A recent TPC paper examined tradeoffs among revenues, progressivity and tax rates in tax reform. It concluded that, under certain assumptions, any revenue-neutral plan along the lines Governor Romney has outlined would reduce taxes for high-income households, thus requiring higher taxes on other, even if the plan’s financing is as progressive as possible, given the available tax expenditures. This paper addresses questions about that study and discusses new estimates that incorporate the taxation of municipal bond interest and the taxation of inside buildup in life insurance vehicles. These additions do not change the basic results.

Our recent paper[1] examined the tradeoffs among competing goals in tax reform – including maintaining tax revenues, maintaining progressivity, and lowering marginal tax rates. As a motivating example, we estimated the degree to which individual income tax expenditures would have to be limited to achieve revenue neutrality under the individual income tax rates and other features advanced in presidential candidate Mitt Romney’s tax proposals, and how the required reductions in tax breaks could change the distribution of the tax burden across households.

In this note, we summarize our earlier results and answer a number of substantive questions we have received about the study. We also discuss new estimates that incorporate into our analysis the taxation of interest income from municipal bonds and the taxation of inside buildup in life insurance vehicles.

I. Introduction

Our paper examined the effects of simultaneously pursuing five goals that Governor Romney has proposed:

- cut current marginal income tax rates by 20 percent,

- preserve and enhance incentives for saving and investment[2],

- eliminate the alternative minimum tax,

- eliminate the estate tax, and

- maintain revenue neutrality

We found that a tax reform plan that simultaneously met the first four goals would imply reduced tax burdens on families with income above $200,000. Meeting the fifth goal – revenue neutrality – would then imply increased tax burdens on other taxpayers, a necessary but perhaps unintended consequence. This was true even though we made the financing of the plan via tax expenditure reductions as progressive as possible by assuming that tax expenditures would be eliminated from the top down: first, we eliminated all available tax expenditures for those with income above $200,000; only if those revenues were insufficient to achieve revenue neutrality (which in fact they were) did we reduce tax expenditures for households with incomes below that level.

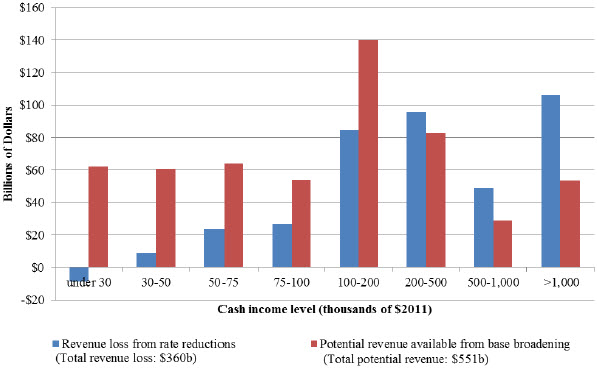

The basic logic of our central finding is captured in Figure 2 from our paper (attached here as well). The graph shows that cutting individual income tax rates by 20 percent from today’s levels would reduce tax burdens by $251 billion per year (in 2015) among households with income above $200,000. But, if we assume a strict interpretation of the second goal – preserving and enhancing incentives for saving and investment (see footnote 2) – there are only $165 billion of available tax expenditures to close in that group if tax rates are cut). As a result, to achieve revenue neutrality, the resulting $86 billion annual shortfall must be made up by raising taxes on the rest of the population.

We showed, in addition, that the same qualitative conclusions arise even when we added in feedback effects of tax changes on economic growth and revenues, using estimates of those effects that were developed by Harvard professor, and economic advisor to the Romney campaign, Greg Mankiw.

Figure 2. Revenue Reductions from Lower Rates and Revenues Available from Base Broadening

We show below, that the same qualitative results also hold if we eliminate exclusions for municipal bond income and inside build-up in life insurance, although doing so would decrease the net tax cut for high-income households.

We also emphasize that the various goals of tax reform are achievable, but there are tradeoffs among revenues, lower tax rates, and progressivity.[3] For example, if Governor Romney eventually specifies a full tax reform proposal that is not revenue-neutral and/or that raises taxes on some forms of saving and investment, there is no a priori reason why that full-reform proposal would have to raise taxes on middle-class households. Nevertheless, it remains true – as we showed in our paper – that a reform proposal that meets the five goals stated above would have to raise burdens on middle-class households.

II. FAQs

Q: How can you analyze Governor Romney’s proposals when there is no fully-specified Romney tax plan?

A: We acknowledge upfront, here and in the earlier paper, that Governor Romney has not fully specified his tax plan. But it is still possible to examine the broad implications of the five goals noted above, which derive from information he and his campaign have made available. We analyzed the implications of those five goals; we chose the most progressive route for financing his stated choices, given how much revenue can be raised by broadening the tax base that is available after accepting the five goals.

