Editor’s Note: On May 27, 2009, Russia announced its intention to buy up to $10 billion of the International Monetary Fund’s first-ever bond sale. Russia’s announcement makes good on its April G-20 Summit pledge to purchase bonds to help bolster the IMF’s resources in order to aid countries suffering from the global financial crisis. China, India, Brazil and other emerging economic powers are expected to announce similar purchases soon. In the following article from early May 2009, Eswar Prasad discusses how the bonds might be structured, and implications for the U.S. and global economy.

At their meeting in April 2009, the G-20 leaders committed to increasing the IMF’s resource base by $500 billion. This increase was to take place through an expansion of the New Arrangements to Borrow—a credit line provided to the IMF by a small group of its member countries. Commitments for only $325 billion have been received so far, including a $100 billion U.S. commitment that still needs Congressional approval.[1]

No emerging market has announced a contribution yet, although many of them have enormous stocks of foreign exchange reserves. These countries have sought instruments that would allow them to make a temporary contribution to the IMF’s resource pool, deferring permanent contributions or commitments until they see real progress on governance reforms at the IMF that would give them larger voting shares.

The IMF is therefore considering issuing bonds that would help emerging markets make contributions in a manner that these countries deem acceptable. This note provides some background information on such bonds and discusses the implications of the IMF having access to this new source of financing for its operations. Depending on how they are structured, these bonds could prove attractive to emerging markets by giving them a tool for diversifying the currency composition of their foreign exchange reserves. This could have some implications for the demand for U.S. treasuries, possibly pushing up U.S. interest rates modestly.

How Would the Bonds Be Structured?

The IMF already has in place a framework for issuing bonds. This framework was approved in the early 1980s but has never been used. The proposal to issue bonds was revived about a year ago when the IMF was facing cash flow difficulties in financing its administrative operations. This proposal has now resurfaced as a vehicle for increasing the IMF’s resource base.

A number of details regarding the structure of the bonds are being worked out by the IMF. But some details can be gleaned from existing proposals. These bonds would be traded only amongst the IMF and official agencies, i.e., central banks of the IMF’s member countries. There would be no secondary market for private investors to acquire or trade these instruments.

It is likely that the bonds would be denominated in SDRs and pay an interest rate linked to the SDR interest rate. The SDR is the IMF’s composite unit of account that is comprised of four major freely convertible currencies with the following weights: US dollars: 44 percent; euros: 34 percent; yen: 11 percent; and pound sterling: 11 percent. It is expected that the maturity of these bonds would be relatively short, perhaps around 12-18 months.

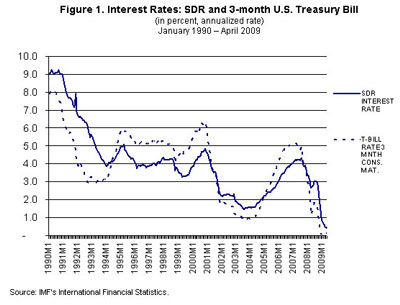

Figure 1 shows that the SDR interest rate at short maturities is not systematically higher or lower than the U.S. Treasury bill rate, although the two often diverge from each other for extended periods. At present, the SDR interest rate is higher than the U.S. 3-month t-bill rate by about 30 basis points (0.42 percent vs. 0.15 percent, at annual rates).

Figure 2 shows that the exchange rate between the SDR and the U.S. dollar has fluctuated considerably over the last two decades, reflecting the U.S. dollar’s fluctuations against the other major currencies. Clearly, an SDR-denominated bond would allow a country to diversify the currency composition of its foreign exchange reserves.

The bond issuance could take one of two forms. It could be an upfront placement of bonds by the IMF to augment its tangible pool of resources. Or it could be a commitment by a country to buy a certain amount of IMF bonds should there be a need for the resources. The NAB and the recent bilateral loans offered by various countries are both contingent commitments. Even such contingent commitments do have potential budgetary implications at the national level.

Is there a precedent among other international financial institutions for issuing such bonds? The World Bank already issues bonds, raising about $30-35 billion worth of financing each year through these instruments. These bonds, with maturities of up to one year, can be traded among official agencies as well as private investors and carry a market-determined rate of interest. They can generally be counted as foreign exchange reserves as they carry a triple-A rating, are liquid and denominated in convertible currencies.

Would Emerging Markets Bite?

For emerging markets, IMF bonds have many attractive features. First, they would count as foreign exchange reserves per the IMF’s definition. This implies that emerging markets could simply substitute one reserve asset for another by buying these bonds. Second, buying these bonds using existing foreign exchange reserves would have no budgetary implications and would not require legislative approval. Third, IMF bonds would facilitate diversification in the currency composition of reserve holdings. The value of SDRs is based on four currencies, with the U.S. dollar accounting for only 44 percent of the total weight, as noted earlier. The SDR interest rate is also slightly higher now than the yield on U.S. treasury bills.[2] Fourth, the emerging markets would be able to restrict their additional financial support for the IMF to a limited period rather than an open-ended commitment via the NAB. This would enable them to maintain pressure for eventual reforms that would give them greater representation at the IMF in exchange for providing more permanent contributions.

Loan commitments with a limited tenure would have some similar properties except that there could be direct budgetary implications. Loans to the IMF, unlike bonds, could not be counted as international reserves as they would not be liquid or easily convertible into hard currencies. They would of course increase a country’s borrowing capacity from the IMF, but such borrowing could be subject to conditionality.

Official statements and off-the-record comments by officials from the BRIC emerging markets suggest that many of their central banks might just switch out of U.S. treasuries and into IMF bonds if those bonds became available. In this manner, these countries could achieve multiple ends, both substantive and symbolic, with existing resources.

