Studies in this week’s Hutchins Roundup find that a significant percentage of the elderly with long-term care insurance end up on Medicaid, falling oil prices and dollar appreciation affect core inflation, and more.

Even those holding long-term care insurance may end up on Medicaid

Margherita Borella of Università di Torino, Mariacristina De Nardi of Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, and Eric French of University College London use the Health and Retirement Survey data to analyze who receives Medicaid in old age and why. They find that, even though Medicaid is a program intended for “poor” households, a significant fraction of people with high lifetime income and even some people with long-term care insurance end up on Medicaid at very old ages. Specifically, among the singles aged 95 and older in the top permanent income tercile the Medicaid recipiency rate is between 5% and 10% and for the whole sample the probability of being on Medicaid conditional on holding long-term care insurance is 5.8%.

Energy and import prices affect core, long-run inflation with a one-year lag

Andrew Lee Smith of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City explores the cumulative effects of oil prices and the foreign-exchange value of the U.S. dollar on the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation. He estimates that movements in oil prices and the appreciation of the dollar have their peak effect on core PCE inflation after 12 to 15 months, suggesting that inflation may not return to the 2 percent target until 2017. Return to that target would be further delayed, if oil prices continue to decline or the foreign-exchange value of the dollar continues to appreciate he notes.

Only large exchange rate changes pass through significantly to import prices

John Lewis of the Bank of England reconciles a puzzle in trade data: Why do micro studies of particular firms or product lines find that changes in exchange rates pass through much less into import prices than do macro studies of aggregate exchange rate changes? Using 1990-2012 data for the UK and 45 trading partners, he shows that this is because exchange rates and pass through aren’t linearly related—When bilateral exchange rates change less than 5% in a year, only 16% of the change is reflected in import prices, but when they change over 5% in a year, 75% passes through. Since aggregate changes in exchange rate indexes are driven primarily by large swings, macro estimates are much closer to the 75% range.

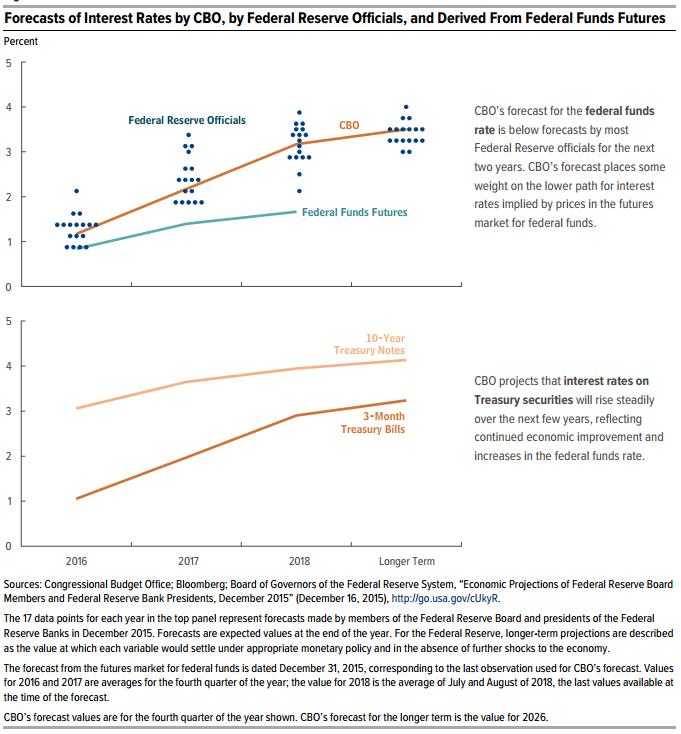

Chart of the week: CBO’s forecast for the federal funds rate is below forecasts by most Fed officials

Quote of the week: “

The risks are currently falling

,” says European Central Bank’s Mario Draghi

[W]hat matters for the health of banks is not the level of interest rates, but the quality of supervision… [B]anks are actually stronger now than they were a few years ago. Capital ratios for euro area banks have risen from around 8% in 2007 to close to 14% today. In other words, the risks are currently falling, not rising.

What’s more, though low interest rates can encourage risk-taking, there are no warning signs of serious financial instability. Financial crises are typically associated with strong credit growth and rising leverage in the banking system. What we see at the moment, however, is a nascent credit recovery and deleveraging among banks. In fact, coming out of a deep banking crisis, rapid credit growth would really be a “luxury problem”!

–-Mario Draghi, President of the European Central Bank

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Hutchins Roundup: Elderly Medicaid recipients, inflation, exchange rate pass through, and more

January 28, 2016