Q: Did you say that Governor Romney wants to raise taxes on the middle-class?

A: No. We said that simultaneously achieving all five of the tax goals stated above would result in lower taxes for high-income households and thus – because of the revenue-neutrality constraint – would require raising taxes on other households.

Q: Did you say that revenue-neutral, distributionally-neutral tax reform is mathematically impossible?

A: No. We said that revenue-neutral, distributionally-neutral tax reform was mathematically impossible under the five goals listed above. It is, of course, possible to achieve revenue-neutral, distributionally-neutral tax reform, but that would require giving up one or more of the five goals. We discuss differences between the Romney proposals on the one hand and the Tax Reform Act of 1986 and the Bowles-Simpson proposals below. For instance, one key difference between the Romney proposals and the two broad-based reform proposals is that under TRA 86 and the Bowles-Simpson plan capital gains and dividends are taxed as ordinary income.

Q: Are the assumptions you chose for how to reduce tax expenditures across income groups politically and administratively realistic?

A: We eliminate tax expenditures “from the top down,” first taking away all benefits from high-income households and then paring back benefits for other households only if necessary to meet revenue targets. As a result, our analysis assumes that if a family’s income rises from $200,000 to $200,001, it would lose all of its available tax expenditures. As we discuss in the paper, this would be difficult to administer, but it would make the financing as progressive as possible.

The key point is this: The logical implication of our “most progressive, but politically and administratively unrealistic” approach is that any form of financing that is politically and administratively realistic would be less progressive than the plan we have estimated, given the other aspects of the Romney proposals. Any more realistic approach would require greater middle-class tax increases and larger high-income tax cuts.

We are not saying that the most likely way that tax expenditures would be reduced in the real world would be “from the top down.” Instead, we show that even if tax expenditures were reduced in that most progressive manner, the Romney proposals as a whole imply a shift toward a less progressive tax system.

Q: How did you choose which deductions and loopholes to close and which ones not to close?

A: The paper’s Appendix lists the tax expenditures we considered in our analysis. Similar to Nguyen, Nunns, Toder, and Williams (2012)[4], we divided tax preferences into groups: (1) exclusions of income from sources that are administratively difficult to tax (such as imputed rent from owner-occupied housing or other minor items); (2) tax preferences for savings and investment; and (3) all other tax expenditures (which are “on the table” for reduction in the exercise we pursue.)

We did not close tax preferences for savings and investment based on statements and literature from the governor and his campaign. For example, the second of the four key planks in his economic plan is “reduce taxes on saving and investment.”[5]

Q: How did you treat Governor Romney’s corporate reform proposals, which included a reduction in the corporate tax rate to 25 percent?

A: The plan released by Governor Romney earlier this year proposed to reduce the corporate tax rate to 25 percent, make the research and experimentation credit permanent, extend full expensing of capital expenditures for one year, and provide a tax holiday for repatriation of corporate profits held overseas. None of these changes would be paid for by offsetting reductions in tax preferences.

Governor Romney’s tax advisors told TPC that the (then, as now, unspecified) cuts in corporate tax preferences were not meant to finance the initial rate cut to 25 percent but instead would pay for a subsequent revenue-neutral set of proposals that would reduce corporate rates further and enact a territorial system.

In our analysis, we assumed that Romney’s plan to reduce the rate to 25 percent could be achieved through some unspecified corporate base broadening, and therefore that the revenue and distributional consequences of this rate cut could be ignored in the remainder of our analysis. If, instead, we had included the reduction in the corporate tax rate (which would reduce revenues by $96 billion in 2015 in the absence of base-broadening), the result would have been an even larger tax cut on high-income individuals, requiring even larger cuts to tax expenditures, and correspondingly larger increases in taxes on middle- and/or lower-income taxpayers.

Q: Why do you assume revenue neutrality?

A: Our analysis assumed that the Governor’s tax reform would be revenue-neutral based on published statements from Governor Romney’s economic advisors. Most recently in an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal, Glenn Hubbard confirmed that the Romney plan “would broaden the tax base to ensure that tax reform is revenue-neutral.”[6] Similarly, Gregory Mankiw in an NPR interview said that tax reform “would be revenue neutral by broadening the base and lowering the rates.”[7] Finally, the white paper from the campaign’s chief economic advisors (Glenn Hubbard, Gregory Mankiw, John Taylor, and Kevin Hassett) says that tax reform is one of the Governor’s four main economic pillars. In addition to lowering tax rates, it would “broaden the base to ensure that tax reform is revenue-neutral.”[8]

Q: Why didn’t you include the effects of proposed spending cuts?