A Win-Win Proposition? Almost, but Not Quite

The implications of bond financing for the IMF differ across country groups. With its expanded resources, the IMF would have more money to forestall or deal with crises in Eastern European economies. But Europe would be able to maintain its go-slow position on IMF governance reforms. Thus, the European Union would get more IMF support for countries in its backyard and also for some of its own weaker members, without giving up any of its influence at the Fund. Still, a temporary augmentation of the IMF’s resources through bonds rather than a direct and permanent NAB expansion would at least keep symbolic pressure on Europe to support substantive governance reforms.

China would also have it both ways. China could continue its policy of maintaining an undervalued exchange rate but would now have an alternative to U.S. government bonds for parking the foreign exchange reserves it accumulates through intervention in the currency market. If the issuance of IMF bonds and the diversification possibilities it offers led to a depreciation of the U.S. dollar against other major currencies, the Chinese would still do fine if they kept the renminbi’s value stable relative to the dollar. SDR-denominated bonds could also indirectly bolster China’s case for making the SDR an international reserve currency.

Many of the weaker emerging markets that do not have large stocks of foreign exchange reserves and have been hit hard by the crisis would benefit from the IMF’s larger resource base. So would low income countries that the IMF is supporting as they deal with balance of payments problems.

The U.S. would also benefit significantly from greater international macroeconomic and financial stability. Nevertheless, the U.S. could face a small short-term cost if there were to be a decline in the demand for its government bonds. This could be perilous at a time when the government’s financing needs are rising rapidly and markets are nervous about massive deficits and future inflationary risks. A switch out of U.S. Treasuries could push up short- and long-term U.S. interest rates and increase the cost of servicing U.S. government debt.

How significant is this concern? In 2008, the increase in net government debt was $1.2 trillion; about $77 billion (or 6 percent) of that was financed by foreign governments’ purchases of U.S. treasury bills and bonds. In 2009, the larger U.S. budget deficit could imply a financing need of nearly $2 trillion. If some key emerging markets decided to sell about $150 billion of their U.S. government securities in order to buy IMF bonds, that could lead to a significant decline in the prices of those securities. In other words, U.S. interest rates would rise.

This is likely to be tempered by two factors. First, if the bonds were in the form of contingent commitments, there would be no immediate need for emerging markets to switch out of U.S. treasuries. Second, even if the bonds were sold upfront, the IMF would presumably need to maintain 44 percent of the total amount in U.S. treasuries in order to mimic the SDR basket and avoid any capital loss (in SDR terms) on the bonds. On the other hand, a serious concern is that the prospect of China and other emerging markets having another alternative to U.S. treasuries could act as a trigger for an adverse market reaction to broader concerns about rising U.S. debt.

To summarize, it is a matter of common interest for the IMF to have enough resources to bail out a number of middle- and low-income countries that are at the brink of collapse as the aftershocks of the crisis hit them. While there are broad benefits to the world economy, the short-run costs of boosting the IMF’s resources via bond financing may be borne disproportionately by the U.S.

IMF Governance Reforms

The U.S. has come out strongly in favor of fundamental reforms to the governance structure of the IMF, especially to give the major emerging markets a bigger role in the institution’s voting structure. However, statements by European Executive Directors at the recent IMF-World Bank Spring Meetings suggest that European countries, especially the smaller ones in continental Europe that have the most to lose (such as Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden), are digging in their heels to prevent significant reapportionment of voting shares at the IMF. They have grudgingly agreed to move up the next round of changes in voting shares–the “quota review” that was set for 2013–to 2011.[3] Those changes are glacial in pace and, in any event, represent decimal-point reforms rather than the more fundamental reforms that the institution needs in order to gain legitimacy in the eyes of the systemically important emerging market countries.

At this time of crisis, the international community might actually have leverage over the Europeans. They are keen to rapidly augment the IMF’s resource base to ensure that it will have enough fire-fighting capability to douse the fires that are breaking out in Eastern Europe and that could also singe eurozone economies such as Greece and Ireland. The U.S. and major emerging markets should use this opportunity to push hard against further intransigence from continental Europe on IMF reforms.

Bottom Line

IMF bonds could be a quick and effective approach to expand the institution’s resource base at a time when the world economy is no longer at the edge of the abyss but faces a rocky road to recovery and stability, with many economies still vulnerable to the aftershocks of the crisis. There are many side benefits for certain groups of countries, especially the emerging markets, to using this approach. But the way it is implemented could bump up U.S. interest rates modestly.

By delinking the resource and governance issues, IMF bonds provide a politically palatable route for many countries to provide temporary support for the IMF without tackling any of the difficult challenges on reforming the structure of the institution. Unfortunately, adopting this quick fix rather than forging a tough compromise in the cauldron of this crisis would truly be a big lost opportunity for more fundamental reforms.

Raising the IMF’s permanent resource base through a general increase in quotas would be a cleaner approach, although politically much more complicated. A quota-based increase in the NAB, as proposed by the key emerging market economies, would be a reasonable compromise. This would tie together a significant permanent increase in resources with changes in the structure of voting rights. The IMF needs more than just resources to become a credible and effective multilateral institution.

[1] Japan and the European Union have agreed to loan $100 billion each to the IMF. Canada and Switzerland have pledged $10 billion each while Norway has committed to $4.5 billion. These contributions could be rolled over into the NAB.

[2] The short-term SDR interest rate is of course lower than the rate on longer-maturity U.S. government bonds. Since mid-2008, however, China and other emerging markets appear to have shifted towards large net purchases of short-term treasury bills rather than longer maturity treasury bonds.

[3] The March 2009 Report of the Committee on IMF Governance Reforms (chaired by Trevor Manuel) recommends that this quota review should be concluded by mid-2010, followed immediately by a commencement of the next review.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

IMF Bonds: Details and Implications

May 4, 2009