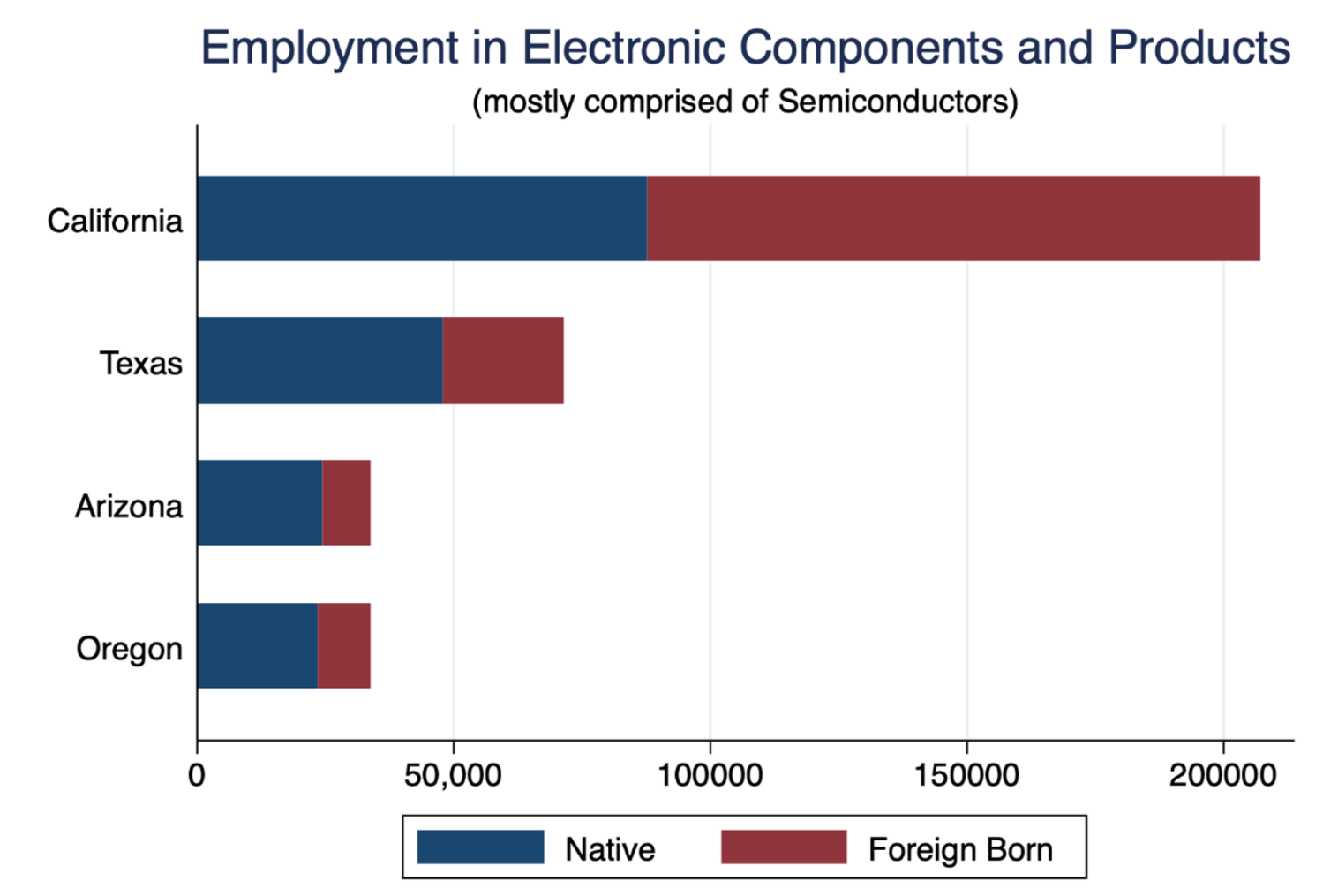

In other words, widening the semiconductor workforce pipeline will require immigration policy reforms that complement local skills building. The strongest evidence of this is the current workforce composition. The figure below depicts the semiconductor workforce in the four U.S. states that host the bulk of chip production, where we see that immigrants are essential. The sophistication of the chip fabrication process also means that many of these workers are highly specialized, such that a shortage of only a few key workers can hold up production.

One solution is to improve the retention of international graduates of U.S. universities. These graduates are generally eligible for the temporary H1B visa, but the number of H1B visas available each year is currently capped at 65,000, with an additional 20,000 available for advanced degree holders. This year the cap was reached at the end of February, reflecting the wide gap between the demand for, and supply of, these visas. The result is that an estimated 16,000 foreign-born engineers leave the U.S. every year, though most would like to stay.

A more permanent solution is to raise the cap on employment-based visas, which allow workers to eventually become lawful permanent residents (LPR). The annual ceiling on employment visas is currently fixed at 140,000 each year plus the number of unused family-sponsored preference visas from the previous year (a category that is also capped).

Beyond raising these caps, Congress should consider easing the burden of acquiring these visas in cases where there is a clear national interest in attracting skilled workers quickly—with the current semiconductor objectives being a perfect example. Specifically, employment-based visas require employers to demonstrate that the worker will not displace a qualified U.S. worker (known as the PERM process), which is lengthy and bureaucratic. One way of accelerating the hiring of skilled semiconductor workers would be to add semiconductor jobs to the “Schedule A” list of occupations. This list defines a narrow set of occupations for which the PERM process can be bypassed, saving firms and workers significant money and time.

Economic development policies are often enacted without sufficient workforce development strategies and the CHIPS Act is no exception. But it is still early days. And there are a range of simple policy tweaks and, admittedly less simple, workforce investment strategies that can ensure that the goal of reviving the U.S. semiconductor industry succeeds. Both local, sector-specific training, as well as targeted immigration reforms, will be required to make the most of this ambitious and potentially game-changing industrial policy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Industrial policy will require immigration reform

September 29, 2023