A: We focus on the tax proposals put forth by Governor Romney. Because he has asserted that the proposed tax changes would be revenue-neutral, we can assess their distributional effects without referring to spending changes. It is worth noting, however, that government spending tends to help low- and middle-income households, and a large-scale reduction in government spending would likely be significantly more regressive than reductions in tax expenditure.[9]

Q: How does your analysis deal with potential economic growth effects of the tax proposals?

Estimates from the Congressional Budget Office and other sources indicate that the effects of tax cuts on the macroeconomy are likely to be small or even negative over the typical 10-year budget window, depending in part on how they are financed.[10]

In revenue-neutral tax changes, the tax rate reductions can raise incentives to work, but the base-broadening measures increase the portion of Americans’ income that is subject to tax, and create incentives that would work in the other direction. At the end of the day, the net effects are likely to be small (Auerbach and Slemrod 1997[11], Brill and Viard 2011[12]). A 2007 Treasury report that analyzed the effects of business tax changes on business competitiveness concluded the following: “Indeed, the Treasury Department estimates that the combined policy of base broadening and lowering the business tax rate to 28 percent might well have little or no effect on the level of real output in the long run because the economic gain from the lower corporate tax rate may well be largely offset by the economic cost of eliminating accelerated depreciation” (p. 48). [13]

Nevertheless, as we discuss in the paper, our results are not qualitatively different, even if we include additional taxes generated from the growth effects implied by the rule of thumb estimates from Mankiw and Weinzierl (2006).

Q: How do Governor Romney’s proposals differ from the Bowles-Simpson plan, which also included a 28 percent top marginal tax rate?

A: The principal difference between the Bowles-Simpson tax framework and the five goals noted above is the treatment of taxes on saving and investment. The Bowles-Simpson framework would tax capital income from almost all sources at the same rate as ordinary income. Specifically, the plan would eliminate the preferential rates on capital gains and dividends, impose tighter caps on retirement account contributions, and eliminate the exclusion of capital gains taxes on principal residences and other common tax breaks that encourage savings and investment. In addition, the Bowles-Simpson framework would eliminate the step-up in basis at death and retain the estate tax. These provisions would raise large amounts of revenues, particularly from high-income taxpayers, and are essential in facilitating the reduction in top tax rates while maintaining progressivity.

In contrast, the Romney campaign has called for “further reductions in taxes on savings and investment” and specifically calls for the elimination of the estate tax, retaining preferential rates on capital gains and dividends, and lowering tax rates on capital gains, dividends, and interest to zero for most taxpayers.[14]

Q: How are Governor Romney’s proposals different from the Tax Reform Act of 1986?

A: The Tax Reform Act of 1986 raised corporate tax revenues, taxed capital income at ordinary income tax rates, restricted deductible IRA contributions, and eliminated many tax shelters that disproportionately benefited high-income groups. Governor Romney’s plan would reduce corporate taxes and maintain preferential rates on capital gains and dividends, among other things.

Q: What if some preferences for saving and investment were curtailed and/or taxes on capital income were raised?

A: As we have discussed, tax reform requires trade-offs and not all goals can be met simultaneously. In our paper, as in previous TPC analysis of base-broadening reforms, we did not consider increases on taxes on the return to saving or investment as a way of financing the tax cuts.

Some commentators have questioned that decision and suggested that some incentives for saving and investment—in particular, the exclusion of interest on state and local bonds and the exclusion of inside-buildup on life insurance vehicles—are in fact “on the table” as far as Governor Romney is concerned, as a way of financing the tax cuts. (Note, though, that “on the table” does not necessarily mean “in the plan.”)

In addition, some commentators have suggested that eliminating the two exclusions could go a long way towards offsetting the net tax cut for high-income households and the net tax increase for everyone else. In particular, a thoughtful and constructive blog post by Matt Jensen at AEI in response to our study has suggested that upwards of $90 billion could be raised through closing these two exclusions.[15]

With these issues in mind, we estimate here the potential effects of eliminating the two exclusions. We conclude that there is much less revenue than $90 billion available from these two tax expenditures. Although completely eliminating the exclusions would reduce the net tax cut for high-income individuals, our main result still holds.

There are two reasons why the available revenue is substantially less than $90 billion. First, Jensen combines the corporate and individual tax expenditures of the cost of these provisions. For example, according to the Budget of the U.S. Government for the 2013 Fiscal Year, the total tax expenditure for the exclusion of interest on state and local bonds is $63.8 billion in 2015.[16] However, about $18.6 billion accrues to corporations, and we have already treated this portion as eliminated to pay for corporate tax reform.

Second, the government’s tax expenditure estimates are based on current law that includes a scheduled top rate of 39.6 percent and the 3.8 percent surtax enacted in the Affordable Care Act. Thus, although the Budget shows $45.2 (=$63.8-$18.6) billion in individual income tax expenditures for exclusion of interest from state and local bonds, the revenue gain under Governor Romney’s proposals would be substantially smaller than the budget document suggests because tax rates under his plan would be substantially lower (starting from the lower current-policy tax rates and including a 20 percent reduction on taxes on interest for high-income taxpayers and tax exemption on all interest income for low- and middle-income taxpayers). The lower tax rates significantly reduce the value of the tax exemption (Nguyen et al (2012) explore this connection in detail). Using the TPC model, we estimate that under the Romney proposals eliminating the exclusion of state and local bond income would raise $28.7 billion in 2015. However, not all of this revenue would be raised from high-income taxpayers—about 15 percent would come from taxpayers earning less than $200,000. Hence, only about $25 billion would be available to offset the $86 billion net tax increase for taxpayers making less than $200,000—far below the $63.8 billion tax expenditure reported in the Budget.

Similar issues hold for the taxation of inside-buildup on life insurance savings. The Treasury estimate of the individual income tax expenditure in 2015 is $25.4 billion based on current law. Although we have not estimated the effects of changing this provision within the TPC tax model, the maximum revenue that could be obtained under Governor Romney’s plan would be between 65 and 80 percent of that figure (or between $13 and $20 billion), because of the lower tax rates he proposes.[17]

Thus, eliminating these two exclusions would raise no more than $49 billion ($28.7 billion plus $20 billion). Moreover, at least $4 billion would come from families with income under $200,000. While this would go some way towards offsetting the $86 billion on net tax cuts for higher-income taxpayers, it does not eliminate the gap. And, of course, doing so would be difficult politically and practically.

Adding these two provisions to Governor Romney’s list of tax preferences potentially on the chopping block would thus not reverse the basic conclusion of our paper: simultaneously pursuing the five goals noted above would make the tax system less progressive, even if the tax expenditures used to finance the proposals are reduced in the most progressive way possible.

[1] https://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2012/08/01-tax-reform-brown-gale-looney

[2] Governor Romney has explicitly promised to retain current preferences for dividends and capital gains. The claim of preserving and enhancing incentives for savings and investment is a less explicit policy goal and is therefore open to interpretation. It could mean to preserve every incentive for savings and investment or it could mean on net to preserve broad incentives while leaving open the possibility of eliminating more targeted incentives. In our original paper, based on the Governor’s statements, we employed the first interpretation and did not close any tax subsidies affecting savings and investment. In this note, we examine the effects of eliminating the tax incentives for two explicit saving vehicles—municipal bonds and insurance policies.

[3] For more discussion on this and other issues, see Donald Marron’s blog post on the TPC website: http://taxvox.taxpolicycenter.org/2012/08/08/understanding-tpcs-analysis-of-governor-romneys-tax-plan/

[4] http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/url.cfm?ID=412608

[5] http://www.mittromney.com/sites/default/files/shared/TaxPolicy.pdf

[6] http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390443687504577562842656362660.html

[7] http://www.npr.org/2012/08/05/158156529/a-peek-into-the-republican-economic-tool-kit

[8] http://economistsforromney.com/2012/08/12/the-romney-program-for-economic-recovery-growth-and-jobs/

[9] For example, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has analyzed the spending framework produced by the Romney campaign and concluded that with overall spending capped at 20 percent of GDP and maintained preference for defense spending, the result would be significant cuts in programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3658

[10] See, for example the CBO analysis of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/44xx/doc4454/07-28-presidentsbudget.pdf

[11] http://ideas.repec.org/a/aea/jeclit/v35y1997i2p589-632.html

[12] http://www.aei.org/files/2011/09/27/TPO-Sept-2011.pdf

[13] http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Documents/Approaches-to-Improve-Business-Tax-Competitiveness-12-20-2007.pdf

[14] For more discussion on the difference between these plans, see Howard Gleckman’s blog post on the TPC website: http://taxvox.taxpolicycenter.org/2012/08/09/the-bowles-simpson-and-romney-tax-plans-have-almost-nothing-in-common/

[15] http://www.aei-ideas.org/2012/08/how-the-tax-policy-center-could-improve-their-romney-tax-study/

[16] http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2013/assets/receipts.pdf

[17] For example, the top rate under Romney’s proposals would be 28 percent, which is about 65 percent of the top rate under Obama’s proposals (39.6 percent plus the 3.8 percent ACA surtax). So, if all of the holders inside build-up in life insurance faced the top rate, the tax expenditure would be 65 percent as large under Romney’s plan compared to current law.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).